The Colonization of Kenya

The British East African Company was granted a charter in 1888, which led to the colonization of present day Kenya.

The British East African Company was granted a charter in 1888, which led to the colonization of present day Kenya. When the company became bankrupt the British government took over

administration of the colony which they intended to use a gateway to Uganda, Buganda and Bunyoro because there were no minerals to exploit in Kenya. In order to subdue the colony, the British

authorities forcibly took land, introduced forced labor and passed legislation that ensured natives became subjects of the British settlers.

The road to colonization of Kenya was difficult for the British because by the turn of the 20th century Indians outnumbered whites 2:1 and the Indian rupee was Kenya’s main currency.

It is reported that there were approximately 23 000 Indians and only 10 000 whites. As a means of consolidating power, the British introduced the hut tax in 1902. A certain amount of taxes was to be

paid to the government for each hut a family owned. This meant that native Kenyans had to earn money which could only be achieved by working for someone else that could pay them wages. The punishment

for not paying hut tax was a fine and which often when not paid led to forced labor thereby providing the British settlers with the cheap labor they were searching for.

As demand for labor increased, British settlers then introduced poll tax which was required of every citizen in the country. In addition, Kenyans had to work for 60 days a year for the

government unless they were already employed by British settlers. This led to the creation of native reservations which were often situated far from major roads and rail and whose soil was not

conducive for farming. A lot of measures employed by the British settlers in Kenya were imported from South Africa and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

In 1913, the government passed a land bill that gave the white British settlers 999 year leases on the land and effectively created a monopoly on land use. Later, in 1919 British settlers

introduced the Kipande system that required all Kenyan men to wear identity discs similar to the chitupa introduced in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) which limited movement labor.

The Colony and Protectorate of Kenya was established on 11 June 1920 when the territories of the former East Africa Protectorate (except those parts of that Protectorate over which His

Majesty the Sultan of Zanzibar had sovereignty) were annexed by the UK. The Kenya Protectorate was established on 13 August 1920 when the territories of the former East Africa Protectorate which were

not annexed by the UK were established as a British Protectorate. The Protectorate of Kenya was governed as part of the Colony of Kenya by virtue of an agreement between the United Kingdom and the

Sultan dated 14 December 1895.

In the 1920s natives objected to the reservation of the White Highlands for Europeans, especially British war veterans. Bitterness grew between the natives and the Europeans. The

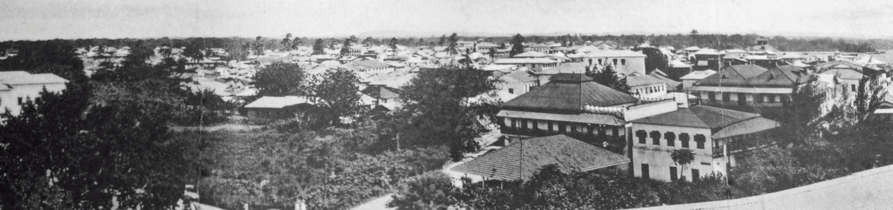

population in 1921 was estimated at 2,376,000, of whom 9,651 were Europeans, 22,822 Indians, and 10,102 Arabs. Mombasa, the largest city in 1921, had a population of 32,000 at that

time.

Native Kenyan labourers were in one of three categories: squatter, contract, or casual.[C] By the end of World War I, squatters had become well established on European farms and

plantations in Kenya, with Kikuyu squatters comprising the majority of agricultural workers on settler plantations. An unintended consequence of colonial rule, the squatters were targeted from 1918

onwards by a series of Resident Native Labourers Ordinances—criticised by at least some MPs —which progressively curtailed squatter rights and subordinated native Kenyan farming to that of the

settlers.

The Ordinance of 1939 finally eliminated squatters’ remaining tenancy rights, and permitted settlers to demand 270 days’ labour from any squatters on their land. and, after World War II, the

situation for squatters deteriorated rapidly, a situation the squatters resisted fiercely.

In the early 1920s, though, despite the presence of 100,000 squatters and tens of thousands more wage labourers, there was still not enough native Kenyan labour available to satisfy the

settlers’ needs. The colonial government duly tightened the measures to force more Kenyans to become low-paid wage-labourers on settler farms.

You may travel through the length and breadth of Kitui Reserve and you will fail to find in it any enterprise, building, or structure of any sort which Government has provided at the cost

of more than a few sovereigns for the direct benefit of the natives.

The place was little better than a wilderness when I first knew it 25 years ago, and it remains a wilderness to-day as far as our efforts are concerned. If we left that district to-morrow

the only permanent evidence of our occupation would be the buildings we have erected for the use of our tax-collecting staff.

—Chief Native Commissioner of Kenya, 1925

The colonial government used the measures brought in as part of its land expropriation and labour ‘encouragement’ efforts to craft the third plank of its growth strategy for its settler economy: subordinating African farming to that of the Europeans. Nairobi also assisted the settlers with rail and road networks, subsidies on freight charges, agricultural and veterinary services, and credit and loan facilities. The near-total neglect of native farming during the first two decades of European settlement was noted by the East Africa Commission.

https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/african-history/the-colonisation-of-kenya/

Timeline of Mombasa

Why Moroccan Scholar Ibn Battuta is the Greatest Explorer of all Time

https://www.history.com/news/why-arab-scholar-ibn-battuta-is-the-greatest-explorer-of-all-time

The Africans: A Triple Heritage - Program 1: The Nature of a Continent

Black Man's Land: Images of Colonialism and Independence in Kenya; White Man's Country ep 1 of 3

Otenyo Nyamaterere, the slain 1908 Kenyan anti-colonial hero whose head is still in a British museum

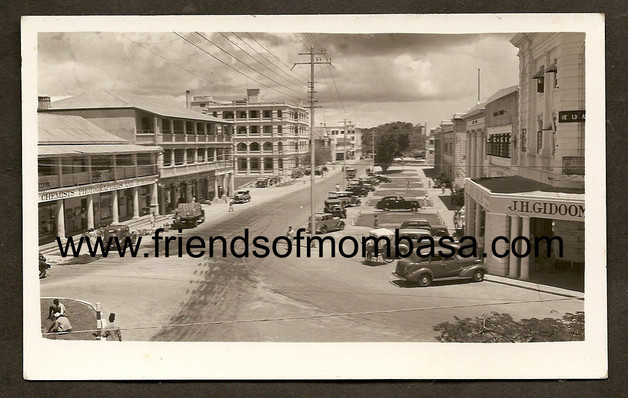

Kenya, Vintage Post cards, click below...

Kenya Timeline

A time line overview of big and small events in the history of Kenya.

http://crawfurd.dk/africa/kenya_timeline.htm

Kenya in history

Kenya History (photos)

https://www.facebook.com/KenyaHistory101?fref=photo

Development of Banking in Kenya

The financial journey in Kenya dates back to the pre-colonial periods. At first, the pioneering banks concentrated on financing international trade along the Europe-South Africa–India axis. They, however, soon diversified operations to tap the opportunities for profitable banking created by a growing farming settler community and pioneer traders in the local economy to whom they provided deposit and credit facilities. It was only a matter of time for banking to spread into the interior.

It all started with Indian money lenders operating quasi bank services probably as early as the 18th century but the first recognisable bank was Jetha Lila Bankers from India, which was established in Zanzibar in 1880. In 1889 the National Bank of India appointed the trade house of Smith Mackenzie to be their agent in Zanzibar. Smith Mackenzie had a Mombasa branch in 1887 which was taken over by the Imperial British East Africa (IBEA) in 1888. The National Bank of India established its own office in Zanzibar in 1892. In July 1896 the National Bank of India established a branch in Mombasa renting premises from Sheriff Jaffer. The spread continued to 1904 when they opened a branch in Nairobi.

https://www.centralbank.go.ke/banking-development/

NATIVE TRIBUNALS IN KENYA

ARTHUR PHILLIPS

Photographs by the Kenya Information Office.

