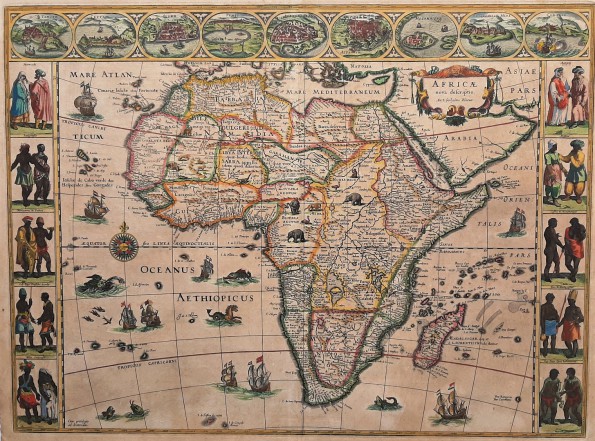

Start of European slave trading in Africa.

Conquerors: How Portugal Seized the Indian Ocean and Forged the First Global Empire with other Europeans..

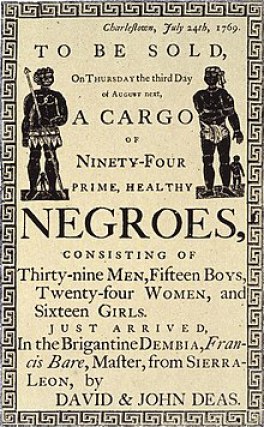

First and foremost slavery in whatever form was and is a despicable act that has been thrusted upon humanity to this day.

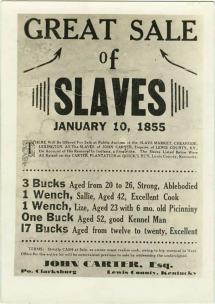

Various forms of slavery, servitude, or coerced human labour existed throughout the world before the

development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade as illustrated below, historian David Eltis narrates.

Before 1400: Slavery had existed in Europe from classical times and did not disappear with the collapse of the Roman Empire. Slaves remained common in Europe

throughout the early medieval period. However, slavery of the classical type became increasingly uncommon in Northern Europe and, by the 11th and 12th centuries, had been effectively abolished in the

north. Nevertheless, forms of unfree labour, such as villainise and serfdom, persisted in the north well into the early modern period.

In Southern and Eastern Europe, classical-style slavery remained a normal part of society and economy for longer. Trade across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic seaboard meant that African slaves began to be brought to Italy, Spain, Southern France, and Portugal well before the discovery of the New World in 1492.

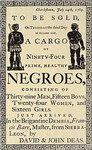

1441: Start of European slave trading in Africa. The Portuguese captains Antão Gonçalves and Nuno Tristão capture 12 Africans in Cabo Branco (modern Mauritania) and take them to Portugal as slaves.

"Most studies and textbooks on the slave trade focused on the 18th and 19th centuries, a time when the slave trade had become the main activity in Black Africa

(...) This historical approach has always avoided an analysis of the military and other means deployed by European slave traders in the 16th and 17th centuries to defeat African kings and elites who

resisted, and to put docile and corrupt leaders in their place.

Thus, this image of Africa selling its own children has always been based on a lack of knowledge of the particularly brutal means put in place by Europeans to demolish empires that were

prosperous, to exterminate any resistance to invaders ' Rosa Amelia Plumelle-Uribe “Traite des Noirs; Traite des Blancs”, pages 138-139.

If your own so called discoverers were of a pre-conceived notion or mindset in enslaving the indigenous people that they encounter, it is obvious what discovery was all about

!

Ancient Egyptian culture flourished through adherence to tradition and their legal system followed this same paradigm.

Many other places in Africa too had their laws under their own Kingdoms, some notable pre-colonial states and societies in Africa include the Ajuran Empire, D'mt, Adal Sultanate, Alodia,

Warsangali Sultanate, Kingdom of Nri, Nok culture, Mali Empire, Bono State, Songhai Empire, Benin Empire, Oyo Empire, Kingdom of Lunda (Punu-yaka), Ashanti Empire, Ghana Empire, Mossi Kingdoms,

Mutapa Empire, Kingdom of Mapungubwe, Kingdom of Sine, Kingdom of Sennar, Kingdom of Saloum, Kingdom of Baol, Kingdom of Cayor, Kingdom of Zimbabwe, Kingdom of Kongo, Empire of Kaabu, Kingdom of Ile

Ife, Ancient Carthage, Numidia, Mauretania, Buganda Kingdom, Aksumite Empire....etc.

In the 14th century, Arab traveller Ibn Battuta said about the city of Kilwa in Tanzania, in the black Swahili civilization, that it was the most beautiful city in the world. So that’s what Europeans found when they arrived in Africa.

The Swahili city-states steadily grew and prospered, and were a major world economic power by the 1400’s. Although the city-states were famous throughout

Africa and Asia, no European countries knew of them.

In fact it was with these words that Pope Nicholas V confirmed; on 8 January 1454, the authorization given to Portugal to begin the European slave trade and the destruction of

Africa.

His successor Pope Calixtus III, in 1456, specified “From the whole Guinea and beyond to India. It was therefore within the framework of an alleged

evangelizing mission that the Portuguese entered a rich and civilized Africa with their missionaries. The Europeans thus left descriptions of the civilizations they were about to destroy.

In 1482, the Portuguese entered the Kongo Empire, which at that time was under the reign of Nzinga a Nkuwu. The King, through the legendary African hospitality, was not cautious enough about them.

Thanks to the firearms that the Africans did not have, the Portuguese, then an emerging power after being re-civilized by the Blacks of North East Africa and the Arabs, brutally changed the course of

the African history.

At the death of Nzinga a Nkuwu, his son Mpanzu a Kitima, hostile to Europeans and rejecting Christianity, was crowned Mwene Kongo (Emperor of the Kongo).

The Portuguese then mounted an insurrection to install his brother Nzinga Mbemba, converted under the name of Afonso I. King Mpanzu was killed on the battlefield as he faced this coalition. Afonso

became Mwene Kongo.

The destruction of Kongo dia Ntotila commenced (the Kongo Empire).

You can imagine the surprise, then, of Portuguese captain Vasco da Gama when in 1498 he came upon bustling port cities such as Sofala, Kilwa, Mombasa, and Malindi as he sailed up the Eastern Coast of

Africa. He and his crew were welcomed by most of the cities they visited, although neither his ships nor the European items they attempted to trade were of much interest in the East African

city-states.

Vasco da Gama did eventually reach India with the help of an Indian navigator from Malindi named Kanji Mallam.

In 1499, da Gama returned to Portugal and told the king and queen, who had sponsored his voyage, everything that he’d seen, including the shiploads of gold, ivory, porcelain, silk, and cotton being

bought and sold in the port cities along the eastern coast of Africa.

In 1505; the Portuguese built a fort in Sofala (Mozambique). Like in Kongo, the strategy was to enter the Empire through religion. The first missionaries

arrived on the banks of the Zambezi around 1560; and after a brief conversion to Christianity, the emperor - who had obviously understood what was at stake - had the missionary Gonzalo da Silveira

killed. The Portuguese attacked the hinterland.

