Indians Trading in the Indian Ocean Regions

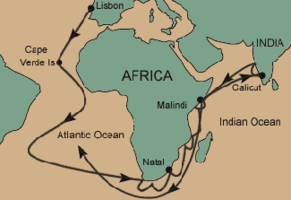

Indian merchant mariners, Arab seafarers, Chinese and Persian sailors, among other seafarers have all visited the East

African coastline stretching from the Horn of Africa to the port of Sofala in the south.

From the times of the Egyptian Pharaohs who hired Phoenician mariners to the pre-biblical era and after, these visitors came to trade on the African coast.

Although historians have not widely highlighted these visitors and the flourishing trade, its extensive evidence found on the East African Coast, known as Zeng

or Zenj as well as Azania, deep inland, and as far south as the ruins in Zimbabwe, is highly indicative of commerce long time before its colonial occupation.

The presence of Indians in East Africa is well documented in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea or Guidebook of Red Sea by an ancient Greek author written in 60

AD. The ancient Indian work the Puranas also mention the East African coast as well interior of Kenya as far as Lake Victoria, which was known as ’ Nil (Nile?) Sarover,’ Lake Nil, and knew the source

the of ‘Nil’ Nile.

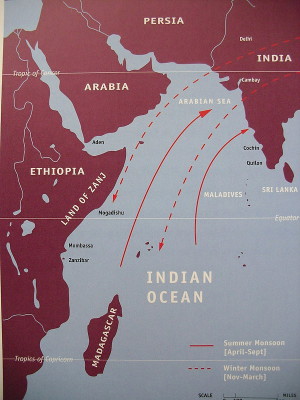

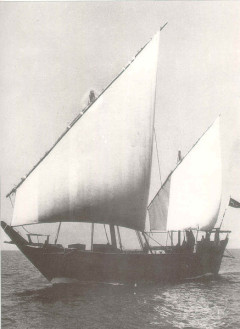

The Indian sea merchants from the Gulf of Kutch and further south on the west coast of India sailed their seagoing dhows, large wooden ships with a huge lateen

sails, aided by the alternating monsoon winds. The North East monsoon winds brought these merchant sailors across the Indian Ocean to the African east coast from December to March. After trading and

bartering, they returned using the reversed South West winds from June to September.

They sailed regularly to the Zenj Coast where they traded in cloth, metal implements, iron nails, copper wire, glassware, wheat, rice, sesame oil, raw sugar,

and salt.

On their return trip, they carried incense, palm oil, myrrh, gold, copper, spices, ivory, rhino horn, wild animal skins and ‘boriti’, mangrove poles. As time

went by, some Indians settled on the East African coast and set up their shops to trade in the merchandise from the dhows. These were the pioneer Indian traders on the East African coast. They were

exclusively traders, and not indentured workers.

The Indians have had ancient connections not just with the East African coastline but also its hinterland. The more intrepid Indian ‘nakhoda,’ skippers,

undertook caravans on foot safaris to the interior. They knew of places as far inland as Uganda. They also knew the Ruwenzori Mountains as ‘Chandragiri Shekhar,’ Moon Mountain or Mountains of the

Moon.

They had knowledge of the great inland lake, the ‘Neel Sarover’ Neel (Nile?) Lake, named much later as Victoria Nyanza, and even of its outlet the source of the Nile.

Much later European explorers encountered Indians settled in the interior married to the indigenous women.

Relics of Chinese pottery found in the ruins along the Kenya coast at Gedi and Bagamoyo in Tanganyika, now Tanzania, indicates that the Indian merchant sailors

who traded with China, in turn traded with the Gulf Arabs who then transhipped this cargo to the East African coast. These relics found in the great ruins of Zimbabwe, also indicates that the Indian

trade connection was an old thread in the history of the region.

