|

SPECIAL

REPORT |

|

MOMBASA ACHILLES ATHLETICS |

http://www.goanvoice.org.uk/newsletter/2003/Feb/issue1/supp1/Seraphino.html

https://issuu.com/skipfernandes/docs/stars_next_door_book/s/11653624

Pioneer in Kenya's athletics Seraphino Antao, a champion

Pioneer in Kenya's athletics Seraphino Antao, a champion

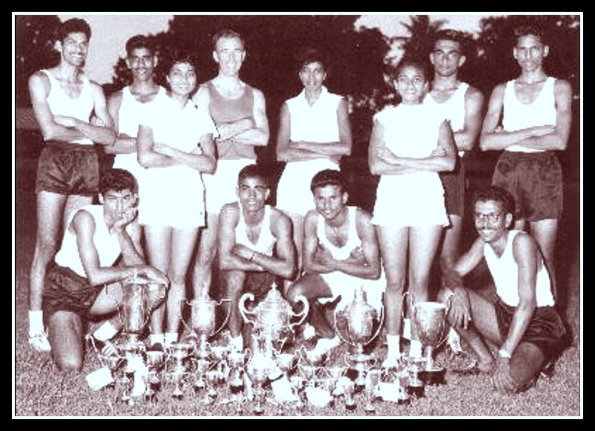

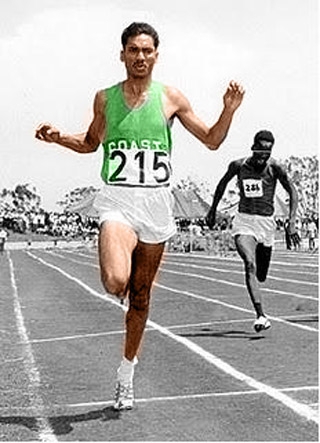

Seraphino Antao is the most accomplished sprinter Kenya has ever produced. He won the gold medal in the 100 yards and the 220 Yards at the 1962 Commonwealth games. In the process he became the first Kenyan ever to win a gold medal at a global event.

http://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/magazine/-/434746/467816/-/item/0/-/11q2mew/-/index.html

http://kenyapage.net/commentary/players/seraphino-antao-kenyas-greatest-sprinter/

Seraphino Antao

Athletics Kenya

Athletics Kenya (AK) is the governing body for the sport of athletics (track and field) in Kenya. It is a member of the IAAF and Confederation of African Athletics. AK organises athletics competitions held in Kenya. It also sends Kenyan teams to international championships. Isaiah Kiplagat is the current chairman of Athletics Kenya. AK is headquartered in Riadha House, next to Nyayo National Stadium, Nairobi.

Cont:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athletics_Kenya

Famous Athletes from Kenya

List of the most popular, renowned or famous athletes from Kenya. List includes the most notable athletes from Kenya, along with photos

when available. This list of Kenya athletes is alphabetical, but can be sorted by any column and answers the question "what famous athletes are from Kenya?".

Read more at http://www.ranker.com/list/famous-athletes-from-kenya/reference#2rUG7DkOwwzV3RzA.99

http://www.ranker.com/list/famous-athletes-from-kenya/reference

More:

http://kenyapage.net/athletics/overview.html

http://allafrica.com/athletics/

My Personal Story

I was fortunate to meet up personally with the great man Kipchoge Keino, Henry Rono and many others who lived in or around Eldoret, Kapsabet and Nandi Hills, etc.

I first met Kipchoge Keino in 1980, he had a Sports Shop on the main street opposite the only cinema in Eldoret and was thrilled to have chatted to a mild mannered person and a decent being at that. After our initial meeting I met up with him on several other occasions.

My Uncle and Aunt have lived in Eldoret for many many years and there was a tale which always stuck in my mind” My Aunty loved gardening vegetables and as usual she was working away in her vegetation portion of the allotment and whilst working away one day she came across this man and greeted and started speaking to him from a distance, who was working away minding his own business in the adjacent plot of land to the back of my aunt’s house.

My Aunt called him over and after a brief conversation she asked this man proudly “do you know the owner of the plot and house you are working on, belongs to a famous man called Kipchoge Keino” and she started telling him how famous and wonderful this man was for Kenya and got carried away and with it, it virtually become an oration, this poor man stood there with respect listening to her going on for a few minutes and tried to intervene a few times, but those who know my my aunt, she is the type who just carries on and never stops once starts jabbering away.

After several minutes of her giving him an ear ache this man gathered up enough courage and told my aunt “Mama mimi nee Kipchoge Keino minywe”, (I am the very Kipchoge Keino you are talking about)

My aunt did not know where to put herself and that has always been an anecdote within the family for many years now.

Welcome to the 62nd Safari Rally

http://www.safarirally.org/2-about-the-safari/16-foreigners-to-battle-locals.html

Mohamed Ahsan the legendary Speedway Motor Cycle Rider

Mohamed Ahsan with the largest and most coveted trophy he ever won during his racing career. He is wearing his famous helmet displaying his competition No.80. All the trophies won by Mohamed Ahsan and kept by his son and daughters as cherished memories of their late father.

Muzzafar Khan signs a copy of his memoirs "FROM THE LAND OF PASHTUNS TO THE LAND OF MAA" to Javed Ahsan the only son of the late Mohamed Ahsan the legendary Speedway motor cycle rider in Kenya in the 1950s.Looking on is Parvez Iqbal.

A Tribute to the Legendary Speedway Motorcycle Trials Rider: The Late Mohamed Ahsan.