The destruction of the Mwene Mutapa Empire (Zimbabwe) had begun.

The organization of the slave trade was structured to have the Europeans stay along the coast lines, relying on African middlemen and merchants to bring their victims to be sold.

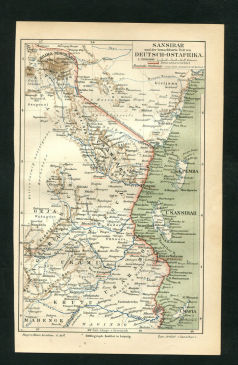

During the Age of Exploration, the Portuguese Empire was the first European power to gain control of Zanzibar, and kept it for nearly 200 years. Vasco da Gama's visit in 1499 marked the beginning of

European influence.

Louise Marie Diop-Maes said that: “After looting ships around Zanzibar in 1503, the Portuguese attacked Kilwa in 1505 and began building a fort. The same year

they threatened Mombasa, which resisted. With the help of African allies, the inhabitants fought against the Portuguese in the alleys of the city all the way to the King's palace. Having stormed the

palace, the Portuguese forced the King to surrender. The city was ransacked and burned down. Further north, Barawa suffered the same fate in 1528.

The destruction of the Swahili and Somali Kingdoms were the targets.

In 1503 or 1504, Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire and Slave trading in the area commenced on a commercial scale across the Indian Ocean and beyond

as the Portuguese were now the force that was bulldozing all city-states and stealing all the wealth and resources of the region and the area, thus the introduction and the beginning of taxation

emerged as it is known today.

The Portuguese government took immediate interest in the Swahili city-states. They sent more ships to the eastern coast of Africa with three goals: to take anything of value they could find, to

force the kings of the city to pay taxes to Portuguese tax collectors, and to gain control over the entire Indian Ocean trade.

Mombasa was attacked again. After 4 months of occupation, the Portuguese razed the city to the ground. In 1569. Mombasa was repopulated.

In fact there is much more history between Oman and the Portuguese, The Portuguese took over Muscat on 1st April 1515, and held it until 26th January 1650. Portugal dominated the region around Muscat

and beyond between 1507 and 1650 too.

(Click for :The Swahili Coast and Indian Ocean Trade).

Between 1500 and 1850, European traders shipped hundreds of thousands of African, Indian, Malagasy, and Southeast Asian slaves to ports throughout the Indian

Ocean world. The activities of the British, Dutch, French, Spanish, Portuguese traders… etc … who operated in the Indian Ocean demonstrate that European slave trading was not confined largely

to the Atlantic but must now be viewed as a truly global phenomenon. Richard B. Allen’s magisterial work dramatically expands our understanding of the movement of free and forced labour around the

world.

Drawing upon extensive archival research and a thorough command of published scholarship, Allen challenges the modern tendency to view the Indian and Atlantic

oceans as self-contained units of historical analysis and the attendant failure to understand the ways in which the Indian Ocean and Atlantic worlds have interacted with one another. In so doing, he

offers tantalizing new insights into the origins and dynamics of global labour migration in the modern world.

Turn of the 16th century saw all these International consortiums in East India Company, Austrian East India Company, Dutch East India Company and other

European countries such as the Spanish, Portuguese, Germans, Belgians, Dutch …etc all traded commercially in Slave trade as well as other goods, …

Residual numbers too of the slaves ancestry is apparent in the Mediterranean world, especially in Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, Greece, Imperial Rome and the Islamic societies of the Middle East and

North Africa”, India, Pakistan, Siri Lanka, China too…

What was so different about the Colonial legacy in terms of European Political and religious aspect that took shape at a latter part of period as time went by, adding larger conversion to

Christianity at a significant scale happened and was part and parcel of turning them into conforming beings even though the very indigenous people were looked upon as second or third class citizens

on their very own soil that they lived on, was it time that had changed the slave demographics and slavery trade was looked latterly inversely by the masters in a different light due to less call on

demand by overseas shipments claims and to now re-strategize to look into colonizing Africa as they did India and many other?

Various forms of slavery, servitude, or coerced human labour existed throughout the world before the

development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade as illustrated above. As historian David Eltis explains, and reiterated

“almost all peoples have been both slaves and slaveholders at some point in their histories.” Still, earlier coerced labour systems in the Atlantic World generally differed, in terms of scale, legal

status, and racial definitions, from the trans-Atlantic chattel slavery system that developed and shaped New World societies from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

In 1503 or 1504 seen Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire as explained earlier and Slave trading as well as other mercantile trade commenced on a commercial scale across the Indian Ocean,

South Africa and beyond, this had furthered introduced and added more scope to the already ongoing slave trade that was already in force in the Atlantic and therefore dove tailed into the existing

slave trading now with the introduction of the East African region with the ongoing Atlantic Slave Trade on the other side of Africa, that continued commercially into the 17th century” in fact

history further goes on and talks about 'The spice of slavery'

During the start of the 15th century Slave Trade between West Africa and across Europe, the North, the Atlantic to the Americas and West Indies had already

started taking shape on a supply demand basis, distributing the growth and demands of the discovery of the New World in 1492.

During the Age of Exploration, the Portuguese Empire was the first European power to gain control of Zanzibar, and kept it for nearly 200 years. Vasco da

Gama's visit in 1499 marked the beginning of European influence in or around whole of African coastal regions.

By this time “The transatlantic slave trade that had begun in or around the 15th century was in full force by 16th Century and was already shaping New World societies at a phenomenal rate across the

Atlantic and towards the West and into the Americas. Historically the Portuguese and other Europeans who already had vested lucrative interests in exploring the West Coast of Africa and later in the

16th Century expanded into not just the Kongo, East Africa but India, Malabar Coast, on the South East African coast at Delagoa Bay, and at the Nicobar Islands and beyond.

Although at first the number of enslaved Africans taken was small. In about 1650, however, with further development of plantations on the newly colonised Caribbean islands and American mainland and

other occupied colonization, the trade grew and expanded along the coasts of the Zeng (East African coasts), many Islands in the Indian Ocean as well as South Africa.

East Africa was now a focal point of the Indian Ocean and beyond...with now the emergence of Portuguese dominance (1500-1698CE) as per article… African Democracy Encyclopaedia Project clearly

states…… Conquerors they wanted to be, Portugal seized the Indian Ocean and forged the First Global Empire.

Various forms of slavery, servitude, or coerced human labour existed throughout the world before the

development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade as illustrated above, when the issue of who was the primary seller of Africans in the slave markets is discussed, majority of us are often in denial,

embarrassed to admit that their ancestors especially the clan chiefs sold people for a song-as cheap as possible. As historian David Eltis explains, and reiterate

that “almost all peoples have been both slaves and slaveholders at some point in their histories.”

Still, earlier coerced labour systems in the Atlantic World generally differed, in terms of scale, legal status, and racial definitions, from the trans-Atlantic chattel slavery system that

developed and shaped New World societies from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

Ansu Datta (From Bengal to the Cape - Bengali Slaves in South Africa 2013) p 19 - "...studies of transoceanic trade suggest that slaves hardly played a part in

the export trade from Bengal at that time [1665-1721]. As far as Africa is concerned, it seems that Bengali slaves who were brought to the Cape came mostly by way of Batavia." the East Indies

(31.47%), Ceylon/Sri Lanka (3.1%), Mozambique, Madagascar and the East African coast (26.65%), Malaya (0.49%) Mauritius (0.18%)…etc

One does not need to look too deep, it is evidently clear….South America, North America, West Indies and all over and across the Atlantic Ocean slaves were

shipped in millions, not just from India, East Indies, West Africa, East Africa, North Africa but many other places too that were under colonialism or of foreign occupancy.

