The Magnificent Seven !!- Mombasa Cinema bosses 1960s-1980s!!

This photograph was taken on 12th August 1968...at some posh beach hotel in Mombasa...one month after KFC was created!!

- Kenya Film Corp (state owned film distributor) Managing Director Njoroge Mungai - in the center (wearing a sweater)

- Kenya Cinema - Raman bhai Samji Kala - 2nd left standing (in sunglasses)

- Naaz Cinema - Mitu Shah - front row 2nd left squatting

- Regal Cinema - Sultanali Hussein - first left standing, and Fatealli Hasham - third left standing

- Drive In Cinema - Mr Chiman bhai Patel (to the right of Njoroge Mungai - we see his face only; Mr Gordon bhai Patel (first right standing) (Cashier at the Drive In, Mombasa)

- Moons Cinema - Mahendra Shah - left of Njoroge Mungai (standing tall)

- Liberty Cinema - do you recognize the owner?

kneeling in the front row Shabbir Dodh (first left); Mohsin

Dodh (first right)

8. Majestic Cinema -Chuni Samji Kala ..squatting just in front of

Njoroge

does anyone recognize anyone else in the photo?

Contrary to some KFC was well received! everyone looks happy!!

By the mid 70's members of parliament in one particular parliament session were irritated with the lack of African participation!!...more on that later!!

Credit to Husseini Janmohamed and The Nation

Filmdom finds East Africa a happy hunting ground

Hollywood and British Film makers come to East Africa with many famous actors too, here is a fascinating coverage

on the Filming sets, the known characters that were globally a house hold name, tons of ice and the making of it that protected films, the locals that played a part in many ways in the making of many

successful movies….

HALLMARK OF ACHIEVEMENT IN THE BRITISH FILM industry is that of a production being chosen for the Royal Command performance. The United States rewards her best effort for the year with the Oscar. To films made in East Africa such distinctions have come in alternate years.

Choice for the 1951 Royal Command performance was Ealing Studios’ Kenya - made Where No Vultures Fly.

In 1952 Hollywood bestowed its highest award on “African Queen,” most of which was made in Uganda. What is the appeal and scope of East Africa as a filming centre which, when the finished product is offered, makes hard

hearted film pundits nod approvingly, sends box-office graphs sky-high?

According to one producer, working in Kenya in the early months of this year, it is only a passing phase. But

he was quick to qualify this by adding that it is a phase which will be repeated as generation succeeds generation.

The thirties broke new ground when Trader Horn, Africa Speaks and Sanders of the River showed the possibilities of “Darkest Africa” on celluloid as a paying proposition. But the real exploitation by the film camera came post-war.

Film executives were then in need of something new to act as a stopgap between the end of hostilities and the advent of the inevitable succession of “War” films. Eyes

were turned towards Africa. Its vastness and comparative unknown intrigued the film planners. Here were opportunities for outdoor filming on a lavish scale, vistas were immense, colours in a diversity of hues and brilliances were there to challenge the best that Technicolor, now firmly established, could portray.

First to move was Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who invaded Kenya in 1949. Their version of H. Rider Haggard’s ready -made classic, King Solomon's Mines, set the pattern. Its success was tremendous the world over. Here was something the public wanted.

Quick to see the possibilities, a British studio was next in the field. Unobtrusive in comparison with the glare of publicity that attended every M.G.M. move, Ealing Studios worked through late 1950 and early 1951 on a film that had as its theme the formation of Kenya’s National Parks.

Where No Vultures Fly .. fulfilled all the faith and driving conviction of its director and producer Harry Watt and Leslie Norman. The story was simple, but the shots of wild life and the setting, against the ever changing panorama of Kenya’s countryside, won the hearts of the millions who saw it.

John Schlesinger, head of the Schlesinger Organisation of South Africa, who co-operated with Ealing in making the film, described it as “the greatest animal picture ever.’’ Critics on both sides of the Atlantic, and in every other country where it was shown, echoed his verdict.The tempo of film visitors throughout the three territories then quickened.

Twentieth Century-Fox put Ernest Hemingway’s famous short story, The Snows of Kilimanjaro on the screen, with the towering grandeur of Africa’s most beautiful mountain dominating much of the action.

To Uganda went director John Huston and stars Katherine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart to make C. S. Forrester’s African Queen. Uganda was also the chosen site for White Witch Doctor, while, working on a restricted budget, a small independent British company was at the same time making Men Against the Sun, in which Kenya’s own film product, Zena Marshall, played.