Apologies in advance to all, in case there is any derogatory language used by Mr Arthur Phillips, and thus in case it offends any individual, these articles are an extract from a 1946 historic

book.

People of colour are usually seen or made to feel that their ancestral back ground were hardly structurally incapable of being in a society or were somewhat back ward.

Since, victors always write their own version of history, it is never the less observable to witness what Africa has had to offer in terms of its artefacts in many different forms of its history,

that stands as an indorsement to this very day.

Fast forwarding to the free for all Europeans “ Scramble for Africa”: Berlin Conference of 1884-85 that kicked off and offloaded, plunderers, raiders, rustlers that were backed by many European

governments, since Africa was under illegal occupation and many of it’s infrastructures destroyed to make way for the so called “New World”.

The Cultural, ethics, integrity, beliefs, principles had somewhat eroded through time, but can still be witnessed to this day in many cities, towns, villages, rural areas...etc.

This is a historical tale or documentation that has lingered for many many years, of such small/large administrative hearing amongst its own people, a judicial process in dealing with many

different disparities amongst its society at large, that we now call it “the court”…

In a sense, the native tribunals existing today in the tribal areas are the lineal descendants of the pre-existing indigenous judicial bodies.

There is probably no other branch of public affairs in Kenya in which there has been such a great devolution of responsibility to Africans as in the administration of justice. Many people would

doubtless be surprised to learn how extensive are powers granted to native tribunals. In a recent case in which the claim was for £200 in connection with the dissolution of a business partnership, it

was desired magistrate’s court, but it was found that even a First Class Magistrate had no jurisdiction to try a case involving such a large sum of money. The only court, other than a native

tribunal, which was competent to try the case was the Supreme Court.

In the vast majority of cases in which Africans go to law with one another it is to a tribunal of their fellow-Africans that they must look for the determination of their rights. The Tribunals’

powers of adjudication, moreover, are not confined to civil disputes. They are authorised to try a wide range of criminal offences and to award punishments, including imprison-for a period up to six,

and in some cases twelve months.

A Very large percentage of the criminal cases arising in the “native reserves” are tried by native tribunals. What is the origin and history of these tribunals? How are they constituted? What form of

procedure do they adopt? What kind of records do they keep? What law do they administer? What control is exercised over them and—perhaps the most frequently-asked question of all—what are their

standards of efficiency and integrity? I can do no more in this article than deal with these questions in the briefest outline.

ORIGIN AND HISTORY

In a sense, the native tribunals existing today in the tribal areas are the lineal descendants of the pre-existing indigenous judicial bodies. At an early stage in the history of the East Africa

Protectorate legal recognition was given to the jurisdiction, both civil and criminal, of the “Courts” of certain tribal “Chiefs and Elders.” The Native Courts Regulations, 1897, laid down the policy

with regard to such Courts as follows: —

“The Sub-Commissioner and Collector shall exercise in their administrative capacity all reasonable supervision within their power over the procedure and punishments used by the tribal authorities

. . . but shall not disallow or unduly interfere with their orders and punishments unless such orders or punishments are essentially inhuman or unjust, as, for example, where convictions are obtained

by witchcraft or torture or entail barbarous penalties such as mutilation, cruel corporal punishment, or the enslavement of a condemned person or his relatives.”

The type of “Court” which was thus accorded legal recognition differed, of course, fundamentally from the modern European conception of a Court of Law. It was more in the nature of a family or

clan council. It must be remembered that most Kenya tribes—as distinct from many tribes in other parts of Africa, e.g., the Baganda—possessed no centralised political organisation. The rudiments of

government in these primitive communities seem to have manifested themselves not so much in the exercise of political authority by a definite person or body of persons over a certain territory as in

the maintenance of equilibrium between the various lineage groups.

In most tribes, therefore, the indigenous system of justice was very fluid; there appears to have been no standing judicial body; disputes were adjudicated upon by ad hoc councils of elders,

usually within the framework of clan relationships; the composition of the judicial body was liable to vary with the nature and importance of each individual case; and the sanction behind its

decisions was the solidarity of the group. The only step in the direction of an organised judicial system was the recognition of certain elders as traditionally qualified to participate in

adjudication and this recognition was based to a large extent on their seniority in the social unit.

Institutions of this type could hardly be expected to survive unchanged in association with the new “set-up” resulting from the establishment of a strong central government with overriding

authority. It was found, in particular, that the official “headmen” appointed by the Government—who generally represented a new and alien institution in tribal society—tended to exert an unduly

dominant influence over the tribunals; and efforts were made (e.g., by Sir Percy Girouard about 1911) to restore and reinforce the authority of the elders and to make the tribunals conform more

closely to the indigenous pattern.

The subsequent course of events suggested, however, that the necessity for development and reorganisation on more modern lines was inescapable. That is not to say that in the early stages this

process was very rapid. The condition of the native tribunals shortly before the last war may be illustrated by a case reported in the East African Law

Reports for the year 1913. A Kikuyu “Kiama” had tried, sentenced and executed certain persons who were suspected of practising witchcraft.

The condemned men had been placed in a hut and then relatives had been compelled to set fire to it. The Kiama elders, fifty-four in number, were tried for murder. The Supreme Court held that they had acted in good faith, believing that they were entitled to exercise “the powers which they had had from the beginning of things.” The elders were found guilty, therefore, of a lesser offence than murder, and each of them was sentenced to one day’s imprisonment and a fine of fifty rupees.

MODERN DEVELOPMENTS

After the last war it was increasingly realised that the tribunals, if left to their own resources, would be incapable of adjusting themselves satisfactorily to changing conditions. A policy of

closer supervision was adopted, and this led inevitably to measures of re-organisation which often involved a considerable departure from the pattern of indigenous institutions.

During the last twenty years development in the direction of a modernised system of courts has proceeded apace, particularly in the Kavirondo and Kikuyu districts. Among the main features of this

process have been the establishment of standing judicial bodies with a fixed personnel; reduction of the number of tribunals by amalgamating small local units and centralising jurisdiction in a

“divisional” tribunal on a territorial basis; drastic reduction of the number of elders sitting on each tribunal; the provision of modern-style court-houses; and the creation of a hierarchy of

authorities empowered to hear appeals. Another change introduced in comparatively recent years was the exclusion of Government “Chiefs” from the tribunals, in accordance with the principles of the

separation of executive and judicial powers.

Two other noteworthy features of the present system must be mentioned. Firstly, for all practical purposes the native tribunal system is independent of the Supreme Court and is entirely controlled by the officers of. the Provincial Administration.

Secondly, advocates and legal practitioners are debarred from appearing before a native tribunal, or before a District Officer or Provincial Commissioner on the hearing of an appeal from a native

tribunal. The legislation imposing these conditions was introduced in 1930, and, although of a somewhat controversial nature, it was

supported by the then Attorney-General on account of the necessity for protecting Africans against certain dangers and abuses which had already begun to manifest themselves—in particular, an excess

of technicality in procedure and exploitation by lawyers’ touts.

A further step in the same direction was taken in 1942, when an Ordinance was passed which had the effect

of removing native land cases entirely from the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and making it obligatory for such cases to be filed in a native tribunal. (In all other classes of cases, Africans

are legally entitled to institute proceedings in one of the ordinary courts of the Colony, rather than in a native tribunal, if they so desire.)

TRIBUNALS OF THE PRESENT DAY.