Portuguese and their allies in Zimba tribe uprooted and ruled settlements, Coastal Towns and any other that came in their way. All the work of the

interior was carried out by this brutal tribe in capturing innocent men, women and children as slaves and brought to the Eastern Coast, there was also an attack by this tribe as far north as

Mombasa.

Portuguese later with the aid of Segeju tribe proceeded to make war on the Zimbas whom they entirely over threw.

In 1650 Omanis Arabs threw out the Portuguese Colonials from Oman and Muscat and later Zanzibar, Pemba and Mombasa, much war fare continued between the years 1660-1700 practically driving the

Portuguese out of most of East African possession, only to be left with Mozambique.

The Portuguese reasserted from 1727-1729 after which they were driven out for the last time, their assistance from Portuguese in India was destroyed by hurricane across the Indian Ocean.

Western Europe not only corrupted the slave/servility systems in Africa they also caused the Arab slave boom in the 19th century (Arab' is not a racial group),

this was mainly due to the fact in 1698, two years short of the 18th century, Zanzibar fell under the control of the Sultanate of Oman, which started and developed an economy of trade and cash crops,

with a ruling Arab elite and a Bantu general population.

Slave trade and other commercial trade carried on, it was now a residual number to the norm that was already two century old trade and proportionally of other trade as well as Slave trading that was

commercially started by the Portuguese in the region.

And most critical was Europe’s continuation of the African Holocaust up through colonialism, apartheid, neo-colonialism and the current exploitation of

Africa’s resources. These events are not disconnected, although attempts are made to dichotomize these realities.

Zanzibar became part of the overseas holdings of Oman, falling under the control of the Sultan of Oman.

The Omani set up trading companies in Zanzibar in the 18th century, ending nearly 200 years of Portuguese dominance on the island and also nearby smaller

islands that were used as holdings.

In 1832 the greatest Arab ruler, Said bin Sultan bin Ahmed, better know as Seyyid Said, a grandson of Ahmed bin Sa’id, the founder of the Al-Busa’id dynasty, decided to make Zanzibar the capital of

his dominions in the place of Muscat. He was mainly concerned to extend and to consolidate the influence and the commercial interests of Zanzibar along the coast of East Africa and inland to the

Great Lakes, these were un-renowned and seen as pioneers of exploration in East Africa and thus the Europeans explorers followed their trails and to seek beyond them.

As far back as 1822 Seyyid Said had already signed a Convention with the British government for “the perpetual abolition of the slave trade between the

dominions of His Highness and all Christian countries.”

After Britain and Oman had signed the Moresby Treaty in 1822, two British ships under the command of Captain William Fitzwilliam Wentworth Owen were dispatched to the Indian Ocean to survey the East African coast and Arabia.

The captain's mandate was to monitor and stamp out any slave trade activity in the region. Owen was a man so fervently committed to the cause of ridding the

world of slavery, that he sailed to Muscat on his ship, HMS Leven, to harangue Seyyid Said about the horrors of slave trade.

The other ship under his command, HMS Barracouda, paid a visit to Mombasa to stock up on supplies. The Barracouda sailed into Mombasa harbour on December 4th

1823.

The removal of his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar was pregnant with results for the East African littoral as the Sultan was enabled at once to escape from the weakening effects of the

internal dissension of Oman, while the geographical position of Zanzibar marked it out as a natural trade centre for the scattered settlements on the coast.

The activities of Sultan Said resulted in the establishment of his authority over the whole of what is now the coast of Kenya and Tanzania. The clove, the chief source of the prosperity of Zanzibar

today, was introduced by him into the island and trade increased, stimulated by the immigration to the coastal belt of Indians, who were not only traders but small capitalists who financed the Arabs

for journeys into the interior.

In 1862 the independence of Zanzibar was recognized by an agreement signed by both Great Britain and France but from this time forward the British influence at the court of Zanzibar, represented by Sir John Kirk who became Consul General in 1873, steadily established its ascendancy, so much so that in 1877 Sir William Mackinnon of the British India Steam Navigation Company, who had considerable interests in the East African littoral was asked by Sultan Barghash (successor to Sultan Majid and Sultan Said) to accept a lease for seventy years of the customs and administration of all the Sultan’s dominions, with certain reservations as to his own sovereign rights over the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba. The British Foreign Office, however; were not prepared to accord support and Sir W. Mackinnon was compelled to decline.

Yet, it is baffling that King Leopold in the Congo amassed a huge personal fortune by exploiting the natural resources of the Congo through brutal enslaving

and was obviously allowed to carry on without any intervention or by means of any type of humanitarian meeting as the Berlin Conference had done, that had started it all.

The initial task of the Berlin conference was to agree that the Congo River and Niger River mouths and basins would be considered neutral and open to trade.

Despite its neutrality, part of the Kongo Basin became a personal Kingdom (private property) for Belgium’s King Leopold II and under his rule, over half of the region’s population died or were they

killed? The Belgium king Leopold II turned a huge piece of Africa into his rural estate, enslaved its people, and left a legacy of misery that lasts until today.. The one difference is Leopold

killed black men , women and children in Africa and the Western narrative has always been soft on people of colour and their deaths.

Estimates of the death toll ranged to fifteen million, innocent men, women and children. Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909), Colonization 1876–1885, Congo Free State 1885–1908, Belgian

Congo 1908–1960… Read Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost for much more insight into this heinous crime and links the misery of the Congolese people of today to the horrors to which the

tyranny of King Leopold subjected Congo in the not too distant past.

In fact the estimate of the number killed during the transatlantic slave trade alone varies anywhere between 6-150 million. The official UN estimate is 17

million (UN). However, we ourselves would be

inclined to agree the figure of 60 million, given all the variables here, including the fact that during the entire period of the slave trade, Africa's population did not increase. Some may

argue that this is because Europe had advanced medicine and technology, while Africans didn't. Yet during this era Asia wasn't exactly at a sophisticated, technological level either. But their

population nearly doubled. We believe the stagnation of Africa's population is a by- product of the transatlantic slave trade. (World Future Fund).

European slave trading and abolitionism in the Indian Ocean also led to the development of an increasingly integrated movement of slave, convict, and

indentured labour during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and into the 20th century, the consequences of which resonated well into the twentieth century.

Global demographics in people of African descent/Origin as in similarities to the Americas, West Indies, Fiji, Madagascar, Re-Union, Mauritius, …etc are in

abundance to witness?

One can find the likes of JP Morgan and Lloyds of London …etc ”. The government certainly shelled out £20m (about £16bn today) in 1833. Not to free slaves but

to line the pockets of 46,000 British slave owners as “recompense” for losing their “property”. Having grown rich on the profits of an obscene trade, slave owners grew richer still from its ending.