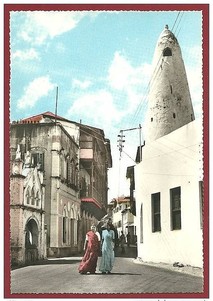

From the second to the eighth century, no major changes took place on the coast. However, with the rise of Islam, the Omani Arab rulers who came to the East

African Coast, turned the coastal settlements into city-states with the most important one being Zanzibar followed by Mombasa, Pate, Malindi, Manda, Tanga, and Kilifi. Using local stone and coral,

they built palaces, houses, and mosques to give Islamic atmosphere and culture to the coast, which endures to this day. The Indians traded along with the Arab traders in these city-states that

flourished undisturbed until the arrival of the Portuguese seafarer Vasco da Gama. Narrated by Kersi Rustom

Early contacts between Indians and East Africa go back at least 2000 years as we know of and when Vasco Da Gama arrived in Mozambique, Mombasa and Lindi in

1497, he was surprised at the number of Arabs and Indians he found there.

Obviously, Da Gama went to East Africa to find the sea-route to India, but many of today’s businessmen are happy to inform you that it was not Da Gama who discovered that route himself, but he was

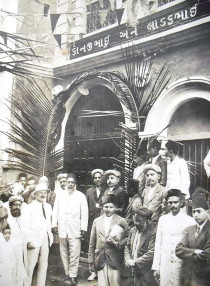

guided by the Indian Navigator Kanji Malam, who showed him the way to the South Indian Coast. “ you want to know who was the first member of our family to be in Africa and when? Well, his name is

Mohammed, he was known as “Kanji Maalim”. That name means’ master of the tille’, because in the language of Gujarat, which is where we Badalas are from, the word for tiller or ruder , is ‘sukhan’. He

was the pilot who showed Vasco Da Gama the way from Malindi to India.

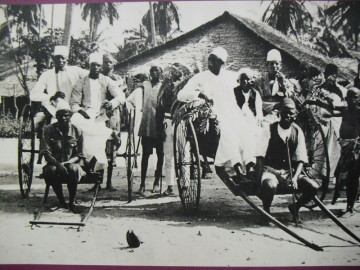

Most present day Indian families in East Africa have at least some memories of their (grand) parents’ migration and settlement histories. By far the most frequently heard one-liner were, ‘we came in Dhows’ and most came as young boys with little or no money seeking employment in one of the shop of family members or other community members. And then, after a while, that they started their own shops making long hours and working very very hard.

These above citations are from both well-known writers in Mr. Gijsbert Oonk and Ms. Cynthia Salvadori who both separately carried out their own researches

about the Asians in East Africa.

The Call of the Sea…1800-1880

Drawing largely on archival sources, The Call of the Sea examines the significant role played by Kachchhi traders in connecting Muscat and Zanzibar to the

thriving emporiums of Bombay and Mandvi. It provides an insight into the business environment and sophisticated sea-trade network that existed in the western Indian Ocean in the nineteenth

century.

The pro-trade policies of the Sultan of Muscat, Seyyid Said, and his tolerant attitude towards merchants acted as a catalyst. Cordial relations with the Arab

ruling class boosted the commercial prospects of the Kachchhis at Zanzibar in their competition with traders from other nations, Bhatias, Khojas,Bohras, Memons, and many other like Badhalas, Kharvas

who were deeply embedded within the rim of the Indian Ocean trade networks that included Arabs, East Africans and Europeans. Seafarers of the Kutchh (2006) by Simpson covers this topic too in

details.

Hindu and Muslims merchants of Kutchh had broadly similar business practices; they try to retain their specific identity.

It also purveys information about successful Kachchhi entrepreneurs like Thariya Topan, Jivanji Budhabhai and Sewa Haji Paroo to name a few. The powerful

entrepreneurial presence of Katchhi business firms throws light on the commercial expansion of these entrepreneurs outside India.

