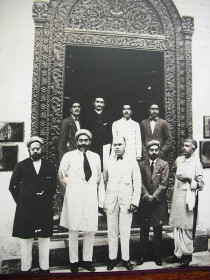

Legacy of Colonialism, Tyranny of African Nationalism Viewing Asian African Heritage Exhibition at the National Museums of Kenya

By Sultan Somjee

Somjee, S. Legacy of Colonialism, Tyranny of African Nationalism Viewing Asian African Heritage Exhibition at the National Museums of Kenya. Weber: The contemporary west Volume 33, Number 1, Fall 2016. pp. 25- 32

About the writer

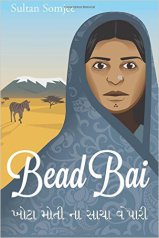

Sultan Somjee (PhD McGill), is an ethnographer and has curated several exhibitions and published widely. He curated the Asian African Heritage: Past and Present Exhibition (2000 – 2005) while he was the Head of Ethnography at the National Museums of Kenya. Thereafter, he wrote Bead Bai (2012) and Home Between Crossings (2016). Both books are about the Asian African experience from the 1900s to 1970s. In 2001 the United Nations named Dr Somjee one of the twelve global “Unsung Heroes of Dialogue Among Civilizations” in recognition of his foundational work.

Somjee 2016 Legacy of Colonialism, Tyran[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [411.4 KB]

The Asian African Heritage Identity and History

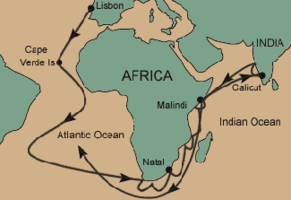

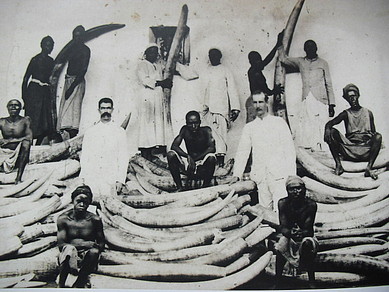

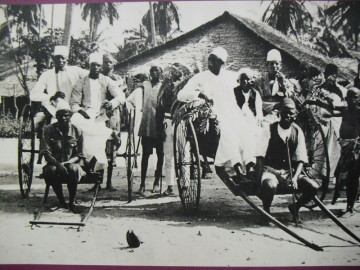

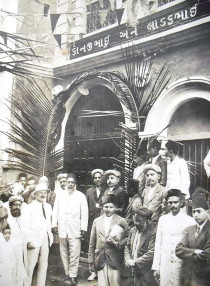

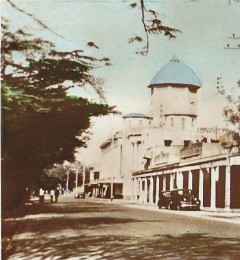

INTRODUCTION The presence of peoples from the Indian sub-continent in East Africa goes back well over three thousand years. The presence of peoples from Eastern Africa in India is also of long duration. (2) This exhibition focuses on the Asian African presence in Kenya, and relatedly East Africa, in a more recent period the last two hundred years.

The Asian African Heritage Identity and [...]

Adobe Acrobat document [493.1 KB]

Bead Bai

Sakina is an embroidery artist growing up in the shanty town of Indian Nairobi, a railroad settlement in British East Africa in the early 1900s. At home there are many storytellers like her stepmother, grandfather and uncle whose stories blend into histories of India and East Africa that flare her child’s imagination. In her tormented married life, while becoming a woman, Sakina finds comfort in the art of the beadwork of the Maasai.

Sultan Somjee

Click on photo

Asian Communities in East Africa

Asian Communities in East Africa

Asian Community in East Africa(1).pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [1.9 MB]

By Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

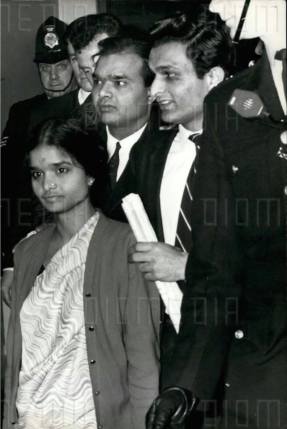

When Asians in Kenya were given the option of acquiring Kenyan citizenship and stay or maintaining their British passports and leave,21 year old Kenya born Vaid was among those who chose to leave for Britain.