That, scandalously, was what the taxpayer was paying for until 2015. Narrated by Kenan Malik of the Guardian

So what of other European Elite that benefitted and those that profited are all over the Western world as well as in Canada, USA, Australia, New Zealand South

America, West Indies….etc.

Right now you can look at millions of Brazilians, millions of African Americans, millions of African Caribbean; millions of broken communities in West Africa, millions of people in South Africa,

every single one of them the product of European systems that has not stopped to this very day.

Indentured labour from South Asia (1834-1917) a form of slavery…

The slave trade was officially abolished throughout the British Empire in 1807. Britain's darkest secrets: a form of

slavery ...After the abolition of slavery, newly free men and women refused to work for the low wages on offer on the sugar farms in British

colonies in the West Indies. Indentured

labour was a system of bonded

labour that was instituted following the abolition of slavery.

Indentured labour were recruited to work on sugar, cotton and tea plantations, and rail construction projects in British colonies in West Indies, Africa and South East Asia. From 1834 to the

end of the WWI, Britain had transported about 2 million Indian indentured workers to 19 colonies including Fiji, Mauritius, Ceylon, Trinidad, Guyana, Malaysia, Uganda, Kenya and South

Africa.

The gradual abolition of the slave trade and slavery in European colonies was the source of new migrations of labourers throughout the world, notably during

the second half of the nineteenth century. In order to meet the needs of a labour-intensive plantation economy or to build the central infrastructure of their colonies, the Europeans—for the most

part the English, French, Portuguese, and the Dutch—called on free foreign labourers.

This was known as the indenture system (which means “contract”), or the coolie trade if the indentured labourers were from Asia (coolie being derived from the Tamil word for salary).

These new flows of indentured manpower were dictated by the colonial expansion of Europe, as well as by the difficult socio-economic conditions in the countries where the indentured labourers came

from, which acted as a powerful factor for departure.

The workers, the majority of whom were men, were directly recruited by the colonial administration or by immigration agents. For example, Javanese, Japanese, Tonkinese, Africans, Madagascans and

especially Chinese and Indians left their native land to go and work, in exchange for a salary, in the colonies of the Americas and the Indian Ocean, or in the territory recently conquered by the

imperial powers in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Between 1834 and 1920, approximately 1,500,000 indentured labourers, of whom 85% were from India, were sent to British colonies, one third to

Mauritius, one third to the British West Indies, and the rest to Natal. Tens of thousands of Indian workers emigrated to the French colonies of La Réunion, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French

Guiana.

750,000 Chinese left for Malaysia, Sumatra, Cuba, the British West Indies, or La Réunion. This is not to mention the tens of thousands of African workers who went to the West Indies, French Guiana,

La Réunion, Mauritius or Natal. Those who went to the Indian Ocean came from Mozambique or Zanzibar, and those who went to the Atlantic region were from the Congo and Senegal. Experiments were also

made with European workers (Maltese, Irish, French), but without success.

1813/15: Although it is described as Gradual emancipation adopted in Argentina. An academic in the history of Slaves in Argentina narrated: How Argentina Killed

Millions of Her African Population To Become a Purely Caucasian Nation

"So although they abolished slavery in 1815 in Argentina, it continued until 1853, after that the main preoccupation of the leaders was how to get rid of the

black slaves and their descendants. Our president who ruled us from 1868 to 1874, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, wrote in his diary in 1848, this was long before he became president and slavery ended

that - 'In the United States… 4 million are black, and within 20 years will be 8 million…. What is to be done with such blacks, hated by the white race?' - It shows that he was already thinking of

how to eliminate black people before he became President and when he became President, he succeeded."

"Didn't the world say anything?"

"No. They ignored it. I am sure most of them wanted to do the same thing but failed. At that time, they admired them. I remember when I will go to Brazil as a

child, my father's friend will say in disgust as he looked at the black Brazilians - we should have had your guts and finished them off. All of them. Make Brazil white just like

Argentina."

1814: Gradual emancipation begins in Colombia. Slavery was practiced in Colombia from the beginning of the 16th century until its definitive abolition in 1851. This process consisted of trafficking in people of African and indigenous origin, first by the European colonizers from Spain and later by the commercial elites of the Republic of New Granada, the country that contained what is today Colombia. (Wiki)

1823 Slavery abolished in Chile. Chile abolished slavery in 1823. Article 19.2 of the Constitution expressly states that “There are no slaves in

Chile, and those who tread its soil shall be free”.

1824 Slavery abolished in Central America.

1829 Slavery abolished in Mexico.

1831 Slavery abolished in Bolivia.

1833 Abolition of Slavery Act passed in Britain. Slavery Abolition Act, (1833), in British history, act of Parliament that abolished slavery in most British

colonies, freeing more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa as well as a small number in Canada. It received Royal Assent on August 28, 1833, and took effect on August 1,

1834.

Britain ..The slave trade was actually abolished in

1807. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act abolished, as the name suggests, slavery itself. A Treasury so loose with its facts might explain something about the

state of the British economy. Worse, however, was the claim that British taxpayers helped “buy freedom for slaves”. The government certainly shelled out £20m (about £16bn today) in 1833. Not to free

slaves but to line the pockets of 46,000 British slave owners as “recompense” for losing their “property”. Having grown rich on the profits of an obscene trade, slave owners grew richer still from

its ending. That, scandalously, was what the taxpayer was paying for until 2015. Kenan Malik

1842 Slavery abolished in Uruguay.

1848 Slavery abolished in all French & Danish colonies.

Proclamation of the Abolition of Slavery

in the French Colonies, 27 April 1848, 1849, by François Auguste Biard, Palace of Versailles

1851 Slavery abolished in Ecuador.

1854 Slavery abolished in Peru and Venezuela.

1863 Emancipation Proclamation issued in the U.S.

1863 Slavery abolished in all Dutch colonies.

1865 Slavery abolished in the U.S. as a result of the end of the Civil War.

Britain was one of the most successful slave-trading countries. Together with Portugal, the two countries accounted for about 70% of all Africans transported

to the Americas. Britain was the most dominant between 1640 and 1807 and it is estimated that Britain transported 3.1 million Africans (of whom 2.7 million arrived) to the British colonies in the

Caribbean, North and South America and to other countries.

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/british-transatlantic-slave-trade-records/

Queen Isabella’s First Decision on Enslavement of Indians

The sequel to Encounters Unforeseen will depict Queen Isabella’s decisions from 1493–1498 with respect to the enslavement of each of four shipments of Native American captives that Columbus or his brother dispatched to Spain during this period.

https://www.andrewrowen.com/queen-isabellas-first-decision-on-enslavement-of-indians/

The story of East Africa’s role in the transatlantic slave trade

Foundation essay: This article is part of a series marking the launch of The Conversation in Africa. Our foundation essays are longer than usual and take a wider look at key issues.

The recent discovery of the remains of the Portuguese slave ship São

José off Cape Town has brought East Africa’s role in the transatlantic slave

trade to public attention. But the São José was merely one of a large number of slave vessels that either rounded the Cape or put into Table Bay for refreshment.

https://theconversation.com/the-story-of-east-africas-role-in-the-transatlantic-slave-trade-43194

Foundation essay: This article is part of a series marking the launch of The Conversation in Africa. Our foundation essays are longer than usual and take a wider look at key issues.