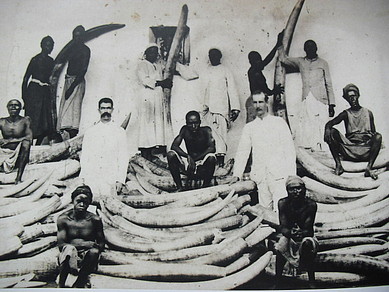

These entrepreneurs carried on a flourishing trade in ivory and cloves, among others. They also acted as bankers and financiers, and operated an effective

credit network for Indian mercantile communities. Mandvi acquired significance as the chief port of Kachchh, while the economies of Muscat and Zanzibar benefited from waves of migration of these

traders. In this context there is an illuminating case study of the dominant business house of Jairam Shivji in Zanzibar. The involvement of Kachchhi traders in the slave trade, which was once

important in the east African economy, is also brought into focus.

Depicting the early potential of the Indian diaspora prevailing in a competitive foreign milieu, this study will be useful to many and also students of history, international relations, and foreign trade, as well as those engaged in African or Gulf Studies.

In most European’s minds the Indians simply did not matter. When writing of East African history in general, the role of Indians is ignored or slighted. It is the British that get the credit for ‘pluck and determination’ building the Railways even when it is admitted that Indians suffered untold horrors.

Even classifying the architectural styles in Mombasa’s Old Town, the authors of the “Conservation Plan for Old Town” deliberately called the Indian Buildings ‘Traditional Mombasa houses”. The assumption was that every Indian was a ‘coolie’ unless you were of a Goan back ground (mostly educated clerks).

Most if not all prime geographical areas were also chosen for themselves and area controlled by the British Europeans for the Europeans. The lack of information about Indians is due not only to the non-Indians’ disinterest (and often hostility). It is due also to the Indians’ own lack of Interest in writing about themselves.

There are good reasons for this. Whereas most of the Europeans who came to Kenya came primarily to have a more adventuresome life (albeit often with extremely hard work) in a lovely land, the great majority of Indians came out of desperation, to try make a living. And whereas the European who settled or worked in Kenya came from a culture and class where writing a diary and publishing a book reminiscences were taken for granted, many Indians who came to Kenya were illiterate and those who were literate were not from a journal-writing culture. They recounted their adventure as oral history.

The presence of Indians in East Africa is well documented in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea or Guidebook of Red Sea by an ancient Greek author

written in 60 AD. The ancient Indian work the Puranas also mention the East African coast as well interior of Kenya as far as Lake Victoria, which was known as ’ Nil (Nile?) Sarover,’ Lake Nil, and

knew the source the of ‘Nil’ Nile.

The Indian sea merchants from the Gulf of Kutch and further south on the west coast of India sailed their seagoing dhows, large wooden ships with a huge lateen sails, aided by the alternating monsoon

winds. The North East monsoon winds brought these merchant sailors across the Indian Ocean to the African east coast from December to March. After trading and bartering, they returned using the

reversed South West winds from June to September.

They sailed regularly to the Zenj Coast where they traded in cloth, metal implements, iron nails, copper wire, glassware, wheat, rice, sesame oil, raw sugar, and salt.

Early contacts between Indians and East Africa go back at least 2000 years. And when Vasco

Da Gama arrived in Mozambique, Mombasa and Lindi in 1497, he was surprised at the number of Arabs and Indians he found there. Obviously, Da Gama went to East Africa to find the sea-route to India,

but many of today’s businessmen are happy to inform you that it was not Da Gama who discovered that route himself, but he was guided by the Indian Navigator Kanji Malam, who showed him the way to the

South Indian Coast.

“ you want to know who was the first member of our family to be in Africa and when? Well,

his name is Mohammed, he was known as “Kanji Maalim”. That name means’ master of the tille’, because in the language of Gujarat, which is where we Badalas are from, the word for tiller or ruder , is

‘sukhan’. He was the pilot who showed Vasco Da Gama the way from Malindi to India.