There are now approximately 140 native tribunals in Kenya. In the majority of districts the number of members sitting on such tribunal is from five to ten; but of these a certain proportion usually consists of members drawn from a panel, who serve in rotation for a few months at a time. The method of selecting elders for appointment to the tribunals varies considerably. African opinion is normally consulted, sometimes by means of elections (though this method has been abandoned in many districts as unsatisfactory for the purpose of judicial appointments). The final selection usually rests with the District Commissioner. The latter’s recommendations are submitted to the Provincial Commissioner, who issues the warrant establishing, the tribunal and prescribing its powers.

In an article of this kind it is not easy to avoid misleading generalisations. It must, therefore, be stressed that among the large number of existing native tribunals there is a very great diversity, attributable to such factors as environment, stage of civilisation and tribal characteristics. In one district, the elders may be found squatting under a tree, scarcely distinguishable from the crowd which surrounds them, while in the centre of the group the disputing parties argue their case with much clamour and gesticulation. In another district, the tribunal sits in a permanent building with a raised bench, witness-box. and all the panoply of a modern court.

The amount of business conducted varies greatly, and it is interesting to note that to a large extent these variations correspond with racial differences. The Bantu are everywhere the most litigious. In South Kavirondo, for instance, the Kisii (a Bantu tribe) are responsible for far more litigation than their more numerous Nilotic neighbours the Luo: while the Luo in their turn are more addicted to going to law than the Nandi or the Masai—tribes with a Hamitic strain. Among the more litigious tribes the “appeal habit” tends to be carried to extremes, with the result that the same case is sometimes heard by four different courts in succession, viz., tribunal of first instance, appeal tribunal, District Officer and Provincial Commissioner. As an indication of the volume of judicial business conducted by native tribunals in the larger districts, it may be mentioned that in 1942 the total number of cases heard and decided by the tribunals of the three Kavirondo districts was 39,590.

In civil cases, the majority of claims are founded on native law and custom and relate to such matters as stock transactions, bride-price, custody of wives

and children and (of special importance nowadays) land tenure. Actions for the recovery of cash debts are numerous, however, and there is an increasing amount of litigation of a “non-indigenous”

character, ie.. disputes concerning partnership, rent, hire of chattels, sale of goods, money- lending, and business contracts of various kinds-for which native law and custom affords little or no

precedent.

With regards to criminal jurisdiction, the tribunals are empowered to administer a great variety of statutory enactments, including parts of the Penal Code and many other Ordinances, Rules and Regulations. In addition to trying cases of theft and assault and other offences against person and property, the tribunals are largely responsible for the enforcement of legislation and of administrative orders on such subjects as the conservation of soil, water and timber; grass fires; control of intoxicating liquor; public health; witchcraft; tax collection; communal work on roads, etc., etc. The bulk of their criminal work falls within these categories, but there are still a certain number of cases which are classed under the heading of “offences against native law and custom,” the most noteworthy instance being prosecutions for adultery. Convictions and sentences in criminal cases are normally treated as being subject to confirmation by a District Officer; and, in addition, monthly returns of criminal cases have to be submitted to the Attorney-General.

Many tribunal elders—probably the majority—are illiterate; but each tribunal has a clerk who receives the fees and keeps a register of cases, showing the names of the parties, the cause of action and the tribunal’s decision. In one or two tribunals an attempt has been made to keep fuller records of the proceedings, including notes of the evidence.

The mode of procedure adopted in the hearing of cases varies greatly, but in the more advanced districts there is a tendency towards greater formality and in some tribunals the procedure is

beginning to approximate to that of a European magistrate’s court. Although there is a growing appreciation of the need for proof by means of proper evidence (including documentary evidence where it

is appropriate), it is still a common practice for the elders to fall back on the use of native oaths for the purpose of determining issues of fact. Trial by ordeal, however, is a thing of the

past.

FUTURE OF THE TRIBUNAL SYSTEM.

Does the quality of the justice administered in the native tribunals warrant the policy of investing them with such considerable powers? Is the Government justified in giving them the backing of

its own authority and allowing them to exercise those powers in the name of British justice? Is the government justified in giving them the backing of its own authority and allowing them to exercise

those powers in the name of British justice?

It is impossible, without over-simplification, to answer these questions in a few words. It may be stated, however, that from the outset the Government’s policy has been based on the recognition of

existing native law and custom and on the assumption that the encouragement of an evolutionary process of development is preferable to a “steam-roller” policy of modernisation.

In addition, it is relevant to ask, is there really any practicable alternative to the existing system?

While it will be readily admitted by those who know them that the native tribunals have many imperfections it may fairly be claimed that the history of their development during the last fifteen

years (i.e., since the present Native Tribunals Ordinance became law) shows a record of substantial progress towards greater efficiency and (in some districts at any rate) a higher standard of

judicial integrity. It is probably true to say on the whole, the tribunals accurately reflect the stage of advancement of African society in their respective districts.

If the existence of the native tribunals is to be justified on these grounds, the need for further and rapid improvement must of course, be accepted as a necessary corollary. In pursuance of this objective, special measures of investigation and planning have been instituted. Among the subjects under examination are the machinery of the tribunal system (with particular reference to the appellate authorities); its relation to the judicial system of the Colony as a whole; the qualifications, selection and training of African personnel; the provision of additional supervisory staff; the improvement of the tribunals’ records; and special problems such as those connected with criminal jurisdiction and with the establishment of native tribunals in towns mid other non-tribal areas. All these subjects require careful and specialised study.

Perhaps the most important and complex problems of all however, are those relating to the evolution of native law. In certain fields (e.g., land tenure, marriage, succession) there is an urgent need for the adaptation of customary law to rapidly changing conditions in others (e.g, in the field of “ commercial law” new principles and rules have to be incorporated into the body of the administered by the tribunals.

It is, moreover, hardly to be expected that a purely unwritten law will provide a satisfactory basis for the organisation of African society in the future; hence it may be necessary before long to undertake the recording of native law.

In the handling of these problems it will be of prime importance to reconcile the requirements of a simple, cheap and expeditious system of justice, adapted to African needs, with the English constitutional principle of the “Rule of Law” on which the legal system of Kenya is based.

History of Kenya

If one really needs to establish what the Indian community were all about in terms of East African history, well it goes well beyond East Africa, in fact history of the Indians is only concentrated in the East African Region seen as a core/hub for trading and thus for obvious reasons, due to major trading factors along the Eastern Coast of Africa.

Indians and Arab history recorded in that region dates back many centuries, the initial levy system was introduced by the Portuguese much later on and also by the British in the 1900's, which was hated by the Arabs and Indians alike.

Indians had a hand in everything along the East African Coast, trading in their own Currency, Financial/banking system was operated by the Indians, transport, trades carried out over the waters as far as India and beyond, Distribution, Wholesale, Retailing, Farming, Transport Inlands, etc. Indians and Arabs who built up century’s worth of historic trade in the region were systematically targeted and stripped off as time went by, by the colonial government.

The Indians were great traders in many aspects and business, in 1910 Sir John Kirk remarked on the work of Indian Traders in Nairobi: In fact drive away the Indians and you may as well shut up the Protectorate. It is only by means of the Indian Trader that articles of European use can be obtained at moderate prices.

Winston Churchill in “My African Journey”: It is by Indian labour that the one vital railway on which everything else depends was constructed.

In most European’s minds the Indians simply did not matter. When writing of East African history in general, the role of Indians is ignored or slighted. It is the British that get the credit for ‘pluck and determination’ building the Railways even when it is admitted that Indians suffered untold horrors.

Most if not all prime geographical areas were also chosen for themselves (Europeans) and area controlled by the British Europeans for the Europeans. The lack of information about Indians is due not only to the non-Indians’ disinterest (and often hostility). It is due also to the Indians’ own lack of Interest in writing about themselves.

