The Swahili Coast and Indian Ocean Trade

The Swahili community of modern Mombasa is composed of an amalgam of the descendants of the early 'Shirazi' settlers and more recent Swahili groups, most of which migrated south to Mombasa Island during or after the 16th century. In 1591-93 the 'Shirazi' polity was destroyed by the Portuguese and their local allies. Hereafter Mombasa's accretions of foreign Swahili gradually reorganized themselves into 12 mataifa ('tribes'), divided among two confederations, the Thelatha Taifa (The Three) and the Tisa Taifa (The Nine). The gap between the two confederations was bridged by means of a loosely structured state system under foreign dynasties of Omani Arabs, first the Mazrui (appr. 1735-1837) and later the Busaidi (1837-95). During the Mazrui Mombasa was an independent city-state with hegemony over much of the Kenya and north Tanzania coasts. Under the Busaidi the city was incorporated in the Zanzibar Sultanate. The diffirences between the Three and the Nine faded during the Busaidi period and have almost disappeared since 1900. Notes, figures, summary.

https://www.africabib.org/rec.php?RID=18959313X

The Journal of African History

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history

The Swahili Culture - 0 to 1500 CE - African History Documentary

The original inhabitants of the Swahili Coast were Bantu-speaking Africans, who had migrated east from the continent's interior. They eventually spread up and down the coast, trading with each other, with the people of the interior, and eventually people from other continents.

Swahili coast cultures are diverse African cultures,

made up of a confluence of peoples. They are traders and farmers, cattle keepers, & fisher people who

have moved and interacted across land and sea for centuries (see chronology table below), and importantly, before the rise of Islam in the late 8th century. Trade is not the only story to tell about

the region.

- Swahili means “people of the coast” in Arabic. The coast and its links with external cultures has been overemphasized at the expense of the role of inland populations. For a long time, racist perspectives believed that the uniqueness and cosmopolitan aspects of the Swahili were because the Swahili were Arab immigrants. New scholarship understands the Swahili as home to African populations and similarities between inland and coastal sites show that they were part of the same society.

- A long history of trade of various luxury goods as well as enslaved peoples set the region at the center of global intercontinental networks, linking the Swahili coast to the Arabian peninsula, China, India, and Cambodia, among other places. In the 15th century, Europe – via the Portuguese intrusion and later the Dutch and British – entered this matrix as pirates and as authoritarians seeking trade monopoly because Europe had nothing of great value to trade.

- Trade allowed for rich cultural exchange that is evidenced in food, dress, architecture, language, and religion. The KiSwahili language is an archive that offers a rich entry point into study of the region, as it is a Bantu- (African) language to which other words in Arabic and other languages were added .

- The key characteristic features of the coastal settlements (e.g. building with coral rock from the Red Sea) developed around the 11th century. Archaeological evidence shows a more active interaction with the maritime world at that time.

- Many coastal Africans began identifying as Swahili in the 19th and 20th centuries, in the contexts of

slavery and imperialism. When discussing past groups, referring to Swahili (in the sense of ethnic identity) to past populations is anachronistic. This is a valuable lesson for students about

the construction and fluidity of Swahili identity.

https://www.bu.edu/africa/outreach/teachingresources/history/ancient-to-medieval-history/indian/

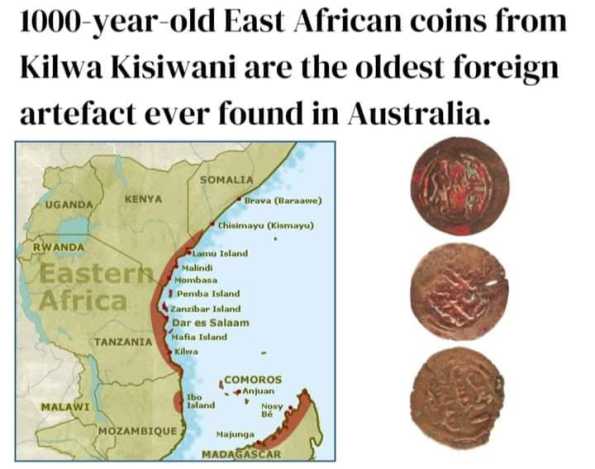

Unravelling the mystery of Arnhem Land’s ancient African

coins

1000-year-old African coins found in Australia.

