Indians in East Africa

South Asians In East Africa - A Brief History

The easternmost region of Africa consists of countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. This region also consists of some well-known lakes and mountains: the fresh water Lake Victoria, Lakes Albert and Tanganyika, and Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro — the two tallest peaks in the region.

In her book Out of Africa, the Danish author Karen Blixen mentions that on a clear day she could see Mount Kenya from her house at the foot of the Ngong Hills. The other well-known landmark is the Great Rift Valley. But what really made this region of Africa a target for European exploration, exploitation and colonisation in the 19th Century was farming. But it was not just the Europeans who went there — there were Asians there, too.

Most Asians, both Hindus and Muslims went to Kenya from various parts of India in 1896, in the early days of British colonial rule. A lot of them arrived in dhows (traditional Arab sailing vessels) containing about 350 men. However, it is estimated that the British had taken more than 30,000 Asians, mainly of Punjabi (Indian) origin, to work as labourers, artisans and clerical staff on the Uganda Railway. This started in the eastern coastal town of Mombasa, in what is now known as Kenya1.

Once they had completed the work on the railway, a lot of the indentured labourers returned to India. But some remained. They were joined by hundreds of independent immigrants (mainly Indian Gujaratis and a few Goans) who arrived as shopkeepers, artisans and professionals.

Asians as well as Arabs were already in the region well before the Europeans, and doing business along the coast. It was they who enabled the European explorers and missionaries to make their way inside the continent.

The Coming of the Railways

The first railway, set on the island of Mombasa, was a two-foot trolley line that was operated by hand from the port. By 1896, everything was in place to build a railway line all the way up to the area of Port Florence, now known as Kisumu.

Building it was made a little easier by the fact that the gauge used to construct the line was already in use in another part of the British Empire: in India. This meant there was a ready source of locomotives. But as the line left Mombasa it had to cross an area that was waterless, the Taru Plains. This slowed down the process, as every single drop of fresh water had to be taken to the workers' camps by train.

In 1898, the railway line reached the Tsavo River. The line was first carried across the river by a supporting wooden framework, while a bridge was being built under the direction of captain JH Patterson, who went on to become a Lt Colonel.

But soon construction of the bridge was held up by two man-eating lions attacking the camp.

Despite it being fenced-off with thorn barriers, fires being lit, and strict curfews imposed after dark, the lions still managed to drag men out of their tents at night and kill them. The victims were mostly Asians, plus some Africans. As the attacks continued, the fear increased. Many workers became superstitious and believed the lions were evil spirits. Patterson faced the challenge of maintaining his authority, even his personal safety. It was at this time that Patterson, experienced in tiger-hunting through military service in India, decided to take action.

On the night of 9 December, 1898, he shot the first lion, and then the second on the morning of 29

December2. He was immediately declared a hero by the workers, including those who had threatened to kill him. They presented Patterson with a silver bowl as a token of appreciation for the risk he had taken on their behalf.

News of killing of the lions began to spread like a fire being fanned by wind. It was even mentioned in Britain's Houses of Parliament by the then Prime Minister Lord Salisbury.

Soon the building of the bridge recommenced, as did the railway line. But this was not the last time lions would disrupt the work. In 1899, a road engineer was dragged from his tent near Voi and killed. Then in 1900 a police superintendent who was sleeping in his observation saloon was killed when a lion entered his carriage, dragged his body through a window and ran into the bushes.

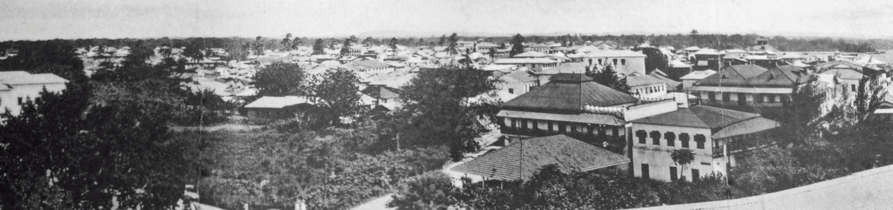

By 1899, nearly 500km of track had been laid and the line crossed the Athi plains, and the river. It soon reached an area of swampy ground, then known by the Masai tribes as 'Nyrobi' (now Nairobi, the capital of Kenya). A major depot was then constructed, the administrative offices relocated from Mombasa, and homes built for the staff.

As the construction of the railway continued, this attracted Asian merchants, and goods and services began to flow to the workforce. The line finally reached Port Florence (Kisumu) on 19 December, 1901.