The question is, we had the British Colony at that time in India and were happy to oblige with the building of East Africa in terms of labour, therefore why is it that most of the Indian people who came over who had farming experiences were never given any sort of land to farm in East Africa but the British government opted for South African Caucasians to be brought over with a premise on allocation of prime free land?

Mombasa was visited by the unknown Greek who wrote the Vtriplus in the first century A.D., who refers to it under the name of Tonike.

Arab colonisation of the East Coast is believed to have begun about the eighth century. The Portuguese first appeared on the coast when Vasco da Gama passed along it in 1498 on his way to India, and during the following century they succeeded in firmly establishing their power, and ruled with the aid of tributary Arab sultans.

Mombasa was occupied by the Portuguese early in the sixteenth century, and the great Port of Jesus was commenced there in 1592. It was wrested from them by the Arabs in 1698 after a siege of thirty- three months, and has been the scene of much bitter fighting, and has several times changed hands.

Until East Africa was partitioned amongst the European Powers towards the end of the last century, most of the coast came under the rule of the Sultan of Zanzibar, and the trade at Mombasa, Zanzibar and Bagamoyo, the principal ports, was controlled mainly by British and Indian merchants.

In 1877, Sultan Bargash offered to Sir William Mackinnon, Chairman of the British India Lino (or to a Company to be formed by him), a concession under lease for seventy years of the customs and administration of the whole of the dominions of Zanzibar, including all rights of sovereignty, with certain reservations in respect of Zanzibar and Pemba Islands. Mackinnon found, however, that he could not obtain the support of the British Foreign Office, and therefore declined the offer.

Joseph Thomson, author of Through Masai-land, was the first European to visit the Highlands of Kenya (in 1883). He was followed in 1885 by Hannington, first Anglican Bishop of East Africa.

In 1884, Sir H. H. Johnston obtained concessions from chiefs in the Kilimanjaro region, and later in the same year German agents secured concessions in the same area. The British Government raised no objection to the German acquisition, but put forward claims of its own to the hinterland of Mombasa.

A provisional agreement between the British and German Governments in 1886 determined the boundaries of the mainland territories of the Sultan of Zanzibar. Other frontier agreements were made with Germany in 1890 and 1893, and with Italy in 1891, fixing the boundaries of their respective spheres of interest.

In 1887, Sultan Bargash granted a concession for fifty years to a company formed by Mackinnon, first known as the British East Africa Association, which covered his mainland possessions not falling within the German sphere. This territory, which extends ten miles inland, is now known as the Kenya Protectorate, and the Sultan of Zanzibar receives an annuity for it.

In April, 1888, the founders of the British East Africa Association formed themselves into a Company, the Imperial British East Africa Company, with a capital of £240,000. A Royal Charter was granted the following September.

While efforts to secure territory in East Africa by German Companies and individuals received the backing of the German Government, the Imperial British East Africa Company carried on unaided its burden of national responsibility up to the end of 1890. The capital was quite inadequate for the scope of its undertakings, and a large part of this had been used up in costs of military operations in Uganda.

They sustained a further heavy loss when, in 1892, the British Government declared that the dominions of the Sultan of Zanzibar came within the free trade zone under the Congo Basin Treaty. The Company’s dues were thus swept away, but their rent and administrative expenses had still to be paid. Sir William Mackinnon, who had been the Company’s moving spirit throughout, died in June, 1893. In 1895 the British Government finally agreed to purchase the Company’s rights for £250,000.

Although the Company proved a commercial failure, involving its shareholders in loss, the promoters were mainly animated by motives of patriotism, and a desire for the abolition of the slave trade and betterment of the native peoples.

From 1 July, 1895, the Foreign Office assumed responsibility for the Company’s territory ; a commissioner was appointed ; and the name was changed to the East African Protectorate. Hitherto the Territory was usually referred to as “ Ibea,” from the initials of the Company.

The railway from the coast to Lake Victoria was undertaken by the British Government in 1895 at their own expense. Lord Salisbury’s decision to carry out this work was based on his desire to suppress the slave trade and to provide access to the headwaters of the Nile. It was completed from Mombasa to the Lake in 1901.

The length of the line from Mombasa to Kisumu is 577 m. compared with 703 m. by the old caravan route. It ascends to 8,322 ft., and descends again to 3,726 ft., the level of Lake Victoria.

A considerable amount of Indian labour had been used in the construction of the railways, and some thousands of Indians remained in the country.

The first applications for land were made in 1902, and the following year hundreds of settlers began to arrive. Among them were men of good standing from England, and Lord Delamere, who was one of the first, became the leader of the European immigrants in East Africa. Many of the settlers were Butch and English-speaking South Africans.

In 1905, the Territory’s administration was transferred to the Colonial Office.

In 1906, in view of the increasing number of European settlers, a nominated Legislative Council was set up on which seats were given to their representatives.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, as the Duke and Duchess of York, visited Kenya in 1924.

In 1914-18, Kenya was the base for operations against German East Africa; in 1940-41 against Somalia and Ethiopia; and in 1942 against Madagascar. After each war there was a considerable influx of British settlers as farmers or technicians, and Indian artisans and tradesmen.

The Visit of H.R.H. Princess Elizabeth and Duke of Edinburgh, who were staying at Sagana Lodge, Kenya, was interrupted by the death of H.M. King George VI on 6 Feb. 1952.

In 1959 H.M. Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, visited Kenya.

Mau Mau Terrorist Activities:—Though a State of Emergency was declared by the Kenya Government in 1952, as a result of widespread outrages attributable to the Mau Mau organisation and was still in force up to the end of 1959, conditions had in fact improved very considerably, and the State of Emergency was ended.

In January, 1960, the Emergency Powers Ordinance was repealed and the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance came into force immediately thereafter.

1 Aug. 1961. Release of Jomo Kenyatta.

Recent Governors.

1944. Sir P. E. Mitchell, G.C.M.G., M.C.

1952. Sir Evelyn Baring, G.G.M.G., K.C.V.O.

1959. Sir Patrick Renison, K.C.M.G.

The Tragedy of Individualizing the Commons

The Outcome of Subdividing the Maasai Pastoralist Group Ranches in Kajiado District, Kenya.

Dr Marcel Rutten (African Studies Centre - Leiden)

INTRODUCTION

This article is based on research carried out in early 1990 among the Maasai pastoralists of the Kajiado District, Kenya (see figure 1). The survey has foremost been a review of the Maasai pastoralists use and ownership of land from a geographer's perspective, while taking into account ecological, economical, and socio-cultural aspects. The process and consequences of the individualization of land ownership in the Maasai area as it developed over the last century has been studied and special attention has been given to the effects of the subdivision of group ranches started in 1986.

Land Treaty The Tragedy of Individualizi[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [2.6 MB]

KENYA COLONY AND PROTECTORATE.

Immigration, Income Tax Ivory

The Colony and Protectorate is bounded on the east by Somalia and the Indian Ocean ; on the north by Ethiopia ; on the north-west by the Sudan ; on the west by the Uganda Protectorate and Lake Victoria ; and on the south by Tanganyika Territory.

This territory was formerly known as the British East Africa Protectorate. In July, 1920, the Protectorate, except for the portion under the dominion of the Sultan of Zanzibar, was declared to be a Crown Colony under the title of Kenya Colony.

Kenya Protectorate consists of the mainland dominions of the Sultan of Zanzibar, being a strip of land extending ten miles inland along the coast from the Tanganyika border to Kipini, together with the islands of the Lamu Archipelago. In respect of this area, the Sultan receives an annuity of £10,000.

Nairobi is the Capital of the Colony and Protectorate and the chief port is Mombasa.