So, through 1952, millions of feet of film were reeled off in capturing the East Africa scene, and at the close of that year there were no fewer than three units at work in the field at the same time.

M. G. M. had returned with an even bigger company than used to make King Solomon's Mines. This time refrigerators, lighting plants, and all “mod. con.” were to be found in the heart of the densest bush. Nothing savouring of personal privation was permitted to hold up production on John Ford’s Mogambo. In the army of technicians and extras needed to help Clark Gable and Ava Gardner portray life in the jungle were 100 Europeans, including 12 White Hunters. There were also 300 Africans.

In the middle of 1952, inspired by the success of Where No Vultures Fly, Ealing Studios sent Harry Watt wandering through East Africa in search of the right spot for a sequel. He found it along the Kenya coast—and West of Zanzibar started shooting in December.

Third filming party, and that most cut off from contact with civilisation, was the husband-and-wife team of Alfred and Elma Millotte who pushed through to out of the way spots of Kenya and Tanganyika photographing animal life for Walt Disney Productions.

In the past few years a new incentive has sent the film maker to Africa: the competition of television. He must now look for stories and settings, to which the television camera cannot span. This, and the fact that films of Africa are high on the list of popular appeal, account for the business now being done in East Africa. And filming business means good business for the countries in which a picture is being made. Besides the money the companies spend, they help the tourist industry with publicity.

Yet, paradoxically, Kenya’s climate and hours of sunshine, so often ranked among the best of the world, and boasted as among her major attractions, provides the biggest problem to film-makers. The glare from the sun can tax all the skill of a cameraman, forcing him to turn to filters of web-fine mosquito netting, to obtain the best results.

One cameraman who experienced such difficulties this year was Paul Beeson in charge of the camera team making West of Zanzibar. He was in the unit which made Where No Vultures Fly, but since then promotion had come his way, and this was his big film chance Besides rising sand devils from the white beaches of Malindi, and the haze shimmering on the seas around Zanzibar, Beeson had to contend with the effect of humidity on his film. Every roll of film was kept in ice. As soon as it had been exposed it was rushed back to its ice box for protection until being flown to Britain for processing.

Many tons of ice were bought locally by Ealing Studios for his job when they were working along the coast. When a second unit went to Uganda in March, to shoot bush background scenes, they took a small ice-making plant with them.

In personnel, Ealing travel light, augmenting their staff with trained men available from the country which they are working. To make “West of Zanzibar” they flew from London a unit numbering only 22, of whom one was a woman. For 30-year-old continuity girl, Jean Graham, like many others in the party, it was a return to the scene of a former triumph. Many were members of that compact little unit who worked for months around the base of Kilimanjaro and the rock-strewn floor of the Great Rift Valley making what they fondly call “ Vultures.”

But for Jean Graham East Africa will always have a special memory. It was while on her first visit that a friendship with an Ealing cameraman blossomed into romance. On her second visit she had become Mrs. Waterson—with husband, Chick, also a member of the unit.

Ted Searle, an Ealing construction manager, came back a second time. Work tie undertook on his first visit will remain long after Where No Vultures Fly and other films of East Africa are mere memories. With members of the staff of the Royal National Parks he constructed the studio’s base camp at Amboseli which was later taken over and enlarged by the Royal National Parks for their popular and successful game centre.

Three Nairobi film men, quick to return to location work with Ealing when West of Zanzibar was made, were Eric White, Bill Howell and Tony Dean. Eric White was an assistant director, responsible for much of the hiring and arranging of local crowd scenes, props and stand-ins

Bill Howell, a sound engineer who has worked with the greatest of names among film land’s directors, again took charge, as he had done in “ Vultures,” of the three-man unit within a unit, and the delicate battery-powered apparatus, used to put into a film the multitude of sounds which, as well as the spoken word, make up the sound-track . . . the sound of water breaking on a shore, the call of animals and birds, the background babble of Africans at work—all integral parts of the atmosphere of the story and its setting.

Tony Dean, for some years a leading member of the small but active film-making community in Nairobi, was location manager for West of Zanzibar. He seldom met members of the unit, for his was the responsibility of making arrangements and placing orders at the site on the itinerary one jump ahead of the place where the unit was currently filming.

While in Mombasa Tony Dean found himself faced with a problem common to the location manager and assistant director working in East Africa—the call for improvisation to replace the unavailable ready-made.