OUTSIDE RALLYING circles, few of the big internationals are well known, but one of the exceptions to this rule is the East African Safari, which can stir thoughts of rugged, long distance motoring in places as disparate as Australia and Alaska, or Zanzibar and Zagreb. This worldwide acceptance as a tough motoring trial is due to the most obvious reasons. Despite the fact that it is a very modern rally, dating from 1953, its speciality is in providing roads and weather conditions that bring even the modern motor-car to its knees and often deny it the right of passage. Situations where cars are stuck in mud for hours, or where the cars of finishers are literally held together with string, are far from rare. Add to that all the possibilities of meeting wild animals, having the car pushed by natives and building your own bridges to cross a swollen stream and you can realize why the Safari has its reputation.

The early Monte Carlo Rallies from 1911 up to the beginning of the World War 2 possessed this air of improvisation and of battling against the elements. In pre-war Montes, reaching Monaco was the ambition of every driver, and once there, penalties could be found by means of a test or concours to decide the winner. Stories of snowdrifts and shovels were rated higher than trophies, while several competitors became legends without even finishing a rally. Since then, with better tyres, better roads and the advent of the snowplough, the Monte has developed into a test of speed in wintry conditions. Something was needed to replace it as a source of motoring tales and the Safari grew to fit the bill.

It always seems to be the British who devise the most rowdy and complicated sports: rugger and cricket are by no means the only examples. They were also the instigators of the East African Safari, though right from its earliest days it has reflected the cosmopolitan life of East Africa itself. The rally started life as a fun-for-all run round the three countries - Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania - that comprise what is known as East Africa. It had rules, but not too many, and though there was quite a lot of commercial interest, there was an essentially amateur spirit. It caught the interest of local people at once, and it is likely that even had it not found wider acceptance with overseas drivers and entrants it would have survived in some slightly more modest form purely for the satisfaction of the locals. In any case, it turned out to be the major sporting event of an area that was seeking a corporate identity, and has never had its popularity challenged by anything so mundane as football or horse racing.

From 1953 until 1959 the rally could be classified as a local event. Certainly it gained an international permit in 1957, after Maurice Gatsonides had competed in 1956, and in 1958 and 1959 it had a sprinkling of overseas drivers. But i960 was the year it changed its name from Coronation Safari to East African Safari and brought the start of professionalism. Firstly, in recognition of the fact that the organization of the rally was a job that had grown too big for a part-timer, the Automobile Association of East Africa appointed a full-time organizer, Cyril Hutchence. Then for many years the rules had been getting more complicated and these were revised especially in respect of those matters that had led to the protests of 1957 and 1958. The start order was decided just by ballot, not by considerations of class, while the classes conformed for the first time to the international capacity divisions and not to the original classes based on the Nairobi price of the car.

For these and other reasons, the sixties were the golden days of the East African Safari. The routes were made progressively tougher, and the time schedules shorter in order to combat the increasing facility with which modern cars traversed even the bush roads of Africa. These ten years produced nearly all the changes which have gone to make the modern Safari Rally. Until 1967, the only cars allowed to run were production models in standard trim except for things like underbody protection and extra tankage for petrol. On one occasion, when a doubting official did not believe that a certain car possessed a laminated windscreen as standard equipment, he was taken to the dealer’s showroom where a windscreen in a similar car was shattered for his enlightenment. However, 1966 was the last year of the standard production car, and since then the first four Groups of the Federation Internationale de VAutomobile Appendix J - standard and tuned'Touring cars and sports cars - have been allowed to run.

The dramas of the sixties can be recalled by the two extremely wet years when both times only seven cars were classified as finishers, and then only after large extensions to the maximum lateness time. Or by John Manussis winning with two co-drivers in a big Mercedes. Or by Tommy Fjastad winning in a little Volkswagen. Or by Peter Hughes defeating Erik Carlsson by ten minutes to give Ford valuable publicity for their first Cortina. Or by Bert Shankland’s two successive wins for Peugeot. Whenever there was a Safari there was something newsworthy, whether it was cars hitting wild game, or natives throwing stones through windscreens. But the best story, which ran the entire decade, was how an overseas driver had never won the rally outright.

Erik Carlsson had finished second, both Pat Moss and Anne Hall had been third, John Sprinzel had come fourth and Lucien Bianchi fifth, but an overseas driver never quite pulled it off - and it was not for lack of talent. At one time or another, most of the best British drivers such as Ronnie Adams, Edward Harrison, Vic Elford, Paddy Hopkirk, Peter Harper and Henry Taylor ventured down to drive the Safari, not to mention other top Europeans like Rauno Aaltonen, Eugen Bohringer, Tom Trana, Carl-Magnus Skogh and Gunnar Andersson. What defeated them seemed to be a lack of experience in handling the conditions, plus an inability to pace the car in order to make the suspension last the distance. As many of them returned year after year, so the legend grew that no one would ever beat a local driver, a legend which was to persist until 1972 when, as we know, the 20th East African Safari saw European drivers take the first two places overall in a rally which had reverted to a more traditional type of route.

The East African Safari has evolved a great deal since its inception, and any understanding of the modern event and the way it is regarded can only come from a study of its history. And its history is both the story of the changes which have taken place in the structure of the event, and of the men that have competed in it. So let us go back to the beginning. . ..