The name Kenya is taken from the native name for Mount Kenya, Kilinyaa, meaning the White Mountain.

Administration.—The Colony and Protectorate are administered under the Colonial Office by a Governor.

Under the Constitution Order in Council of 30th November, 1960, the general terms of which were agreed at the Constitutional Conference of 1960, Legislative Council is composed of a Speaker, appointed by the Governor on the Queen’s instructions received through a Secretary of State, fifty-three Constituency Members elected on a common roll, twelve National Members elected by the Constituency Members, four official Ministers, and a number of Members nominated by the Governor in pursuance of instructions given to him by the Queen through a Secretary of State.

The General Election took place in Feb., 1961, and the Governor subsequently appointed 12 Nominated Members. Of the fifty-three constituency seats, ten are reserved for Europeans, three for Asian Muslims, five for Asian non-Muslims, and two for Arabs. Of the twelve national seats, four are African, four European, one Asian Muslim, two other Asian and one Arab.

A British subject or British protected person over 21 who is literate in any language or is over 40, or has an annual income of £75, or has property valued at £200, or is one of any number of wives of a person with an annual income of £75 or property valued at £200, or holds one of a number of scheduled offices can register as a voter. Over 1,300,000 persons registered as voters for the General Election.

General Election.—A general election took place in February, 1961. The Legislature comprises ten seats reserved for Europeans, five for Asians not of the Muslim faith, three for Asians of the Muslim faith and two for Arabs. In addition there are thirty-three open seats and twelve seats for “ national ” members elected by the fifty-three constituency members.

Candidates for the reserved seats participated in primary elections during January to ascertain if they enjoyed a reasonable degree of support from members of their own race or creed. Successful candidates then contested a further election at which electors of all races were entitled to vote.

At the general election in February voting took place in thirty-five of the forty-four constituencies into which the Colony was divided, there being nine unopposed returns. The polling period passed without incident and African candidates were successful in all but one of the open seats, thus achieving a majority in the Legislature.

Kenya’s “ Framework ” Constitution.—The Kenya Constitutional Conference in London, Feb./Apr. 1962, ended with the signing by almost all of the delegates of the Colonial Secretary’s paper setting out a “ framework ” constitution for Kenya. Mr. Maudling’s proposals included provision for an impartial and independent judiciary and a Bill of Rights guaranteeing the proper protection of individuals which should be enforceable in the courts.

There would be two chambers in the Parliament. The Lower House would be elected by universal adult suffrage and based on single-member constituencies. The Upper House would consist of one member from each of the existing districts. Consideration should also be given to the inclusion in the Upper House of non-voting members representing special interests.

There should be a strong and effective Central Government responsible to the Central Parliament, which would be responsible for a very wide range of activities. Subject to the foregoing, there should be the maximum possible decentralisation of the powers of government to effective authorities capable of a life and significance of their own, entrenched in the constitution and drawing their being and power from the constitution and not from the Central Government.

Six Regional Assemblies would be established. The Regions would have administrative powers some of which would be exclusively reserved

to the regions and entrenched in the constitution. Other administrative powers, including administration of Central Government functions, would be delegated by agreement with the Central Government. In some matters the Regional Assemblies would have exclusive powers of enactment having the force of law. In other matters they would have either concurrent powers or powers of making byelaws.

Control of land transactions outside the present scheduled areas should be vested in the appropriate tribal authorities. The constitution would also establish a Central Land Board with sole responsibility for the formulation and implementation of settlement schemes in the settled areas.

The Central Government would be responsible for the Armed Forces and the ultimate sanction of law and order, but the day to day responsibility for law and order within each region would rest with the National Assembly.

Formation of Coalition Government.—Details of the constitution based on this framework will be settled by the Kenya Coalition Government in discussion with H.M. Government. The Coalition Government has been formed also to increase national confidence and unity and to continue good government.

The formation of the Coalition Government, which will be led by the Governor, has been completed in Nairobi by the Acting Governor of Kenya, Mr. E. N. Griffith-Jones. The size of the Council of Ministers has been increased to 16. The Governor has agreed with the leaders of the two African political parties that the two official Ministers now responsible for the portfolios of Legal Affairs and Defence, Mr. A. M. F. Webb and Sir Anthony Swann, should retain these portfolios. It has also been agreed that Mr. Ronald G. Ngala (KADU) and Mr. Jomo Kenyatta (KANU) will be respectively Minister of State with responsibility for Constitutional Affairs (in liaison with the Governor’s Office) and for the Administration; and Minister of State with responsibility for Constitutional Affairs (in liaison with the Governor’s Office) and for Economic Planning.

As soon as possible after these details had been settled and the necessary instruments for an internal self-government constitution had been made, a general election would be held and that constitution would be introduced. Certain steps, such as registration of voters and delimitation of the Regional boundaries, could and would be taken before these details were finally settled. Thereafter further negotiations would be needed on arrangements for full independence, which Her Majesty’s Government reaffirm to be their aim for Kenya.

A council of State was formed in 1958, with powers of delay and revision to protect any one community against discriminatory legislation harmful to its interests. It has been continued under the new Constitution. It consists of a Chairman, and ten members nominated by the Governor and drawn from all races in Kenya. Four hold office for 10 years, three for 7 years, and three for 4 years.

A considerable measure of local self-government is exercised by the African District Councils, of which there are 33. There are Municipalities K.A.N.U. = Kenya African National Union.

Mau Mau: Black My StoryLike Page

Yesterday at 05:00

When the Europeans arrived in Kenya about a hundred years ago they saw a beautiful country overshadowed by a great snow peaked mountain. The Africans living around this mountain called it

Kirinyaga (the ostrich mountain). The newcomers renamed the mountain and called it Mt. Kenya from which the country's name is derived.

The climate was good and the land was fertile. There was plenty of water from the hundreds of rivers which flowed through the land of Kirinyaga. The soil, wetted by the country's plentiful

rainfall, could support all types of agriculture. There were forests where the Africans obtained their firewood, and grasslands where they grazed their cattle, sheep and goats. African settlements

were scattered all over the countryside, from the Indian Ocean coast to the shores of the "great lake". Here they cultivated their crops, cherished and enjoyed a civilization of their

own.

At first the number of European settlers in the country was small. The colonial government was doing all it could to bring in more white settlers. Very attractive terms for the granting of

African land to the settlers were put forward. An acre of the best fertile land in the Highland plains was sold as cheaply as two shillings and fifty cents. Land was leased to the settlers for

periods of 99 years or rented a hundred acres at the rate of twenty shillings every year..

With total disregard of the Africans, the Europeans started alienating huge tracts of land. Thousands of square miles of Kikuyu land in Kiambu, Mweiga in northern Nyeri and in the Rift

Valley were taken away. The Masai were evicted from the whole of Laikipia and their grazing land confiscated. The confiscated lands formed what was called the "White Highlands" which were under the

exclusive use of the Europeans. Their former rightful owners were thrown out and the forests where they obtained firewood and building materials were declared forest reserves.

Before long the newcomers, a privileged minority group of not more than 9,000 Europeans, had the exclusive rights to nearly 17,000 square miles of the country's fertile lands.

In 1915 the Crown Land Ordinance Act was passed. This made all Africans "tenants at the will of the Crown". This meant that Africans no longer had any legal rights to the lands they

occupied. Land title deeds could not be issued to them. The Kikuyu, who were the most affected felt very insecure on the inadequate small pieces of land they occupied. They could be evicted any time

to make room for white settlement. Their future was very unpredictable.