But despite having a British passport, British officials refused her entry and instead sent her back to Kenya.

In Kenya she was rejected and put on a flight to Johannesburg South Africa so that she could find some of her relatives. But as soon as she arrived in Johannesburg the South African officials deported her back to Kenya.

Back In Nairobi Kenyan officials stood their ground and rejected her again, this time sending her to Athens Greece. Upon arrival in Greece, the authorities there refused her entry and sent her to Frankfurt Germany.

Since the Germans were not also willing to accommodate her, they flew her to Britain. After being stateless for two weeks and being shuttled more than 17,000 miles between Europe and Africa Vaid was eventually told she could stay with her two elder brothers in Britain but only for three months.

The great Asian exodus of 1969

The Lost Indians of Kenya

Salim Lone, New York City

October 7, 1971 Issue

To the Editors:

Early in 1969, Gordhandass Shah, a resident of Kenya for thirty-five years and holder of a British passport, was told by the government that under its new Immigration Act he was no longer able to continue working in Kenya, and that he should leave the country within three months. Being a British citizen, he contacted the British Embassy to make arrangements for moving to England. He discovered at the Embassy, however, that because he was not a white British citizen, there were severe restrictions on his right to enter Britain, and that in fact it would not be possible for him to go there in the foreseeable future.

When the three months the Kenya government had allowed Mr. Shah were up, he was arrested and tried in Criminal Court for being in Kenya illegally. His argument that the country of his citizenship, the only country he was eligible to go to, would not admit him was found unacceptable, and he was jailed, later to be deported to England.

By all counts, Gordhandass Shah is one of the luckier of the more than 200,000 East African Indians who hold British passports. Police escort for the journey to England notwithstanding, he was able at least to find a home and earn his livelihood. For the other thousands it is a much more painful story: they are unable to earn a living in Kenya, and they are not being deported to England, where they legally belong.

The Indian’s troubles started in the early 1960s. In the preceding seventy years, more than a quarter-million of them had been encouraged by Britain to settle in the East African colonies. Most of these Indians were traders, artisans, or lower professionals, occupying the middle position between black and white in the colonial hierarchy. They lived in their own large communities, segregated from both the Africans and the English. They were the essential instrument of British rule over the indigenous population, and had greater contact with the Africans than did the British. As such, they received more privilege than was granted the Africans, but by the same token they earned a lot more of the black resentment than the colonists did.

When Kenya received independence in 1963, the Indians were offered the choice of obtaining either British or Kenyan citizenship. Because the painful, post-independence experience of the Congo was still fresh then, and because many Indians felt that the growing demand for position and power from the newly educated African middle class would lead inevitably to their exclusion from the job market, only about 10 percent of the Indian population applied for Kenyan citizenship. The rest chose what later turned out to be “devalued” British passports.

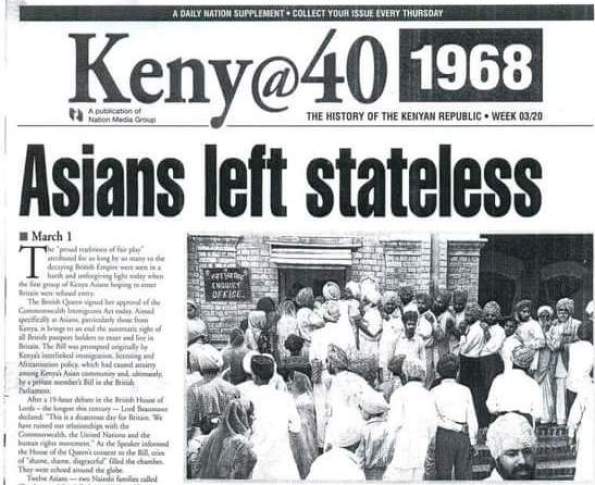

The current crisis began in 1968, when Kenya passed the first of its many laws that largely bar Indians with British passports from holding gainful employment. Almost simultaneously, the Labour government in Britain, expecting an influx of its colored citizens from the East African countries, limited to 1,500 the number of Indian families with British passports who could enter England annually.