In 1936 a man called Barry Englebrecht won the Nairobi-to- Johannesburg cross-country race. The fact that he drove in many of the early Coronation Safaris was no coincidence for it was out of this spirit of showing that the countries of Africa could be visited by road that the first Safari was born. One of the earlier post-war motoring events in Africa was the Nairobi-Cape Town- Nairobi run for which the brothers, Neil and Donald Vincent, from Kenya, set a new record in 1950. Their cousin was a Nairobi businessman called Eric Cecil, who was passionately interested in motorsport, and it was out of post-prandial discussions by these three that an idea emerged for a long-distance event round East Africa.

An ideal opportunity for holding such an event was provided by the national holiday given for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, all the people involved being amateurs who could only give their time to run the rally out of working hours. This tradition has persisted until today, and since 1957 the rally has been run during the Easter holiday when officials can be sure of four clear days. However, the rally’s original name, the Coronation Safari, was retained until i960.

The first plan was to run a clockwise circuit of some 1,500 miles round Lake Victoria, but poor ferry connections caused the idea to be scrapped. It is interesting to reflect that these same ferries so far have prevented the running of a ‘Round the Lake’ Safari, though the AA have plans for one in the future and have already plotted the route. Instead, the first Coronation Safari was run as a here-to-there-and-back event as there were not sufficient all- weather roads to make a conventional rally route. It was intended to have just one starting-point, but as this would have meant Tanzanian entrants driving their cars over a large part of the rally route to Nairobi before the event even began, they decided instead to nominate three starting-points, one in each country, at Nairobi, Kampala and Morogoro. The routes varied slightly in length but they used as much common ground as possible before finishing at Nairobi. There were six passage controls and times were taken at the starts and at the finish. There was no route definition other than by place names, and much was left to the sporting nature of the competitors.

The entry was restricted to standard production touring cars (Group 1 of Appendix J) without any modifications, and pre-rally ‘preparation’ involved no more than sorting-out the de-ditching gear and giving the car a general service. It has always been the practice of Safari drivers to use cars which have already covered many miles so that they know them well and have discovered any weak points. In the beginning, this was by force of necessity but it grew into a method of obtaining a Group 1 car that was sorted-out yet stayed within the regulations. There are stories of drivers purposely having pre-rally accidents with their car in order to be able to strengthen it while repairing, but these come from a later era.

The cars were organized into classes based on the Nairobi retail price, which gave a car that was good value for money a chance to prove it. Different average times were set for each class, ranging from 43 mph for Class A to 52 mph for Class D, and most surprisingly they were not started at intervals but en masse. At Nairobi, where forty-two of the fifty-seven entries started, the Mayor led the convoy to the end of the 30 mph limit and then, like the pace car at Indianapolis, just pulled aside and the ‘race’ was on. It was a little unfortunate that there was this connotation of racing in the first event as the organizers spent years living it down, and indeed, the question of speeding has always been a tricky one for the Safari.

For a first event, the 1953 Coronation Safari went off with remarkably few hitches. Some wrong turnings were taken by drivers due to main road re-alignment, but most of the route was well-known territory as it comprised African trunk roads. Very few competitors had done a route recce and even those who had were caught out by roadworks. The fastest car was the Chevrolet of John Manussis/John Boyes, though in the early sections in Kenya it had taken a wrong turning and was being led by one of the Class C entries, a Wolseley 6/80 driven by Col Grantham/Cliff Collinge. However, after leaving Nairobi for the southern loop, the Wolseley first broke its sump and then knocked its petrol tank out on to the road; the crew fixed both these minor problems and finished the rally with the petrol tank on the rear seat!

The most southerly point of the rally was Iringa, in Tanzania, which the competitors reached having driven twenty-eight hours non-stop except for re-fuelling, checking in at controls, and having the inside of the car sprayed for tsetse fly at the Tanzanian border. From there back to Nairobi there were 830 miles which were to be a hell of water and mud. Drivers used chains and other aids to get through, but spins and other dramas were frequent as they struggled to keep to their time schedules. Even Manussis put his Chevrolet off the road and Boyes rigged up some empty petrol cans to keep it afloat while he went for help to push it back on the road. In these conditions, cars with big engines and lots of torque were at an advantage as were cars with rear engines. The Tatra T-600 of D. P. Marwaha/Vic Preston had both and stormed through the mud to win Class C by just one minute from Morris Temple-Boreham’s Humber Hawk.

Although the Chevrolet was to record the fastest overall time for the course - some two hours, seventeen minutes quicker than any other finisher - the car with least penalty points was the Class A winning Volkswagen 1200 of Alan Dix/J. Larsen, which was only seventeen minutes away from its set time. This was an incredible performance as they had suffered a nasty accident some five hours before the finish during which the steering was bent and the co-driver had been thrown completely through the windscreen, breaking his nose and collecting two black eyes.

At the end of this first event, there was some dispute as to who had officially finished. The section in Tanzania of Korogwe- Tanga-Korogwe had been cancelled due to the extremely bad weather and was replaced by Nairobi-Gilgil-Nairobi, which meant that on arrival at Korogwe, the rally proceeded via Mombo and Voi to Nairobi and was then to cover the extra stretch to Gilgil and back. However, since to be a finisher you had to arrive at Nairobi within 10 per cent of the time taken by your class winner, the organizers decided that, as regards time, the rally had finished at Voi. This gave sixteen finishers, all of whom also covered the rest of the route, but eventually it was decided that all twenty- seven cars which reached Voi were to be classified as finishers. This sort of decision has always been a tricky one for the Safari where cars can run almost literally days apart and experience totally different weather conditions over the same section.