The majority of the African male population, nearly 60%, remained unemployed. The limited land could no longer support them. They wandered aimlessly and became casual labourers in the

towns. Hundreds of Kikuyu families became squatters on their former lands. They provided cheap unskilled labour on which the European farms depended. The majority of the tribe lived in overcrowded

land units which the colonialists called "Native Reserves". Here they were not supposed to grow cash crops or keep grade cattle. They were required to engage purely on subsistence agriculture.. Grown

up African men were referred to as "boys". When called upon they were supposed to give respectable replies; "yes madam" and "Bwana" (Master). This was extended even to employers'

children.

In politics the African had no say whatsoever on how the country was administered. The settler government started indirect rule by introducing a system of paramount chiefs in Kikuyu

country, which never existed before. They were not in any way people's representatives. People regarded them as the white man's stooges who stood by and "let the land go".

The country's political and economic fabric was purely European controlled. The Africans were regarded as number four. Second to the Europeans in the hierarchy were the Asians. The Arabs

came third in this Apartheid form of government. Priorities were given on the basis of colour. An African's black skin hindered him from mixing, eating or travelling with the white skinned dominant

communities. "We are hated because we are black and we are not of the white race", the Africans said.

The colonial government was determined to force the Africans into extinction as a race, beginning with the Kikuyu who occupied much of the land they desired to have. The administration

introduced "slave labour" to consume the energy of the Africans. Men, women and children were forced to dig trenches on the land they occupied.

Likewise European Missionaries introduced the second type of oppression. The early missionaries arrived in the country holding a gun in the right hand and the Bible in the left hand. Their

primary objective was to use their Christian Religion for the pacification of the Africans. They wanted to make the African drunk with religion while his land was being taken away. Missionaries begun

attacking and condemning the African civilization that they found. They started destroying the fabric of society and the very roots on which it was founded. Everything African, their customs and

rites were branded as primitive and heathen.

The Kikuyu customary rite of female circumcision was on top of the agenda. It was described as heathen and barbaric. Kikuyus who refused to denounce the custom were not allowed to pray in

churches nor would circumcised girls be allowed in mission schools.

Polygamy was rejected outright. Those who had married more than one wife and wished to become church members were supposed to denounce and throw away all but one of their

wives.

All tribal songs and dances could not be tolerated. Nor could the customary mode of dress be allowed by the church.

By 1921 the Africans could have no more of it. In that year the first political party in Kenya was formed. It was called the Young Kikuyu Association (YKA). It was headed by a young

Kikuyu, Harry Thuku, a Government telephone operator. The YKA did not last long and in 1922 Harry Thuku organized another party called the East African Association (EAA) whose aim was to unite all

tribes in Kenya to form a strong front to forward African grievances. One of the major grievances was the return of the "stolen lands" and the reduction of the African wages.

Their wages had been cut by nearly a third while their hut tax and poll tax had been increased. The Association protested over the Kipande system. Kipande was a labour registration system where adult

African males were fingerprinted and issued with identification and employment cards. Bearers were required by law to carry these documents wherever they went. Failure to do so resulted in arrest and

imprisonment.

Harry Thuku accused the Europeans of "stealing land" from the Africans and attacked the missionaries for teaching the untrue word of God. He urged the Africans to refuse to work for

Europeans to force them to leave the country. He called on all Africans to discard their kipandes and throw them in front of Government House, Nairobi. The government was afraid of Thuku's political

sentiments. He was arrested on March 15, 1922, detained and deported on charges of being "dangerous to peace and good order". The Association was subsequently banned.

The Association did not die out but continued to operate "underground". In 1926 it emerged in the name of the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA). It called among other things for the African

to be allowed to plant commercial crops such as coffee, elected representation in the Legislative Council and education for the African children. Two years later it started its vernacular newspaper

Muigwithania (Unifier). In 1928 Jomo Kenyatta became its secretary.

The formation of the KCA was followed behind by the sudden emergence in around 1926 of a new Kikuyu political ballad known as Muthirigu. The new song and dance became a political anthem of

the KCA in later years. Its tune had been adopted from coast dances and because of its rousing chorus it became very popular and spread rapidly in Kikuyu land. The song's unlimited number of verses

projected the frustrations, humiliations and sufferings of the Kikuyu caused by the Europeans. By 1930 it began challenging the colonial government and accused the tribal chiefs of being "bribed with

uncircumcised girls so that the land may go".

Other verses in the song were sung in praise of leaders of the KCA. On the whole the song lamented the eroding away of the Kikuyu customs and at the same time looked forward to the day when the white

man would be conquered. The government, fearing the tense atmosphere created among the Kikuyu by the new song banned it in 1930.

The administration accused the dancers of using spears and simis in the dancing. Heavy fines were imposed on anybody found singing it. In any case, the song did not die out completely but

continued as an anthem of resistance. Its rousing chorus lives to this day and the song features prominently in present day tribal dances.

The issue of female circumcision first came into being in 1929 when European missionaries began denouncing it and attempted to eradicate it. Leaders of the KCA protested over their

people's customary rites. The missionaries were obstinate. Majority of the Kikuyu population protested over the mission's act of banning them from schools and churches, and threw their support behind

Jomo Kenyatta and other KCA leaders.

This controversy divided the Kikuyu into two hostile camps each opposing the validity of the other's argument. The two groups played a major role in later years during the State of

Emergency when the war of liberation was at its highest. Each took up arms to fight the other. Those who supported the Church's view became the loyalists and strong opponents of the Mau Mau freedom

fighters.

During this period, a few and very influential Kikuyus signed a church petition expressing their full allegiance and loyalty with the missionaries. They were referred to as kirore (thumb print) i.e. those who signed the document.

Another group of 'die hard' Kikuyu, and by far the majority, refused to sign the document and upheld female circumcision. They accused the missionaries and especially the Church of

Scotland Mission (CSM) of preaching the word of the devil. Those were called the Kikuyu Karing'a (pure Kikuyu).

The Church's struggle with the tribal elders resulted into the formation of the African Church and the African Independent Pentecostal Church. In order to secure education for their

children, the Kikuyu, through a nationwide voluntary collection of funds, established their own schools.

Two groups of schools were started, the Kikuyu Independent Schools Association and the Kikuyu Karing'a Education Association. To supply teachers to their schools the Kenya Teachers'

College was established at Githunguri, in Kiambu. Jomo Kenyatta who led the religious and educational breakaway left the country in 1931 and did not return until 1946.

After gaining some considerable following KCA was declared an illegal society in 1940. Twenty of its leaders were arrested and imprisoned, its headquarters closed and Muigwithania banned.

It was however driven "underground" where it continued to operate during the Second World War period.

The end of the war saw the establishment of more parties namely Kenya African Study Union (KASU) with Harry Thuku as President, followed in 1946 by the Kenya African Union (KAU), among

others. Jomo Kenyatta was elected President of KAU in 1947, shortly after his return. With Kenyatta on the chair many more Africans joined the party than ever before.

All the major tribes were represented and the party leadership could rightly claim to speak on behalf of the entire African population. With the use of its newspaper, Sauti ya Mwafrika (the African

Voice) and other vernacular newspapers the party spread its political gospel far and wide. KAU meetings presided by Kenyatta drew far greater crowds than ever before.

Through Kenyatta's initiative the Independent Churches and schools expanded rapidly. The KCA leaders who had continued to work "underground" during the World War years joined KAU but

continued to retain their own identity. Already they were pessimistic of reaching democratic reforms and African independence through constitutional means and were now considering alternatives.

Their aim and only hope was to establish a strong unity and coherence among the Kikuyu tribe and to use force on the colonial government if other means to the solution of their grievances failed. All

their activities were hidden under the wing of KAU.

In 1947 a very militant group headed by very young men emerged. It was called the Forty Group (Riika ria 40) or "anake a forty". They were the young men who had been circumcised in 1940.

