When did Maasai name Enkare Nyrobi, which means "a place of cold waters," change to current name "Nairobi"?

The new settlement was named after the Maasai name Enkare Nyrobi, which means "a place of cold waters," although there was no permanent African settlement since the place was grazing land and a livestock watering point. In 1896, a small transport depot was established at the site to keep provisions for oxen and mules.

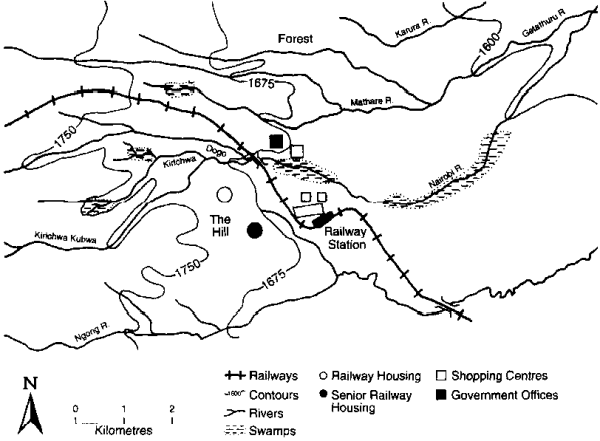

In October 1898, Arthur Frederick Church, a 30 year old assistant railway engineer was dispatched by George Whitehouse, Uganda Railways Chief Engineer, to provide a town layout for the railway depot at ‘Nyrobi’.

From the railhead, Church planned two streets just wide enough for turning three axle oxcart wagons. These would become Victoria Street (today's Tom Mboya street) and Station Road renamed Government Road in 1901 after the government took control of the town (Moi Avenue).

Off Station Road, he planned ten avenues along which houses for subordinates grade railway men would be sited. Along the rise which bordered the flat land, referred to us “The Hill “, Church sketched in a half-dozen sites for upper-grade houses to be accepted by senior railway men.

Along Victoria Street, Church marked out thirteen commercial plots, which be called ‘the European Bazaar' and, away in the distance, he cited the Asian trading area now called Biashara Street.

Needless to say Church's plans were based on railway requirements, not for any civic convenience and on 30th November, 1898, his

master plan for the layout of Nyrobi was approved by George Whitehouse and dispatched to London . The spelling of ‘Nyrobi’ was changed to ‘Nairobi’ on the instructions of Whitehouse on 3rd

Oct 1899 (By Stephen Mills & Brian Yonge).

Recollections by Grace Udall (Mrs Wilkinson)

When we came to East Africa in 1908 we were rowed ashore in little boats from our ship, then we scrambled with our luggage on to trolleys which were pushed along the track by Africans, singing on the downhill stretches and puffing and grunting on the uphill bits. Thus we arrived in Mombasa.

In the train we found ourselves covered in layers and layers of red dust as we slowly chugged our way up country, climbing steadily as the engine gobbled up tons and tons of wood fuel.

It seemed as if the whole of Nairobi had come to the station to meet the train. The hustle and bustle of white-robed people shouting at the tops of their voices, the rickshaw men grabbing your luggage and making off with it. the great Ali Khan with his riding boots and long whip there to take Government officials in his open wagon drawn by a span of mules - all this made a colourful and exciting stage in our journey. We hired two rickshaws and trotted off along the dirt road, with huge gum trees on either side, also a few corrugated iron buildings, and more than a few ruts in the way. This was Government Road (now Moi Avenue I. After what seemed hours we arrived at our new home in Second Avenue. Parklands, a small corrugated iron house on stilts. Three Africans greeted us. and so began our life in a new and raw land.

When we went to visit friends for afternoon tea, my brother and I were dressed up in white starched cotton with lace edging. Off we set, often with the sun blazing straight into our eyes, and as we grew hotter and hotter we dripped all over our beautiful white dresses. The rickshaw men were dressed up too in their ‘livery’. Each, household vied with the next in rigging out its rickshaw team.

My father had a bicycle, and when the telephone failed between Nairobi ar.d Ruiru he would set off at night to cycle the 20 miles there and back, with several papyrus swamps on the way, where hippos and crocodiles wandered across the road. Once, when he got to Ruiru, he found the water no longer running into the power station; a hippo had been sucked broadside across the grille above the intake and got stuck. Eventually it had to be shot, and then a long wait occurred until it became bloated and so water-borne, and was ignominiously towed away.

One year the rains were long and heavy and the roads got worse and worse. Government Road in particular had great potholes in it. The Public Works Department set to work to repair it, digging up long stretches. Then they disappeared, and the road became almost impassable. My father and several other citizens went into the town one night and under cover of darkness planted the road up with banana trees, cabbages and sugar-cane, to the amusement of all next morning. The PWD came and repaired the road soon after.

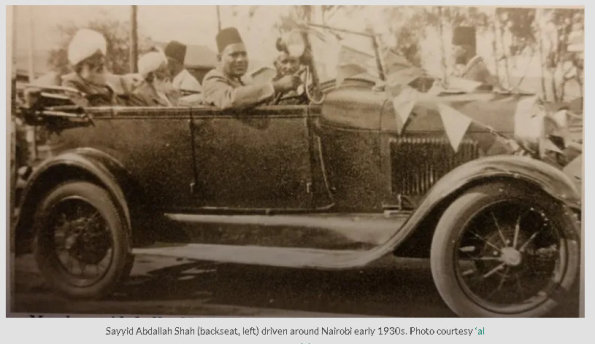

A colourful ceremony which took place in those early

days was the weighing of the Aga Khan in gold at the Aga Khan Club opposite the City Park. Everyone wore gorgeous saris and turbans. The Aga Khan, a portly gentleman, sat on a huge weighing scale,

and bars of gold were added on the opposite side until very slowly the scale lifted him off the ground, when a big cheer went up. I remember dancing at the ball held in the evening, where the Begum

wore a sari with real diamonds scattered over it.

The City Park, which was beautifully laid out with flowering trees and plants and green lawns, was formally opened by the Duke and Duchess of York, who were on a visit to Nairobi, while my father was

Mayor. It was a great day.

Masaai Place and Names

BEFORE the Kenya Highlands became a whiteman’s country; the Masaai roved the grasslands herding cattle and fighting with neighbouring tribes. Now, the Masaai are confined to especially

reserved areas; but they have left in their wake a legacy of pleasant sounding place- names which mark the regions they once occupied.

No doubt it is common knowledge that the word Kenya itself is of Masaai origin— meaning a mist—Ngop de ero-Kenya, the land of morning mists, very aptly describes the Kenya Highlands especially those parts above 7,000 feet. Nairobi too is a Masaai word coming from the root Oirobi. Nairobi or Noirobi is the feminine form, Lairobi or Oleirobi is the masculine.

Often it is found with its noun as for example Ngare- Nairobi. I find it hard to believe that in the case of Kenya’s capital the cold refers to the climate; though the older towns’ folks do say that “way back” it used to be much colder.

While still on the subject of Nairobi it is most fitting that the houses of eminent Nairobi practitioners should adorn Lenana Road which is named after one of the famous Masaai medicine

men.

In Masaailand itself it is safe to say that the names are of Masai origin. Elsewhere owing to the similarity of language of many of the neighbouring Hamitic tribes—a place-name which looks as though it might be of Masaai origin need not necessarily be so. It requires local knowledge to give a definite ruling.

However, a brief review of some of the most common place- names in Masaailand, should give those interested clues to the meanings of places of Masaai origin in other

localities.

Oldonyo is the Masaai name for a mountain.

Oldonyo-Sambu means the striped mountain.

Oldonyo-Sapuk means the big (literally fat) mountain.

Oldonyo-Keri means the speckled mountain, the Masaai name for Mount Kenya.

Oldonyo L’Engai, the Mountain of God, is the Masaai name for the active volcano in the Tanganyika section of the Great Rift Valley (south of Lake Natron) which last erupted in 1940. (See

illustration.)

Oldonyo Aibor, the white mountain, is the Masaai name for Kilimanjaro.

Oldonyo Orok, the black mountain, is the Masaai name for Mount Meru, near Arusha. There are several other mountains of that name in Kenya.

Mount Meru, near Arusha. There are several other mountains of that name in Kenya.

Other Masaai place-names describe the colour of local features: — a

Narok is the feminine form of Orok, black, which probably describes the colour of the river. Uaso Narok means the black river.

Aibor (white) also appears in Naibor-Murt which means the white neck.

Nanyuki means red-brown hence Engare Nanyuki red- brown water.

Sero means dun-coloured, hence Engare Sero the dun- coloured water.

Uas means dappled or striped, e.g., Oldonyo Uas the dappled mountain.

Pus or Wus means grey, hence Olpusu Moru the grey rock.

Nyiro means mud-coloured, hence Uaso Nyero the mud-coloured river.

