The Native Peoples of the East Coast…by L.W Hollingsworth

The Native Peoples of the East Coast…by L.W Hollingsworth

We must now turn our attention to the native peoples of the coast region. The natives who now live along the coast were not the original inhabitants. Countless ages ago the greater part of

Africa near the Equator was inhabited by entirely different people from those of the present day. It is thought that these earliest inhabitants were a dwarf-like people. The only natives left at the

present day who resemble these aborigines are supposed to be the Bushmen of the Kalahari desert, the pygmies of the Semliki forest and Ruanda, the Wata who live among the Gallas, and the Tomal, Yehir

and Midgans who live among the Somalis.

https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/19170/SO)

It is said that the first negro people entered Africa many thousands of years ago from southern Asia. These people were black-skinned, woolly- haired, and had broad, flat noses. They

introduced into Africa the banana and various edible roots such as the Colacasia which grows in profusion in the rivers of Zanzibar island. These men were the ancestors of the negroes now living in

the Sudan. At a later period there came into Africa from a more north-westerly part of Asia a people of Hamitic race.

They introduced the goat and the dog into Africa, and also various grains. These Hamitic peoples intermarried with the negroes and thus produced a race generally called the early Bantu. The

Wanyamwezi, Wahehe, Washambaa and Wazaramo of Tanganyika Territory are representatives of these early Bantus.

Still later, probably 5,000 or 7,000 years ago, another kind of Hamitic people called the lighter Hamites, came into the continent either by Suez or the narrow Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb. The

ancient Egyptians were the best known representatives of the lighter Hamites. Some of these men mingled with the earlier peoples, thus forming what are known as the younger Bantu. The Chaga tribes

who inhabit Kilimanjaro and the Kikuyu of Kenya Colony belong to these younger Bantu. It will be seen, therefore, that the race of Bantu are not quite the same as pure negroes. The latter people live

in West Africa south of the Sahara desert. The Bantus are the result of a mixture of these negro peoples with various types of Hamitic peoples. With the exception of the Bushmen and Hottentots of

South Africa, and the Masai, Nandi and kindred tribes of East Africa, nearly all the present-day natives of Africa who live south of Latitude 5° N. may be called Bantus.

How then do we distinguish between the Bantu and the pure negroes of West Africa? We can do so by studying their languages. There are several hundred Bantu languages, but they are all

closely related and belong to one great family. On the other hand, the pure negroes speak languages which are quite different and distinct, so that even neighbouring tribes in West Africa are unable

to understand one another. Now, although one Bantu tribe speaks a different language from another Bantu tribe, yet there are certain resemblances between all the Bantu languages which would enable a

Bantu to learn another Bantu language much more easily than he would be able to learn a pure negro language. Thus a Mwanyamwezi would be able to pick up the Zulu language much more readily than one

of the West African languages, because both the Mwanyamwezi and the Zulu belong to the Bantu race.

We shall more easily understand the fact that all the Bantu languages belong to one family, if we examine several examples. Let us consider the word “Man” in one or two Bantu languages. In

Zulu it is “Umu-ntu”; in Xosa it is “Um-tu”; in Luganda it is “Omun-tu”; while in Swahili it is “M-tu.” You will readily perceive the similarity which exists between these various forms of the word

“Man.” Now let us look at the plurals. In Zulu the plural form “Men” is “Aba-ntu”; in Xosa it is “Aba-ntu”; in Luganda it is “Aba-ntu”; while in Swahili it is “Watu.” Here you will notice that the

grammar is similar in all four lan¬guages, for the plural of the noun is formed, in each case, by changing the prefix. One of the most striking features of all these Bantu languages is, in fact, this

use of prefixes and also of suffixes. The prefix or the suffix is added to the root of the word. Thus in the above examples the root of all the forms is “Tu,” and the plural is formed by altering the

prefix in front of this root.

The grammar of all the Bantu languages is mainly based on the correct use of prefixes and suffixes, for adjectives, pronouns, and verbs change according to the noun with which they are

related. Several examples from Swahili will perhaps make this clearer. A “good man” is “M-tu m-zuri,” while a “good book” is “ki-tabu ki-zuri.” In the above example it will be seen how the prefix of

the adjec¬tive “zuri” changes in order to agree with its noun.

Let us look at another example. The sentence “Two men have arrived” is in Swahili, “Wa-tu wa-wili wa-mefika,” whereas the sentence, “Two canoes have arrived” is “Mi-tumbwi mi-wili i-

mefika.” Here it will be noticed that both the adjective and the verb change in relation to the noun.

Another common feature of all the Bantu languages is that almost all the words end in vowels. If you think of a number of Swahili words, you will at once realize the truth of this

statement.