These were ex-servicemen who had fought either in the Burma forest, India or Madagascar during the Second World War. They had returned home with a lot of experience of the outside world. Soon after,

they found themselves without employment and without land. Their European counterparts had been rewarded for their services with big farms in Kenya as retirement benefits.

Men of the "Forty Group" became the most politically militant and committed men. They no longer could accept the government's oppressive measures. They denounced trench digging which was

going on in the "reserves". The Group threatened to take up arms against the government if KAU's demands were not met. Their activities were centred in Nairobi but their following stretched deep into

Nyeri, Fort Hall (Murang'a), Kiambu and the Rift Valley areas.

Samuel Mwangi, the treasurer of the Forty Group gave an indication of what the group was when he said: "The Forty Group is manned by 2,000 men who are ready to tear to pieces anyone who is spoiling their district and revealing their secrets. We have so far done wonders and we shall continue to do much more in the future." ...

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta

Profile

Jomo Kenyatta was born Kamau Wa Ngengi at Ng'enda village, Gatundu Division, Kiambu in 1889. He was the son of Muigai and Wambui.In 1896 his father died and Wambui was inherited by Muigai's younger brother Ngengi.That is the union through which James Muigai, Kamau's half-brother was born. Kamau's mother later returned to her parents where she died. Kamau moved from Ng'enda for Muthiga to live with his grandfather Kingu wa Magana who was a fortune teller and medicine man. He took interest in Agikuyu culture and customs and used to assist his grandfather in the practice of medicine.

http://www.statehousekenya.go.ke/presidents/kenyatta/profile.htm

Uhuru for Kenya

For over 50 years Kenya was regarded as a preserve of the white man. He occupied the rich farmlands while those Africans who did not work for him as houseboys or labourers lived as best they could in the townships or the tribal reserves. Until well after the Second World War, the white man’s privileged position seemed assured. “Uhuru” - freedom for Africans to determine their own political future - appeared to be no more than a fanciful notion. “Any attempt to hand over power to an immature race must be resisted,” warned the influential Electors’ Union of white settlers in 1950. “We are here to stay and the other races must accept that premise with all it implies.” But there were many Africans who refused to accept the premise and some who were prepared to kill Europeans - and fellow-Africans - in their determination to win the coveted prize of Uhuru.

The High God, Mwene-Nyaga, creator of all things, who lived I I on Mount Kenya, seemed wrath I I with the children of Gikuyu, his chosen son, and Mumbi, his son’s wife. For as long as any

Kikuyu elder could remember, the tribe had prospered in the forests around the mountain, turning its slopes into gardens. It was their own world, and they knew no other, until by growth of numbers

the nine clans, descendants of the nine daughters of Gikuyu and Mumbi, needed land beyond the forest. Then they met the Wandorobo hunters, who sold them land, and the cattle-owning, lion-hunting

Masai, who threw them back into the forests and the northern deserts, where only Turkana, Galla and Samburu could survive.

And they met the wandering Red Men who were few but spat fire. Then a plague struck down the people, killing half of their numbers, and they shrank back into the forest.

The elders consulted the spirits of the ancestors. And those versed in magic and divination replied: To those punishments would be added an iron snake, brought by the Red Men. The Red Men multiplied throughout the land and harassed the Masai, driving them south. Then the Red Men began to encroach into the forests, and when the warrior children of Mumbi set on them with ambushes, the Red Men slaughtered them with their terrible weapons and took the land around the forests. The Red Men informed Mumbi’s children that they were now the children of Queen Victoria. And the iron snake puffed up from the coast to Nairobi, “the place of cold winds.”

In that time of tribulation, in the late 19th Century by the Red Men's reckoning, there was bom to Wambui, wife of Muigai, a farmer of Ngenda in Kiambu, a healthy boy who was named Kamau wa

Ngengi. Nobody knows in what year this was: the Kikuyu did not keep records as did the strangers. The boy lived in proximity to nature, learning wood-lore, animal-lore, and the workings of the

spirits in all things. Then one day a pink-faced man named Scott asked permission to set up a mission to teach the new things and certain glad tidings. The boy considered and finally went, in

November, 1909, to the mission school at Thogoto.

It was as Jomo Kenyatta that the world was to know this boy, first as the alleged leader of the Kikuyu-led Mau Mau terrorist movement of the early 1950s, then as the first Prime Minister and

later President of an independent Kenya. To understand Kenyan nationalism it is necessary to understand Kenyatta - and to understand him we must first understand the land in which he was born.

By the time he was baptized into the Scottish Kirk in 1914, the Kikuyu population was growing and many of the tribesmen had to go to work for the bwanas who were farming around Kiambu. The Kikuyu

were one of a dozen “new caught peoples, half devil and half child” who were taken under British suzerainty in 1895 when the Imperial British East Africa Company (I.B.E.A.C.) could no longer manage

on its own. Uganda had been made a British protectorate the previous year and the government now decided to go ahead with its controversial scheme to build a railway from the coast to Lake Victoria.

Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister, believed that without the railway Uganda would be lost, with dreadful consequences for the Suez Canal, and thus for India.

George Curzon, Salisbury’s foreign affairs spokesman in the House of Commons, told M.P.s that the protectorate in Uganda was “absurd” without a railway to the coast, adding that if the British did

not build a line to the lake the Germans certainly would. (They had, in fact, already started one.) French ambitions were also feared and advocates of a British rail line stressed its decisive

military importance.

George Whitehouse, a railway engineer, arrived in Mombasa on December 11, 1895, to take charge of the project and in 1898 the iron snake’s tracks began to move inland. In 1899 they reached

Nairobi, where the Kikuyu disputed the way with the advance parties and were machine-gunned. The Nandi, too, had tried to stop its construction, causing a fatal accident, and were also machine-

gunned. Even the lions of Tsavo tried to stop it and, after eating 28 Indian coolies and a white assistant, they were shot by an irate colonel of the Indian Army. In 1902 the line was at last

completed; what Henry Labouchere, the Liberal antiimperialist, called the “lunatic express” could run from Mombasa to Kisumu (connecting with lake steamers), a distance of 657 miles.

The building of the railway contributed powerfully to the “pacification” of the local tribes. A sullen peace, punctuated from time to time by futile risings, pre vailed in the area known

as British East Africa. The tribes were ruled by Britain through their ownchiefs, of whom the mightiest was the Kabaka of Buganda The same pattern of rule was imposed on the Kikuyu and, when the

tribe tried b explain that it had no chiefs but was organized by age groups depending upon seniority, chiefs were obligingly appointee - and paid - by the British.

But the pacification of the tribes provided no freight for the railway and, to the Treasury’s horror, losses mounted. Lore Delamere, a hot-tempered landowner from Cheshire with a love for

the wild open spaces of Africa, proposed a solution The highlands on the fringe of the Kikuyu forests were suitable for farming am ranching. Delamere envisaged the English farming the highlands, the

Indians (ex coolies who built the railway) populating the coasts, and the Africans hewing wood and drawing water for both. The railway would pay its way by carrying the produce.

Delamere and his friends found; temporary ally in Sir Charles Eliot appointed Commissioner of the East African Protectorate in 1901. Eliot backed Dclamere’s demand for land and decided to encourage

as many white settlers a possible. The Foreign Office was so desperate under the hounding of the Treasury that it considered encouraging Finns and Zionists to emigrate, but in the end enough Britons

and South African moved in to pay for the trains.

Land seemed plentiful, but so, too, did the Masai. Most of the settlers urged that the tribe be placed in a reserve, thus re-moving the last obstacles to European occupation of the

Naivasha region and also providing the settlers with a convenient pool of African labour. Eliot however, adamantly opposed a Masai reserve. The tribe, he maintained, needed contact with Europeans in

order to become “civilized.” Overruled by the Foreign Office, Eliot resigned in 1904. Hi successor, Sir Donald Stewart, immediately signed a treaty with the Masai which granted them two

reserves. In 1906 four more reserves in Kenya were created for the Kikuyu, Kitui, Kikumbuliu and Ulu tribes.