Another group of places are called after rivers lakes, wells, etc.:—

Engare, water, has already been mentioned. Engari Motoni is the water of birds.

Uaso is a smallish river, c.f. Uaso Narok already mentioned.

Olgeju means a larger river and I have always imagined that Kajiado is a corruption of this, viz., Olgejuado —ado meaning long or deep, but I do not know if this is the official

explanation.

Laitokitok or Olaitokitok means a bubbling spring

Ngong means an eye and Ngong Nagare the water’s eye.

Ngong Mountain in Kenya is the place where the ancestor of the Oloiboni (the Masai medicine men) was found.

Naivasha or Naipasha means sea or big water.

Elwanata means an artificial water.

Olbal bal means a large rain pond.

Other places are called after natural features such as: —

Osoit means a rock, hence Soit Sambu the striped rock.

Olumoru also means a rock, hence Olpus Moru the grey rock already mentioned. In old maps Limuru, near Nairobi, is spelt Limoru.

Other places (especially mountains) are called after common objects and animals which they resemble, e.g.: —

Olmoti, a deep crater mountain in the Ngorongoro area, means a cooking pot.

Lolbeni, a mountain with two peaks, is called after the horned leather saddle bag so shaped to take the necks of the milk gourds for use on safari. (See illustration.)

Emunge, the name of a river in the Ngorongoro area, means the leg ornament of Colobus monkey worn by warriors—the connection seems a little obscure till you notice how closely the fall of

the white Colobus fur resembles the waterfall on the Munge river.

Esemingor, a mountain which flanks the road from Mtu wa Mbu, means a wild cat—because it looks like a crouching animal.

Olgos Orok, the local Masai name for the Loliondo border station in Tanganyika Territory, means black throat because the entrance to the station passes through a narrow belt of dark

forest.

Other places are called after climatic features such as: — Kijabe comes from Engijabe the cold wind which blows morning and evening.

Onainokanoka means a heavy mist.

Yet other places are called after the trees and shrubs which grow there: —

Loliondo or Olloliondo is the name for the Musharagi tree (Olea hochsetteri Baker) which- produces very heavy and durable timber, a favourite choice for box bodies and lorry

trucks.

Olmorigo, Olmorijio or Olmoricho is the tree whose branches and leaves are used to make arrow poison. Is Kericho connected with this?

Lorien and possibly Lorian comes from Olorien the wild olive tree whose wood makes the best firewood and the hot charcoal which the Masai use for scalding to the milk.

Arash comes from Olarash the Cape Chestnut with its beautiful mauve blossom.

Olgelai is a tree used for making bows and arrows.

(Toddalia is a botanical name.)

Lerai-Olerai is the yellow-trunked fever tree.

Olosogonoi is the Kassia tree from which the so-called Kenya steen heart timber comes.

Endulen is the plural of Ndulele the sodum apple, a ubiquitous shrub which produces round yellow fruits used by the natives for playing Bau.

Oldiani means a tree, also bamboo, which is sometimes pronounced Oltiani, the Kenya Londiani doubtless comes from this root.

Other well-known names are as follows: —

Longido the hill of whetstones; Engii is the Masaai name for whetstones which are abundantly found on the mountain slopes.

Rongai means narrow. It can also be used to mean “the narrow one,” i.e., the snake.

Lodwa is the Masai name for rinderpest which attacked the Masaai cattle at the end of the last century killing them in great numbers.

Kinankop comes from Kinokop the “burning country.” Kibaya is a Masaai name connected with Masai legend.

Arusha, I am told on good authority, comes from the adjective arus which means “possessed of good and bad spots”—usually applied to cattle but in this case applied to the mixed tribe of

people living round Arusha who ape the customs and dress of the Masaai.

Monduli, which is Monduli and not Mondul in Masai, is one of the place-names the meaning of which I am not certain. Most people think it is called after the big hole in the ground caused

by the red ochre mine nearby.

Others say it is connected with Olduli the wild castor oil plant which is indigenous. But as with all place-names there are many places whose names have no meaning because they are called

after some person or persons who lived there, e.g., Lolkisali, the mountain, was called after Olkisale the old man who used to live there.

Serengeti is another word about whose meaning there appears to be doubt. Olkerenget plural Ilkerengeti meaning barricades or forts seems the most likely explanation. Possibly these

referred to specially fortified encampments on the Serengeti Plains themselves. Or they may refer to the formidable looking semi-permanent stockades surrounding the mountain encampments to which the

Masaai, who graze their cattle round the Serengeti rain ponds, retire in the dry season.

This mountain area—on the lea of Ngorogoro crater is so devoid of natural timber that poles have to be imported from other areas to build semi-permanent stockades round the

encampments.

Ngorogoro. I have never heard a satisfactory explanation of this great crater. I have a suggestion but it is rather far- fetched. Aingor-aingoru means to look everywhere. If you stand on

the rim of the crater and look down you can see what is happening just about everywhere below; as though you were a God looking down from Mount Olympus.

But I must confess I have never heard this explanation from the Masaai. There is a place in South Masaailand called Njoronjoro—which is another suggestion, Njoro meaning well. But firstly

the Masaai pronounce Ngorongoro with a g sound not a j sound. And secondly although there may be wells in the crater.

It is one thing to make guesses about place-names in Tanganyika where I have lived; but it would be presumptuous to speak without authority on Masaai sounding place-names in Kenya with

which I am not acquainted. But I am interested in the subject and very much hope that one of the real experts from the other side of the border will supply some data on the subject.

The following well-known place-names are of Masaai origin: Longonot, Gilgil, Nakuru, which I am told means the waters of waterbuck, Elmentaita which means the plains of white flowers,

Marakwet—the grass brooms used by the Masaai which is a Masaai medicine—and Oltome which is the Masaai name for the rogue elephant.

The names Lesero and Isiolo have a Masaai ring. I have no authority for saying that Eldoret is a Masai word, it probably isn’t, but it sounds rather like Oldiret, the shield-like things

which the Masaai tie on the flanks of their donkeys when loading them for safari (see illustration). But it also sounds quite like Enderit which moans dust.

Which just goes to show how unprofitable it is to make guesses without local knowledge. If however I have irritated one of the real experts into putting pen to paper on this subject; then

I shall feel that this article is not entirely redundant.

In conclusion, I think, that those who are sufficiently interested in the subject to read this article will agree, that we do owe a debt to the Masaai for these descriptive and pleasant

sounding place-names; I for one hope that they shall not remain as a memorial to them, but rather that they may become a heritage, and that the Masaai who are intelligent Africans with character may

overcome the inertia which is at present keeping them in the background and come forward to play their part in the future development of East Africa.

I wish to acknowledge with many thanks help given by the Curator of the Coryndon Museum, Nairobi, regarding the meanings of some of the place-names in Kenya.

Narrated by Jane Fosbrooke

Nairobi’s First Thirty Years by Dorothy Myers

Nairobi: National capital and regional hub by R. A. Obudho

Nairobi ..A Jubilee History 1900-1950 by James Smart.

Dorothy Myers is a Chartered Town Planner who worked for nine years with Nairobi City Council.

Historical Photographs: East Africa Railways Corporation, United Nations University..

On the more recent volcanic outpourings from the Rift Valley twenty miles to the west has developed a region of well-defined ridges and valleys running roughly east-west, drained by the tributaries of the Athi River system. To the south and east is an area of more mature landscape, of gentler slopes and much lower rainfall. Not far south of Nairobi, the streams start to be seasonal only. Early travellers spoke of the deep rich red soil and forested slopes of the highlands, which contrasted with the drier treeless plains below.

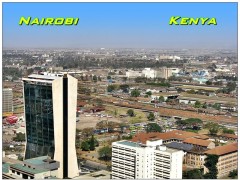

The site of what is now greater Nairobi straddles a physiographic, climatic and ethno-graphic area which has been of major significance throughout the growth and development of the city.

The general area was a boundary zone between pastoralists—the Masai—and sedentary sedentary cultivators—the Kikuyu. In the 1880s and '90s, the Kikuyu had been moving gradually southwards from Murang'a, and Masai control had been declining somewhat—possibly due to an outbreak of smallpox in the 1880s. Nevertheless the swampy watering places at the foot of the forest slopes, of which Nairobi was one, remained the territory of the Masai.

JUST OVER A CENTURY AGO, THERE was no town of Nairobi. Lion and rhino roamed freely where modern streets and buildings now provide a centre for the commerce and administration of Eastern Africa. A great city has arisen where once the explorers, the missionaries and administrators—“the grey company before the pioneers”— p itched their lonely camps, and along the route they marched now speed the shining cars of a new age.

Gedge, Jackson, Lugard. These were some of the men who passed through the Nairobi plain.

Ainsworth, Wilson. Tomkins, Martin, administrators and hunters.

Macdonald, Pringle, Austen, Twining, soldiers and surveyors.

Sclater and Smith, roadbuilders and engineers.