The five ancient coins, believed to have been minted in present-day Tanzania, date back to the 8th to 15th century AD. They were made of copper, silver, and gold

and are thought to have been used as trade currency. The discovery of these coins on the remote and isolated Wessel Islands off the coast of Northern Territory in Australia has led to speculation

that ancient East African traders may have reached the continent long before the arrival of Europeans.

The Kilwa Kisiwani with its ancient capital city located on the coast of present-day Tanzania in East Africa, was a powerful empire that controlled the trade of gold, ivory and other valuable goods

from the African interior to the Indian Ocean.

The exact explanation for the presence of these coins remains a mystery, and further research and studies are needed to confirm their origin.

How did the five coins from distant Kilwa wind up in the isolated Wessel Islands? Was a shipwreck involved? Could it be that the Portuguese, who had looted Kilwa in 1505, reached the Australian

shores with coins from East Africa in their possession? Or was it that Kilwan sailors, renowned as expert navigators all across the sea route between China and Africa, reached Australia? Did they

trade with the Indigenous population? Or docked and left? Maybe some stayed.

The Red Sea to East Africa and the Arabian Sea: 1328 – 1330

The Sultan of Kilwa was called 'the generous' "on account of the multitude of his gifts and acts of generosity. He used to engage frequently in expeditions to the land of the Zinj people

[villagers of the interior], raiding them and taking booty [slaves and other wealth]... He is a man of great humility; he sits with poor brethren, eats with them, and greatly respects men of religion

and noble descent." [Gibb, vol. II, pp. 380 - 381]

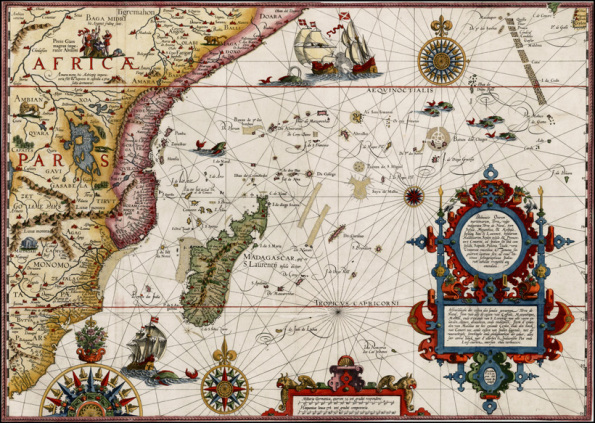

Indian Ocean Trade Routes

https://www.thoughtco.com/indian-ocean-trade-routes-195514

http://www.friendsofmombasa.com/mombasa-malindi-lamu/

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Kilwa, an island located off the coast of East Africa in modern-day southern Tanzania, was the most southern of the major Swahili Coast trading cities that dominated goods coming into and out of Africa from and to Arabia, Persia, and India. Kilwa flourished as an independent city-state from the 12th to 15th century CE largely thanks to the great quantity of gold coming from the kingdom of Great Zimbabwe to Kilwa's southern outpost of Sofala. Kilwa boasted a huge palace complex, a large mosque, and many fine stone buildings at its peak in the 14th century CE. The arrival of the Portuguese in the early 16th century CE spelt the beginning of the end of Kilwa's independence as trade declined and merchants moved elsewhere.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Kilwa/

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Often overlooked by visitors to East Africa, the coastal areas of southern Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania and northern

Mozambique boast several ruined and extant historical towns of significant cultural importance. Although some receive an increasing number of visitors - especially Stone Town in Zanzibar and Lamu in

Kenya - most sites seldom see a single soul. Places like Kilwa Kivinje and Pemba in Tanzania are notable for their remote and isolated location, whilst the city of Mogadishu has been a no go area for

years due to the ongoing Somali civil war. With his brief introduction to East Africas Shirazi and Omani mosques,

forts and residences, Werner Hermans intends to make a broader public familiar with the presence of world class, African monuments in a part of the continent for which it's early history is commonly

only associated with colonial influence.

https://www.wernerhermans.com/publication/Ancient-Arab-settlements-of-the-Swahili-coast

EAST AFRICAN CITY STATES

(1000-1500)

https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/east-african-city-states/