The settlers had an insatiable appetite for land, even if they could not use it. And at first, they could not. Delamere tried European crops: cereals, legumes, roots, fruits; with

monotonous regularity they failed, destroyed by pests and diseases. Other noblemen followed him, sinking fortunes into taming the Masai grassland and the red soil of Kikuyu forest ridges. In the end

they succeeded, backed by 20th-Century technology - and the indispensable labour of the Africans. But first sufficient African labour had to be enticed out of the forests. The authorities imposed hut

and poll taxes which the blacks could pay only by working on the white men’s farms.

The settlers themselves demanded legalized methods of compulsion and the right to flog their black workers. The Colonial Office, which in 1905 took over the administration of Kenya from the Foreign

Office, resisted the settler demands, but did agree to prohibit Africans from growing cash crops such as coffee, lest they become rich enough to refuse work on the white farms.

From the beginning, the settlers saw themselves winning self-government or seizing it, like the Americans. By 1914, they had four members - appointed, not elected - in the Governor’s

Legislative Council, whereas the Indians had one and the Africans none.

The whites also had powerful friends in London and some could speak for Kenya in the House of Lords. Governors had to compromise between their duty to uphold the principle of Colonial Office

“trusteeship” and the ceaseless European demands for more land, more power, more cheap labour. The officials who administered the “reserves” were supposed to be independent of the settlers; in

practice, they were themselves part of settler society and many retired to farms in the highlands. So even with self-government far off, the colony was largely managed in the interests of the white

highlanders who, admittedly, produced most of the revenue.

Until the early 1920s this aggressive, powerful and uninhibitedly racialist group saw the Indian shop-owning and commercial community, backed by the India Office, as its greatest rival.

Having excluded the Asians from landownership, the whites sought also to restrict their political influence. Intelligent, educated and outnumbering Europeans by four to one, the Indians formed their

own political association and quickly turned to the Africans for allies. In 1920, the year in which the protectorate became Kenya Colony, the Kikuyu chiefs also formed an association to prevent the

European land-grab and the growth of semi-forced labour.

In the following year Harry Thuku, a telephone operator earning £4 a month, formed the Young Kikuyu Association to protest against the doubling of the hut tax and to demand the abolition of kipande,

restrictive pass laws.

Thuku received support from Desai, an Indian leader and editor of the journal, East African Chronicle, but was sacked for his political presumption and eventually deported to the desert

region of the north as a danger to good order. The Nairobi Africans protested and on March 16, 1922, a number were shot down, much as the Indians were at Amritsar, while cheering settlers looked

on.

The settlers felt that the Africans had been taught a valuable lesson. Indeed, they had. But the lesson they learned was that African political organization was possible and could get results. The

Colonial Office declared that African interests were paramount and, though this principle was later watered down, it was to remain the basis of British policy in Kenya.

Johnstone (his baptismal Chris tian name) Kenyatta was living at this time in some style in Nairobi. His education and training at Thogoto mission school had proved useful and in 1918 he

had taken lodgings at Kilimani, near Nairobi, attended evening classes and finally obtained a job as a meter-reader for the municipal water department. Entering into the conviviality’s of the Indian

quarter, he became a well-known figure, cycling round the city in his slouch hat, breeches and settler-style bush jacket.

‘But he was soon in trouble with his missionary friends, white and black. Not only was he drinking intoxicants, but his intended wife, Grace Wahu, became pregnant by him. At first, Kenyatta defied

the Kirk, then bowed to its tribal and spiritual authority. Kenyatta was also listening to much political talk. Sir Edward Grigg, who became Governor in 1925, and Leo Amery, the new imperialist at

the Colonial Office, were considering asettler-ruled federation of Kenya Tanganyika and Uganda. When, in 1927 the Hilton Young Commission was set up to discuss the proposed union, and the Asians

opposed it, the Africans saw a chance of publicizing their own grievances over land and the repressive laws that restricted their liberty and weighed them with taxation.

Thuku, however, was still in exile and a successor was needed to plead the African cause with the whites. The Kikuyu Central Association had emerged in 1925, after a short break in the

activities of the Young Kikuyu Association following Thuku’s arrest; it carried or his policies and he was its chairman. In 1927 Kenyatta was persuaded to leave his well-paid job and become the

organizing secretary, and editor of Muigwithania the first African-owned journal. Written in the Kikuyu vernacular, it began to pull forward Kikuyu demands for education abolition of the hut tax on

women and restitution of stolen land. Its articles skilfully and bafflingly allusive, but within the press laws, earned Kenyatta the official label of a “dangerous agitator.’ When the Hilton Young

Commission met the settlers’ demand for more land or the “delimitation of boundaries” was first on the agenda, and Kenyatta gave evidence When the commission moved to London Kenyatta insisted on

following it.

So far as Kikuyu aims were concerned at the time, the move was a waste of money; but it did enable Kenyatta to create a base in London from which he would win sympathy and support for the Africans and develop his own education and career. He failed, however, to get an interview with the Colonial Office, although the incoming Labour government of 1929 rebuffed settler hopes of responsible government for whites only. Grigg was in London and Kenyatta met him unofficially. The young nationalist agitator made a not unfavourable impression on the Governor though Grigg took the precaution of setting the police Special Branch on to him. More importantly Kenyatta made contact with left-win… continued by Roy Lewis

Nairobi Africans peaceful protests March 16th 1922

During the colonial period, the white men killing of Africans was some sort of a favourite sport. There were some many cases but some of the notorious ones included the shooting of 21 unarmed

Africans outside the Norfolk Hotel in 1922.

Before and after the mass killing, it was a common feature for a white settler having an evening drink at the terraces of the Norfolk or the Stanley Hotel to draw his rifle and aim at an African passing by in the distance.

TRIP DOWN MEMORY LANE

Celebrating our African historical personalities, discoveries, achievements and eras as proud people with rich culture, traditions and enlightenment spanning many years.

PHOTOS: Inside the house where President Uhuru was conceived in 1961

MZEE JOMO KENYATTA IN MOMBASA, KENYA DEC 12TH, 1963

Connecting with Kenyan history.

Here is the person who designed the Kenyan National flag, the coat of arms, and the Presidential standard just before Kenya was granted internal rule on 1st June, 1963.

His late mother worked late into the night to work and complete making the 12 flags that were to be flown on the 12 ministerial cars.

M.A.Sheikh,MA,ARB Chartered Architect & Urban Designer who migrated to the UK in 1973,is now practicing in London, was a civil Servant in Kenya and worked closely with Joseph Murumbi and Robert

Ouko when he was assigned the task of designing the various flags, including designs for a number of medals. More photos and old newspapers cuttings will be posted later.

Some more photos of the art work undertaken by M.A.Sheikh. Most were finally approved after the desired changes were incorporated. The drawings of Lions in the original design were not accepted and the sketches of real African lions were incorporated. Since cockerel was KANU's symbol, KADU supporters used the Panga (Matchet) as their symbol and were their weapon for slaughtering the Jogoo! Sheikh used his own creativity and replaced it with an axe which was well received and incorporated in the final design.

Click below on photo to enlarge

The Right Rev. Thomas Johnson Kuto Kalume

The Right Rev. Thomas Johnson Kuto Kalume is the composer and co-producer of “Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu“, the Kenyan national anthem, which was recorded in September 1963 and inaugurated at Uhuru Gardens on December 12, 1963 during Kenya’s independence celebrations.