Most present day Indian families in East Africa have at least some memories of their (grand)

parents’ migration and settlement histories. By far the most frequently heard one-liner were, ‘we came in Dhows’ and most came as young boys with little or no money seeking employment in one of

the shop of family members or other community members. And then, after a while, that they started their own shops making long hours and working very very hard.

These above citations are from both well-known writers in Mr. Gijsbert Oonk and Ms. Cynthia Salvadori who both separately carried out their own researches about the Asians in East Africa.

Asians In East Africa - A Brief History

The easternmost region of Africa consists of countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. This region also consists of some well-known lakes and mountains: the fresh water Lake Victoria, Lakes Albert and Tanganyika, and Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro — the two tallest peaks in the region.

Click on Photo for History of the Asians in East Africa

In the British Empire, the labourers, originally referred to as "coolies", were indentured labourers who lived under conditions often resembling slavery. The system, inaugurated in 1834 in Mauritius, involved the use of licensed agents after slavery had been abolished in the British Empire. The agents imported indentured labour to replace the slaves. The labourers were however only slightly better off than the slaves had been. They were supposed to receive either minimal wages or some small form of payout (such as a small parcel of land, or the money for their return passage) upon completion of their indentures. Employers did not have the right to buy or sell indentured labourers as they did slaves.

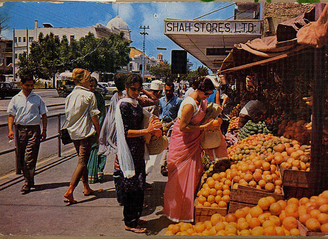

Of the original 32,000 contracted laborers, after the end of indentured service about 6,700 stayed on to work as dukawallas,[Note 1] artisans, traders, clerks, and, finally, lower-level administrators. Colonial personnel practices excluded them from the middle and senior ranks of the colonial government and from farming; instead they became a commercial middleman and professionals, including doctors and lawyers.

It was the dukawalla, not European settlers, who first moved into new colonial areas. Even before the dukawallas, Indian traders had followed the Arab trading routes inland on the coast of modern-day Kenya and Tanzania. Indians had a virtual lock on Zanzibar's lucrative trade in the 19th century, working as the Sultan's exclusive agents.

Between the building of the railways and the end of World War II, the number of Indians in East Africa swelled to 320,000. By the 1940s, some colonial areas had already passed laws restricting the flow of immigrants, as did white-ruled Rhodesia in 1924. But by then, the Indians had firmly established control of commercial trade — some 80 to 90 percent in Kenya and Uganda was in the hands of Indians — plus some industrial activities. In 1948, all but 12 of Uganda's 195 cotton ginneries were Indian run.

Many Parsis settled on Zanzibar to work as merchants and civil servants for the colonial government. They formed one of the largest Parsi communities outside of India, a community that survived until the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964. Indians in Zanzibar founded the one locally-owned bank in all of East Africa, Jetha Lila, which closed after the Revolution when its customer base left.

Click on Photo

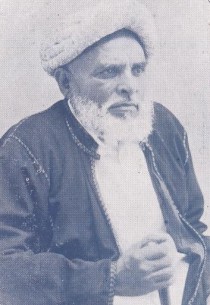

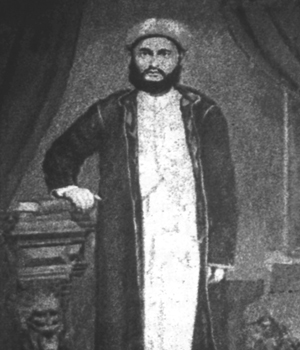

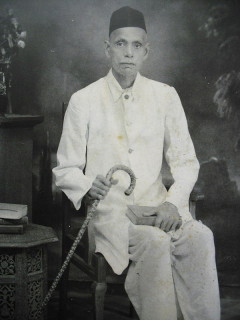

Sir Tharia Thopan (1823-1891)

About Tharia Thopan, the European Explorer H.M. Stanley writes in his book, ‘How I found Livingstone,’ that, ‘one of the most honest men among all individuals, white or black, red or yellow, is a Mohammetan Hindi called Tharia Topan(…) he had become a proverb for honesty and strict business integrity. He is enormously wealthy, owns several ships and dhows, and is a prominent man in the councils of Seyyid Burgash.