This first Safari had everything from dust to mud, and those who entered, finishers or not, loved every minute, while spectator interest had exceeded the organizers’ wildest hopes thanks in considerable measure to the East African Standard, newspaper, which sponsored the event and reported it fully and to the radio networks, both national and amateur, which followed every mile of the event.

For the second event, the average speed was lowered and ranged from 42 mph for Class A to 46 mph for Class D. There were three starting-points again, with Dar es Salaam replacing Morogoro, but there were also three compulsory halts during the rally totalling seven-and-a-half hours, reflecting the organizers’ concern with safety. There was no ‘Indianapolis start’ this time, but cars were sent off in numerical order at two-minute intervals with gaps of several hours between the classes. For instance at Nairobi, Class A went off at noon and Class D at four o’clock, but at Dar, this long time gap was to prove a bit too much as the early starters got through the horrific Ruvu section in the dry while the big cars caught all the rain which came after lunch. John Manussis was one of the unlucky ones and his Jaguar Mk VII only averaged 19 mph over the first 300 miles.

In their eagerness to rid the Safari of its ‘racing’ associations, the organizers had gone a bit too far and underestimated the capabilities of the cars, especially the small models. Despite starting from Dar, Jim Feeney’s Class B Peugeot 203 finished the rally unpenalized on the road, as did the similar cars of Jamal Din and Nick Nowicki, driving in their first Safari. In all, fourteen cars were unpenalized and at the finish in Nairobi there was an acceleration/braking test to decide the results. It was a pity that due to exceptionally large crowds this had to be held on a very short, wet strip of tarmac outside the City Hall. The Fiat 1100-TV of Menezes/Ribeiro, which had scraped in with no penalties after stopping for three and a half hours in Kampala for repairs, had no brakes left and failed the test. This left thirteen cars, separated by about three seconds after the test, and at first it looked as if British cars had won the day with the Neil and Donald Vincent Vauxhall Velox first and a Ford Zephyr driven by P. L. F. Hoosen/R. F.

Jennings second. Then it was announced that these two plus the Volkswagen of Brooks/Vest had been disqualified for exceeding the speed limit within Nairobi.

The winner therefore was the Volkswagen of D. P. Marwaha/ Vic Preston which by coincidence had started as number one. It had been lucky to finish the rally at all as towards the end it had broken a driveshaft spline, and had been limped in to the nearest town on a jury rig, where a young lady had been persuaded to lend the crew the shaft out of her car - all this at 6.30 a.m.! Volkswagen also won the manufacturer’s team prize, something they were to do another three times in the first twenty years’ history of the rally.

Unlike the first Safari, this had been less of an epic and twenty- five of the fifty starters finished, too many of them without penalty on the road section. This was not good enough, and for the following year, 1955, the average speeds once again rose. At the same time, proper time controls were established in nine places in addition to the start and finish which this time were at Nairobi for all competitors. The route was 500 miles longer, took in all three East African capitals, and had more rest halts including a six-hour stop in Nairobi between the northern and southern legs. There was still a time differential between the classes, but for the first time there was a specific period of lateness behind which a competitor might not fall in order to be classed as a finisher.

The fifty-eight starters included a couple of Model A Fords although most of the machinery was considerably more modern. Marwaha/Preston had swapped their Volkswagen for a Ford Zephyr, only to find that the Volkswagens made most of the running. Arthur Burton/Gus Hofmann were unpenalized on all but one section, where they lost three hours curing a serious engine malady, while T. F. Banks/R. G. Richardson came through the entire event without losing a single point. The Volkswagen of Bill Carwell/Norman Thomas lost four minutes in the mud of Tanzania, while Marwaha/Preston in the Ford dropped five with brake troubles, so it looked all set for a Volkswagen victory. However, points could also be lost by failing to cover two of the sections each of several hundred miles, at the same average speed, and here Banks’ Volkswagen lost two more points than the Zephyr while on final scrutineering it lost forty more. Thus victory went to Ford with Volkswagen 1-2-3 behind, earning them the team prize. Mar- waha and Preston could count themselves lucky for like the year before the winners had so nearly dropped out of the rally; a vulture had smashed through the windscreen of the Zephyr and Preston had to have splinters of glass removed from his eye at one of the rest halts.

For the first time there was a Safari Ladies’ Cup, which was presented by Lady McMillan and won by Mary Wright/June Burton in a Ford Zephyr after Mary Heather-Hayeg/Lucille Card- well had retired their VW with a cooked engine, the result of too much mud in the cooling intakes. The previous year only one lady competitor had finished the first Safari; she was Miss Hurst, a barrister, who drove a Mercedes 170 diesel.

The Safari was still suffering from growing pains, and the next three years were to prove the most painful. The 1956 event was held in some of the driest weather ever known and consequently the times set were too easy for many of the drivers. Although the number of time controls had been increased, the organizers had reverted to the idea of an overall average speed within each class, which in every case was lower than the previous year. This, combined with the fair weather, meant that the Safari had its highest- ever proportion of finishers with seventy-eight coming home out of ninety starters, thirteen of them unpenalized on the road sections. For the last time in Safari history the rally was settled on a tie- decider.