At one point in the story of West of Zanzibar a vital clue to the mystery of smuggled ivory is revealed by the breaking open of a tin of ghee dropped on an African porter carrying it to a dhow. Director Harry Watt thought tin debhis not in keeping with the character of the scene. He told Tony Dean he wanted something that “ smelt ” of an African port, a vessel that would appear bright and distinctive in Technicolor. The brick-red, shallow-necked mtungi was the obvious answer.

Tony searched Mombasa high and low but no mtungi-maker was to be found. With only days to go before the unit arrived he was getting desperate. Then one day he happened to glance from his car while in the Changamwe district, and glimpsed an ancient potter sitting astride his wheel, slowly fashioning bright red clay into vases, jars—and small-size mtungis.

Within minutes the old craftsman had an order for 150 mtungis. His mode of manufacture, unchanged through many centuries, was called upon to step up its rate of production to a pitch never previously dreamed of.

Another facet of the Ealing planning is the use made of local knowledge. While the Harry Watt unit was in Zanzibar they had the services of an Arab Magistrate, Mr. Jiddaw, as interpreter while they worked in scenes played on an Arab- manned dhow; for advice in all things dealing with dhows they had the assistance of the two executives of Southern Lines, whose small craft ply constantly around the shores of East Africa; for help in the hiring of Arabs, Asians and Africans for the crowd scenes in the Mombasa Old Harbour scenes, and for the placing of props of bales of cotton, bags of salt, stalks of bananas, they enlisted the aid and advice of the brothers Shariff Abdulrehman Shatry and Shariff Mohamed Shatry. The former is Mombasa’s dhow registrar, his brother is president of the Central Arab Association.

In contrast to some of the other film-makers, Mr. and Mrs. Millotte, working for Walt Disney, shun ballyhoo. It ruins their work. “We don’t even take an African with us on our safaris,’’ they explain." We must have perfect quiet to be able to photograph the animals in their natural state and acting naturally. The only way we can make certain of that is to go alone.”

With two trucks stocked with tinned food, water and a minimum of camp kit the couple have trekked off for a month at a time into the loneliest parts of Kenya and Tanganyika. At the time of going to press they had been working for eighteen months and counted on staying another six.

The result of their work will be a full-length feature, the first of a new Disney series tentatively called True Life Adventure. It will portray intimately animal life in East Africa, from elephants right down the scale of sizes. The painstaking, patient couple, who won “Oscars ” for their brilliant features Seal Island and Beaver Valley, plan even to include sequences on insects. “We are very anxious to photograph the termites,” said Mrs. Millotte during one provisioning spell in Nairobi. These hunters, who carry a rifle only as a last resort for self-protection, have nevertheless some remarkable shots to their credit. One over which Mr. Millotte is particularly pleased caught a lion in the act of muffing a kill.

After some months in the Tsavo National Park the Millottes knew its animal highways and byways as well as any of the game rangers; they certainly knew of many secluded animal haunts which the tourist never troubles to find. Mudando Rock in the park, they declare, should prove a top attraction for tourists. Perched upon it they have looked down on as many as 350 elephants bathing in the pool below, playing and staging mock battles.

Not only will the Millottes’ work, when it appears on the screen, prompt tourists to book passages to East Africa, but many who have lived in the territories for years will be given a new appreciation of the fascinating wild life that is there for the patient onlooker to see.

Films have been made successfully in East Africa in the past are being made at this moment, but what of the future?Warnings have been sounded by people highly placed on both sides of the camera in the industry that the market is being swamped, that the animal appeal, and the primitiveness that is still Africa, have almost been played out.

For a confident note, to squash such pessimistic talk, let the last word come from a man who should know—Les Norman, who has been in the film business for twenty-five years. He is now one of Ealing’s top producers. As editor, director and associate producer he has been associated with such successes as Overlanders, Frieda, Nicholas Nickleby, Ureka Stockade, A Run for Your Money and Where No Vultures Fly. He got his chance as a producer with two of the outstanding films to be made in British studios within the past two years—Mandy and The Cruel Sea.

He says: “ East Africa has a definite filming future. I think many good films are still to be made in the country, and that many good stories are to be found there. This is largely because of the natural colour of its countryside, because of the character of its people, and because of its varying and always fine backgrounds.”

Nostalgic Places, Memorable Films of Different Era.