MacQueen, Andrew Dick and John Boyes, adventurers, traders and artisans.

Tucker, Poultney and Fisher, missionaries and teachers.

The plain on which Nairobi now stands was part of the “no-man’s-land” to high adventure; the unconsidered wilderness that stood between the Queen’s peace and Uganda, the country to which they carried the Flag and the Faith.

To them, Nairobi was unnamed, the swamp at the edge of the Kikuyu uplands, the last camp before the tiny outpost known as Fort Smith in Kikuyu which offered the first civilised comfort after weeks on safari. The wild plain inhabited only by herds of game and myriad birds, where the Nairobi River dispersed itself into a green swamp was a numbered camp, so many days march from the Coast. For the Reverend Fisher it was the “twenty-fifth march from the Coast.” Beyond, the forest concealed the savage Kikuyu, and the traveller risked painful death from poisoned arrows or spikes stuck into the undergrowth.

There were no inhabitants except the nomadic Masai who, from time to time, built their manyattas on the higher ground. They knew it as Nairobi “the place of the cold water” and sometimes their young warriors blooded their spears on lion at the edge of the swamp and achieved manhood.

In 1887 the trading and other activities which had been going on for a number of years throughout East Africa were formalised by the founding of the Imperial British East Africa Company. The trading capital of a large area to the east of the Rift Valley was at Machakos, administered from about 1889 by Colonel John Ainsworth. But the main sphere of trade was Uganda, the boundary of which was very much further east than at present.

It was for the protection of that route that various forts were set up along the way, including one established by Captain (later Lord) Lugard in 1890 at Dagoretti (a) on the fringes of Kikuyu country a few miles west of Nairobi. He chose the site especially for its location in between the Kikuyu and Masai areas, having in mind also its good water and fuel supply.

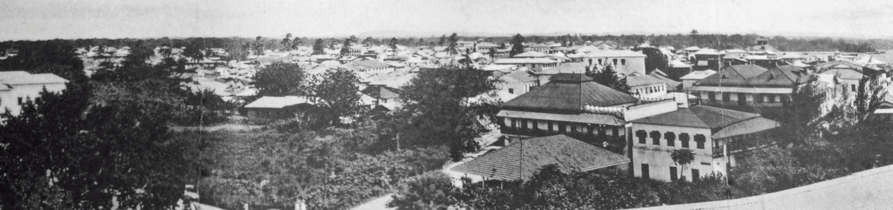

NAIROBI c. 1903. After the arrival of the Railway…Source: McVicar 1968.

Although a favourite Masai watering place, Nairobi itself had never been a popular campsite for the early caravans due to its dampness and mosquitoes. Rather

they had chosen to camp on the northern side of the river on the edges of the forest, probably somewhere around what is now Parklands.

Lugard's first camp did not last long. It was evacuated after a few months when the occupants feared a Kikuyu attack. The attack came and the station was

wiped out. A Major Smith returned two years later with greater strength to establish another station a little to the north. This one proved more enduring, since by this time, due to greater military

force and political manoeuvring, the British had managed to create a situation which was more favourable to their continued residence. The name of Fort Smith is still found in that part of greater

Nairobi.

In the meantime, north of the Nairobi swamp several villages had been j established. The Masai had recently been experiencing hard times due to famine and

disease and had become partly dependent on the Kikuyu for food; a Masai village was established in what is now Parklands. Later they moved further south again beyond the Mbagathi

River.

By the mid-'90s two more Masai villages had sprung up, one on the site of the present Muthaiga Club and the other towards the Mathare River. Some Somalis had

settled near the present Ngara Road and a few Kikuyu around what is now City Park on the fringes of the forest country. A market had started to the west near Dagoretti and another one near what is

now the junction of Ngara and Limuru Roads. Of the Dagoretti market, an early settler said:

The human traffic coming from Ngong was a wonderful sight, comprising mostly Masai women bringing their wares to exchange for all kinds of native food, beads,

ironware, Americani cloth, etc. Fort Smith in those days literally hummed with natives from all parts of the country. Of the other market, an old Kikuyu said: The market was started just after the

Europeans came. Kikuyus brought maize, posho, beans and potatoes to the market from one side and Masai came with goats and cows from the other A Colonel Sclater began the construction of a new road

to link the Dagoretti/Fort Smith area with the road from the coast. Parts of the alignment retaining the same name are still in existence well north of the city centre. It crossed the Nairobi River

at a point roughly at the present junction of Juja and Ring Roads.

On reaching Dagoretti, an open land which the Kikuyu, Kamba and Maasai used as a market area (great market = tha guriti in Kikuyu) he found it a good place to

build a station/fort where caravans proceeding inland, to Uganda could rest and get fresh supplies.

Waiyahki, son of Heinga was a peace-loving but brave Kikuyu chief who ruled in the Dagoretti (Ngongo Bagas) area of Kiambu about 10km west of Nairobi. In

October 1890, a British officer called Captain Frederick Lugard was travelling to Buganda on behalf of the IBEAC surveying a new route there as part of the British efforts to secure British

predominance there against perceived hostile German interests after the partition of East Africa.

https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GC5HZ0Q_fort-smith-waiyakis-world?guid=b8e76f8c-777b-4e8a-9062-303887900ad7

Nairobi: National capital and regional hub

R. A. Obudho

http://archive.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu26ue/uu26ue0o.htm

The foundations of Nairobi’s first local government was laid, pioneers that surpassed their own visions.

THE NAIROBI MUNICIPAL REGULATIONS WERE published on the 16th of April, 1900 under the powers vested in Sir Arthur Hardinge, H.M. Commissioner at Zanzibar by Article 45 of the East Africa Order-in-Council. The regulations defined the township of Nairobi “the area comprised within a radius of one-mile-and-a-half from the present office of H.M. Sub-Commissioner in Ukamba” and authorised the Sub-Commissioner to nominate annually a number of the leading residents or merchants to act with him as a committee.

In fifteen short clauses, the regulations laid dawn the rules for the conduct of the committee, prescribed the method by which a rate for lighting, policing and cleaning the town might be levied, together with the procedure of appeal against assessment. Moreover, the Commissioner was authorised to declare any area adjacent to the township a part of the township, and “thus extend the rateable area of the town.” Thus were the foundations of Nairobi’s local government laid.

The first meeting was held on the 24th of July, following, when five men, Messrs. Gilkison, Grierson, Huebner, Alidina Visram and Amir Singh sat down in the

Sub-Commissioner’s office to tackle the problems of the town: a madden of a bazaar, no street-lighting, unplanned shops going up daily, no proper streets, no conservancy, no refuse collection, no

police and no money.

Sir Arthur Hardinge

In 1887, he went to Istanbul, Turkey, under Sir William White, moving in 1890 to Bucharest, Romania. He accompanied the Russian Tsarevich on his trip to India 1890–91, and was then acting Consul-General in Cairo, Egypt, in 1891, under Sir Evelyn Baring.(Wiki)

GILKISON, Thomas Train

Profession: IBEA Co. Superintendent of Shipping and Customs in 1895, then Administrative and Judicial Officer to the Uganda Railway, Sub-Commissioner and

Vice Consul, Ukamba Province 1900, Magistrate and Asst. Judge, Nairobi..(Narrated by Europeans In East Africa)

GRIERSON, W. R.

Attended the first meeting of the Nairobi Municipal Council in July 1900. (Narrated by Europeans in East Africa)

HUEBNER, Richard Fritz Paul

Profession: Started safari business at coast taken over by Mr Schauer. In Railway coach with Ryall when he was killed but Huebner escaped and opened a general store at the turn of the century in Victoria St., Nairobi.. (Narrated by Europeans in East Africa)

https://www.africahunting.com/threads/paul-huebner-a-german-who-was-the-first-mayor-of-nairobi.38826/?fbclid=IwAR03ArWYN_ZnpeURQc7GgZT-jo0sSyPuXFQu4uzRTf4t1DyEUk7NY--msZI#:~:text=Paul%20Huebner%20%E2%80%93a%20German%20was%20the%20first%20%E2%80%9Emayer%E2%80%9C,was%20born%201869%20in%20Thorn%2C%20Westprussia%20%2FDeutsches%20Kaiserreich%2FGermany

Allidina Visram

born in 1851 at Kera, 22 km from Bhuj, sailed to Zanzibar at the age of 12, to serve as an assistant to businessman Sewa Haji (Paroo) in 1863.Quick to learn the tricks of the trade, he set up his own

caravans into the interiors, this further helped him establish his firm in several places from Dar-es-Salaam to Ujji to Congo. Functioning on a barter system of trade, he ex changed cloth, salt and

grains against local produce such as cloves, wax, and honey (ismailimail.blog).

Amir Singh

Sadly and unfortunately could not find anything on this gentleman who should be on parallel and alongside the others that are afore-mentioned to be all included in all Nairobi historic

books.