We have spent some time in considering the meaning of the word Bantu, because the native peoples of the East Coast, most of whom are Swahili, belong to this race. The literal meaning of the word Swahili is “Coast People,” for it comes from an Arabic word “Sahil” which means “Coast.” The Swahilis are a Bantu people with a certain amount of Arab blood. We have already seen how, from very early times, visitors from Arabia have come to these parts. Many of these Arabs intermarried with the Bantu peoples living along the coast, thus forming the people usually known as Swahilis. In the same way, Swahili, although a Bantu language, contains a very large number of Arabic words.

CUSHITIC AND NILOTIC PREHISTORY:

CUSHITIC AND NILOTIC PREHISTORY:

NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FROM NORTH-WEST KENYA

Recent archaeological research conducted west of Lake Turkana, Kenya has shed new light on the prehistory of eastern Cushitic and Nilotic speakers in East Africa. The Namoratunga cemetery and rock art sites, dated to about 300 B.C., are clearly related to the prehistory of Eastern Cushitic speakers. The newly defined Turkwell cultural tradition, dated to the first millennium A.D., is associated with eastern Nilotic prehistory. Lopoy, a large lakeside fishing and pastoralist settlement, is discussed in terms of eastern Nilotic prehistory. The archaeological data agrees with the independent findings of historical linguistics.

BY

B. M. LYNCH AND L. H. ROBBINS

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Elongated African theory is an evolutionary hypothesis devised by the late Belgian anthropologist Jean Hiernaux. It was introduced in his 1974 book

The People of Africa, a work which seeks to explain the existing physical and genetic diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa through various developmental processes. Touting itself as using a then new non-racial approach, the narrative places an emphasis on environmental adaptation as one of the primary driving forces behind human biological variation.

https://landofpunt.wordpress.com/tag/khoisan/

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

More on MALINDI

Malte Brun, Who was he? He wrote a geography of this Coast. No idea when it was published.

But I know that it was considered famous nearly one hundred and fifty years ago. The only remark Malte made about our bit of the coast was ‘What has become of the famous city of Melinda, and the twenty churches of Mombasa?—do they exist?’ That’s cryptic enough, if you like. The famous city of Malinda. Up it pops again. I heard an unusual thing the other day. Of how Malindi got its name. From a source you’d never guess. From Uganda. This is the story. It comes from an old witchdoctor, queerly enough.

As you know the Bantu peoples of Africa originally came

from the country we now call Uganda and thereabouts. Because of sickness or drought, soil erosion or other causes they began to trek. Some tribes eventually reached the Cape, others came down to

this coast. One story says that these tribes were the llama tribes. Before their departure from their old haunts they agreed to each tribe taking the name of an animal. They would become blood

brothers to the animal they had chosen. They were not to kill their blood brethren, but other tribes could. The result would mean equal distribution of food.

ILAMA TRIBES

All over Africa tribes still retain their llama names. Some have changed almost out of recognition. But there are two tribes on this coast that have not changed. The Wajomvu and the Wadigo (Wadege). This latter chose the name ‘People of the Birds’. And within living memory the old women of the Wadigo tribe would not eat the flesh of a bird. It was their tribal llama.

So here we have two of the llama tribes. And people who know of these things say that when they listen at nights on the coast, the sound of the drums, the death and pepo dances, are almost identical to those they have heard in Uganda. And they also say that wherever the Bantu people went they took with them the old place names they were used to. The following are names from Uganda. Think of the coast names they resemble. Masindi, Kisindi, Bumbire, Ribo, Petta, Kilim and Bulinda. There are dozens of others . . . but Malindi might easily have been one of them years ago, don’t you think? Edward Rodwell

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Omotik, Ndorobo in Kenya

Introduction / History

Sliding through the dense forest, the mud-covered young Dorobo hunter stiffened suddenly as he heard unfamiliar voices ahead. Creeping forward, he spied a group of oddly dressed people talking to his fellow tribesmen. "Is this really the end of the world, is this the Jesus they talk about?" he pondered. Curious, he stepped into the clearing and walked cautiously toward them. He had just seen the first Jesus-sent people to his own home.