Kenya Cinema

THE MOVIE SCENE IN KENYA

Moons Cinema

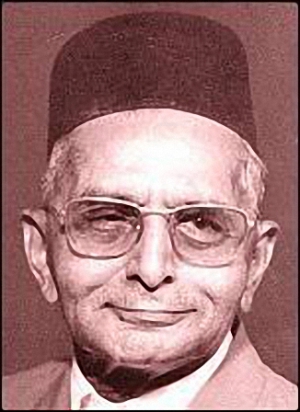

The Late Ameer Janmohamed with his wife Zeenat

If one reads a book called “A Regal Romance and Other Memories“by the late co-owner of Regal Cinema, Mr Ameer Janmohamed who came from a very prominent family in Kenya, he has clearly quoted saying, as follows:

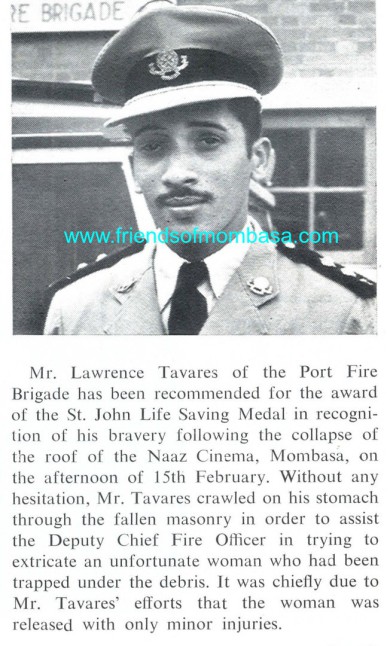

“The number was reduced later when two separate internal staircases serving the balcony had to be built to comply with new and more stringent fire regulations, following the collapse of the roof of the Naaz Cinema, which was built in 1951, twenty years after the Regal”.

Another quote “Built in 1930, the Regal Theatre Building went up in flames one night in September 1985. The fire started after mid-night, well after the last performance had finished; there was no loss of life or injuries. The very last film which had been shown that evening was an Indian movie called “Chandan ka Palna”. The Fire Department were of the opinion that somebody had left a lighted cigarette on an upholstered seat”.

Remembering Ameer Janmohamed’s Regal Cinema, Jeevraj Air Services, Fatehali Dhala

Nazz Cinema operator, the late Syed Mohamed Kassamali Shah

http://www.coastweek.com/obit/obit-20.htm

Late Kanwarlal Sabharwal Was

Accomplished Businessmen

In the 80's he bought out the 'Naaz' cinema, renamed it 'Lotus Cinema' and concentrated on showing a mix of 'Kung Fu' epics, westerns and religious films popular with old town audiences.

AWAAZ MAGAZINE

Naaz ki Kahaani Meri Zubani. (The story of Naaz and my testimony)

By Ramzan Allan

Up till the time that the Naaz Cinema finally rose up at this site in the early fifties, Messrs Samji Kala and their company Majestic Theatres ruled the roost. Other than the Regal Cinema which screened mostly English films, there was no competition and films lay canned in Samji Kala's warehouse at times for more than two years before being released. There were no DVDs or VHS or Internet at that time! Then the Moons [Cinema] loomed up on the horizon and the race was on!

OWNER OF MAJESTIC AND KENYA (QUEENS) CINEMA IN MOMBASA

Late Mohanlal Kala Savani of Samji Kala & Co. Ltd., Mombasa.

The pioneer Kenya businessman,passed away in 1998 at the age of 98 years. Having arrived at Mombasa just after the First World War (1918) he founded his business which through the years he expanded not only in Kenya but all over East Africa.

His concerns included import and export of raw cotton, textiles and various other items. He had established one of the leading film distribution and Cinema business throughout East Africa since 1930, and was a Founding Member of such industries as Kicomi, African Cotton Industries, Samex Textiles and Mombasa Towel Manufacturers. Furthermore, he was one of the leading property developers on the Kenya Coast.

Mohanbhai was a silent and constructive public working and elder guide to many and a very generous donor to many local charities. He was also a Trustee of the Mombasa Lohana Community during his lifetime. Narrated by Nalin Raichura

Memorable Films & Links

Memorable Films and Links to them.

http://www.moovyshoovy.com/hindi_movie_list.php?era=196

http://www.hindigeetmala.net/singer/

The story behind the Fox Drive-In Theatre

Historic Cinemas of East Africa