More links on Coastal History of Africa

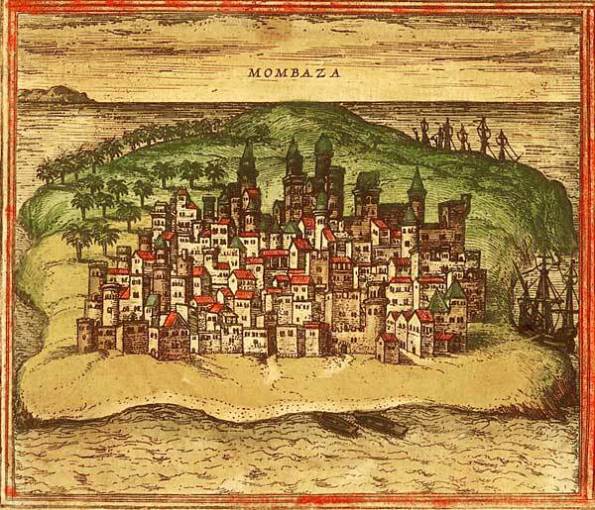

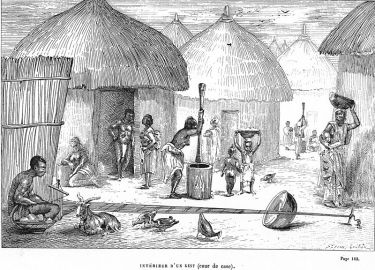

A Portuguese drawing of Mombasa in 1572, 17 years before it was sacked for the third time.

Mombasa 1505 — how Europe began the great plunder of Africa

Mary Oredi is a researcher at Kenyatta University, Nairobi,

Kenya

Kenyan socialist Mary Oredi and Charlie Kimber look back at a crucial moment in African history, when Portuguese forces attacked the African city of Mombasa.

Five hundred years ago an act of force and terror

symbolised a key turning point for all of Africa’s people. Portuguese adventurers sacked the city of Mombasa in what is now Kenya, slaughtering many of its inhabitants and destroying great cultural

treasures.

The butchery announced that European rulers were beginning a new phase in their relationship

with Africa. It was a grim forerunner for the five centuries of domination and cruelty that followed.

The regions the Portuguese assaulted were places of high culture and development. The

earliest description of the east coast of Africa was written in the second century AD. It comes from a sailor’s guide, probably compiled in Alexandria, in modern Egypt. Called the Periplus of the

Erythraean Sea, it demonstrates that routes along the coast of East Africa were, at the time of writing, well sailed and important for trade.

The document shows respect for East Africans. It talks of the land of Azania (Africa) where

“there is much ivory and tortoiseshell. Men of the greatest stature inhabit the whole coast and at each place have set up chiefs.”

From the earliest times East Africa began to make links with the rest of the continent and

with the Middle East. Arab migration brought Islam to East Africa.

Its spread, from about 700 AD, was mainly a peaceful process of gradual conversion. A society grew up that was both African and Arab.

Hostages

Long after he had

travelled through East Africa in 1331, the Moroccan scholar Ibn Batuta could still remember the town of Kilwa as “one of the most beautiful and best constructed towns in the world” — and by that time

he had seen the cities of India, China and his own Moorish countries.

Trade grew with China, symbolised by the arrival of a giraffe in Beijing as a present for the emperor in 1415.

Then the Europeans

arrived in East Africa. The Portuguese sailor Vasco da Gama is still often described as “the discoverer of the sea route to the East Indies”. In fact his skill lay in “discovering” knowledge held by

others.

Da Gama first arrived

on the east coast of Africa in 1498 and began looking for a route to India. When the Europeans and the Africans met, the Portuguese were impoverished in comparison with the well-dressed African

merchants.

Historian John Reader

writes, “When the fleet anchored in Mocambique a sheikh sent a sheep and great quantities of oranges, lemons and sugar cane to the ships. In return he was presented with a string of coral beads. This

was a gross insult, akin to offering a lump of coal to the owner of a coal mine.”

Da Gama’s followers

turned to force. They bombarded the town of Mocambique with cannon and took two Arab hostages.

To extract

information from the Arabs, the Portuguese dropped boiling oil on to their skin.

Sailing on, da Gama

was fortunate to find and hire the most famous Arab pilot of his age, Ahmad Ibn-Madjid. It was Ibn-Madjid who took da Gama’s fleet to Calcutta, India. Da Gama then returned to Africa where, with his

crews almost on the verge of extinction through scurvy, he was saved by the kindness of Africans.

Once re-equipped, the Portuguese returned home.

Murderous force

But now they knew the

riches that existed in East Africa, they resolved to return with a far more murderous force. The Portuguese attempted to justify their plunder by reference to religious

morality.