Click on Map

BANTU MIGRATION

The Bantu expansion or Bantu colonisation

The Bantu expansion or Bantu colonisation was a millennia-long series of migrations of speakers of the original proto-Bantu language group.[1] [2] The primary evidence for this great expansion, one of the largest in human history, has been linguistic, namely that the languages spoken in Sub-Equatorial Africa are remarkably similar to each other, to the degree that it is unlikely that they began diverging from each other more than three thousand years ago. Attempts to trace the exact route of the expansion, to correlate it with archaeological evidence and genetic evidence, have not been conclusive; thus many aspects of the expansion remain in doubt or are highly contested.[3]

Cont: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bantu_expansion

Introduction

Between 1000-1800 AD, East Africa experienced a wave of migrations from different parts of Africa. The Bantu from the Congo or the Niger Delta Basin were the first to arrive, followed by the Luo from Bahr el Ghazel in Southern Sudan and then the Ngoni from Southern Africa.

Cont: http://www.elateafrica.org/elate/history/bantumigration/bantuintro.html

After their movements from their original homeland in West Africa, Bantus also encountered in East Africa peoples of Afro-Asiatic (mainly Cushitic) and Nilo-Saharan (mainly Nilotic and Sudanic) ancestral origin. As cattle terminology in use amongst the few modern Bantu pastoralist groups suggests, the Bantu migrants would acquire cattle from their new Cushitic neighbors. Linguistic evidence also indicates that Bantus likely borrowed the custom of milking cattle directly from Cushitic peoples in the area.[16] Later interactions between Bantu and Cushitic peoples resulted in Bantu groups with significant Cushitic ethnic admixture, such as the Tutsi of the African Great Lakes region; and culturo-linguistic influences, such as the Herero herdsmen of southern Africa.[17][18]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bantu_peoples

http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/africa/features/storyofafrica/2chapter5.shtml

Hodi!—May I approach? Although most people answer with a ‘Karibu’, it is incorrect to do so. The answer is ‘Hodi’, followed by ‘Karibu’.—Come near. But the word ‘hodi’ has a far greater significance than merely as a greeting. Throughout the breadth of equatorial Africa, and right down to the Cape the word is used. And used in its deeper sense, with its back¬ground of mystery and miracle, it is more protective than the strongest stockade. For in the blue, an un¬answered ‘Hodi’ is never disregarded amongst peaceful folk ... it would invoke witchcraft to approach a house or shamba unless the answering hail was heard.

There is another aspect of the word. It affects the coast. In the very old days—when the llama tribes first came down the sea—legend has it (and it can easily be believed) that there was a great shortage of water along the coastline. Wells were difficult to dig with the primitive tools in those days. But when a natural spring was found, its appearance in a waterless country was thought to be miraculous. And springs were named ‘Hodi’—you are welcome. Even from that time to this whenever a spring is approached, the hail is given. There is one at Bamburi, which you might know, and there is another at Port Reitz. It’s name is ‘Hodi’! . . . and thereby hangs a tale. I’ll tell it one day. Edward Rodwell

Photographer of the Day: John Kenny’s African Beauty Series

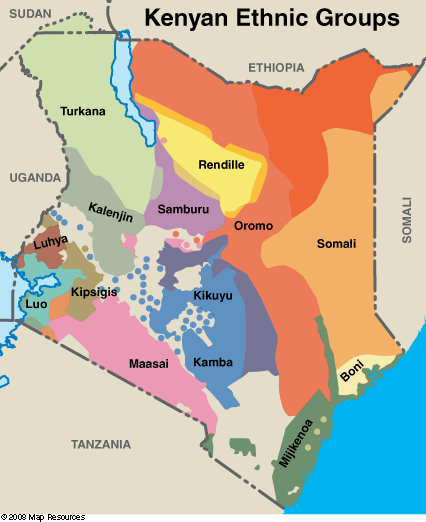

Tribes of Kenya

Tribes of Kenya

Click on Photo

However, most Kenyans speak at least three languages: their tribal language, Swahili (which has become a ‘lingua franca’ among a large part of East Africa) and English. Swahili (or Kiswahili) and English are the official languages of Kenya.

Language

Language, however, is the main criteria for a tribe. There are three main language groups in which the tribes in Kenya can be divided:

Bantu-speaking tribes:

Central Bantu: Kikuyu, Akamba, Meru, Embu, Tharaka, Mbere

Western Bantu: Gussi, Kuria, Luhya

Coastal Bantu: Mikikenda, Swahili, Pokomo, Segeju, Taveta, Taita

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Kikuyu

http://kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.co.uk/2012/11/kikuyu-people-kenyan-largest-and.html

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nilotic-speaking tribes:

Plains Nilotic: Maasai, Samburu, Teso, Turkana, Elmolo, Njemps

Highland Nilotic: Kalenjin, Marakwet, Tugen, Pokot, Elkony, Kipsigis

Lake River Nilotic: Luo

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Masai and Coloniasm

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Cushitic-speaking tribes:

Eastern Cushitic: Rendille, Somali, Boran, Gabbra, Orma

Southern Cushitic: Boni

Paukwa

Intro: Building a repository of positive, Kenyan stories ??