South of Kenya, in what was then known as Tanganyika, now Tanzania3, the Germans started to construct a line from the coastal town of Dar es Salaam in 1904. This reached the town of Kigoma in the west, on the eastern shores of Lake Tanganyika, in 1914.

A line was then built from Tabora, situated in the centre of the country, to Mwanza in the north, on the southern shores of Lake Victoria. This was completed in 1928.

Also in 1904, another line which had commenced from Tanga in 1899 reached Mombo. It then continued to head towards Mount Kilimanjaro, reaching the town of Moshi in 1911. This line was finally linked to the Uganda Railway at Voi in 1924. Today, the railway goes right up to the border between Uganda and The Democratic Republic of Congo, and also to southern Sudan.

Most Asians went to Kenya not just as individual, freelancing adventurers but members of existing communities. The history of Asians in Kenya can be traced to a few original immigrants who settled and were successful and then returned to India, only to return to Africa with members of their family. This is considered traditional in such Indian societies, and was strengthened by the immigrants' position as strangers in a strange land.

The Asians were forbidden by law from owning farmland. They settled in townships such as Kisumu (situated on the shores of Lake Victoria), Eldoret, Kajiado, Athi River, Kitale, Nakuru, Naivasha, Makindu - just outside Mombasa - Voi, Mombasa, Machakos, Thika, Nyeri, Limuru and Nanyuki, and then to the suburbs of areas of Nairobi such as Parklands, Westlands, River Road (also known as Grogan Road) and Ngara. Not only did they live in these towns and areas, in some cases they built them and became urbanised.

The concentration in towns went on to facilitate the development of community associations as well as services. This enabled each community to establish its own places of worship and schools, centres which provided focal points for these Asian's communal lives. They later moved into 'posher' areas of the city, such as Karen (named after Karen Blixen, whose pen-name was Isak Dinesen), Lavington and Muthaiga. Basically, Asians were self-sufficient - socially and spiritually — and, above all, extremely successful economically. It was the latter that led to resentment among the Africans.

The First World War

In 1914, when the First World War broke out, the German colony chief administrator, governor Heinrich Schee, and the governor of Kenya, Sir Henry Conway Belfield, ordered 'no hostile action to be taken'. The reason was that neither had any troops. Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck, the commander of a tiny German army, ignored this and assembled his men. Fighting in East Africa actually began when German troops in Rwanda and Burundi began shelling villages in what was then Belgian Congo (now The Democratic Republic of Congo).

But it was not until September that action was seen in British East Africa, when the Germans staged raids into the area of Kenya and Uganda. Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck created a small navy on the shores of Lake Victoria. It caused little damage but big news. In response, the British authorities despatched gunboats, which were loaded onto trains in small pieces and transported on the Uganda Railway. Simultaneously, two brigades of the British-Indian Army tried to land at Tanga in German East Africa on 2 November, 1914, but failed. The landing was disrupted when the Germans retaliated with heavy and accurate firing.

In 1916, General Jan Smuts, who had a large army consisting of 13,000 South Africans, including Boers, British and Rhodesians, and 7,000 Indian and African troops, was handed the task of defeating the Germans. He also had access to a small Belgian force and some slightly larger but ineffective Portuguese units which were not under his direct control and based in Mozambique. But this was a purely South African operation.

Smuts' army was attacked from several directions, but mainly from north of Kenya. In the meantime, a substantial force from Belgian Congo moved from the west over Lake Victoria and into the Rift Valley. Another force moved over Lake Nyasa, now known as Lake Malawi. The aim of all of these forces was to catch von Lettow-Vorbeck. They failed largely due to disease. However, one advantage had been gained: the capture by the British of the German railway from the coast at Dar es Salaam to Ujiji. This enabled the Belgian forces to capture Tanga — an administrative centre of central German East Africa.

Despite efforts to capture and destroy von Lettow-Vorbeck's army, the British had failed to end enemy resistance. But even though the Germans had been able to 'down' some large British forces, in 1917 the situation slowly began to change. British troops finally closed in on their enemy and on 23 November, 1917, Lettow-Vorbeck was forced to cross into the Portuguese territory of Mozambique. By doing this, he had hoped to gain recruits and capture small villages and supplies.

For the next few months, although Lettow-Vorbeck managed to avoid capture, he was unable to gather strength. Finally, in August, 1918 the German army crossed into Northern Rhodesia, now known as Zimbabwe. Two months later, two days after the guns fell silent in Europe and the armistice was signed at the hall of mirrors at Versailles, Paris, the Germans began what was to be their final attack, 'burning' their last town. The next day they were informed about the signing of the armistice.