Maharao Khengar I (1510-1585), the ruler of Kutchh is credited to

have flourished Mandavi in Kutchh with a port during 16th century. The Bhatia caste of Hindus in Thatta, Sind was a famous merchant class. For promoting trade in Kutchh, Maharao Khengar I invited a

certain Bhatia Seth Topan in Bhuj and sought his advice. With the suggestions of Seth Topan, the city of Mandavi with a port was built with massive sum. Seth Topan employed expert carpenters of Sind

to build ships.

He imported wood fromMalbar and formed the firnances in Bhachao to prepare iron-nails. He was thus responsible to lay foundation of trade and ship building in Kutchh. He also built many temples in Mandavi. In those days, the Ismaili vakil, Sayed Pir Dadu (1474-1596) had come in Kutchh from Sind in 1587 and converted a large number of the Hindus, including Seth Topan in the time of Rao Bharmal I (1585-1631). The descendant of Seth Topan continued the business in Kutchh for about two centuries, but the later generations began to reduce in extreme poverty.

Among the greatest Ismaili heroes of East Africa was Varas Sir Tharia Topan, one of the descendants of Seth Topan, who coming from India as a small boy and working for the firm, M/S Jairam Shivji for 6 shillings per month, rose to be known as The King of the Ivory Trade.

He was born on Wednesday, September 21, 1823 in Lakhpat, Kutchh and was a son of a small vegetable seller. No facility of the formal educational subsisted in Lakhpat, which made him unlettered. He worked with his father as a helper. When he was 12 years old, he noticed one evening a playmate stealing money from a shop. He caught the boy in the street, recovered money and as he went to the shop to return it, the owner who, without hearing anything, raised a hue and cry himself accused him of the theft. Poor Tharia was severely belabored by the crowd, which had gathered around him. Fearing the worst and not daring to face his parents, he fled and jumped into the sea, got into the nearest vessel he saw, and took refuge amidst the cargo.

The fear of the thrashing he received, sent him to sleep and when he woke up he found that the vessel was on high seas and himself a stowaway. Compelled by hunger and thirst he revealed himself to the crew, and the Tandel, who took compassion on him when he related incidents leading to his refuge in the vessel, tended to his needs as there was no chance of being restored to his parents.

This vessel landed him in Zanzibar, where an accountant, who was working with the prominent Indian firm of Jairam Shivji of Mundra, Kutchh and knew his father, befriended him and got him the job of a garden sweeper in the house of Ladha Damji, the owner of the firm. It is an admitted fact that most of the Indian Ismailis came in Africa with industry in their blood, business in their brains and immense calibre to labour in their muscles, but with empty pockets. This illustration richly emanated in the personage of Tharia Topan.

Cont: Linked on Photo/http://www.ismaili.net/Source/mumtaz/Heroes1/hero099.html

http://www.pambazuka.org/en/category/books/66789/print

http://records.ancestry.com/Tharia_Topan_records.ashx?pid=174921271

http://www.dewani.ca/af/communal/zanzibar_khoja_shia/zanzibar_khoja_shia.htm

Prominent Indians

THARIA TOPAN, SIR (1823-1891)

Allidina Visram(1851-1916)

http://ismailimail.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/allidina-visram-pgs.pdf

http://ismailimail.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/alidina-rashid-khamis.pdf

Uganda Asians by Vali Jamal

https://ismailimail.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/alidina-rashid-khamis.pdf

Khojapedia

KhojaPedia is an online encyclopedia that details the socio-religious matters of the Khoja Shia Ithna Ashari Muslim community. It seeks to document and preserve the history and rich heritage of this community, including the community’s remarkable spiritual migration from one faith to another through maintaining the spirit of unity and organisation.