The story of East Africa slaves.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [498.5 KB]

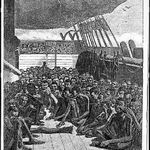

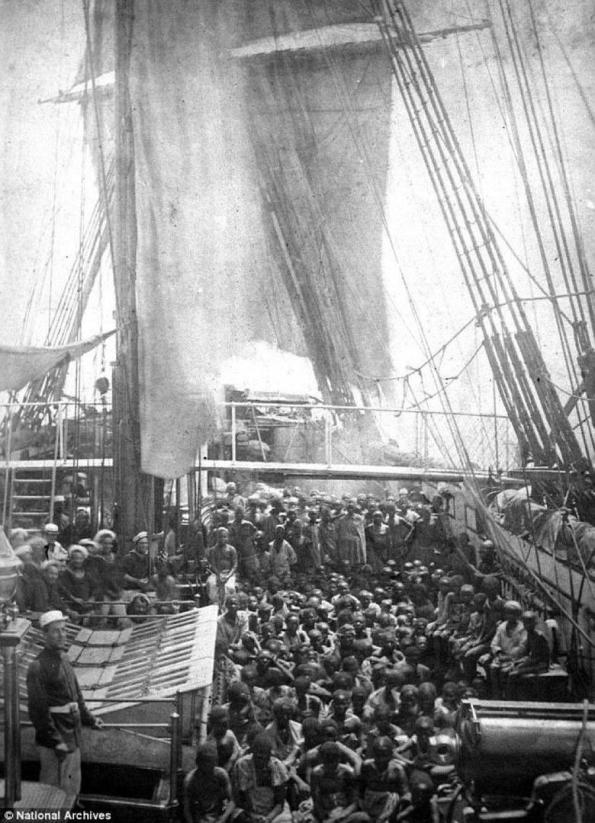

A photograph of a slave ship captured by the British Navy in 1868.

After the British naval blockade of West & Central Africa in 1808 - 1865, slave traders moved to East Africa to circumvent the blockade. Primarily to Mozambique, Zanzibar & Madagascar. This ship was captured off the coast of Zanzibar.

Click on photo below for more

Full text of "Anti-Slavery Reporter and Aborigines' Friend November-December 1906: Vol 26 Iss 5"

CONTENTS. ay THE SLAVE TRADE IN PORTUGUESE WEST AFRICA. ... and besides raiding the Chief used to.sell slaves to the Mombari (Portuguese slave-dealers), ...

CONTENTS...THE SLAVE TRADE IN PORTUGUESE EAST/CENTRAL AFRICA. ... and besides raiding the Chief used to.sell slaves to the Mombari (Portuguese slave-dealers),

Val Gielgud and the Slave Traders.docx

Microsoft Word document [4.1 MB]

Slavery & the Bank

Explore the Bank of England Museum exhibition ‘Slavery & the Bank of England’.

The exhibition traces the connections between the history of the Bank of England, the business of the City of London at large and transatlantic slavery.

You can find the exhibition in the Rotunda at the back of the museum. When you enter the space, take left to start the tour and look for audio guide symbols on the exhibition cases.

History of the Swahili East Coast of Africa ...click below

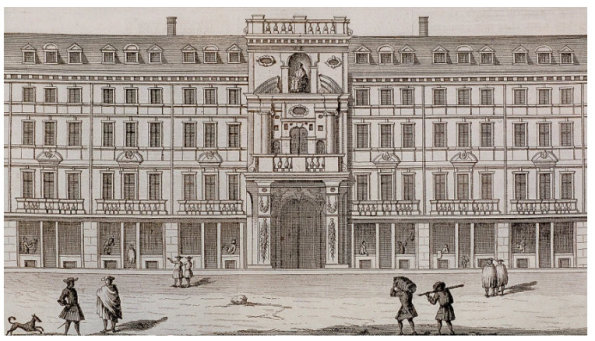

The East India House, Leadenhall Street, after the rebuilding of 1729

The Tragedy of French Colonialism... The Congo Ocean Railroad

We were unrelentingly made to believe that the Slave trade was over, through “The Slavery Abolition Act 1833” was repealed in its entirety by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1998. The

repeal has not made slavery legal again, with sections of the Slave Trade Act 1824, Slave Trade Act 1843 and Slave Trade Act 1873 continuing in force.

Slavery continued even after 1833 in many parts of the colonization overseas, this continued even through the heinous indenture labour (form of slave trade) in the 20th century.

Abolition Act abolished, as the name suggests, slavery itself. A Treasury so loose with its facts might explain something about the state of the British economy. Worse, however, was the claim that

British taxpayers helped “buy freedom for slaves”. The government certainly shelled out £20m (about £16bn today) in 1833. Not to free slaves but to line the pockets of 46,000 British slave owners as

“recompense” for losing their “property”. Having grown rich on the profits of an obscene trade, slave owners grew richer still from its ending. That, scandalously, was what the taxpayer was paying

for until 2015.

Going back to 1833 and after the 1880s some nearly half a century after, as the European powers were carving up Africa, one part of the story about King Leopold II of Belgium seized for

himself the vast and mostly unexplored territory surrounding the Congo River. Carrying out a genocidal plundering of the Congo, he looted its rubber, brutalized its people, and ultimately slashed its

population by ten million--all the while shrewdly cultivating his reputation as a great humanitarian.

Heroic efforts to expose these crimes eventually led to the first great human rights movement of the twentieth century, in which everyone from Mark Twain to the Archbishop of Canterbury

participated. King Leopold's Ghost is the haunting account of a megalomaniac of monstrous proportions, a man as cunning, charming, and cruel as any of the great Shakespearean villains. It

is also the deeply moving portrait of those who fought Leopold: a brave handful of missionaries, travellers, and young idealists who went to Africa for work or adventure and unexpectedly found

themselves witnesses to a holocaust.

Adam Hochschild brings this largely untold story alive with the wit and skill of a Barbara Tuchman. Like her, he knows that history often provides a far richer cast of characters than any novelist

could invent. Chief among them is Edmund Morel, a young British shipping agent who went on to lead the international crusade against Leopold. Another hero of this tale, the Irish patriot Roger

Casement, ended his life on a London gallows.

Two courageous black Americans, George Washington Williams and William Sheppard, risked much to bring evidence of the Congo atrocities to the outside world. Sailing into the middle of the story was a

young Congo River steamboat officer named Joseph Conrad. And looming above them all, the duplicitous billionaire King Leopold II. With great power and compassion, King Leopold's Ghost will

brand the tragedy of the Congo--too long forgotten--onto the conscience of the West.

Well, it did not stop here the people of the Congo thought King Leopold’s II misery had devastated their country through genocidal plundering of the Congo, he looted its rubber, brutalized its

people, and ultimately slashed its population by ten million plus and the West did nothing at all.

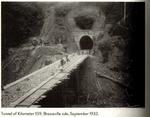

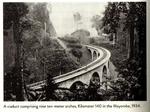

Enter France, the poor people of the Congo in the 1920’s had “ The Congo-Ocean railroad” that stretched across the Republic of Congo from Brazzaville to the Atlantic port of Pointe-Noir. It was

completed in 1934, when Equatorial Africa was a French colony, and it stands as one of the deadliest construction projects in history. Colonial workers were subjects of an ostensibly democratic

nation whose motto read “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” but liberal ideals were savaged by a cruelly indifferent administrative state.