Much of East Africa

was Muslim, so Christian rulers said there was a duty to win it back. Pope Nicholas V, who had already blessed the Portuguese assault on Africa, confirmed that it was justified to enslave

non-believers. Such an ideology led to many atrocities.

When they arrived at

a city in their heavily armed vessels, the conquering forces would demand that the rulers accept Portuguese control and pay huge annual tributes. Cities that refused were attacked, burned and much of

their populations killed.

The Portuguese

attacked Zanzibar first. In 1503 the sea captain Ruy Luourenco Ravasco, working on his own initiative, blasted at the townspeople with his ship’s cannon until the sultan of Zanzibar agreed to pay an

annual tribute. For the rest of that year Ravasco and his companions sailed up and down the coast, seizing ships and ransoming them for payment in gold.

This was followed by

the officially organised assault. Francisco d’Almeida was sent with a fleet of 11 ships to seize control of the more important towns and cities.

The sultan of Mombasa

refused to pay tribute to the Portuguese and continued to maintain direct trading contacts with Arabia and the Persian Gulf.

Because of this

defiance, the city was partially destroyed in 1505 and then was subject to two further sackings in 1528 and 1589. After the third attack the Portuguese built a huge fortress at Mombasa which they

called Fort Jesus.

Completed in 1599,

Fort Jesus became the main centre of Portuguese authority in Eastern Africa for the next century.

Its massive, threatening walls symbolised the violence with which Portuguese domination of the trade along the East African coast was maintained for much of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Barbarities

The Portuguese attacks of the 16th century were typical of embryonic forms of market societies, pointing towards capitalism.

Africa was not yet

drawn into a world system of competitive imperialist accumulation, but the Portuguese raids were early examples of outside powers seeking to dominate whole societies — just as Columbus had done in

the Americas.

The terrible events

of 1505 were almost nothing compared to the barbarities of the Atlantic slave trade and colonialism which would come later as capitalism grew stronger.

But 1505 demonstrated

an attitude which opened the way to much worse. It should not be forgotten that around a third of the 12 million Africans who were transported from Africa between 1500 and 1800 were taken to sugar

plantations in Brazil by the Portuguese.

Those of us who have suffered the pains of colonialism, and still suffer from the way that the powerful dominate the globe, can see that 1505 was a terrible and crucial year.

https://socialistworker.co.uk/art/6088/Mombasa+1505+++how+Europe+began+the+great+plunder+of+Africa?fbclid=IwAR1AVCghZVTPKyv2-95VScpeaiqdIFzOLOSyStfEDBFuSj6TVEGvcdt9dLc

MAN-BASA CHRONICLES; Kuingia rahisi kutoka ngumu....

Stories abound on the ease of entering

Mombasa and the unease of getting out. The stories started eons gone by with the occupation of what was called Kongo-wea, Circa 900 AD.

Wa Kongo-wea were people from the African interior in a region associated with Congo by virtue of carrying the prefix 'Kongo' in many of the written texts dating back to the tenth century

AD.

Wa Kongo-wea were Abantu from the

interior also associated with a Bantu Queen called Mwana Mkisii who was the Matriarch of a community comprised of twelve families.

When the Arabs arrived around the 12th century, they found a thriving city state of 12 families they identified as Thenashara Taifa; Thenashara being the Arabic name for 12... also used to describe

the 12th hour of the day. Therein lays the link between the Coastal and the inland Abantu. Compared to the Nilotes who were principaly led by the Maasai, the Abantu of the time were led by the

Wakisii with tentacles all the way to the coast.

Wa-kongowea were peacefully settled in

an Island perfectly secured from the sorounding lands and teaming with Coconut palms for their winery and ready to consume mangoes that gave birth to the other name, Maembe tayari. The 15 square km

Island provided all their needs in a tranquil environment that was unmatched anywhere else along the East African Coast.

The initial Arab visitors were traders

who were welcomed with open arms for the exotic goodies they brought with them. As they came in peace, they were given a place to put up their settlement as they built trade links with the interior.

The ensuing bromance with Wa Kongo-wea gave birth to the very first Intermarriages that produced the Waswahili.

Thereafter, the Swahili hegemony spread out along the entire coastline. Uswahili therefore had its origins in Mombasa.

The other offshoot of the trade and

Intermarriage with the Arabs was the spread of Islam. The earliest stone Mosque on the Island called Mnarani dates back to 1300 AD.