During the war, while European settlers continued to arrive and farm, now coffee as well, so did Asians. Although there were places in Kenya where non-Europeans were not allowed to go or live, some Asians found employment in these areas and were therefore tolerated. Some Asians went back to India, returned with family members and set up their own businesses, such as shops. These were initially congregated in small areas that became known as 'River Road' (previously known as Grogan Road) and 'Indian Bazaar'.

The Second World War, the Mau Mau Uprising and Independence

The Second World War saw some action in the region - more so when the colonial authorities brought in a Punjab regiment from India. During this time the East African campaign pitched the forces of the British Commonwealth of Nations against those of the Italy. The British troops came under the control of British Middle East Command.

There were times when coastal cities such as Dar es Salaam (which had been handed over to Britain as a League of Nations mandate at the end of the First World War) came under aerial bombardment from aircraft taking off from carriers in the Indian Ocean. But the campaign did not last as long as in Europe, the Middle East and Far East, and ended officially in September, 1943 when the Italians signed an armistice with the Allies. However, some people were not aware of this and continued to fight for another month.

The struggle for Kenyan independence began almost immediately after the Second World War, and was led by the Kikuyu tribe.

Prior to the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s, European settlers took over lands in the central highlands which were mainly inhabited by the Kikuyu. By 1948, the Kikuyu were restricted to 2,000 square miles, while the settlers had 12,000 square miles and the most desirable agricultural land. Also, the climate in the central highlands was cool compared with the other areas of the colony. This led to political, economic and racial tension. The Kikuyu Central Association called for an 'oath of unity' - a ceremony which enabled members to take an oath to at first to be involved in civil disobedience, and then to fight and defend themselves against the Europeans.

The oath-taking ceremony sometimes included animal sacrifice and the ingestion of blood. Some places of ritual were decorated with intestines and goats' eyes, and there were promises to kill, dismember and burn settlers. But the oath-taking ceremonies did not just take place in Nairobi — but several miles outside the city as well. This became known as 'Kenya Emergency' and troops were sent to the colony. People were being killed in broad daylight, as well as at night, the houses of settlers set on fire, and their livestock hamstrung.

On 20 October, 1952 governor Baring declared a state of emergency and 'Operation Jock Stock' was enforced. At the same time 100 leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta, who would later become the first President of Kenya, were arrested. It was hoped that this would lead to the state of emergency being lifted within several weeks. But it was not to be - the violence increased.

Asians imposed a 'curfew' on themselves and only ventured out to work or when strictly necessary. On 12 December, 1963, Kenya became independent and Kenyatta, who was released from prison, was named Prime Minister, and a year later President.

Tanganyika received its independence on 9 December, 1961. Three years later it merged with the island of Zanzibar and became known as Tanzania. Uganda received its independence on 1 March, 1961.

Exodus and the 'Rivers of Blood'

Towards the end of 1968, there was panic within the Asian community in Kenya as the government pursued its 'Africanisation' policy, which many believed was designed to push Asians out of the country. The government said their work permits would not be renewed, and they were restricted to certain sectors of the economy. Asians working as civil servants were forced out of their jobs. Not only did this cause panic but a problem for the former colonial power.

In Britain, the Conservative Party of Harold Macmillan had previously guaranteed Asians holding British passports unlimited entry into the UK. Under Harold Wilson's Labour government things changed. Home Secretary James Callaghan announced the government would no longer allow this, so aeroplanes carrying mainly Asian passengers from Kenya were turned away.

The 1968 Commonwealth Immigration Act introduced the requirement that immigrants demonstrate a 'close connection' with the UK. This caused a cabinet split. Not only was there criticism of the bill but growing tension on the issue - provoked by Enoch Powell and his famous 'rivers of blood' speech in April, 1968, which brought the immigration issue to the fore. This ultimately led to the Race Relations Act of 1976.

In 1969, six years after Kenya became independent, the Trade Licensing Act came into existence. Non-citizen traders had their licences revoked as a part of the government's policy of promoting citizen businesses as 'African'. This became popularly known as 'Africanisation' and led to many

Asians selling their businesses to Africans. Some even closed them if they were unable to sell and went to live in the United Kingdom. They had British overseas passports and were considered British overseas citizens.

More:

http://h2g2.com/approved_entry/A32016241

http://coombs.anu.edu.au/Biblio/biblio_sasiadiaspora.html

15 things you need to know about Indians in Africa

http://www.africlandpost.com/15-things-need-know-indians-africa/

Asians In East Africa - A Brief History by Pratik J. Jasani

The easternmost region of Africa consists of countries such as Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. This region also consists of some well-known lakes and mountains: the fresh water Lake Victoria, Lakes Albert and Tanganyika, and Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro — the two tallest peaks in the region.