This was a standing-start lap round the tarmac Nakuru circuit, with the times achieved adjusted to a formula dependent on the cylinder capacity of the car. The Auto-Union 1000 of Eric Cecil/ Tony Vickers became the overall winner having made the best use of its front-wheel drive and short wheelbase on the narrow, twisty circuit. For Cecil, one of the instigators of the rally, this was some recompense for his disappointment in 1954 when he suffered a major accident in a Jaguar Mark VII with Chris Little. 1956 was the year in which Maurice Gatsonides, a former winner of the Monte Carlo Rally, finished third in his class driving a Standard Vanguard and it was his report of the rally which he carried back to Europe which led to recognition of the Safari by the Federation International de VAutomobile the following year.

Despite a much earlier start, the rally being run over the Easter holiday for the first time, heavy rain made the going tough all the way in 1957. A longer route was chosen, using more second-class roads, and the regulations called for the sealing of various components with penalties for any changes made along the route. The rally was dogged by controversy from the start when some local dealers refused to enter cars, complaining that they were paying for publicity but were not getting any aid from the organizers. However, the boycott was not total, and there were official teams from Simca, DKW and Goggomobil, while many other entries evidently had some assistance from behind the scenes.

Then, during the rally, it was reported that forty-five of the competing cars had exceeded the speed limit in the Tanzanian town of Tanga. The officials in Nairobi felt that such a reckless attitude to the future of rallying should be punished, and when all the competitors concerned arrived back in Nairobi at the end of the southern leg they were told they had been penalized. Despite the muddy going, six Volkswagen crews were still unpenalized at the time controls but all had been reported from Tanga. They promptly headed a mass protest to the stewards, worried that the regulations listed exclusion as the penalty for speeding, and pointing out that the speeds claimed to have been observed by the Tanga police were often in excess of the particular car’s maximum speed! Eventually all the penalties were scrubbed and the rally proceeded, though the fast forty-five had to pay their fines subsequently to the Tanga authorities.

On the northern leg the rain became worse and several parts of the route had to be cancelled as being impassable. At Kampala, Safari veteran Jim Feeney’s Peugeot 403 was leading by two minutes from Arthur Burton’s Volkswagen, these being the only two cars to cover the road round the back of Mount Elgon without getting stuck. The big problem for most people was to pass an ambulance stuck on what is now known as ‘Ambulance Hill’ and a dozen or so cars spent the night there in a vain effort to get through. Poor Feeney, having missed all the bother, lost the rally when a suspension arm bolt broke before the next control, and while he was mending it, the DKW of Tony Vickers became stuck alongside. Both cars were got going again but could not catch the Volkswagens which had used their rear-engine traction to pass the ambulance and take a comfortable lead. The final sections of the rally round Mount Kenya were cancelled and eventually only nineteen cars were classified as finishers with Arthur Burton/Gus Hofmann the winners in their Volkswagen and the Germans again taking the manufacturer’s team prize.

Most of the difficult sections were run without any time differential between classes in 1957, and the following year every section was run on scratch - a policy which has been adopted ever since. The route was shortened slightly, the northernTeg being run first, while the speeding penalty was set at 1 hour 40 minutes of lateness instead of exclusion. This time there was to be no outright winner, only class awards, of which there were to be three instead of the usual four, each class being named after an animal. The rain held off this time and the going became pretty fast with dust replacing mud as the main hazard and making overtaking a dangerous operation.

The only two cars unpenalized on the northern leg were the Ford Zephyrs of Vic Preston/Roy Springer and the Kopperud brothers, but Preston lost over an hour on the next leg with dirt in his petrol. No fewer than five cars came through the southern leg without penalty including the two Auto-Unions of Mike Armstrong/Morris Temple-Boreham and Tony Vickers/F. Ryce, the Peugeot 403 of Jim Feeney/Nick Nowicki and the John Man- ussis Mercedes 219. The Zephyr of Arne and Kaare Kopperud lost three minutes, and had there been an overall victor, it would have tied with Armstrong’s Auto-Union, which had dropped the same amount on the first leg.

But the performances of individual drivers fell into insignificance when Kopperud’s Zephyr and the class-winning Anglia 100E of Peter Hughes were penalized for having broken seals on their front suspension struts. The Ford drivers protested, and the stewards decided in their favour after coming to the conclusion that the parts had not been changed nor the seals tampered with. Then the Mercedes and Volkswagen entrants counter-protested, and this was heard by a supra-legal tribunal which decided to re-impose the penalties which in their opinion concerned broken seals only. The Ford drivers then appealed to the stewards of the Royal Automobile Club in London, and in late November the penalties were finally scrubbed, although by this time no one was really interested.

Unfortunately, no major rally seems to escape this sort of problem entirely, but it was particularly embarrassing to the Safari organizers as the rally had attracted eight overseas drivers, including ex-Monte Carlo Rally winners Ronnie Adams in a Mercedes-Benz 220 and Per Mailing in a Volvo P444, as well as two Australians and some French drivers from Madagascar. However, the affair did not prove to be a deterrent after all, and 1959 saw the first full-scale effort from overseas including works teams from Ford and Rootes, although one entry, a Riley 1.5 to be crewed by ex-winner Arthur Burton and journalist Peter Garnier, was not allowed to start as the car had been modified beyond what the Safari organizers would accept as Group 1. Rootes, under the guidance of Norman Garrad, entered three Hillman Huskies to be driven by Peter Harper, Paddy Hopkirk and Peter Jopp with local co-drivers, but Harper crashed and broke his arm and was taken to hospital by Jopp while Hopkirk ran out of time at Dar es Salaam. However, Rootes also had a Humber Super Snipe for Ronnie Adams/Jim Heather-Hayes, who finished.