As a consequence, there are now thousands of Indians in Kenya, unable to work there and denied the right to their legal homeland. As Nasir Butt, a father of seven who lost his job as an auto mechanic in 1968, said: “If we were victims of a natural disaster or running away from a communist country, we would have aid and interest. But now no one is interested, no one cares. We are not even considered refugees.”

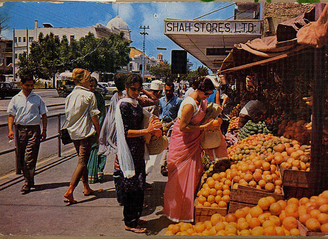

Most of these “refugees” are skilled in some craft or another, but now they can be seen walking the streets of Nairobi, Mombasa, and other cities; some have taken to begging, others live on charity, and many have moved in with those relatives and friends who can still make a living.

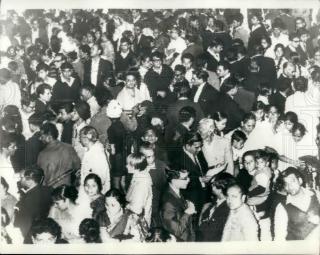

The more enterprising ones have tried by various means to publicize their cause. Small groups sometimes manage to sneak onto planes bound for England, where, of course, they are denied admission and put back on the plane to Kenya. But Kenya refuses to readmit them, because once an Indian leaves Kenya he cannot return except with a special visa. So these Indians begin a long trek, shuttled—without charge—from one world airport to another, until finally someone admits them—temporarily.

Because of the great distances these homeless groups travel, they have come to be called “migronauts,” and it is not unusual to meet these migronauts in the transit lounges of various world airports. I met one such group in Entebbe, Uganda, late last year—five teen-age boys who had only just begun their odyssey, having flown to Bombay, Entebbe, London, and back to Entebbe: “Only 15,000 miles so far,” said Virendra Desai, at nineteen the oldest of them. “We are human shuttlecocks in a long game. I wish someone would make a mistake.”

Those Indians still left in East Africa are gradually beginning to feel a rising hostility among the African masses. Fortunately there have been no incidents of overt violence so far, but unwanted and unclaimed, the Indians rather easily become the targets of witch hunts. Those Indians still trading are frequently singled out as the exploiters of the native population; the Indian community earlier this year was widely blamed—without presentation of any evidence—for a leakage of the national high-school examination in Uganda and Kenya; and last month Tanzania announced the nationalization of all property valued at over $15,000—but the New York Times correspondent there has reported that only property belonging to Indians has been expropriated.

The Indian community in East Africa is subdued and uncomfortable, and sometimes even fearful. The constant topic of conversation among the community is how best one can wrangle one of the 1,500 vouchers issued for entry into Britain each year, and large hordes will eagerly gather at the homes of those fortunate enough to win one of these vouchers to learn how the lucky ones presented their cases to the British Embassy. Every once in a while there are rumors in the community that Britain has decided to finally let all of its Indian citizens come “home,” while those more maliciously inclined circulate false news of massacres of Indians at the hands of Africans.

Two such rumors recently turned out to be true. A little over a year ago, an Indian family of four was ritually hacked to death in Nairobi. And last month the British government announced that it had doubled to 3,000 the number of Indian families who could enter Britain from East Africa each year. At that rate, it will take about twelve years for the unwanted and unemployed British East African Indians to make it “home.”

Salim Lone

New York City

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1971/oct/07/the-lost-indians-of-kenya/

East African Asians in 1960’s

East African Asians include Gujaratis and Punjabis who had migrated from the Indian subcontinent to Africa and then from Africa to the UK. They include Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Some are Ismaili Muslims, a Shi'a denomination, whose spiritual leader is the Aga Khan.

http://www.minorityrights.org/5415/united-kingdom/east-african-asians.html

More Coverage by CNN

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/12/11/world/africa/kenya-railways-india/index.html

Indians in East Africa

Two parts to a this story, one is that most of the Indians held British passports, after independence in the 1960s, each country adopted different policies towards Asian residents. For example, following Kenya’s independence from Britain in 1963, Asians were given two years to acquire Kenyan citizenship to replace the British passports that most Asians held. However the majority of Asians did not take up Kenyan citizenship, a pattern that was repeated in other countries of East and Central Africa after independence.