The first minutes of that first meeting are worth reproducing:

“It was pointed out by Mr. Gilkison that the first thing to be done was to have the Bazaar properly laid out and the value of buildings assessed to enable a rate of taxation to be fixed. The funds procured from this source to go towards forming a police force, a system of street lighting and conservancy purposes. Also to stop the extending of the Bazaar as being carried on at present, and that a proper map be obtained from the Uganda Railway showing the size and position of the plots. It was proposed by Mr. Huebner that at a certain date proper houses should be built, and any shopkeeper not complying with regulations would have his shop removed.”

Mr. Gilkison—a Protectorate official—proposed that the task of bearding the lion—the Uganda Railway —should be undertaken by Mr. Grierson, a Railway official and Mr. Amir Singh, and that if a plan was not forthcoming, to have a new plan made. By James Smart

History of Nairobi

Nairobi is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The city and its surrounding area also form the Nairobi County. The name “Nairobi” comes from the Maasai

phrase ‘Enkare Nyrobi’, which translates to “cool water”.

The area Nairobi currently occupies was essentially uninhabited swamp until a supply depot of the Uganda Railway was built by the British in 1899 linking

Mombasa to Uganda. The location of the camp was chosen due to its central position between Mombasa and Kampala.

Timeline Nairobi

1900s-1920s[edit]

- 1900 - Incorporated as the Township of Nairobi

- 1901

- Native Civil hospital opens.

- The Nairobi Club established

- 1904 - Norfolk Hotel opens.[2]

- 1905

- British East Africa Protectorate capital moves from Mombasa to Nairobi.

- Nairobi Parsee Zoroastrian Anjuman Religious and Charitable Funds established.[3]

- 1906

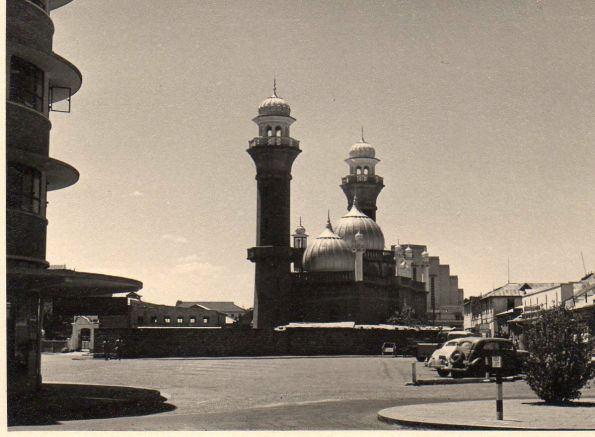

- Jamia Mosque construction started.

- Royal Nairobi Golf Club founded.

- 1907 - British Government House built.

- 1909 - East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society established.[3]

- 1910

- East African Standard newspaper headquartered in Nairobi.

- Museum of the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society established.[4][5]

- 1912 - Theatre Royal opens.[6]

- 1913 - Muthaiga Country Club founded.

- 1914 - Shri Vankaner Vidya Prasarak Mandal established.[3]

- 1917

- 1918 - Punjebhai Club formed.[3]

- 1919 - Nairobi Political Association formed.[3]

- 1920

Nairobi in the 1920s by Old Africa Mag

After the end of World War I Nairobi started to develop as a town. It had a population of 8,000 Europeans, 8,000 Asians and an indeterminate number of Africans. Lying at mile

327 of the Uganda Railway, it was at an altitude of 5,575 feet, standing at the front of the Highlands and on the edge of the great plains country that led down to the sea over 300 miles

away.

A Uganda Railways poster to popularize British East Africa

Formerly only the headquarters of the Uganda Railway, it had become the seat of the Governor and government offices. It had developed quickly from a mere collection of wood and iron

buildings to a town of considerable dimensions. The water supply came from a reservoir 13 miles northwest, and the electric power from a plant 12 miles northeast. There were three banks, two

English daily newspapers, a theatre and several churches, these being Anglican, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic. There was also a synagogue.

Cont........

https://oldafricamagazine.com/nairobi-in-the-1920s/

Barclays Moi Avenue branch oozes Georgian elegance six decades on

https://paukwa.or.ke/barclays-bank/

By...Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

What is in a name?

The Duruma Chief Mazera, gave his name to "the place of Mazera" or Mazeras where he once lived. In the earlier caravan days Mazeras was known as "Ganjoni" or "the place of ruins" owing to its being

frequently attacked by the Masai.

Mariakani is also of Duruma origin. The word, which means the "place of quivers", is derived from the native tradition that the Duruma and the Wakamba warriors met at this place in embattled array.

The Wakamba were defeated and, as they fled, they discarded their arrows covering the battle field with them.

"Maji-ya-Chumvi" was originally known as "Gulugulu" which among the Mijikenda was the name of a local stream. The name was later changed during the Swahili slave caravan era to its present version

which means "salt water".

"Samburu", between Mombasa and Voi was called "Kirauho" by the Mijikenda and the name "Samburu" was coined by slave caravans to denote

the last waterhole (except a small one which existed at Maungu) before Voi.

A story is told that the Swahili caravans were urged on to the Maungu and Voi waterholes by the Duruma herds shouting "Sambiburi", which may be taken to mean "Buzz along! buzz along!"

Mackinnon Road is, of course, named after Sir William Mackinnon, who played a leading role in the early development of the country.

"Maungu" means "a back" in Swahili. It is, however, thought possible that this word is a corruption of "Mayungi" which means water lilies found in the waterhole on a nearby hill. The proper name for

the station according to some historians should be "Marungu", the Taita name for the hill.

According to many Wataita Voi should be called "Ore" . The name Voi is a Ki-gunya/Bajuni word for gruel; the story being that the stream at Voi often dwindled to a mere trickle and, on this account,

only a small amount of gruel could be cooked by the Wa-Gunya/Bajuni slave raiders who normally hurried to Mbululu, the camp after Voi.

"N'di" is a Kikamba word for a "mortar" derived from the resemblance to a mortar of a rock close to the station.

"Tsavo" is a Kikamba word for "slaughter",. However, the word has no connection with the slaughter of numbers of Indian coolies in the days of construction of Uganda Railway. In fact, it relates to

the erstwhile devastations of the Masai.

"Mtito-Andei" is, of course, "Mtito-wa-Ndei" or "The Forest of Kites". The Masai are said to have constantly laid in-waiting in a nearby forest with intent to attack the Wakamba, following which many

were killed. The kites remained in the surrounding forests and fed on the corpses. After wards, the local river and station were both known as "Mtito Andei".

"Masongaleni" or more correctly "Mithongoleni" means the place of poisoned sticks. The word is derived from the poisoned sticks stuck by the Wakamba round their shambas to prevent bush buck from

eating their produce.

To the Wakamba "Kibwezi" was always known as "Kivwetse" which is said to have been derived from a former Scottish Mission in the vicinity. In the Mission garden was a volcanic rock which, after a

series of seismic movements, split and caused an underground stream to flow above ground near Kibwezi. Το the faithful ones, science is often cold and ungodly; but there can be little doubt that the

godly believed that the Mission padre struck the rock with his rod, in much the same way as did Moses of old thereby causing water to flow.

"Makindu", which is taken from the name of a nearby river was formerly known as "Kiumbi" (Kikamba for "the one by himself"). In Swahili, however, Makindu means "palm trees". Therefore, according to

some historians the place should more correctly be known as "Makinduni"- the place of palms.

Formerly, it is said, this stream was a dry river bed with a series of disconnected pools of water. thus resembling a man who is alone and silent "Kiumbi!" Seismic disturbances similar to those that

caused Kibwezi to flow overground started a permanent stream which caused the palms to grow.

"Sultan Hamud" is named after a Sultan of Zanzibar. Hamud bin Muhammad, to mark his visit to rail head at this point (Mile 248) in 1898. In the company of the Sultan was the notorious historical

figure and slave raider, Tippu Tib, whose name was derived from the sound made by his guns.

The full name for "Kiu" is "Kilima Kiu" which is Kikamba for "the black mountain". The old caravan road wound around the Kiu hills which were dark, sombre and forbidding, providing no light

patches.

"Konza's" original name was Machakos Road. From here a road went to the place of Masaku an early Wakamba Chief. The place of Masaku (Machakos)

"Em-Bagasi" or "Mbagathi" is the Masai name of the stream that crosses on the Nairobi-Ngong road and which flows through the Nairobi National Park to the east. It is interesting to note that the

Ngong Road was originally built out of the pro ceeds of a 15,000-rupee fine inflicted by the Masai paramount Chief Lenana on certain turbulent young warriors of his tribe the "elmoran".

