The Parsi

Kersi Rustomji’s fantastic visual effects in introduction to East Africa, for those who really want to know and it is a subtle way and an insight into educational introduction and a door way to knowing more about the East African Asian.

Where Did You....zip

Compressed archive in ZIP format [10.2 MB]

Kersi Rustomji (Blog below)

A Parsi or Parsee /ˈpɑrsiː/ is an ethnic Persian member of Zoroastrian communities in India. They are legally and ethnically distinct from the Iranis even though both groups are Persian Zoroastrians.

According to the Qissa-i Sanjan tradition, the present-day Parsis descend from a group of Zoroastrians from Greater Iran who immigrated to Gujarat in western India during the 8th or 10th century[3] to avoid persecution by Muslim invaders who were in the process of conquering Iran.[4][5][6][7][8][9] At the time of the Muslim conquest of Persia, the dominant religion of the region was Zoroastrianism. Iranians rebelled against Arab invaders for almost 200 years; in Iran this period is now known as the "Two Centuries of Silence" or "Period of Silence".[10] During this time many Iranians who are now called Parsi rejected both options and instead chose to take refuge by fleeing from Iran to India.[11]

Cont:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parsi

Kersi's Opus

Introduction

Kenya Asians and the Parsis

Indian merchant mariners, Arab seafarers, Chinese and Persian sailors, among other seafarers have all

visited the East African coastline stretching from the Horn of Africa to the port of Sofala in the south.

From the times of the Egyptian Pharaohs who hired Phoenician mariners to the pre-biblical era and after,

these visitors came to trade on the African coast.

Although historians have not widely highlighted these visitors and the flourishing trade, its extensive

evidence found on the East African Coast, known as Zeng or Zenj as well as Azania, deep inland, and as far south as the ruins in Zimbabwe, is highly indicative of commerce long time before its

colonial occupation.

The presence of Indians in East Africa is well documented in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea or Guidebook

of Red Sea by an ancient Greek author written in 60 AD. The ancient Indian work the Puranas also mention the East African coast as well interior of Kenya as far as Lake Victoria, which was known as ’

Nil (Nile?) Sarover,’ Lake Nil, and knew the source the of ‘Nil’ Nile.

The Indian sea merchants from the Gulf of Kutch and further south on the west coast of India sailed their

seagoing dhows, large wooden ships with a huge lateen sails, aided by the alternating monsoon winds. The North East monsoon winds brought these merchant sailors across the Indian Ocean to the African

east coast from December to March. After trading and bartering, they returned using the reversed South West winds from June to September.

They sailed regularly to the Zenj Coast where they traded in cloth, metal implements, iron nails, copper

wire, glassware, wheat, rice, sesame oil, raw sugar, and salt.

On their return trip, they carried incense, palm oil, myrrh, gold, copper, spices, ivory, rhino horn, wild

animal skins and ‘boriti’, mangrove poles. As time went by, some Indians settled on the East African coast and set up their shops to trade in the merchandise from the dhows. These were the pioneer

Indian traders on the East African coast. They were exclusively traders, and not indentured workers.

The Indians have had ancient connections not just with the East African coastline but also its hinterland.

The more intrepid Indian ‘nakhoda,’ skippers, undertook caravans on foot safaris to the interior. They knew of places as far inland as Uganda. They also knew the Ruwenzori Mountains as ‘Chandragiri

Shekhar,’ Moon Mountain or Mountains of the Moon.

They had knowledge of the great inland lake, the ‘Neel Sarover’ Neel (Nile?) Lake, named much later as

Victoria Nyanza, and even of its outlet the source of the Nile.

Much later European explorers encountered Indians settled in the interior married to the indigenous

women.

Relics of Chinese pottery found in the ruins along the Kenya coast at Gedi and Bagamoyo in Tanganyika, now

Tanzania, indicates that the Indian merchant sailors who traded with China, in turn traded with the Gulf Arabs who then transshipped this cargo to the East African coast. These relics found in the

great ruins of Zimbabwe, also indicates that the Indian trade connection was an old thread in the history of the region.

From the second to the eighth century, no major changes took place on the coast. However, with the rise of

Islam, the Omani Arab rulers who came to the East African Coast, turned the coastal settlements into city-states with the most important one being Zanzibar followed by Mombasa, Pate, Malindi, Manda,

Tanga, and Kilifi. Using local stone and coral, they built palaces, houses, and mosques to give Islamic atmosphere and culture to the coast, which endures to this day. The Indians traded along with

the Arab traders in these city-states that flourished undisturbed until the arrival of the Portuguese seafarer Vasco da Gama.