Second was naturally the “Africanization” policies of countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia and Malawi were intended to ensure that the African majority population acquired greater control over key areas of the economy and the government. Legislation was passed restricting the choice of residence, trade and employment for non-citizens.

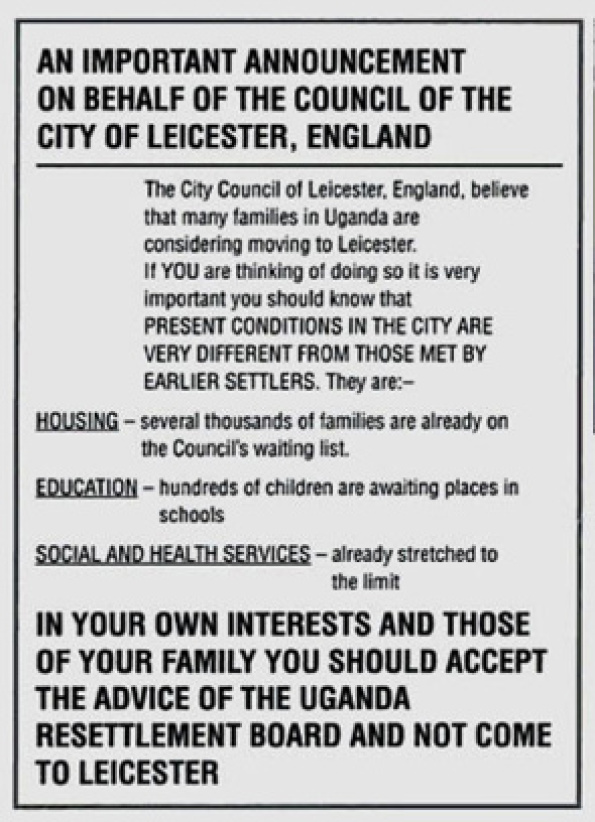

Getting back to Quota, towards the last few years of the 1960s, many East African Asians chose to migrate to the UK. Though they held British passports, they were not always welcome in the UK. The crisis began in 1968, when Kenya passed the first of its many laws that largely bar Indians with British passports from holding gainful employment. Almost simultaneously, the Labour government in Britain, expecting an influx of its coloured citizens from the East African countries, limited to 1,500 the number of Indian families with British passports who could enter England annually.

As a consequence, there were thousands of Indians in Kenya, unable to work there and denied the right to their legal homeland. As Nasir Butt, a father of seven who lost his job as an auto mechanic in 1968, said: “If we were victims of a natural disaster or running away from a communist country, we would have aid and interest. But now no one is interested, no one cares. We are not even considered refugees.”

East African Asian Crisis 1968-1976

During the 1960s, the last African countries still under imperial control regained independence from their European colonisers. The process of 'Africanisation' that followed was not straightforward. Economies suffered as political leaders struggled to unite communities in the face of drought and famine. The political instability brought danger for the large Asian communities in East Africa who had been brought from India by the British to help run their businesses.

http://www.20thcenturylondon.org.uk/east-african-asian-crisis-1968-1976

1968: More Kenyan Asians flee to Britain

Another 96 Indians and Pakistanis from Kenya have arrived in Britain today, the latest in a growing exodus of Kenyan Asians fleeing from laws which prevent them making a living

http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/4/newsid_2738000/2738629.stm

United Kingdom - East African Asians

http://minorityrights.org/minorities/east-african-asians/

COVER STORY: Filling gaps in history: Indians in East Africa

http://www.dawn.com/news/1075485

East African Asians in 1960’s

East African Asians include Gujaratis and Punjabis who had migrated from the Indian subcontinent to Africa and then from Africa to the UK. They include Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Some are Ismaili Muslims, a Shi'a denomination, whose spiritual leader is the Aga Khan.

http://www.minorityrights.org/5415/united-kingdom/east-african-asians.html

More Coverage by CNN

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/12/11/world/africa/kenya-railways-india/index.html

Tom Mboya came up with a plan called the "percentage plan" in 1964

By Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

One of the biggest problems the new government had to grapple with was the high unemployment among Africans.

To help solve the problem Mboya came up with a plan called the "percentage plan" in 1964.