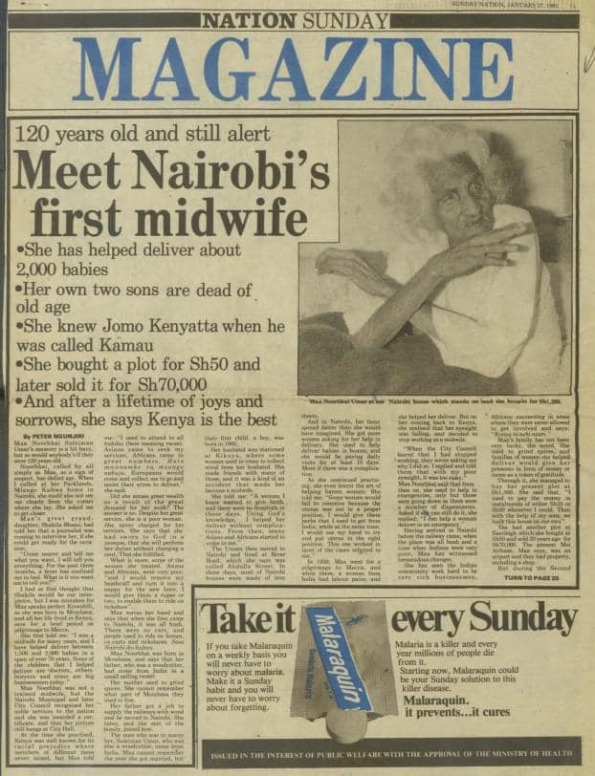

Meet Nairobi's First Midwife

Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un (: إِنَّا لِلَّٰهِ وَإِنَّا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعُونَ)…

Credit and thanks to … Rizwana Hetal

Our great grandmother.

Rumana Imtiaz Ladha Skauser Rashid

What a remarkable woman. So proud we are part of her. This is nation newspaper in 1979 when this article was written.

https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=3968548043207349&set=a.165274206868104

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dhadiama, I remember her from a very early, young age and this great lady was and is very close to my heart too, watching her matriarchy figure walk the corridors of the house in Haji Road,

Pangani, Nairobi

This lady had fantastic memory and was never ill from what I can recall in the time that I had known her, nobody ever argued with her, she was in control of all situations.

So many prominent figures looked up to her. I remember a bit about her family she had two sons (if memory serves me right).

Ahmed was one of her son, from her other son was Sidiq, Umar, Ramzan and daughter, Safia....

She was well known amongst all communities, no matter what religion or background one was from, she travelled far and wide to help many ethnic women and others with deliveries in her early

days and carried on for many years thereafter , in and around Nairobi.

Love to know more about her history, if any one can help……

Sunday Nation.... 21st January 1979

Saints of the Savannah Series: The Great Cleric

Buffalo and lions roamed the periphery of the swampy land that was uninhabited except for the meeting of the Kikuyu and Maasai peoples, who occasionally brought their cattle to graze. Wet, infertile and with a high-altitude, the Maasai called it Enkare Nyorobi – ‘the land of cool waters’. This area was never meant to be a settlement, but in 1896, the Lunatic Express arrived. The builders of the railway line set up a small depot and a camp on the plains. There was no plan beyond that; Nairobi was merely one link in a chain of such supply depots.

https://sacredfootsteps.com/2022/06/20/saints-of-the-savannah-the-great-cleric/

Nairobi: National capital and regional hub (East Africa Literature Bureau)

Click on photo to enlarge

Nairobi was Never Meant to be a City

http://owaahh.com/nairobi-was-never-meant-to-be-a-city/#more-2722

In 1899, the railway line construction from Mombasa to Lake Victoria found a good midway watering point that soon became a busy village called Nairobi (from the Maasai phrase Enkare Nyirobi, meaning “the place of cool waters” ). It quickly grew into a large town to become the capital city, despite no seaport or major river or mining industry around it.

http://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2016/09/24/nairobi-park-diary-the-concrete-jungle_c1422685

Names of major Nairobi landmarks in Colonial Kenya on the left, and their present day names:

1. From Duke Street to Ronald Ngala Street

2. From Victoria Steet to Tom Mboya Street

3. From Government Road to Moi Avenue

4. From College Road to Harry Thuku Road

5. From Bazaar Street to Biashara Street

6. From Salisbury Road to Princess Elizabeth Way, and then Uhuru Highway

7. From White House Road to Haile Selassie Avenue

8. From Coronation Avenue to Harambee Avenue

9. From Jan Smuts Avenue to Taifa Road

10. From 46 Victoria Street to Campos Ribeiro Avenue, and then Luthuli Avenue

11. From Sixth Avenue to Delamere Avenue, and then Kenyatta Avenue

12. From Hardinge Street to Kimathi Street

13. From Stewart Street to Muindi Mbingu Street

14. From Sadler Street to Koinange Street

15. From York Street to Kaunda Street

16. From Kirk Road to Nyerere Road

17. From Malik Street to Monrovia Street

18. From Gulzaar Street to Moktar Daddah Street

19. From Jeevanjee Street to Mfangano Street

20. From Ministry of Works Headquarters to Harambee House

21. From Connaught Road to Parliament Road

22. From Queensway to Mama Ngina Street

23. From Kingsway to University Way

24. From Sclater Road to Waiyaki Way

25. From Fort Hall Road to Muranga Road

26. From Doonholm Street to Jogoo Road

27. From Native Stadium to City Stadium

28. From Grogan Road to Kirinyaga Road

29. From Saldhana Road to Sheikh Karume Road

30. From Hussein Suleiman Road to Tubman Road

31. From Khan Road to Kumasi Road

32. From Reata Road to Accra Road

Information above courtesy of "The People" of November 27 - December 3, 1994;

Reasons Behind Naming of Nairobi Streets

https://www.kenyans.co.ke/news/40803-reasoning-behind-naming-nairobi-streets

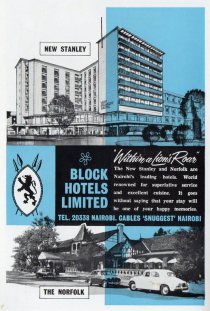

The Norfolk Hotel

Creating a tradition destined to endure was the Christmas present that Major C.G.R Ringer gave to Kenya and Nairobi (Nyorobi) The Maasai called it Enkare Nyorobi, the land of cool waters but the Kikuyu name for the land seems to have never made it to the history books. Some say without the Norfolk Hotel there would have been no Nairobi, it was here that all new comers with wealth arrived. Hotel was established in Dec 1904 on Christmas day, by Major Ringer the proprietor, hotel has 34 bedrooms and two cottages for married couple and much much more. Lions lurked in the papyrus swamp, the first men and women who landed in Nairobi considered the brackish swamp land perfect. The area was picturesque, with hills in the horizon and rivers crisscrossing the plains. The land was not suitable for farming, and certainly not for settlement, but it was perfect for grazing. For the Maasai and the Kikuyu, the plain was also a meeting ground, cutting between the highland farming community in Central Kenya and the nomadic community in the Rift. The letter further reminds Churchill of the 1902 recommendation to move the city “to some point on the hills.” Sadler told Churchill this was a critical point in Nairobi’s history; that his predecessor had said: “…when the rainy season commenced, the whole town is practically transformed into a swamp.” But the Board decided instead only to try to drain the swampy bazaar area. In 1898, a 25-year-old man called John Ainsworth had disembarked from a ship at the Port of Mombasa. He was an employee of the colonizing company called Imperial British East African Company, ambitious to make a career for himself in the new lands. Before that year ended, he travelled from Mombasa, up to the then capital city of Machakos, and into the tin shack town called Nyrobe. He built his house at Museum Hill to found the colonial administration, much to the chagrin of influential railway builders. Eager to make the swampy plains work, he planted Eucalyptus trees on the swamp to drain the water. Ainsworths legacy remains to date, with most of his efforts being the only reason why more and more parts of the swamp could be occupied.

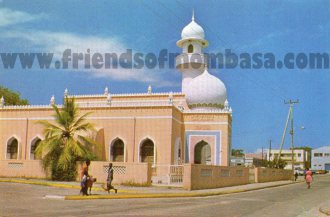

Jamia Mosque

Click below on history of Jamia Mosque

Khoja Mosque

Nairobi Town Jamatkhana: A journey through time

Nairobi’s Iconic ‘Town Jamatkhana’, Once the ‘Darkhana’ of Kenya, Celebrates 100 Years

https://simerg.com/2022/01/14/nairobis-iconic-town-jamatkhana-once-the-darkhana-of-kenya/

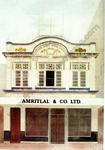

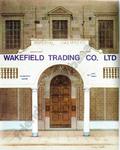

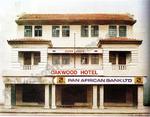

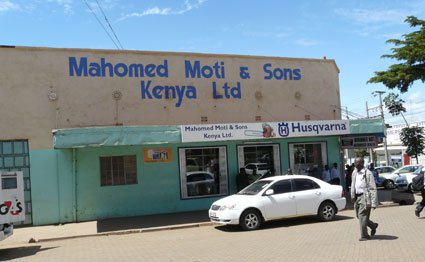

Indian business community of Nairobi in the earlier days and historic buildings...