For its deep shore and an harbor well

protected from the open sea, Kongo-wea became a famous trading port and a stopover for Trading ships from the city states of Sofala, Kilwa, Zanzibar, Malindi and Lamu. Sofala in particular was a

major Gold and Iron Ore transit town serving the rich mines of Zimbabwe Kingdom as it supplied its wares to Egypt, Mecca, India and China.

With time, Kongo-wea attained the

infamy of the beautiful girl pursued by many suitors. In its chequered history until the takeover by the British in 1824, Kongo-wea became a battlefield by Turks, Persians, Yemeni Arabs and the

Portuguese of course. Because of this, the locals changed its name to Mvita, the place of Wars.

The Arabs translated this to MAN-BASA. With time, the name became Mambasa and finally Mombasa possibly through the Portuguese lingua franca as they are the ones who wrote its history in the 16th

century.

Fort Jesus was built by the Portuguese in 1594 to serve as their Capital of the East African Coast as they serviced their trade routes to India.

The legendary Mombasa spiel of 'kuingia

rahisi kutoka ngumu' was born out of the physics of its geography.

Mvita was a perfect Island where the shortest distance to the mainland was 300 meters across a deep waterway. To Africans who

were obviously not sea-farers, crossing into the Island meant that one was at the mercy of the boat owners who were either the Portuguese, Arabs or the British colonists later

on.

For reasons of either language or

unbridled racism, the Portuguese had an interesting method of communicating with the locals even as they engaged in basic batter trading exchange. A gong was strategically mounted at the entrance to

the Fort where Africans bringing in items of trade would place them at the entrance and bang the gong once then retreat out of sight.

After ensuring that the African was out of sight through a peep-hole on the gate, the Portuguese would come out and place his wares beside what was on offer. He would then sound the gong twice and

disappear behind his fortified abode.

The African would them reappear and if he agreed with what was on offer, he would sound the gong once, collect his newly aquired goods and go away. In case he disagreed with the offer, he would sound

the gong twice, disappear and await a counter offer by the Portuguese.

This form of silent trade with the Portuguese gave birth to the term 'Mukuna Ruku'. The word is used by the

Meru, Akamba and Agikuyu to depict a feared leader or a respected person of means. The trouble the Portuguese took to keep away from their African counterparts is the reason they never shared their

drops to leave a genetic footprint on the East African Coast.

The very latest demystification of

Manbasa is the 1.2 km floating bridge constructed across the isles where once roamed the Mtongwe ferry. In his indefatigable service to the people, Uhuru Kenyatta commissioned the Liwatoni-Likoni

bridge that was put up in a record six months and was opened to the public in the last quarter of 2021.

For those politicos who believe Roads

and bridges are not food for the hungry, they may refer to the history of Mvita when the only way out was in a Master's ferry or an Arab dhow to slavery.

Manbasa: Kuingia ni rahisi, ata kutoka Sasa ni rahisi...Kiruki Mwithimbu

FACEBOOK...Swahili Coast Culture

Welcome to the home of Swahili Coast Culture - a boutique cultural enterprise.

Swahili Cosmopolitanism in Africa and the Indian Ocean World, A.D. 600–1500

Adria La Violette,

Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia, P.O. Box 400120, Charlottesville, VA

22904-4120, USAE-mail: laviolette@virginia.edu

ABSTRACT

________________________________________________________________

Coastal peoples who lived along the Eastern African seaboard in the first millennium A.D. onwards began converting to Islam in the mid-eighth century. Clearly rooted in and linked throughout to an indigenous regional Iron Age tradition, they created a marked difference between them-selves and their regional neighbours through their active engagement with Islam and the expanding Indian Ocean world system. In this paper I explore three ways in which interrelated cultural norms—an aesthetic featuring imported ceramics, foods, and other items, Islamic practice, and a favouring of urban living—created and maintained this difference over many centuries. These qualities of their identity helped anchor those who became Swahili peoples as participants in the Indian Ocean system. Such characteristics also can be seen to have contributed to Swahili attractiveness as a place for ongoing small-scale settlement of Indian Ocean peoples on the African coast, and eventually, as a target for nineteenth-century Arab colonizers from the Persian Gulf. This paper examines the archaeology of these aspects of Swahili culture from its early centuries through ca. A.D. 1500.

Ancient Arab settlements of the Swahili coast

An introduction to East Africa’s Shirazi and Omani monuments

Ancient Arab settlements of the Swahili [...]

Adobe Acrobat document [1.6 MB]

Click Below for more on Coastal history

Professor Ali Mazrui: Tools of Exploitation In Africa

When Black Men Ruled the World