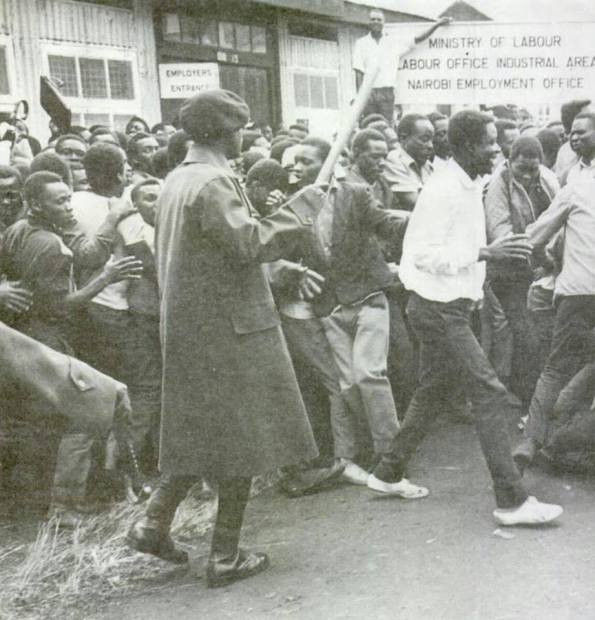

According to the plan, the government was to take in an extra 15% of unemployed Africans and private businesses an extra 10%.The plan was aimed at absorbing half of the 100000 unemployed Africans.

The plan was good but it soon ran into trouble. For when the jobless had registered it was found that the number of unemployed Africans had grown from 100000 to 160000.

Some private businesses began to dodge their 10% quota. More trouble arose when allegations from some job seekers started to come in that they were being asked "to cover the hand" of certain people in the way of bribes. Female job seekers also alleged that they were being asked to pay for employment in a certain way.

The administration of the "percentage plan" soon threw the ministry of Labour into turmoil. Officials at the ministry worked all night to deal with the flood of job seekers, but still it was like plugging a dam with your finger.

Special employment registration centres were set up all over the country. At certain registration centres there were riots and the police had to be called to handle the situation.

At Eldoret when the unemployed stormed the Labour registration office, the registration was moved to a tent in the middle of a football pitch. But within no time the tent was stolen by the job seekers.

At Bahati when a camp was opened for the unemployed who had come to register ,1000 job seekers took a second look at the fence and thought they were in prison ,it took the officers alot of smoothing down to stop them from breaking out.

To save the situation the International Labour Organisation recommended to the government the "one man/one job" system where those who operate business and hold official jobs should choose between the two. It also recommended more self- help and self- employment projects.

Ugandan Asians advert 'foolish', says Leicester councillor

Salutations of pioneers of Tribe 44

It is well-known and acknowledged fact that the Kenyan Asian community has since the early days of our history been intricately in the social economics, educational, health and political

sectors of its adopted motherland land in the words of writer Cynthia Salvador!

The presence of many Asian communities in Kenya has added much colour to the character, culture and economy of this great multiracial and multi ethnic nation.

Kenyans of Asian descent have thus been officially recognised as the country's 44th tribe. I recently met the activist who spearheaded the quest for recognition of members of this community

The pioneer activist is none other than a fifth generation Kenyan of Indian descent. Farah Manznoor HSC who at the meeting was accompanied by her brother Shahid Mehmood HSC and Uncle Mohamed Iqbal. Farah a resourceful and charming personality is the grandchild of Mohamed Din Bhutta, who served Railways during the colonial days. She noted that her grandfather played an honourable role in the freedom struggle of Kenya.

Born and educated in Kenya. Farah initially worked for the country's airline industry but later started managing Mothers Lap Foundation an NGO alongside her sibling. She is a proud agent of change and hope and continues to be a champion of women's rights. She has also been active in the fight against human trafficking and female genital mutilation in the last 15 years Farrah is thankful to His Excellency the President for accepting her petition and granting the community its wishes. She is also obliged to all those who supported her quest, in particular her family friends and Mr Joshua Odongo, a former vice-president aspirant and businessman. We salute Farah and her associates- their achievement has certainly led to improved integration of the Asian family in Kenya. Our ancestors and future generations of this illustrious tribe will always be proud of Farah.

Follow… Farrah Maanzoor Hsc