If one really needs to establish what the Indian community were all about in terms of East African history it goes well beyond

East Africa, in fact history of the Indians is only concentrated in the East African Region seen as a core, for obvious reasons, due to major trading factors.

Indians and Arab history in that region dates back many centuries, the levy system was initially introduced by the Portuguese much later on, which was hated by the Arabs and Indians

alike.

Indians had a hand in everything along the East African Coast, Currency, Financial/banking system was operated by the Indians,

transport, Sea trading, Distribution, Wholesale, Retailing, Farming, Transport Inlands, etc. Indians and Arabs who built up century’s worth of historic trade in the region were systematically

targeted and stripped off as time went by.

The Indians were great traders in many aspects and business, in 1910 Sir John Kirk remarked on

the work of Indian Traders in Nairobi: In fact drive away the Indians and you may as well shut up the Protectorate. It is only by means of the Indian Trader that articles of European use can be

obtained at moderate prices.

Winston Churchill in “My African Journey”: It is by

Indian labour that the one vital railway on which everything else depends was constructed.

In most European’s minds the Indians simply did not matter. When writing of East African history in general, the role of Indians

is ignored or slighted. It is the British that get the credit for ‘pluck and determination’ building the Railways even when it is admitted that Indians suffered untold

horrors.

Most if not all prime geographical areas were also chosen for themselves and area controlled by the British Europeans for the

Europeans. The lack of information about Indians is due not only to the non-Indians’ disinterest (and often hostility). It is due also to the Indians’ own lack of Interest in writing about

themselves.

The question is, we had the British Colony enthrusted upon us at that time in India and were happy to oblige with the building of

East Africa in terms of labour, and so why is it that most of the Indian people who came over who had farming experience were never given any sort of land to farm in East Africa but the British

government opted for South African Caucasians to be brought over with a premise on allocation of prime free land as well as helping with finances and free labour?

Indians have always been fair traders, hardworking and can be passive at times in terms of carrying out dealings with the

Colonists, as we all know, in that era India was obviously under their rule.

The British feared that we had all the right ingredients to establish a new nation if we really wanted and thus made sure that they also took unreserved control of the situations in East

Africa.

If one really needs to establish what the Indian community were all about in terms of East African history it goes well beyond

East Africa, in fact history of the Indians is only concentrated in the East but is far afar and beyond.

Many people of the recent era may remember some of the household names or locations of the business or premises that they

operated from or still do to this day…

Here is a fantastatic hand painted old buildings compilation that has been revived by Katie Martin and Richard Martin through both their research for falling in love with archtectrial of that

era.

Richard Martin, an Executive magazine producer which he had been publishing for many years. This

was in fact a way to bring concern about the city to wider audience and in a sense, to “save” some of its historic buildings.

Shop in Biashara Street

This shop was built at a cost of about Kshs 45,000/- in 1931, by Lalji Visram and Co, to the design of K Varji Nanji, for the owners Karman Mepa and Co. They had come to Kenya in 1903, a family of masons that later turned to selling hardware etc., and they still have a shop at a different location in Biashara Street. Behind the shop on the right-hand side was a Hindu Temple dedicated to Radha-Krishna. It was a little corrugated iron structure that had been built by Lala Prasad (a Brahmin confectioner) in 1902. Unfortunately it was recently devastated by fire, though a small shrine remains. In the grounds of the temple Lala Prasad planted a little pipal tree — a sacred tree imported from India (Ficus Religiosa) — which can be seen, nearly 100 years old, in the background of the painting (on rear endpaper).

The hustler who helped build Nairobi, one block at a time

The tiny Baltic state of Lithuania is perhaps the last place one would expect to derive the success story of a Kenyan dynasty.

But it is from the wintry climes of this ancient land “spread like a counterpane across the cold plains of northern Europe” that Abraham’s People, a new book, begins an intriguing story that straddles a people’s persecution, an individual’s triumph and the taming of marshland that was to become Kenya’s capital city.

Cont....

Exploring Africa with Martin and Osa Johnson.

http://safaritalk.net/topic/1872-exploring-africa-with-martin-and-osa-johnson/page-4

When did Electricity Come to Nairobi?

WHEN DID ELECTRICITY COME TO NAIROBI

=============================

"November 1906 the company chose to use the first fall on the Ruiru River below the Fort Hall road, some 18-½ miles by road from Nairobi. A bungalow for the engineer was erected near the site of the

works and the task of damming the river was undertaken. The engineer James Ernest Bedding was appointed to be in charge of the Ruiru generating station. He lived there with his wife Elizabeth Hannah

Deakin and two daughters, Elsie and Eileen. But Elsie died at Ruiru aged eight, of inflammation of the brain. Bedding later joined the Thika Sisal Company.

The Ruiru dam, which was of concrete, was placed about 30 feet upstream of the fall, and was 200 feet long, 10 feet at the centre, on a base of 14 feet. It was difficult to get the supplies and

materials to the site on East Africa’s then-primitive roads. The dam had to be built before April, as a temporary dam and diversion of the river would not withstand the floods caused by the rains at

the end June. But the work was finished in good time."

http://oldafricamagazine.com/when-did-electricity-come-to-nairobi/

Click below for more info on EAPL

http://www.friendsofmombasa.com/british-empire-in-east-africa/e-a-p-l/

Fire Station on Victoria Street, Nairobi.

After the First World War, fire preventative measures were in the hands of the police until 1921, and the fire appliance were the property of the council.

After the War, in 1921 African Brigade was organised, during the 1921 and 1922 Fire brigade did not acquit itself as efficiently as it might,. It needed to be upgraded.

It consisted of a European fire master and deputy, twelve African firemen, a Fire Station with suitable quarters attached, a motor van equipped with two large 35 gallons extinguishers tanks hose,

hose cart, fire escape and hand extinguishers.

Nairobi and District

Progressive Nairobi

Nairobi and District printed by the East African Standard, Ltd 1940’s. The extract below was designed by Agnes Bompas and issued by the Municipal Council of Nairobi, Kenya

SOME years ago Sir Edward Grigg, then the Governor of Kenya, said that the standards of a community—its aspirations and its achievements—were indicated by its public buildings. Good buildings, he said, have an important influence on the outlook of the people. They mould the characteristics of citizenship; they mean the difference between pride and poverty of ambition. There are few things more arresting in Kenya than the modernity of Nairobi, the suggestion of purposeful confidence, and the strength of youthful vigour. At times it surprises the men and women who have seen Nairobi develop during the last twenty years; and it is deeply impressive to visitors who reach Nairobi for the first time from the great plains stretching eastwards to the Indian Ocean, or drop down from the African airways. The Capital of Kenya is the most remarkable town in Central Africa. It has no

Cover design by Agnes Bompas.

parallel among the Capitals of the world. Its growth has been almost as rapid and spectacular as the early strides of Johannesburg; its virility is exceeded, perhaps, only by Tel-Aviv in PALESTINE.

In the closing years of the last century there was no Nairobi worthy of a place on any map. Great game-infested plains spread out from the foothills of Ngong, from the lip of the Rift Valley. Raiding Masai warriors descended upon the Kikuyu, entrenched in their scattered villages behind a screen of forest. Lions sought their prey among the vast herds of zebra and antelopes; from the snow-crowned dome of Kilimanjaro to the glaciers of Mount Kenya savagery ruled over Africa. But the heralds of civilization had blown their trumpets. Winding up from the beaches of Mombasa the Uganda Railway was approaching step by step through Nature’s Zoo, invading the home of the wild things, and with it, when it reached the gateway to the wind-swept highlands, came the pioneers who made history, building in the wilderness a worthy centre for their race.

Racing at Langa Langa October 8th 1951

Another batch of images from the 'Happy Valley Album' of racing at the Langa Langa circuit in Nakuru, Kenya. The images were all labelled in their album and I have reproduced these comments next to each picture.

http://reddevilmotors.blogspot.com/2019/07/racing-at-langa-langa-october-8th-1951.html

12 Stunning High Quality Photos of Kenyan History

https://owaahh.com/12-stunning-high-quality-photos-of-kenya/

Nairobi Dam

The black bass flag flies straight out in the strong northwest monsoon wind. A dozen sets of pale-blue sails whip and crackle, and a dozen Enterprise racing

dinghies tug t their painters at the home-made oil-drum and plank jetty. Mixed among the impatient boats are half a dozen meet-lined Fireflies, their sails fluttering like butterfly wings; and some

of the little Herons and a few handicap oats are either moored or already out on the water.

The club with the sign of the black bass is 314 miles 5v road) from the sea and under five miles from the centre t Nairobi city, on the road to Langata. It is

a sailing club— the Aquasports Club of Nairobi—5,500 feet above sea- level, where those who love messing about in boats meet every week-end of the year, even through the month’s laying-up, to sail

and tinker, to race, to paint, varnish and pair, and at the end of the day to gather in the snug club-house they built themselves for something to soothe parched throats.

