Nubians

STATELESSNESS

Kenyan Nubians have been defined as stateless people because their identity is questioned. They are

without doubt one of the country’s most invisible and under-represented communities –economically, socially, politically and culturally. This is because they have been silent victims of discrimination, exclusion and violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms for as

long as they have been in Kenya.

http://www.fmreview.org/FMRpdfs/FMR32/19-20.pdf

The origin of the name Nubia is obscure. Some have linked it to nwb, the ancient Egyptian word for gold. Others connect it with the term Noubades, the Greek name for people who moved into northern Nubia sometime in the 4th century AD. Nubians developed alphabetic writing systems around 200 BC during the Meroitic period. The Meroitic language is still not understood well enough to read more than words and phrases, but much documentation on Meroitic Nubia can be found in the art and literature of Greece and Rome, whose empires touched on the borders of Nubia after 330 BC.

https://oi.uchicago.edu/museum-exhibits/history-ancient-nubiaOLD

http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/moving-walls/19/kenyas-nubians-then-now

Nubians in Uganda

WHO REALLY ARE THE NUBIS OR NUBIANS IN UGANDA

WHO ARE REALLY THE NUBIS OR NUBIANS SO CALLED IN UGANDA?

http://www.africaspeaks.com/reasoning/index.php?topic=6262.0;wap2

Nubians by Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

How the Nubians provided the foundation for the Kenyan and Ugandan armies, and how they ended up in small towns.

The Anglo-German agreement of 1890 designated Uganda as a British sphere of influence.

But since the British government did not want to be directly involved in the administration of Uganda, it gave that mandate to Imperial British East African Company (IBEAC) under Captain Lugard.

Lugard arrived in Kampala in December 1890, his small army consisted mainly of Sudanese soldiers , he had recruited in Cairo.

From the beginning the IBEAC suffered from a chronic shortage of funds, but Lugard was desperate for more soldiers. He was, therefore looking for soldiers who would live off the land and not cost the IBEAC anything.

At the same time he was looking for best soldiery material in Africa". So he hoped to find them, at Kavalli in Equatoria province along the upper reaches of West Nile in the present day South Sudan.

He arrived at Kavalli in September 1891, right at the time when a large part of Fadl el Mula's under Salim Bey group was arriving there.

At Kavalli's, Lugard found a large group of undisciplined militants, addicted to strong liquor', and with a huge number of dependants. He was ,however, impressed by their prowess and loyalty to Egypt. In the end, he managed to recruit so fine a body of men among them for IBEAC Company's service.The number that went into Uganda with him was slightly more than 8000.

Selim Bey, firmly in charge of the "Egyptian army", agreed to join Lugard at IBEAC in Uganda on condition that the Khedive of Egypt would approve it (which he did one year later), and that he himself would be the commanding officer, taking orders from Lugard only.

On 5 October, 1891, Lugard, Bey and the soldiers and their families left Kavalli's in three groups, at intervals of one day in order not to create queues too long to manage for the 600 miles trip.

They walked only a few hours in the morning to avoid the heat. But even in three groups, the journey was difficult. The columns were seven miles long, they were attacked by local people, and children drowned.

Along the way from Kavalli's to Kampala, a line of forts was built at strategic places to keep the stubborn kingdom of Bunyoro under control. In each fort Lugard left a number of Nubian soldiers with their dependents, usually around 2000 people, under the command of a reliable Sudanese officer.

They were to grow their own food, but they were also allowed (if not encouraged) to raid into Bunyoro for food

Towards the end of 1891. Lugard and Selim Bey arrived in Kampala with the remaining soldiers and dependents.

However with Lugard and Bey away, the soldiers left behind lost their discipline . They not only raided Bunyoro, but also created havoc in the areas they were supposed to protect.

They continued their militant life as they had done in the stations in Equatorin as the Egyptian army. They took wives, concubines and servants (voluntarily or involuntarily) from the local tribes, and looted from their neighbours.

The King of Toro sent messages to Lugard in Kampala begging him to protect his people from the "pitiless Sudanese".

In the Sudanese's defence it is worth noting what Furley said about their behaviour. "It's in fact the traditional African system of warfare, and apparently the Swahili soldiers' "reputation amongst the local inhabitants does not appear to have been very much better than that of the Sudanese."