The principles of this endeavour are :

• Objective and reliable research through credible sources

• To promote an empathy with the faith, sacrifice, journey,

dedication, culture, heritage, identity and unity of the community

Allidina Visram

http://khojapedia.com/wiki/index.php?title=Allidina_Visram

The Three Kings Without Crowns

“I Wish I’d Been There”

By Mohib Ebrahim

http://simerg.com/special-series-i-wish-id-been-there/the-three-kings-without-crowns/

KhojaPedia

is an online encyclopedia that details the socio-religious matters of the Khoja Shia

Ithna Ashari Muslim community. It seeks to document and preserve the history and rich heritage of this community, including the community’s remarkable spiritual migration from one faith to another

through maintaining the spirit of unity and organisation.

The principles of this endeavour are :

• Objective and reliable research through credible sources

• To promote an empathy with the faith, sacrifice, journey, dedication, culture, heritage, identity and unity of the community

http://khojapedia.com/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page

Haji Paroo Pradhan

Omani Sultans banked on Kutchi moneybags

AHMEDABAD: The sultans of Oman and Zanzibar heavily banked on Kutchi moneybags. Many of them were in debt of banker-merchant from Mundra, Jairam Shivji.

After the death of Jairam Shivji in 1867, the amount of debt which the Sultans owed him stood at 600,000 dollars. A large number of European explorers also depended on the financial assistance of

Gujarati banker-merchants like Jairam.

"Jairam, a Kutchi Bhatia, had a consolidated trading and banking network between Mandvi, Mundra, Bombay, Muscat and Zanzibar in the 18th and 19th centuries. After his death, the amount of debt which

the Sultans owed him had reached such a magnitude as to lead the British consuls to intervene in the matter . The issue was finally settled with the help of John Kirk, political agent of Zanzibar,

when the debt was reduced to 200,000 dollars," writes former Gujarat University professor Shirin Mehta in the book 'Gujarat and the Sea' .

The Ismaili Imami Shiah Khoja in East Africa

Before the Colonial Period

Muslim Cultures beyond the Aperture: An East African Photo-Story Illuminated by First-Hand Accounts

In: Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World

In: Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World

Author: Nasira Sheikh-Miller

Online Publication Date: 09 Feb 2021

Introductory Background and Context

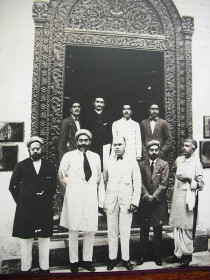

This paper is based on fieldwork drawing upon first-hand accounts from professional photographers, their family members as well as patrons of photography discussing their photographic collections (please see Table 1). These individuals were part of the South Asian diaspora to East Africa whose ancestors travelled from India via the Indian Ocean trade routes, and for the most part from the nineteenth century onward.

https://brill.com/view/journals/mcmw/1/1-2/article-p150_7.xml?language=en

Click on Photo

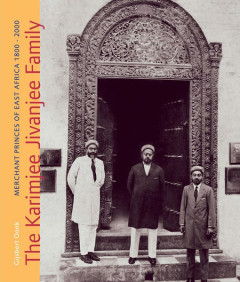

Gijsbert Oonk, the author, starts the book (The Karimjee Jivanjee Family: Merchant Princes of East Africa 1800–2000) with an insert of a family tree. This becomes a very necessary tool for readers as we weave through the journey of the prominent Karimjee Jeevanji family on the east coast of Africa. The author is a senior associate professor of non-western history at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. He has published various books and numerous articles on the history of the Indian Ocean region.

A story of South Asians in Africa

Review of ‘The Karimjee Jivanjee Family: Merchant Princes of East Africa 1800–2000’

Fatma Alloo

http://www.pambazuka.org/en/category/books/66789/print

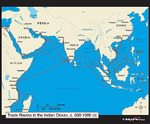

Migration Of South Asians In East Africa

If we look at the Map of the Indian Ocean it is not surprising that there was a lot of trade between West India, the Arab countries and East Africa.