Cont:

http://zoroastrians.net/2011/05/16/kersi-rustomji-parsi-of-kenya

FOR MY PEOPLE THE PARSI

By Kersi Rustomji

44 Zamani

During the old days, zamani, in granny’s time and till the Kilindini harbour was built in the west, the Old Port was a very busy place, as all the steamers from the U. K. Europe, India and the Far East berthed here. In fact, it was here that she too had landed when she arrived in Kenya with her stepmother to join her dad in Nairobi, in 1898.

Cont: http://kersi.50webs.com/index.html

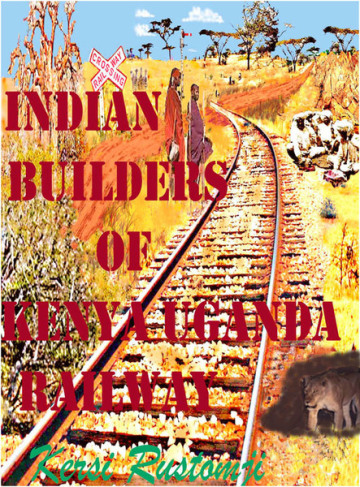

Kersi Rustomji is currently revising his autobiography, a major undertaking, and a continuing work on the Indian Railway Builders of Kenya Uganda Railway. Please see the attached cover and thanks again to Kersi for sharing all this with us.

The Cover

Commencing from the bottom, the cover depicts on the left, the thick thorny scrub and a baobab tree of the semi-arid terrain past the green lush coastal plain from Mombasa. The scrub with long sharp thorns was hacked by hand to clear the bed for the sleepers and the rails. The bed also cleared by hand using, picks, shovels, and other hand tools. After the sleepers were set on the rail bed, the rails too were attached, again using hand tools only.

Similarly, the stone for ballast between the sleepers to keep the dust down, was broken by hand from the quarry using hammers and chisels, and carried on heads in a karai, an iron basin. Larger stone blocks for construction of bridged were similarly hewn from quarries.

The line swings past the scrub and heads past a signal towards the next the station to be built. A kuchaa, not tarred, red murram road, sweeps past the baobab, across the rails and disappears into the savannahs, scattered with the flat-topped thorn acacias, against bright African sky. A typical level crossing sign indicates the approach of the railway tracks.

Beyond the level crossing signs some zebras gaze at the two Masai morans, warriors, who are looking at the Indian stonemasons across the lines. The masons are breaking the rocks from the quarry behind them into stones for the ballast also done with hammers and chisels.

Below the stonemasons in the right hand corner is a mane less lion, a reminder of the killings by the man-eaters of Tsavo, which killed a number of rail builders.

The text is in the Kenya Uganda Railway livery of the dark plumb red of the coaches and the locomotives. The green of the signature is the green of the line clear signal.

Cover design and graphic © Kersi Rustomji 2014

prema, shanti,ahinsa.

upendo,raha, latifu...

love,peace,kindness...

Only One Human Race...

Kersi Rustomji.Planet Earth. ex-Kenya. Australia.

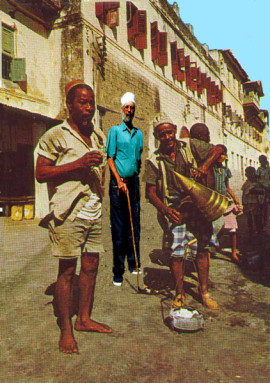

A Zoroastrian in Zanzibar

Click on Photo

Posted July 22, 2012 by Farah Bala

If you are familiar with the Zoroastrian community, you probably know that it is one whose numbers are dwindling very rapidly with an approximate world population of 300,000, including both the Iranian and Parsi Zoroastrians. When 2 Zoroastrians meet for the first time, there is an instant sense of familiarity followed by a barrage of questions inquiring about families, home towns, ancestry and a whole lot more. Yes, I am a Parsi Zoroastrian.

During my conversations with the locals when I heard, first of a likelihood, and then a definitive assurance, that there was indeed a Parsi family still living in Zanzibar, there was no way I was leaving the Island without meeting them. Finding out where they lived wasn’t as difficult as I would have thought. Just then, Amanda told me she had read an article not too long ago of the existence of an Agiary (Parsi Temple) in Zanzibar, relatively close to Stone Town.

I was now on a mission! However, not too many people knew about this temple. Although there was a thriving Zoroastrian community in Zanzibar for hundreds of years, a majority of them had left during the revolution. Those who stayed on had slowly passed away. We tried to find the woman who had written the article on the internet, but to no avail.

Cont:

http://farahbala.wordpress.com/2012/07/22/a-zoroastrian-in-zanzibar/

FIRST STEPS – CHILDHOOD IN ZANZIBAR

http://www.mercury-and-queen.com/zanzibar.htm

Book: Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism

Mary Boyce

http://www.amazon.ca/Textual-Sources-Study-Zoroastrianism-Boyce/dp/0226069303