Lugard was heavily criticised for his decision to bring the Sudanese (Nubian) soldiers to Uganda, certainly when the rumour was going around that the Sudanese had made a pact with other Muslims groups to take power in Buganda and establish a Muslim state, or even link up with the Mahdists and other Arabs.

The rivalry between Muslim, Protestant and Roman Catholic groups in Buganda had caused civil war in the Kingdom between 1885 and 1890. However in 1890, Kabaka Mwanga supported by Christians regained control forcing the "Mohammedans' to flee into Bunyoro, from where they continued raiding into Buganda.

After a second Mohammedan war (1891) in which the Muslims were beaten by a force led by Lugard, they accepted a peace offer in which they got three provinces to themselves; nevertheless, tension remained high.

On 1 April 1893, with the IBEAC bankrupt, Britain took over the administration of Uganda. The Government Commissioner Sir Portal decided to abandon the western forts along the Toro-Bunyoro border and to bring the Sudanese soldiers to Buganda and Kampala as regular troops, to replace the more expensive and less efficient Zanzibari troops.

However there was growing suspicion of the Sudanese soldiers plotting to support Muslim elements in the Buganda Kingdom to take over power.

As a result In June 1893, when there was a serious threat for another Mohammedan revolt in Buganda, the Sudanese troops were quickly disarmed, and Selim Bey, who had continued to play an important role as commander of the Sudanese, was arrested and charged with mutinous behaviour".

Plans were consequently made to deport him to Mombasa on retirement pay." Unfortunately he died in Naivasha, on his way to the coast. Some older Nubians in Kibera still tell mythological accounts that Lake Naivasha sprung up on the spot where Selim Bey died.

Nevertheless, the growing strength of the Bunyoro kingdom seemed to pose a serious threat to Buganda Kingdom which was an outpost of the British. In early 1894, a large force, comprising of 400 Sudanese soldiers together with eight Europeans and 15,000 Baganda spearmen, occupied Bunyoro.

This was the first time the Sudanese soldiers were proving their worthiness as soldiers of the King of England. Even though they never engaged in serious battle with the forces of King Kabarega of Bunyoro, they were praised for their discipline and it was claimed, they were "reliable, loyal and a terror to their enemies."

The British were now anxious to enlist the Sudanese troops as 'regulars' and even recruit more of them, because many Sudanese soldiers were now, too old for active service or even garrison duties, and about to retire.

Furthermore, the Sudanese remained the cheapest soldiers, and Uganda could not afford anything else. So, when in early 1894 a large group of Sudanese soldiers were reported to be trespassing into British territory from Belgian Congo, Captain Thruston was quickly sent to bring them all into Uganda.

It turned out these people were part of the original Fadl el Mula group that served with the Belgians of the Congo Free State for about two years. In January 1894, after they had split up in two groups on their way to Wadelai (to claim the area for the Belgians), Fadl el Mula's group was ambushed and annihilated by the Mahdists.

The second group, of about 350 soldiers with a huge number of dependants around 10,000, managed to reach Wadelai and, in search of food, continued further south along Lake Albert. This was how they ended up straying into Uganda.

Here they were approached by Captain Thruston, who convinced them to enlist with the British in Uganda. Like before with Lugard, they went in long columns, walking for many hours. More than half of the group's dependants (slaves, women, children) disappeared (deserted or died) during the journey and at arrival in Kampala the number of dependants had reduced from 10,000 to 3000. were counted.

These Sudanese marked the second group of "East African Nubians to enter East Africa as military men.

On 18 June 1894 Buganda was declared the Uganda Protectorate. The area excluded Bunyoro, Toro and Ankole, but extended to the east to include Naivasha in what is now Kenya. The area between Naivasha and the coast had for long remained a no-man's land, considered desolate and useless.

However, the accessibility of the new Protectorate became an issue: the road north through Sudan was closed due to the Mahdists presence and the long distance to the coast (800 miles) through inhospitable area would require 3 to 4 months on foot.

As it became clear that a railway from Kampala to Mombasa on the coast would solve that problem of inaccessibility, the "no man's land", including the area up to the Juba River in Somalia, was, in June 1895, declared the East Africa Protectorate, later becoming Kenya.