Of the overseas entries the Ford team achieved the most success, with Denis Scott/Peter Davies and Edward Harrison/David Markham finishing second and third overall behind the victorious Mercedes 2x9 of Bill Fritschy/Jack Ellis. The winners had snatched victory from another Mercedes driven by Nick Thomas/David Lead who had experienced brake trouble just before the finish. Until that point, Thomas had lost only one minute on the damp southern leg, whereas Fritschy had dropped three minutes, the result of getting stuck on the infamous Mbulu section.

Some names cropped up in the 1959 entry list which were to become much better known in later years. For example, Bert Shankland was co-driving a Zephyr which retired with a broken spring, while Joginder Singh co-drove the Volkswagen of R. M. Patel, sponsored by the Moonlight Driving School, and Peter Hughes had Tommy Fjastad as co-driver in his Anglia which took fourth place in the same class.

In i960, the Coronation Safari became the East African Safari and inherited a full-time organizer. International cubic capacity classes were adopted in place of those based on price, and an additional class was opened for improved production cars and GT cars, though this was to receive little support. The previous year’s decision to use radioactive paint instead of mechanical seals to identify components had proved very successful and was continued, while the ballot for starting order was re-instated to prevent any class gaining an advantage over another.

The rally hit serious problems even before it had started as due to widespread flooding in Tanzania it had to revert to a very simple route using mostly main roads. However, these were sufficiently inundated to provide a severe test of man and machine and over half the eighty-four starters were out by the end of the southern leg back at Nairobi, one of the first cars to retire being the Ford Zephyr of Edward Harrison/David Markham, which holed its radiator. The official Rootes team of Rapiers lost Ronnie Adams/John Boyes with their radiator blocked by mud, while Paddy Hopkirk/Kim Mandeville and Nancy Mitchell/Mrs Johnny Bush also retired on the southern leg. Only Peter Harper/E. A. Perry survived to tackle the northern leg and they retired later with damaged suspension. The Rootes team manager, Norman Garrad, was widely quoted as saying that the rally was too rough!

With supreme optimism three of the new Morris Mini-Minors were entered, one driven by Peter Riley, but predictably all retired, though the car driven by Johnny Bush/G. Alexander did reach the end of the first leg. The new Ford Anglia 105E fared much better, and at the finish took the first three places in its class, with Peter Hughes/Dick Bensted-Smith and Jeff Uren/Mike Armstrong leading them home, while Bert Shankland drove an Anglia entered by an Arusha company and came fifth in the same class.

The rally leaders all the way were Bill Fritschy/Jack Ellis, who finished the tough course with a loss of only twelve minutes in their Mercedes 219. Continental cars certainly proved their worth on this occasion for second overall, only seven minutes behind, was the revolutionary - at that time - Citroen ID 19 crewed by Morris and Freda Temple-Boreham. Next were the Ford crew, Vic Preston/John Harrison in a Zephyr Mark II, who headed a victorious manufacturer’s team completed by Denis Scott/Leon Baillon and Cuth Harrison/Davies. This latter crew caused quite a sensation when their car collapsed on the final braking test outside

while Hermann hit a bank but lost no time. Aaltonen, meanwhile, had worked his way back up to fifth place ahead of Shankland’s Peugeot 504, but his rear suspension had suffered in doing so and he had to lose more time for repairs. Young Mehta, fully at home in his native Uganda, pulled up to within one minute of Hermann, but then lost seven minutes to him over Tot and Tambach, only to be presented with the lead when Hermann stopped too long at a service-point.

The final fling of the rally was round Mount Kenya, where mud made a change from dust on this generally dry event. Mehta became stuck here and lost fifty-two minutes against only forty- seven lost by Hermann, which effectively decided the rally. Porsche had lost Ake Andersson after the Kenyan border with no rear suspension, and now Zasada was to be stopped for fifty minutes on the last easy section into Nairobi with a blocked petrol pump which cost him third place. Robin Hillyar inherited it but then lost points at scrutineering, so it was the indefatigable Bert Shankland/Chris Bates who finally took third place. The big speed differential between the leading Datsuns and the rest of the field was highlighted by Mehta finishing in second place with two hours eight minutes less penalty than the third-placed Peugeot.

So there we have the modern Safari. A long, hard, high-speed drive on wild African roads which can provide both mud and dust as well as every imaginable hazard that a car and its crew could

hope to meet, with the possible exception of snow and ice. Long may it continue!

1953 No overall winner

Class A A. Dix/J. Larsen (VW 1200)

Class B J. Airth/R. Collinge (Standard Vanguard)

Class C D. P. Marwaha/V. Preston (Tatra T-600)

Class D J. Manussis/K. Boyes (Chevrolet)

Manufacturer’s prize Volkswagen

1954 Overall winner D. P. Marwaha/V. Preston (VW 1200)

Class A D. P. Marwaha/V. Preston (VW 1200)

Class B J. Feeney/J. Greenway (Peugeot 203)

Class C J. Airth/E. Temple-Boreham (Standard Vanguard) Class D F. Wharton/J. Richardson (Wolseley 6/80) Manufacturer’s prize Volkswagen

1955 Overall winner D. P. Marwaha/V. Preston (Ford Zephyr)

Class A T. Banks/R. Richardson (VW 1200)

Class B D. P. Marwaha/V. Preston (Ford Zephyr)

Class C D. Vincent/L. Savage (Vauxhall Velox)

Class D J. Boyes/R. Noble (Ford V8 Pilot)