Nearly entirely forgotten today outside central Africa, the Congo-Ocean was one of the deadliest construction projects in history. The railroad likely caused between 15,000 and 23,000

African deaths, according to investigations conducted in the 1930s. Unofficial estimates were far higher, ranging from 30,000 to 60,000. In truth, the exact number of men, women, and children who

died in the building of the Congo-Ocean can never be known. French government statistics were not kept until a few years into the construction, and even then they attempted to document only those

workers who died on the worksite.

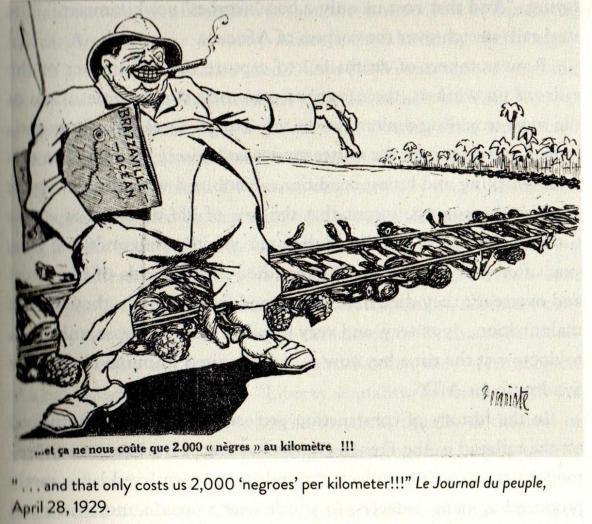

Well in the “Le Journal du people” dated April 28th 1929…. The French boast about this devastation feat that they had achieved, as quoted “ and that only costs us 2,000 “ negroes” per kilometre, 540 kilometres from the coast 70 kilometres east of Pointe-Noire through the Mayombe and onto Brazzaville!!!!

The Congo-Ocean railroad stretches across the Republic of Congo from Brazzaville to the Atlantic port of Pointe-Noir. It was completed in 1934, when Equatorial

Africa was a French colony, and it stands as one of the deadliest construction projects in history. Colonial workers were subjects of an ostensibly democratic nation whose motto read “Liberty,

Equality, Fraternity,” but liberal ideals were savaged by a cruelly indifferent administrative state.

African workers were forcibly conscripted and separated from their families, and subjected to hellish conditions as they hacked their way through dense

tropical foliage—a “forest of no joy”; excavated by hand thousands of tons of earth in order to lay down track; blasted their way through rock to construct tunnels; or risked their lives building

bridges over otherwise impassable rivers. In the process, they suffered disease, malnutrition, and rampant physical abuse, likely resulting in at least 20,000 deaths.

Ln the Forest of No Joy captures in vivid detail the experiences of the men, women, and children who toiled on the railroad, and forces a reassessment of the

moral relationship between modern industrialized empires and what could be called global humanitarian impulses—the desire to improve the lives of people outside of Europe. Drawing on exhaustive

research in French and Congolese archives, a chilling documentary record, and heart breaking photographic evidence, J. P. Daughton tells the epic story of the Congo-Ocean railroad, and in so reveals

the human costs and contradiction of modern empire.

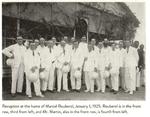

On New Year’s Day 1925, Marcel Rouberol, the chief representative

of the Societe de construction des Batignolles, one of the largest French engineering firms at the time, held a reception at his home near Pointe-Noire for the men who worked under him. It was one of

many gatherings that company employees organized to fight the boredom, homesickness, and sense of isolation that came with living and working on an inclement expanse of sand thousands of miles from

home.

From 1921 to 1934, men from “the Batignolles” lived near the coast in Middle Congo, often referred to by the French as simply’ “the Congo,” a region in the

southern part of French Equatorial Africa. They worked on building the Congo-Ocean railroad, a massive construction project that the colonial government under took in the years just after the First

World War.

Long heralded by Frenchmen as essential to the economic development of the region, the railroad would connect the city of Brazzaville, the colony’s largest settlement on the upper Congo River,

to Pointe-Noire, on the Atlantic coast, where the French planned to build a deepwater port. Covering only some 512 kilometers, fewer than 320 miles, the rail¬road was not terribly long. But it

crossed difficult terrain, especially the dreaded Mayombe, where the rails wound atop unstable, sandy soil, through a region of thick forests, mountains, and gorges.

A day like New Year’s was worthy of a photograph—eighteen white men, all in pressed white linen suits, each with his white pith helmet in his hand.

Corporations are built on hierarchies, so placement and positioning were essential in the picture, which was to be sent to company headquarters in Paris. The two men front and center are Rouberol and

M. Martin, the lead engineer on the construction site. Around them are engineers, administrators, and overseers of the project. Two African auxiliaries, perhaps assistants or secretaries, lacking

white linen and helmets, are wedged against the right edge of the image, one of them literally cut off by the frame, behind I heir white superiors.

The Batignolles men exuded confidence on that New Year’s Day, none more so than Rouberol himself: his trimmed beard, neat tie, and impeccably white shoes

complemented the self-assured smile on Ins face. Receptions like this one allowed these men and a handful of wives to come together and celebrate their accomplishments and discuss the work ahead.

Despite their distance from France, executives of the Batignolles recreated some of the comforts of home.

Boats from Europe brought in not only supplies to build the rail- load but regular shipments of garlic, onions, and potatoes; refrigerated cheeses and

charcuterie; jams and butter; rum, wine, and Moet champagne; Vichy and Perrier mineral water; coffee, Cointreau, and cigars. A New Year’s party was just the place to enjoy all that civilization

could offer.

Despite the inclement weather and prevalence of disease, the white men in the photograph, all well fed and standing tall, appeared to be paragons of

camaraderie, cleanliness, and health. The photo was a testament to France’s determination to triumph over the climate and landscape in a part of the world that Europeans considered insalubrious and

uncivilized. The men of the Batignolles, as well as champions of the railroad in France, heralded the Congo-Ocean as an engineering colossus achieved in the deadly wilds of the African continent. It

would, as one newspaper put it, “save” Equatorial Africa, regularly called the “Cinderella” of the French Empire, and open the region’s “nearly limitless” reservoir of riches.

While this portrait of colonial power is telling in many ways, i here is another story that it does not tell—and that it in fact hides— in its straightforward

simplicity. Just a short walk from the New Year’s celebration was the construction site of the Congo-Ocean where African men and women worked ten hours a day, six days a week, clearing millions of

cubic meters of earth, building bridges and tunnels, and laying the ties and rails of the train line. For the thirteen years of construction, the workers wore minimal clothes and lived communally in

huts so crowded and poorly ventilated that many chose to sleep outdoors.

They faced overseers, both European and African, who often verbally tormented and beat them. They survived on a starvation diet and often went days without eating. Fresh water was in short supply,

adding to the problem of dysentery that continually weakened the labor force, at certain points sickening or killing more than half the workers. Needless to say, French cuisine was never on the

menu.