Early contacts between Indians and East Africa go back at least 2000 years. And when Vasco Da Gama arrived in Mozambique, Mombasa and Lindi in 1497, he was surprised at the number of Arabs and Indians he found there. Obviously, Da Gama went to East Africa to find the sea-route to India, but many of today’s businessmen are happy to inform you that it was not Da Gama who discovered that route himself, but he was guided by the Indian Navigator Kanji Malam, who showed him the way to the South Indian Coast.

“ you want to know who was the first member of our family to be in Africa and when? Well, his name is Mohammed, he was known as “Kanji Maalim”. That name means’ master of the tille’, because in the language of Gujarat, which is where we Badalas are from, the word for tiller or ruder , is ‘sukhan’. He was the pilot who showed Vasco Da Gama the way from Malindi to India.

Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean before the Portuguese (Royal Asiatic Society Books) by a leading Scholar G.R. Tibbetts. Ibn Majid became famous in the West as the navigator who helped Vasco da Gama find his way from Africa to India, however, the leading scholar on the subject, G.R. Tibbetts, disputes this claim. Ibn Majid was the author of nearly forty works of poetry and prose.

Most present day Indian families in East Africa have at least some memories of their (grand) parents’ migration and settlement histories. By far the most frequently heard one-liner were, ‘we came in Dhows’ and most came as young boys with little or no money seeking employment in one of the shop of family members or other community members. And then, after a while, that they started their own shops making long hours and working very very hard.

-In 1873, Sir Bartle Frere writes, not without admiration, about Indians in Zanzibar’ Arriving at his future scene of Business with little beyond credentials of his fellow castemen, after perhaps a brief apprenticeship in some older firms, he (the Indian entrepreneur, G.O) start a shop of his own with goods advanced on credit by some large house, and after a few years, when he has made a little money, generally returns home to marry, to make fresh business connections, and then comes back to Africa to start all over again, on a large scale.

WHY HAVE THE SUNNI PUNJABI MUSLIMS CHOSEN THEUNDESIRABLE PATH OF EXCLUSIVENESS?

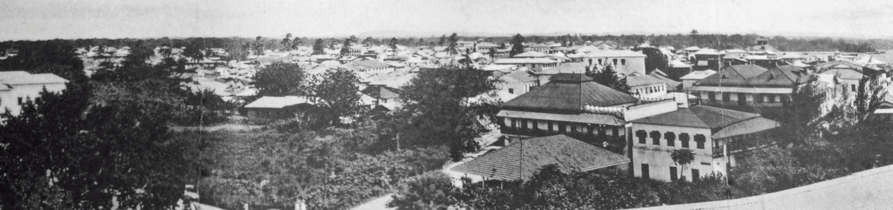

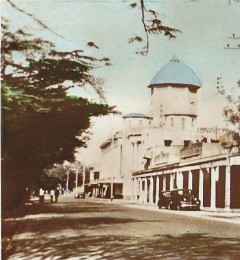

Mombasa various History:

http://www.sikh-heritage.co.uk/heritage/sikhhert%20EAfrica/nostalgic-Mombasa.html

Asian African Heritage Trust.

Welcome and Overview

It has been recognized that the presence of peoples from the Indian sub-continent in East Africa goes back well over three thousand years. The presence of peoples from Eastern Africa in India is also of long duration.

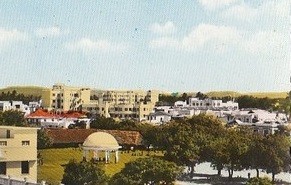

Many Asian African families have been settled on the Coast, Lamu, Pate, Malindi, Mombasa, Pemba, Zanzibar, Bagamoyo and Dar-es-Salaam from the 1820s and earlier; but the development of our Asian African minority as we know it today emerges from the 1880s.

Copyright 2012 Asian African Heritage Trust. All rights reserved

http://www.asianafricanheritage.com/index.htm