Manufacturer’s prize Volkswagen

1956 Overall winner E. Cecil/A. Vickers (DKW)

Class A J. Stone/P. Hughes (Ford Anglia)

Class B E. Cecil/A. Vickers (DKW)

Class C N. Vincent/D. Vincent (Vauxhall Velox) Class D J. Boyes/R. Noble (Ford V8 Pilot) Manufacturer’s prize Simca Aronde 1300

1957 Overall winner A. Hofmann/A. Burton (VW 1200)

Class A A. Hofmann/A. Burton (VW 1200)

Class B M. Armstrong/E. Temple-Boreham (Fiat 1100 TV) Class C J. Feeney/Z. Nowicki (Peugeot 403) Manufacturer’s prize Volkswagen

1958 No overall winner

Impala Class T. Brooke/P. Hughes (Ford Anglia)

Leopard Class E. Temple-Boreham/M. Armstrong (Auto Union 1000)

Lion Class A. Kopperud/K. Kopperud (Ford Zephyr Mk 2)

Manufacturer’s prize Volkswagen

1958 was Great Seals Protest year; this was the sixth Coronation Safari slightly shorter course of about 2,900 miles, the protest meant that provisional results were not finally confirmed until November of that year, the longest delay in the history of the event.

Two African crews took part for the very first time, one entered by the Morris distributors and the other by Scuderia Archer.

The first factory entry was also received, this being P-444 model from the Norwegian branch A.B Volvo of Goteborg, Sweden.

95 starters at two minute interval led by three Mk11 Ford Zephyrs for the Preston/Springer car having drawn No1 the remaining team cars , as is still customary, took the succeeding numbers, a raised starting ramp was used for the first time.

Winner of Monte Carlo Rally Ronnie Adams was also included, who shared a Mercedes 220-S with Jim Heather-Hayes; an Australian co-driving Mercedes 190 with H. Bausch; W.Warwick also of Australia , who shared an Opel Kapitan with Peter Shepherd. Three women’s team had an entry too.

There was no outright winner in 1958 and the regulation stated that the event of ties awards would be shared. Clases were renamed and the largest one started first this time, with Northern leg taken first. There was no speed differential as between class and class .The mileage was 2900 odd.

The above mentioned Mercedes (No 27) of C.J Manussis/K.Savage) came second in Lion class with 700 points, out of 95 starters 54 finished. Three capital’s trophy went to Tanganyika.

1959 Overall winner W. Fritschy/J. Ellis (Mercedes 219)

Class A J. Feeney/R. Fisher (Peugeot 203)

Class B F. Ryce/A. Vickers (DKW)

Class C W. Fritschy/J. Ellis (Mercedes 219) Manufacturer’s prize Ford Zephyr

1960 Overall winner W. Fritschy/J. Ellis (Mercedes 219)

Class A No Finishers

Class B P. Hughes/R. Bensted-Smith (Ford Anglia)

Class C Joginder Singh/Jaswant Singh (VW 1200)

Class D Mr/Mrs E. Temple-Boreham (Citroen ID19) Class E W. Fritschy/J. Ellis (Mercedes 219) Manufacturer’s prize Ford Zephyr

1961 Overall winner J. Manussis/W. Coleridge/D. Beckett (Mercedes 220)

Class A S. Pritchard/J. Hickman (Renault Gordini)

Class B P. Hughes/B. Young (Ford Anglia)

Class C J. Valumbia/I. Bakhsh (Sunbeam Rapier)

Class D Z. Nowicki/I. Philip (Peugeot 404)

Class E J. Manussis/W. Coleridge/D. Beckett (Mercedes 220 SE)

Manufacturer’s prize Ford Zephyr

1962 Overall winner T. Fjastad/V. Schmider (VW 1200)

Class A Pat Moss/Ann Riley (Saab 96)

Class B M. Armstrong/E. Bates (Ford Anglia)

Class C T. Fjastad/V. Schmider (VW 1200)

Class D J. Greenly/V. Jennings (Hillman Minx)

Class E Z. Nowicki/P. Cliff (Peugeot 404)

Class F C. Collinge/J. Jeeves (Fiat 2300)

Class G G. Burgess/B. Younghusband (Ford Zodiac Mk 3) Manufacturer’s prize Peugeot 404

1963 Overall winner Z. Nowicki/P. Cliff (Peugeot 404)

Class A No finishers Class B No finishers

Class C P. Hughes/B. Young (Ford Anglia)

Class D No finishers

Class E Z. Nowicki/P. Cliff (Peugeot 404)

Class F W. Cardwell/D. Lead (Mercedes 220 SEb)

Class G A. Bengry/G. Goby (Rover 3 litre)

Manufacturer’s prize No team finished

1964 Overall winner P. Hughes/B. Young (Ford Cortina GT)

Class A E. Carlsson/G. Palm (Saab 96)

Class B T. Fjastad/J. Jasani (VW 1200)

Class C P. Hughes/B. Young (Ford Cortina GT)

Class D B. Shankland/K. Kassam (Peugeot 404)

Class E Mrs Cardwell/Mrs Lead (Mercedes 220 SEb) Class F Viscount Mandeville/P. Walker (Ford Mercury Comet)

Manufacturer’s prize Ford Cortina GT

1965 Overall winner Joginder Singh/Jaswant Singh (Volvo

PV544)

Class A No finishers

Class B M. Khan/B. Singh (VW 1200)

Class C V. Preston/E. Syder (Ford Cortina GT)

Class D Joginder Singh/Jaswant Singh (Volvo PV 544) Class E Viscount Mandeville/P. Walker (Mercedes 300 SE)