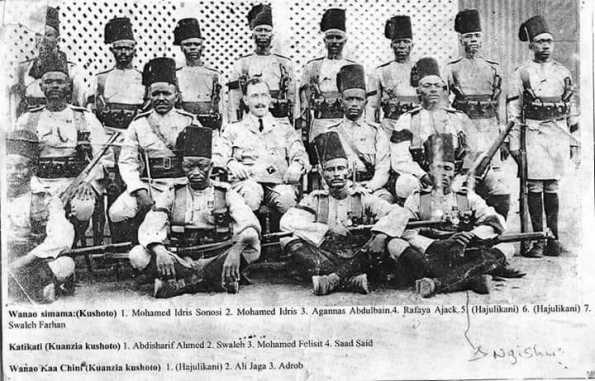

On 1 September 1895, the official Ugandan army, the Uganda Rifles, was established and was made up almost entirely of Sudanese soldiers. They initially signed a 12 year contract and were organised in 10 companies which were under the command of European officers. In July 1896, the Uganda Protectorate was extended to include Bunyoro, Toro, Ankole and Busoga, covering the area that is now Uganda, and including the area Naivasha.

The following year, 1897, was a busy year for the Sudanese soldiers: they were almost continuously on the road, marching to and fighting in different places. First in Toro, then Kavirondo north of Lake Victoria, next a punitive expedition against the Nandi (Kenya), then back to Buddu in Uganda. This started to create problems.

After the campaign in Buddu, in September 1897, some Sudanese companies stationed at Ngare Nyuki, near Eldama Ravine mutinied demanding better pay and clothes. The Sudanese were paid only four Rupees/month (a private), even lower than the carriers, who eamed 10-12 Rupees. Other complaints were that they were insufficiently fed, they were not allowed to take their wives and children on expeditions , their officers did not speak Arabic so they did not understand them, and that they were treated like donkeys.

The mutineers marched towards Uganda, looting the military stations and villages along the way, killing people, destroying bridges, and stealing livestock and whatever else they could carry. They tried to convince (Sudanese) soldiers at Mumias to join the mutiny, but most remained loyal to the British.

The mutineers, now around 500 men, occupied the garrison fort at Luba's (near Jinja, Uganda). Surrounded by British troops, negotiations and some clashes took place, with heavy losses on both sides.

At this point most mutineers were ready to give up and surrender, but the Sudanese officers, fearing to be held responsible for the mutiny, executed some British officers they had taken prisoner, knowing that from then on the mutineers could no longer count on mercy.

In this way they implicated all mutineers, expecting them to continue to fight till the end. They also lashed and locked up anyone hinting at surrendering. After 3 months of siege, in early January 1898, the mutineers broke out of the fort and fled northwards to Lake Kyoga.

Some battles took place in which the mutineers were defeated: many were killed and the rest dispersed, while women and children, as well as belongings were left behind. Nine ringleaders were executed, while a large number of captured soldiers was sacked and a smaller number acquitted. The remaining mutineers fled further north, causing some trouble over the years.

They were finally defeated in 1901 during the so-called "Lango expedition", the punitive expedition against the remaining mutineers

The army returned with 1485 prisoners.

After the mutiny. the Uganda Rifles were reorganised: the number of Sudanese soldiers was reduced (but still at least 75%) and they were to be gradually replaced by Swahilis, Somalis, Indians and native Ugandan people. Salaries were increased to 18 from 10 Rupees per month.

In 1901, all the armies of the regional British Protectorates were organised into battalions of one colonial army. On 1 January 1902 the "King's African Rifles" (KAR) was born.

It was made up of 4th (Uganda) battalion KAR, and the 3rd ( British East Africa later known as Kenya) battalion KAR. Both battalions had a large number of Sudanese soldiers and provided the foundation for the present day Kenya and Uganda armies

There was enough to do in those early years for the Sudanese soldiers as British rule met resistance in almost every comer of the Protectorates. They were used in punitive actions against the Nandi (1895-1906), the Kikuyu and Embu (1904-1907), and in 1909-10 in Somaliland against the "Mad Mulla. But Much of the work concerned securing the Uganda Road (from Mombasa to Nairobi to Kampala) for trade caravans, escorting mail and food caravans, and protection of the construction of the railway.