Dinka, a Wonderful Nilotic Ethnic Group from Sudan

Who are the Nilotes? Tallest, Darkest and Thinnest People on Earth

Introduction to Ancient Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush

SOUTH ASIANS AND THEIR LANGUAGES IN EASTERN AFRICA

Dr Abdulaziz Y Lodhi

http://opinionmagazine.co.uk/details/2202/south-asians-and-their-languages-in-eastern-africa

Other Useful links

http://opinionmagazine.co.uk/details/2202/south-asians-and-their-languages-in-eastern-africa

http://www.pambazuka.org/global-south/bantu-origins-sidis-india

History of Christianity in Kenya

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Kenya

http://www.dacb.org/history/beginning%20and%20development%20of%20christianity%20in%20kenya.html

THE EARLY HISTORY OF CHURCH COOPERATION AND UNITY IN KENYA

Kiswahili language

Swahili language, also called kiSwahili, or Kiswahili, Bantu language spoken either as a mother tongue or as a fluent second language on the east coast of Africa in an area extending from Lamu Island, Kenya, in the north to the southern border of Tanzania in the south. (The Bantu languages form a subgroup of the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo language family.)

http://www.britannica.com/topic/576136/websites

http://www.swahilihub.com/JifunzeKiswahili/-/1306806/1333292/-/jbyx02z/-/index.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swahili_language

http://www.glcom.com/hassan/swahili_history.html

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Peoples & Cultures

What is language?

Language is a body of words and the systems for their use common to a people who are of the same community or nation, the same geographical area or the same cultural tradition.

Kenya is a multilingual country. The Bantu Swahili language and English are widely spoken as the lingua franca, and are the two official languages. The major language families spoken in Kenya are the Bantu and Nilotic groups. There is also a Cushitic minority, besides Arab, Hindustani and British immigrants.

SIL Ethnologue (2009) reports the 12 largest communities of native speakers in Kenya as follows:

Bantu

- Kikuyu 7.18 million

- Kamba 3.96 million

- Ekegusii 2.12 million (2006)

- Kimîîru 1.74 million

- Oluluyia (listed as a macrolanguage) > 1 million

- Kigiryama 0.62 million (1994)

- Kiembu 0.43 million (1994)

Nilotic

- Dholuo 4.27 million

- Kalenjin (listed as a macro-language) > 1.5 million

- Maasai 0.69 million

- Turkana 0.45 million (2006)

A total disdain to the historical, migratory and linguistic historical facts that add to such

discussions by some.

Historical Archaeological excavations at early Iron Age sites that have provided detailed ceramic data as well as a radiocarbon-dated chronology which has been used to examine theories

proposed by linguists.

While there is considerable information available on the spread of early Bantu speakers, much less is known about the prehistory of non-Bantu languages, especially in Eastern Africa. In spite of this

fact, the problem of the origins of non-Bantu languages such as Cushitic and Nilotic has interested scholars for decades.

The Cushitic language belongs to the larger Afro-Asiatic family, which includes Arabic and other Semitic language group.

Although Swahili is widely used as a lingua franca in many countries, Swahili has also been greatly influenced

by Arabic; there are an enormous number of Arabic loanwords in the language, including the word swahili, from

Arabic sawāḥilī (a plural adjectival form of an Arabic word meaning “of the coast”).

A Swahili is here defined linguistically… as a speaker of one of the primary dialects of Swahili, namely, from north to south, both language and culture are ostensibly modified over the

centuries.

Therefore local African languages, Arabic, Indian, Farsi, etc text that have been around for centuries in the region, have all been contributors towards the Swahili language and therefore it is and

will be utilised by all East Africans no matter what their cosmopolitan back ground may be and how far their ancestral geographical route takes them across Africa as well as across the

oceans.

We must now turn our attention to the native peoples of the coast region. The natives who now live along the coast were not the original inhabitants. Countless ages ago the greater part of Africa near the Equator was inhabited by entirely different people from those of the present day. It is thought that these earliest inhabitants were a dwarf-like people. The only natives left at the present day who resemble these aborigines are supposed to be the Bushmen of the Kalahari desert, the pygmies of the Semliki forest and Ruanda, the Wata who live among the Gallas, and the Tomal, Yehir and Midgans who live among the Somalis.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00672708309511318?journalCode=raza20

Colonialism and its Legacies in Kenya, Peter ONdege Associate Professor of History Department of History, Political Science and Public Administration

http://international.iupui.edu/kenya/resources/Colonialism-and-Its-Legacies.pdf