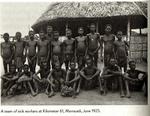

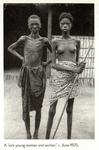

A second photograph, also taken in 1925 and not far from Rouberol’s home, brings the plight of these workers somewhat into focus. I In. image illustrates a

very different side of the railroad project. The emaciated frames of these two unnamed people, identified only as a “sick young woman and worker,” suggest they suffered from severe malnutrition and

perhaps dysentery or beriberi, a thiamine deficiency common among the poorly fed recruits. The cachexia, in extreme wasting, of their bodies is reminiscent more of famine victims or prisoners of war

than of what the French insisted they were- free, protected laborers in a republican empire.

Unlike the proud stances of the men of the Batignolles, these young people’s bodies and faces betrayed uncertainty, humiliation, fear and despair. It is

impossible to know what exactly the “sick young woman and worker” thought about their predicament; the men of Batignolles rarely documented the opinions of their workers in an effort to strip them of

their voices and deny them their stories.

It is tempting to believe these two images came from different worlds, but they did not. Sent by steamer to France, the two pictures were placed in a book of

photographs, not unlike an old family album, that the Batignolles kept in order to record the progress and history of the railway.

The photograph of the two workers, with its unflinching documentary style, is reminiscent of many images used by humanitarian organizations to draw attention to atrocity and misery. The image, with the two young people framed by their background in a way that highlights their expressions and thin bodies, bears many hallmarks of what has been called the “aestheticization of suffering.”

But the purpose, or at least use, of this photograph is as not to elicit sympathy or even pity. Instead, this collection of photos of workers, which were

regularly left out of the company’s publicly published material, filled out a private collection aimed at commemorating every aspect of the construction, from frustrations in daily habits to

triumphs.

Flipping through the Batignolles album reveals black and white photos of open plains, dense forests, rivers, and ravines; of laborers’ huts, tunnels, bridges,

a wharf, hand-pushed mine cars filled with dirt, and a newly built train station. There are photographs of the life of the construction for the Europeans, the white men and women carried by tipoye

(sedan chair), or pushed in a wheeled pousse-pousse by African servants, or gathered for a concert in a high- ceilinged hall, or greeting the governor-general of the colony on a visit. It can make

for jarring viewing.

On one page, two white men and two white women out hunting strike poses worthy of a Tarzan film, their African guides standing to the side, visually fading into the background. And a few pages

further on, a group of workers in the hot sun dig a massive trench without the help of machinery, pushing heavy wagonettes filled with dirt, under the watchful eye of European bosses. One, an image

of leisure and adventure among the colonial elite; the other, a portrait of coerced labor. A caption of the first photograph identified the white men and women by name; in the- second, the men

remained nameless in a scene labeled plainly " The Work at Kilometer 53.”

While such a juxta-position seems striking now, at the time Images of thin bodies, sick laborers, and men working in the equatorial heat were accepted parts of

the daily life of the Congo- Oceans.

Many Europeans on the construction site thought little of workers’ bodily conditions; indeed, most were convinced that Africans were better off for the

work. In 1925 Gabrielle Vassal, the English wife of the French director of public health in the colony, wrote in her memoir that, while the workers’ rations were “frugal, consisting chiefly of

manioc, it is at least regular, and in this starving country keeps them as a whole cheerful and healthy.” African malnutrition was a fact of life, she insisted, a by-product of inherent

values.

“The Congo population is always underfed,” Vassal continued with an insight shared by many fellow Europeans, “and it is impossible to sound the depths of their

laziness and want of thrift. They never even think of the very next day.” The Congo- Ocean—and all it represented about modern colonialism—would help rectify that.

Vassal’s opinions, like the Batignolles album, are remarkable less for what they say about colonial hierarchies and racism than for their consistent denial of

the full story of the construction of the Congo- Ocean railroad. Histories of colonialism, especially in Africa before the Second World War, are rife with examples of European assertions of

superiority in the face of allegedly savage subjects.

The triumph of “civilization” over recalcitrant “primitives”—often bluntly portrayed in the European press as white men in pith helmets over naked, dark-skinned villagers—is a principal trope of

modern imperialism. In this way, the Batignolles album was in keeping with European mentalities. What makes photos of champagne receptions juxtaposed with deprived workers particularly unsettling,

however, is the casual coupling of the quotidian and the perverse.

Recruitment to work on the Congo-Ocean was widely recognized, by Europeans and Africans alike, as a possible death sentence. As Andre Gide, the future Nobel laureate in literature, put it after a

visit to the French Congo in the mid-i92os, the Congo-Ocean was “a frightful consumer of human lives.”

Nearly entirely forgotten today outside central Africa, the Congo-Ocean was one of the deadliest construction projects in history. The railroad likely caused

between 15,000 and 23,000 African deaths, according to investigations conducted in the 1930s. Unofficial estimates were far higher, ranging from 30,000 to 60,000. In truth, the exact number of men,

women, and children who died in the building of the Congo-Ocean can never be known. French government statistics were not kept until a few years into the construction, and even then they attempted to

document only those workers who died on the worksite.

The many thousands who died during recruitment itself, or who fled from the construction site never to be seen again, were not counted as casualties, even though many never made it home. Considering

the serious administrative lapses evident during the construction from 1921 to 1934, even the statistics that do remain must be viewed with scepticism.

What is clear, however, is that the railroad was known, both in Equatorial Africa and in Europe, to be deadly. In France, its reputation gave rise to an

oft-repeated assertion that the builders of the Congo-Ocean laid as many corpses as railroad ties. In 1929 a biting cartoon from Le Journal du people showed a fat-cat capitalist, in white linen suit

and with cigar in mouth, presenting the Congo-Ocean, saying, “And that cost us only 2,000 ‘negroes’ per kilometer.” The steel rails stretch over the corpses of Africans.

Raw numbers of deaths fail to capture the full impact of the railroad on workers, their families, and their communities. One of the most troubling dimensions

of the Congo-Ocean was how prolonged and quotidian the mistreatment and misery became. The difficult working and living conditions, combined with thirteen years of sluggish progress, meant that the

loss of life unfolded at a torturously slow pace. Hundreds died per month; thousands per year, year after year after year.

Workers died at the hands of recruiters and overseers; they died in accidents and from wounds; they died of malnutrition dysentery, and very possibly, from a disease unknown to doctors at the time

but now called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS.

In the history of construction projects, the mortality witnessed on the railroad in the French Congo has few peers. Even many premodern construction projects

dependent upon enslaved labor rarely produced as many cadavers. In a little over a decade, more men and women died on the Congo-Ocean than in eighty years building the Pyramids of Giza.

In the modern era, railroad constructions around the world, including the building of thousands of miles of rails in the nineteenth-century American West, resulted in relatively few deaths compared

to the Congo-Ocean. Only the “French period” of building the Panama Canal in the 1880s witnessed comparable numbers of deaths—around 22,000—where workers fell to a repertoire of endemic diseases

including yellow fever, smallpox, and typhoid fever.