Class F No entries Manufacturer’s prize Peugeot 404

1966 Overall winner B. Shankland/C. Rothwell (Peugeot 404)

Class A No finishers

Class B J. Greenly/J. Dunk (Datsun P-411)

Class C Y. Preston/B. Gerrish (Ford Cortina GT)

Class D B. Shankland/C. Rothwell (Peugeot 404)

Class E J. Saunders/J. Wilson (Mercedes 220 SE) Manufacturer’s prize Ford Cortina GT

1967 Overall winner B. Shankland/C. Rothwell (Peugeot 404)

Class A Mr and Mrs Mayers (Saab Monte Carlo)

Class B H. Lionnet/P. Cliff (Peugeot 204)

Class C V. Preston/B. Gerrish (Ford Cortina Lotus)

Class D B. Shankland/C. Rothwell (Peugeot 404)

Class E Allison/Hempstead/Walker (Mercedes 230)

Class F No finishers Manufacturer’s prize Ford Cortina

1968 Overall winner Z. Nowicki/P. Cliff (Peugeot 404)

2. P. Huth/I. Grant (Ford Cortina Lotus)

3. Viscount Mandeville/S. Allison (Triumph 2000)

4. M. Armstrong/D. Paveley (Peugeot 404)

5. J. Singh/B. Smith (Datsun H130)

6. R. Ulyate/M. Wood (Ford Cortina GT)

7. Mrs Cardwell/Mrs Davies (Datsun Hi30) Manufacturer’s prize No team finished

1969 Overall winner R. Hillyar/J. Aird (Ford Taunus 20 MRS)

2. J. Singh/B. Bhardwaj (Volvo 142S)

3. J. Din/M. Minas (Datsun P510)

4. M. Armstrong/D. Paveley (Peugeot 404)

5. E. Hermann/H. Schuller (Datsun P510)

6. S. Zasada/M. Wachowski (Porsche 91 iS)

7. R. Randall/B. Parkinson (Datsun P510)

8. J. Greenly/N. Collinge (Datsun P510)

9. R. Aaltonen/H. Liddon (Lancia Fulvia 1300)

10. Z. Nowicki/P. Cliff (Peugeot 404)

11. J. Saunders/H. Peatling (Datsun P510)

12. J. Salt/T. Fjastad (Audi Super 90)

Manufacturer’s prize Datsun P510

1970 Overall winner E. Hermann/H. Schuller (Datsun 1600 SSS)

2. J. Singh/K. Ranyard (Datsun 1600 SSS)

3. B. Shankland/C. Rothwell (Peugeot 504)

4. J. Din/A. Mughal (Datsun 1600 SSS)

5. Miss G. Michaelides/L. Robinson (Volvo 122S)

6. Viscount Mandeville/S. Allison (Triumph 2-5 PI)

7. M. Kirkland/J. Rose (Datsun 1600 SSS)

8. R. Harris/P. Austin (Peugeot 504)

9. A. Esposito/R. Randall (Alfa Romeo Giulia)

10. Z. Nowicki/P. Cliff (Peugeot 504)

11. P. Shah/T. Singh (Datsun 1600 SSS)

12. A. Kuner/H. Sulieman (Datsun 1600 SSS) Manufacturer’s prize Datsun 1600 SSS

1971 Overall winner E. Hermann/H. Schuller (Datsun 240Z)

2. S. Mehta/M. Doughty (Datsun 240Z)

3. B. Shankland/C. Bates (Peugeot 504)

4. R. Hillyar/J. Aird (Ford Escort T/C)

5. S. Zasada/M. Bien (Porsche 91 iS)

6. V. Preston Jnr./B. Smith (Ford Escort T/C)

7. R. Aaltonen/P. Easter (Datsun 240Z)

8. H. Kallstrom/G. Haggbom (Lancia Fulvia 1600)

9. R. Ulyate/I. Smith (BMW 2002 TI)

10. P. Huth/J. McConnell (Peugeot 504)

11. H. Lionnet/P. Hechle (Peugeot 504)

12. R. Harris/P. Austin (Peugeot 504)

Manufacturer’s prize Datsun 240Z

1972 Overall winner H. Mikkola/G. Palm (Ford Escort RS1600)

2. S. Zasada/M. Bien (Porsche 91 iS)

3. V. Preston Jnr./B. Smith (Ford Escort RS1600)

4. R. Hillyar/M. Birley (Ford Escort RS1600)

5. E. Hermann/H. Schuller (Datsun 240Z)

6. R. Aaltonen/T. Fall (Datsun 240Z)

7. R. Harris/P. Austin (Peugeot 504)

8. T. Makinen/H. Liddon (Ford Escort RS1600)

9. B. Shankland/C. Bates (Peugeot 504)

10. S. Mehta/M. Doughty (Datsun 240Z)

11. Z. Remtulla/N. Jivani (Datsun 1600 SSS)

12. O. Andersson/J. Davenport (Datsun 1800 SSS)

13. B. Culcheth/L. Drews (Triumph 2-5 PI)

14. E. Walker/A. Levitan (Datsun 1600 SSS)

15. J. Hellier/I. Street (Datsun 1600 SSS)

16. F. Tundo/B. Field (Datsun 1600 SSS)

17. P. Neylan/D. Reynolds (Datsun 1600 SSS)

18. Miss A. Taieth/Mrs S. King/Datsun 1600 SSS) Manufacturer’s prize Ford Escort RS1600