My sailing before I came to East Africa had been done in at magnificent stretch of water in Chichester Harbour, here the sou’wester can whip up a tidy sea and

wind that ill capsize the stoutest dinghies and break the strongest ar. It is a haven studded with little islands where the i-birds call sadly and raucously, and with sandy beaches lich are paradise

out of season and almost impossible to t on to in high summer. You can sail for miles on the lie tack and run or reach for half an hour on end.

In a modern dinghy the planning (when the bows of the boat; out of the water, the water astern flattens out, and there is a true sensation of speed) has to be experienced to be believed. There are at

least eight sailing clubs in Chichester Harbour, with class meetings and regattas on every week-end of summer and the sound of the starting cannon is always somewhere to be

heard.

From this paradise for dinghy sailors I came, as others had done before, to Nairobi, and reckoned that except for coast holidays, my sailing was over for a few

years. That is until I happened to knock up, one Christmas, a little cockleshell of a dinghy for my seaside holidays and, returning from them, thought it might be fun to see how it sailed on the

Nairobi Dam. And that was my introduction to some of the keenest, most exciting sailing I have ever had.

They accepted my little boat tolerantly, though it sometimes got in their way and was nothing to look at. They knew, I’m sure, though they never said so, that

before long I would get on to proper boats. I did, by-way of a touchy little double-chine job with fifty square feet of sail I built myself and raced, for at that time the Dam had half a dozen of

this particular handicap class. Then I graduated to Fireflies, my present and I think lasting love, which my son and I have raced this past two years, and which has given us so much fun and

thrills.

When you see the Dam, you are apt to wrinkle your nose the first time. It is muddy-looking, it is small, it is almost bare of trees and the sparse grass fights

the rock that shows through the scarce soil. It is nothing to look at. Yet towards the end of the day when the white egrets are flapping their way home to the ten-foot-high reeds on the other side

from the club-house, when the wind has dropped and the frogs start croaking, when the sun goes down over the Ngong Hills, then Nairobi Dam has a great deal about it.

Those of us who sail on this mile-long, pear-shaped area of water (it belongs to Nairobi City Council), whose 425 million gallons of water can be like glass in

the sluggish, between-monsoon periods, or whipped into small waves and even white horses at peak-monsoon times, take some risks for our sport. They say there is bilharzia to be caught in the Dam, and

sometimes when you capsize or are paddling about at the water’s edge to launch your boat from the shore you cannot help thinking about those nasty little wriggling worms that can pierce your skin and

give you the disease. Yet I believe no one at the club has caught bilharzia so far!

We have chaps in the club who are among the best sailors in Africa. One of them is an airline pilot who, so it is said, keeps up his sailing with shares in

boats at Aden and Bombay where he sometimes calls. We have veterinary surgeons, electrical engineers, civil servants of all kinds, accountants, printers, doctors (one well-known practitioner lost his

trousers during a capsize, unique among Aquasports folk), school-

masters, policemen, prison officers, soldiers, airmen, all sorts of people with all sorts of skills. They are matched by their womenfolk, many of them hardy types in spite of not looking the least

bit tough, who regularly sail with their husbands or boy-friends, are cursed at, often soaked, always wind-blown and sunburnt, sometimes clinging to their upturned boats; but they sail the boats

themselves at our twice-a-month ladies’ races and do so with distinction.

You can hide nothing on the water. The merest whisper, unless there is a gale blowing, can be heard by people in boats yards away. “Get that . . . jib-sheet

in!” is a common enough, if un-gentleman like, injunction to many a woman- crew during races, but no one turns a hair. And the races are run according to a most complicated (and common- sense) set of

rules, laid down by the Royal Yachting Association, so that everyone has an equal chance. Mind you, some are better “sea-lawyers” than others, but remembering there are five seriously contested races

every week-end, it isn’t all that often a white handkerchief is seen fluttering from the stays of a protesting dinghy. Perhaps this is because the protest meetings after racing take up a lot of time

which could be better spent chatting or drinking in the club bar.

Nearly 200 people and fifty boats provide the sport at the club. It is fair to mention that there is also a motor-boat and hydroplane section, as well as one

for anglers and another for water-skiers, although we sailing folk naturally believe it is sailing that matters. Every so often other clubs from up-country or the coast visit the Dam and sail against

the Aquasports folk. Then the officer-of-the-day, in his special vantage point fifteen feet above the club-house, has plenty to do, while youngsters help him hoist the right flags for starting and

ring the bell for the ten- and five-minute warnings, and the starts. Then there is much jostling as the boats try to pick the best position to cross the starting line and there are loud shouts of

“Starboard!” as the better- placed ones shout for right of way. You miss the sea-tang, of course, and the liveliness of the tides and currents, the cold winds and the summer sun of Britain.

But there are compensations, for in our climate you need never wear anything except shorts and “tackies”, unless you are fussy. If you do go in, then the water is warm and you are sure to be within

easy reach of the rescue boat. There is no close season except the one month the club sets aside to give boats and men a respite, for nowhere else can there be eleven months a year of racing,

punishing to everyone even though there is so much opportunity to gain experience.

You miss the long evenings of the English summer, too, when you might be sailing back up the Emsworth Channel on the flood with the sun setting to port of you and the gulls and peewits calling. Still, why grumble? The giant Goliath herons, the darters, the little wag-tails, the king-fishers, the odd flamingo and ibis, the lily-trotters and the terns of the Dam have their value, too, along with the Hindus chanting at festival time by the Dam’s edge, or the distant rhythm of drums from an African ngoma coming across the murkv Dam in the evening time, as the tropical sun sets and the club-house lights shine out gaily.

Nairobi in the 1950s

Click below on photo

Click below for interesting personal collection of the 50's

Beautiful Scenery of Parklands Area in Nairobi Kenya: Westlands, Ngara, City Park & Diamond Plaza

Mikhail Kuzi Historic Kenyan Video

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLR0dYxzAXFDOmeXiCqMvvTWKno0caAHUr

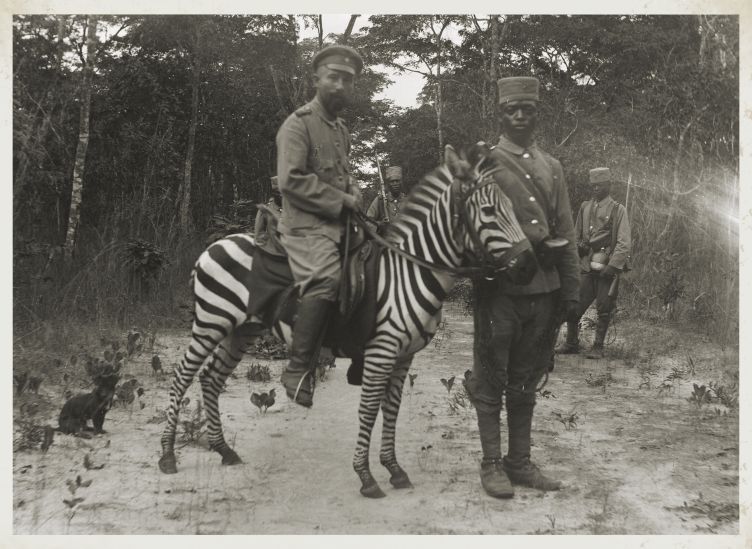

DRAUGHT AND RIDING ZEBRAS

Because of their resemblance to the familiar horse, there has always been great interest in taming and training zebras as riding and harness animals. In the 1760s, French naturalist Buffon belived that zebras could replace horses and there were rumours in Paris that the Dutch had already trained a team of zebras to pull a cart. Eccentric aristocrats around the world had zebr-carts at various times in the 19th Century. These photos are from the late 19th century and early 20th century.

East Africa Cities and Towns

Cities and Towns

To see the full version, click on the thumbnail of the images. Photo enlarges to fit your display. Some photos may enlarge even further using icon at lower right corner of the image. To return to this page, click the Back Arrow.

This page includes images and photographs with a connection to this site. To add your photo, please contact KenyaKorner & put Kenya Photos as the subject.

http://www.world-guides.com/africa/east-africa/kenya/kenya_districts.html

Hilarious Origin of Names of Towns and Locations in Kenya, Click below

Why was Ukambani town named after a Sultan?

http://mobile.nation.co.ke/lifestyle/Sultan-Hamud-Town/-/1950774/2020842/-/format/xhtml/-/7bdfa/-/index.ht

Stories behind Nairobi’s street names

KENYA HISTORY TODAY

ESCPADES OF JOHN KAMAU - A KENYAN JOURNALIST

http://johnkamau.blogspot.co.uk/2015/05/nairobi-was-built-on-wrong-place.html

https://www.facebook.com/historyworks

An art of digital emotions from me to you.