There were also military actions against the Giriama, Taita, Kamba, Kisii and Elgeyo tribes. In 1902, after the railway had reached Port Florence (now Kisumu). the Uganda Protectorate ceded its eastern province to the neighbouring East Africa Protectorate. for the purpose of having the area crossed by the railway under only one administration. The new East Africa Protectorate territory consisted more or less of present-day Kenya plus the area further cast, up to the Juba River in Somaliland. Some 250 Sudanese soldiers were subsequently in 1904) transferred from KAR 4" battalion (Uganda) to the 3 battalion British East Africa(later Kenya).

It was the habit in those days,to allocate some land to the soldiers to cultivate and grow food for their families. Retired and demobilised soldiers were also given land near the barracks.

Like the Egyptians before them, the British used the Sudanese soldiers' sons for the recruitment of new soldiers, and found it very convenient to have a reserve force of veterans close at hand in case they needed experienced soldiers on short notice.

Moreover, the East African armies never had much money, and the protectorates tried to keep KAR as cheap as possible, so there was probably no money for pensions, giving land was a much cheaper option, and remained for a long time the KAR soldiers' only pension.

Locally recruited soldiers usually returned to their rural home after leaving active service, but in East Africa, these Sudanese "detribalised" veterans had nowhere to go. They could not go back to their original communities in Sudan.

Being so inextricably tied to the military culture and life, they settled permanently near or next to the forts, stations or barracks, with their families and dependents. Sudanese (Nubi) villages were established in Uganda, Somalia and Kenya, wherever the army had more permanent bases.

In Kenya, they were established in Kiambu, Mazeras, Machakos, Kibigori, Kibos, Kisii, Kisumu, Mumias, Eldama Ravine and Nairobi, amongst others. Most of these places had been forts or barracks along the Uganda Road or the railway

Kibra, in Nairobi, became the main Nubi settlement in Kenya, being next to the main KAR barracks. Most of the Sudanese soldiers who served in the KAR in those days, at some point, passed through Nairobi, and were based for a short or longer time at the KAR barracks. Many of them would ultimately settle in Kibera, after retirement or demobilisation.

EXERPTS FROM THE BOOK 'KIBRA IS OUR BLOOD " BY THOMAS PARSONS

ESTABLISHMENT OF KIBRA PART 1

The Establishment of Kibra, 1904-1928

Before the First World War, the numbers of askaris (soldiers) discharged from the KAR were not large enough to constitute a problem for the civil administration. The Kenyan government assumed locally

recruited soldiers would simply return to their reserves, where they would be cared for and supported by extended family networks. The nubians , however, were not natives of Kenya (or the East Africa

Protectorate, as it was then known). As a matter of security, district officers encouraged them to settle near government stations in order to provide a form of military reserve should their services

be needed on short notice. Little thought was given to the long-term ramifications of this policy. The expansion of the KAR from six to twenty-two battalions during World War I produced a community

of "detribalized" askaris who, because of their long military service, or conversion to Islam, either could not, or would not, return to their homes in the "Native reserves." In the case of the

Nubians, their Islamic faith and remote origins in the Sudan qualified them for "detribalized" status. John Ainsworth, writing as the provincial commissioner of Nyanza Province in 1916, was one of

the first colonial administrators to become concerned with the "problem." He worried that "detribalized" askaris would degenerate into a class of "professional beggars and hangers on" after spending

their disability or war gratuities, and proposed hiring them as caretakers, headmen or watchmen for European farms and businesses. In certain limited cases, he envisioned land grants to "detribalized

native" veterans or their widows.[5] Since they were not part of a "traditional" African community, the Nubians were not assigned a native reserve," nor were they under the jurisdiction of the

"native tribunals." As these mechanisms of indirect rule and "tribal law" were unworkable, Ainsworth proposed settling the Nubians near administrative stations where they would pay a nominal rent,

and be supervised by district commissioners (DCs) with the power to evict them if they became unruly. Ainsworth was opposed to making the settlements too large because he correctly foresaw that they

had the potential to become ungovernable permanent communities: "The fewer the number of detribalized people we are required to deal with eventually the better." Thus, he proposed a scheme where only

disabled veterans would have the security of rent-free tenure, while healthy men and their families would become a class of rent- and tax-paying tenants residing at the will of the colonial state,

subject to eviction at any time.[6] It is against this background that Kibra must be considered. In 1911, the KAR's training ground was informally settled by survivors and widows of the Nubian

askaris of "B" and "C" Companies of 3 KAR. They were soon joined by other nubian veterans who had been evicted from their settlements near Machakos and Kiambu that same year. Kibra's proximity to the