In terms of twentieth-century comparisons, the Congolese railway can be likened to the most notorious cases of construction- related violence found in

totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. While reliable figures are hard to come by, the sum of prison laborers who died in the early 1930s building the White Sea-Baltic Canal, or Belomorkanal, which

is often cited as one of the most brutal chapters of Stalinist rule, was likely lower than the number lost in Equatorial Africa.

Around twice as many Africans died building the Congo- as British, Australian, and Dutch POWs succumbed working on the Burma-Siam Railway during the Second World War. Known as the "death railroad,”

the horrors of the Burma-Siam were made famous by the book and film The Bridge on the River Kwai, as well as by memoirs of survivors. Of course, exponentially more Asians than white prisoners died on

that railroad, though their experiences have been far less often commemorated in books and film.

Key differences distinguish the case of the Congo-Ocean from other episodes of brutality or slavery. Most important, African workers were not prisoners of

Japanese militarism or Communist ideology. They were not slaves to pharaohs. Rather, they were subjects of a nation whose motto was “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” All the same, many thousands were

forced to work, usually at the end of a gun, a stick, or whip. They were shackled together, made to trek for weeks on foot through swamps, deserts, and forests, and packed on crowded

riverboats. Once on the site, they worked and lived in trying conditions where beatings were commonplace and payment, already meagre, was often withheld for no justifiable

reason.

Parallels to totalitarianism were not lost on men and women who had lived through the era of the Congo-Ocean. Rene Maran, the French 'Guyanese writer who was

the first person of color to win the prestigious Prix Goncourt, reflected after the Second World War that the “modern slavery” of the Congo-Ocean had been “worthy of the worst Hitlerian

practices.”

The immense colony, he noted, had been transformed into what would later be called “a concentration camp.” While comparison to the Shoah obscure the dynamics that allowed ostensibly liberal projects

like the Congo-Ocean to become sites of state-sponsored misery, Maran’s provocative comparison should encourage a deeper look at colonial violence, its causes, and its impact on the men, women, and

children who lived through it……. Narrated from page 1-11 in the book “In The Forest of No Joy”..by J.P Daughton an award winning historian….

Rwanda Burundi Genocide

Artice by United Africa

3l7at1m67gih12ce8d

·

RWANDA COMMEMORATES THE 1994 GENOCIDE AGAINST THE TUTSI ??

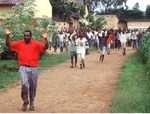

Today marks the 28'th commemoration of

the Rwandan Genocide against the Tutsi. The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi

minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were k.illed by armed militias known as the Interhamwe.

What you are looking at in this picture

are clothes carefully folded on benches. These clothes have been sitting on these benches since 1994 . These clothes belonged to the Tutsi people of Rwanda who were k.illed in the 1994 Rwanda

genocide. They were k.illed by rival tribes people, the Hutus.

Now, these clothes didn't get there by

accident. They are there because that exactly was where the owners of the clothes were when they were killed- in a church. They ran to the church because ideologically its suppose to be a place of

refuge. But the Hutus found them there, r.aped, b.asterdized & k.illed them there; men, women, children, old & young.

They were chopped like minced meat, majority of them were h.acked in the head with machetes. Their clothes are sitting on the church benches where they sat & laid, waiting for salvation as a

memorial till date. The genocide saw to the killing of approximately 1 million Tutsi lives.

Please click below....

#rwandagenocide1994.. https://www.facebook.com/hashtag/rwandagenocide1994

NEVER AGAIN!

History of Rwanda is like nowhere else that has ever happened in the 20th century amongst and within its own people, the Rwandan genocide is something that should

never ever be forgotten for many reasons and to now know/understand what and who gas lighted the region, as well who could have helped avoid this heinous crime.

In fact it was not based on religion nor culture, it was simply based on wealth, aggravated through colonialism awaiting a spark to ignite this beautiful small

region with the most heinous of crimes that brings, tears, shivers upon hearing the details to this genocidal in the making that could have easily been avoided.

Going back to the history of the region, Hutus arrived in the Great Lakes region of Central Africa a few thousand years ago; they were mostly farmers. About 400 years ago, the more nomadic Tutsis

arrived, and settled amongst the Hutus. Before long, however, economic differences arose. The Tutsis mostly herded cattle, while Hutus tilled soil. Cattle were more profitable, and over time the

minority Tutsis attained positions of power over the Hutus. Other than that, they were the same people.

It all started with the Germans, these Colonials invaded the region in around 1884, later on the Belgians took over after WW1 defeat of the Germans in 1917.

The two groups were separated further making them carry identity cards, and only permitted Tutsis access to higher education and positions of power. Classic divide-and-conquer move that has

always been the hallmark of the West and USA .

The region was split into two new nations in 1962 by Belgians during its Independence; there was struggle between both groups in trying to take control in Rwanda, Burundi and skirmishes flowing into

Uganda.

Majority significance of Hutus was taking shape in Rwanda and won power handily. Encounters and violence subsisted between Hutu and Tutsi in the region for the following three decades, but it was the

events of April 6th, 1994, that transformed into genocide.

Evidently a plane carrying Rwandan President who was a Rwandan politician and military officer who served as the second president of Rwanda, from 1973 until 1994. He was nicknamed Kinani, a Kinyarwanda word meaning "invincible". Plane also carried the

Hutu President of Burundi Cyprien Ntaryamira (6 March 1955 – 6 April 1994) was a Burundian politician who served as President of Burundi from 5 February 1994 until his death two months later. Violence had

been escalating in the three years leading up to this, with the Hutu government fighting Tutsi rebels called the Rwandan Patriotic Front. President Habyarimana agreed to a peace agreement with the

RPF, but then he got blown out of the sky, taking the peace along with it. It’s uncertain who shot down the aircraft, but what is not debated is who got the blame and what resulted.

Rwandan Hutu enraged saw this opportunity to carry out genocide against the Tutsi that they had been so longing for. This escalated the next day, makes one wonder how methodical it was structured in

an orderly and in an efficient manner and in a mere three months nearly a million Tutsis were slaughtered.

With Hutu forces focused on massacres, by mid-July the Tutsi-led RPF seized control of the government, and the revenge killing of approximately 100,000 Hutus followed. Canadian General Romeo

Dallaire, commander of a small UN observer force in Rwanda, saw the genocide coming months earlier and warned his superiors, but was told to stand down. The international community could have

intervened and saved hundreds of thousands, but instead did nothing.

Below are articles links that will help you further read into what was going on that has just

surfaced…..

Macron asks Rwanda to forgive France over 1994 genocide role

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-57270099

Israeli Arms Exports to Rwanda During 1994 Genocide to Stay Secret, Supreme Court Rules

Upholding decisions by a district court and the Defense Ministry, justices find that state security needs outweigh public

interest.

https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-arms-exports-to-rwanda-to-stay-secret-supreme-court-rules-1.5429999?fbclid=IwAR1EydFincxesmEBsmEL-_3-L4pijloR54TsxhTC4XJU5-TxccktAp8kf_c

America’s secret role in the Rwandan genocide

The violence that shocked the world in 1994 did not come from nowhere. While the CIA looked on, its allies in the Ugandan

government helped to spread terror and fuel ethnic hatred

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/sep/12/americas-secret-role-in-the-rwandan-genocide?CMP=fb_gu

Indentured labour plus much more...click below