Click on Photo

Interesting photos of around modern Nairobi, Kenya:

http://www.nairaland.com/51356/nairobi-photos-kenya-beautiful-east

Nairobi

Nairobi /naɪˈroʊbi/ is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The city and its surrounding area also form Nairobi County. The placename "Nairobi" comes from the Maasai phrase Enkare Nairobi, which translates to "cool water".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nairobi

A Walk Through Pangani and Ngara

Nairobi Colonial Film

Travelogue of everyday life in Nairobi, Kenya, concluding with the ceremony granting the town the status of a city.

Meru's oldest business that is still thriving, 100 years on

Various Kenyan Cities and Towns

http://nipate.com/cities-of-kenya-50-t36391.html

Eldoret

http://oldafricamagazine.com/early-white-settlers-from-britain-in-trans-nzoia/

Kitale

The Kisumu Town Clock was built in memory of Kassim Lakha who arrived in East Africa in 1871 and died in Kampala in 1910. It was erected by his sons Mohamed, Alibhai, Hassan and Rahimtulla Kassim.

http://kisumucitycouncil.wordpress.com/2012/10/29/kisumus-landmarksthe-town-

Kisumu in Photos

Kenya Wildlife Services

http://www.kws.org/parks/parks_reserves/KIIS.html

KISUMU DALA EVENTS

http://kisumudalaevents.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/the-shocking-truth-about-kisumu.html

Click on Photo for more on Kisumu

BACKGROUND OF KISUMU CITY

https://kisumucitycouncil.wordpress.com/2012/10/25/background-of-kisumu-city/

Interesting/Nakuru.

A LOOK AT KENYA THROUGH THE YEARS – PictureBlog 1914 – 1990s

Industry East Africa-USHA, Sewing machines and fans, SERVE THE WORLD..1962-3

The name USHA requires no introduction to this country. When one thinks about a sewing machine or a fan one no doubt remembers USHA. As pioneers in the field of light Engineering Industry, Jay Engineering Works, the manufactures of Usha Sewing Machines and Electric Fans, hold a unique position in India.

Twenty-five years is not a very long period in the life of an industry, but for Jay Engineering Works this period has been one of great developments, the magnitude of which has exceeded all forecasts. It was in a small garage in February 1935, that the first USHA sewing machine was made with the help of only four workers and today we have an establishment consisting of more than five thousand workers.

In 1938 when the firm was registered as a public limited company a significant development took place which meant a turning point in the fortunes of the company. The eminent industrialist, the late Sir Shri Ram, Kt., our Chairman, saw the great future ahead of us as manufacturers of sewing machines and extended his patronage.

During the Second World War the factory was requisitioned by the Government for the manufacture of automobile and aircraft components.

When the war came to a close, manufacture of sewing machines was resumed. Plans for expansion were taken in hand and new machinery from the U. K. and U. S. A. was imported and installed. We are now manufacturing all the components for sewing machines including needles, the manufacture of which was taken up in 1957. Present production of sewing machines is 25,000 per month. Another sewing machine manufacturing unit with a similar capacity of 25,000 sewing machines per month has been stated at Hyderabad (A. P.) where we are manufacturing mainly our new model the Ushamatic Zigzag machine which has recently been introduced in the home market. Streamlined sewing machines which hitherto had been exported to foreign markets only have also been introduced in the home markets as well.

In 1957 a modern factory was set up and the manufacture of electric fans was transferred from the old factory to the new one. We are proud to say that our new factory is the largest single unit fan factory in the world which is turning out over 50,000 fans per month at present and the output is expected to go up to 75,000 per month very shortly.

A separate plant for the manufacture of Electrical Stampings has been set up in our fan factory. This has enabled us not only to meet our requirements but to supply to other manufacturers as well. Regular production of Exhaust and Fractional Horse Power Motors has already been started and introduced on the market.

We are now exporting our products to more than 50 countries in the world including the highly industrialised countries such as the U. K., U. S. A, Canada, etc. Our export in 1961/62 was nearly Rs. 1.00 crore. Several new contracts have been established during the last year and we expect to build up regular business with them in the months to come. Last year we also exported our sewing machines to West Germany for the first time.

A glance at our figures of production and exports will show the progress we have made in such a short time against heavy odds. This is the result of mass production methods made possible by the application of research, training of personnel, installation of up- to-date machinery, standardization of the products, and mechanisation of various processes involved in the work of production. This has resulted in lower cost and lower price to the consumers.

The increasing demand for our sewing machines and fans is a positive proof of the growing appreciation of our products based in their quality and low price.

Now we are exporting our technical know-how as well. We have set up sewing machine assembly plants in Colombo (Ceylon) and Saigon (S. Vietnam) and have sent a group of our engineers and technicians there. Assembly of our sewing machines has already started in these countries. We also hope to start such units in Burma, Thailand and Iraq in the near future.

We have a proud record for pioneering work in the Light Engineering field. With these expansion plans we look into the future with ever-increasing confidence Usha’s products are represented in East Africa by Usha Sales Private Ltd, whose office is situated in Jeevanjee St., Nairobi.

JACKO AFRICA SAFARIS

Click on Photo

Welcome to JACKO AFRICA SAFARIS - your gateway to the world of classic travel in the most wild and un-touched parts of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Seychelles, and Southern Africa. A safari in this region can take you over open savannah plains whilst passing snow-capped mountains, or through dense tropical forests and end up on a deserted island beach.

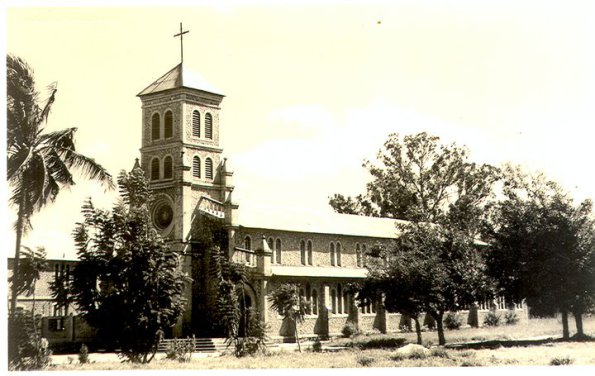

Tiny chapel that keeps art, History alive through ages

Church built by Italian prisoners of war interned in Kenya during second world war.

By: Karam Bharji

https://karamvisuals.wordpress.com/2009/01/26/church-built-by-italian-prisoners-of-world-war-2-in-kenya/

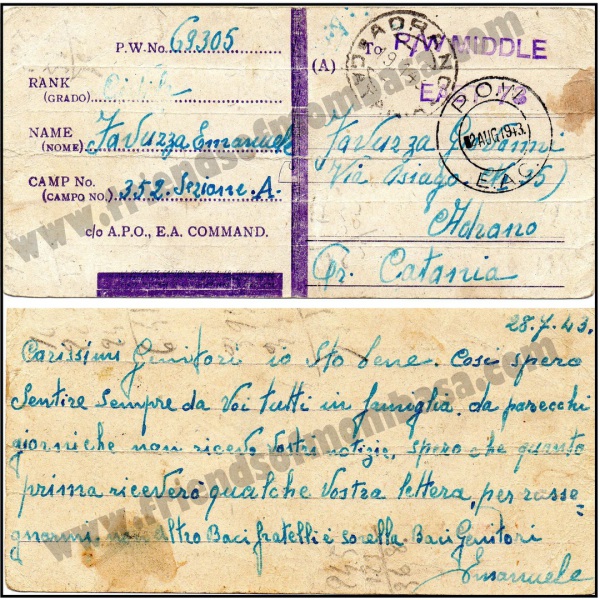

For more than five years, between 1941 and 1947, when 21,500 British citizens lived in Kenya, they were vastly out-numbered by the 55,000 Italian prisoners of war, spread over eleven prisoner of war camps.

Of these, only one, Camp No. 360 at Ndarugu, that held some 10,000 prisoners, has miraculously escaped sub-division and new constructions. It was “discovered” by Mr. Manos in 2007, with the church and the monument built by the prisoners almost intact. In 2011 they were gazetted by the Government as “monuments of the history of Kenya”.

http://www.kenyabuzz.com/whats-on/conferencetalk-ndarugu-camp-360-and-the-italian-po

Invasion of Italian East Africa

19 Jan

1941 - 16 May 1941

In East Africa, the earlier picture of conquering Italian troops was no longer seen in early 1941. Although the Italian Viceroy Duke Aosta had taken Sudan, Kenya, and British Somaliland early, by

this time the Italian troops were demoralized from their countrymen's losses in North Africa.

http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=108

Italian Prisoner of War Mail from East Africa

http://www.thingspostal.org.uk/eastafrica/postalhistory.html

St. Theresa's Cathedral Tabora, Tanzania built by the Italians prisoners of war in 1940-45