3 KAR barracks appears to have been the main factor in drawing the Nubians to the area. By 1912, the KAR officially sanctioned their residency by permitting 291 Sudanese askaris to live in what came

to be known as "the KAR shambas." Only veterans with more than twelve years of service were eligible for "shamba passes," which allowed them to live rent free as a form of unofficial pension (those

with nine years service were already eligible for a lifetime exemption from either the hut or poll tax).

During the First World War, many nubian veterans of Kibra returned to active service, and in 1918, the colonial government officially gazetted the area as a Military Reserve.[7] Yet the Sudanese

tenure in the location was far from secure. By the end of the war, it had become clear that the land on which Kibra was located would be too valuable to leave to the veterans, and Nairobi's European

residents were already beginning to complain about the crime and disorder that invariably sprang from having an army base so close to the city center. By 1919, the government developed plans to move

the 3 KAR lines roughly twenty miles south of Nairobi to Mbagathi. The 4,198 acre "Reserve Shamba" (Kibera) was to be relocated to a smaller 2,000-acre area in Fort Hall district, "where the KAR

exaskaris may be allowed to live in perpetuity in place of the present reserve."[8] Although the plan floundered due to its cost, it marks the first of many attempts by the colonial regime to remove

the Nubian veterans to a more remote region where they could be more easily controlled. By the 1920's, Kibra's reputation grew as a site for receiving stolen property and the illegal distillation of

what became known as "Nubian Gin" or "Arak." In 1926, Kenya's colonial secretary, G.A.S. Northcote, expressed concern that former African government employees "squatting" in urban areas would "tend

to crowd out towns and produce a shiftless population, utilising ground which is required for other purposes."[9] It is interesting to compare the resiliency of Kibra to the fate of Kileleshwa, a

neighborhood of Nairobi that is now solidly upper-class, but in the 1920's was another informal settlement of "detribalized Natives." While Kibra was under the jurisdiction of the KAR and almost

exclusively Sudanese, in 1926, Kileleshwa's population of 709 souls was a much more heterogeneous mix, which included substantial numbers of Kikuyu, Kamba, and other Africans from as far away as

Uganda and Tanganyika. Of the 264 registered plot holders, only sixteen were veterans of the KAR. Without the protection of military patronage, the African residents of Kileleshwa could do little to

stand up to their influential European neighbors, who complained that the Native settlement was a breeding ground for crime and disease. In 1927, the loation's entire population was evicted forcibly

under the "Resident Natives Ordinance."[10] Kibra, like Kileleshwa, was also deemed too valuable and too near European settlement to be left to Africans, but in Kibra the military connections of the

Nubians safeguarded them from summary expulsion. Unfortunately for the Sudanese, the King's African Rifles was a fickle and unreliable patron. Since KAR officers were limited to a maximum of two

tours of two to three years, officers who understood and respected them were gradually replaced by new men who knew nothing of their past exploits. Moreover, the contraction of the KAR during the

lean economic years between the two World Wars meant that the army saw the continued military administration of Kibera as an unjustifiable drain of manpower and funding. In 1926, the original KAR

residency passes of the Nubians were withdrawn by order of the commander of 3 KAR. By 1928, the Kenyan government and the KAR agreed that no more permits would be issued, and the plots of deceased

residents would not be reallocated to other Sudanese veterans. Kenya's senior commissioners, meeting in the same year, decided that "detribalized natives squatting on the KAR Reserve" had no claim to

special privileges. They optimistically declared that the Nubians would be moved when the operational headquarters and barracks of 3 KAR was shifted from Nairobi to Meru in 1928, thereby rendering

further military supervision of the community impossible.[11] Thus, the Kiberan Sudanese were quietly placed under civil administration for the first time during their residency in Kenya

Source: kibra is our blood by Thomas Parsons

Untold Nubian Stories

https://www.facebook.com/Untold-Nubian-Stories-108375384775054