The 1868 expedition to Abyssinia

Apparently the first East African Railways was constructed during the British expeditions to Abyssinia in 1867-8. This line too was built by Indian labourers this was the 5’6” Indian Broad gauge. The British Expedition to Abyssinia was a rescue mission and punitive expedition carried out in 1868.... A railway, complete with locomotives and some twenty miles (32 km) of track, was to be laid across the coastal plain, and at the landing ...

Indian Army

10th Regt of Bengal Lt Cavalry

12th Regt of Bengal Cavalry

3rd Regt of Bombay Lt Cavalry

21st Punjab Regt Bengal Native Infantry

23rd Punjab Regt Bengal Native Infantry (Pioneers)

2nd Bombay Native Infantry (Grenadier)

3rd Bombay Native Infantry

10th Bombay Native Infantry

21st Bombay Native Infantry (Marine)

25th Bombay Native Light Infantry

27th Bombay Native Infantry (1st Baluch)

No 1 Company of Bombay Native Artillery

Corps of Madras Sappers and Miners

Corps of Bombay Sappers and Miners

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Expedition_to_Abyssinia

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194554

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armycampaigns/africancampaigns/campabyssinia.htm

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/abyssinia

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194553

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armycampaigns/africancampaigns/campabyssinia.htm

Ethio-Djibouti Railways

The Ethio-Djibouti Railway (French: Chemin de Fer Djibouto-Éthiopien (C.D.E.) is a metre gauge railway in the Horn of Africa that once connected Addis Ababa to the port city of Djibouti. The

operating company was also known as the Ethio-Djibouti Railways. The railway was built in 1894–1917 to connect the Ethiopian capital city to the then-French colony of Djibouti. During early

operations, it provided landlocked Ethiopia with its only access to the sea. After World War II, the railway progressively fell into a state of disrepair due to competition from road transport.

India pledges 300 mln dollars for Ethio-Djibouti railway .... It was constructed by the French for the Emperor, Menelik in the early 1900s. .... CCCC (1800), a Chinese

government-owned transportation infrastructure company, will be ... China's CCECC completes track laying of Ethiopia- Djibouti railway.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethio-Djibouti_Railways

_________________________________________________________

The Beginning

The presence of Indians in East Africa (Coastal known as Zeng or Zenj) is well documented in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea or Guidebook of Red Sea by an ancient Greek author written in 60

AD.

1593 Indian masons were employed for the construction of Fort Jesus in Mombasa.

The Berlin Conference of

1884-5, which regulated European

colonization and trade in Africa, is seen as emblematic of the "scramble".

October 1885, limits of Sultan of Zanzibar’s sovereignty, and the delimination of the “spheres of influence” of Great Britain and Germany in East Africa began.

From 1880-1890 ..it was IBEAC that was in persuit of demarcations along the Victoria Nyanza.. Agreement with the German

East Africa Company was not easy until around 1893. Another meeting leading to the 'Heligoland Treaty', was held in 1890 to ensure Africa 'The benefits of peace and civilisation' and settled the last

disputes which still existed between Britain and Germany who abandoned some places in Kenya, receiving in compensation the Island of Heligoland in the North Sea.

On 3 March 1885, the German government announced that it had granted an imperial charter, which was signed by

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck on 27 February 1885. The charter was granted to Peters' company and was intended to establish a protectorate in the African Great Lakes region.

1885: German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika) was colonized by the Germans in 1885. The territory itself spanned 384,180

square miles (995,000 km2) and covered the areas of modern-day Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania.

1886 IBEAC was in persuit of demarcations along the Victoria Nyanza.. agreement with the German East Africa Company.

25th May 1887, Sultan Bargash granted to the East Africa Association a concession for a period of 50 yrs.

1888; Imperial British East Africa Company obtained , a Royal Charted from her Majesty on Sept 3rd

1888

1888 the Imperial British East

Africa Company established claims to territory in what is now Kenya.

1889: IBEAC recruited 300 Indians from Delhi on 3 yrs contract..police the whole of the company’s

territory.

In 1890 and 1894 British protectorates were established over the sultanate of Zanzibar and the kingdom of Buganda

(Uganda).

1890: Another meeting leading to the 'Heligoland Treaty', was held in 1890 to ensure Africa 'The benefits of peace and

civilisation' and settled the last disputes which still existed between Britain and Germany who abandoned some places in Kenya, receiving in compensation the Island of Heligoland in the North

Sea.

1890 AMJ (Alibhai Jeevanjee) arrived in Mombasa

1891: 24 inch gauge, Central Africa Railways of I.B.E.A to Kipevu from Mombasa was already in place by 300 Indians from Delhi,

obtained strict permission from the Foreign Office and Government of India.Indians were restricted also to take up contracts in German East Africa.

In December 1891 Captain James Macdonald began an extensive survey which lasted until November

1892….

1891:The German East Africa Company was dissolved and Imperial Administrative established.

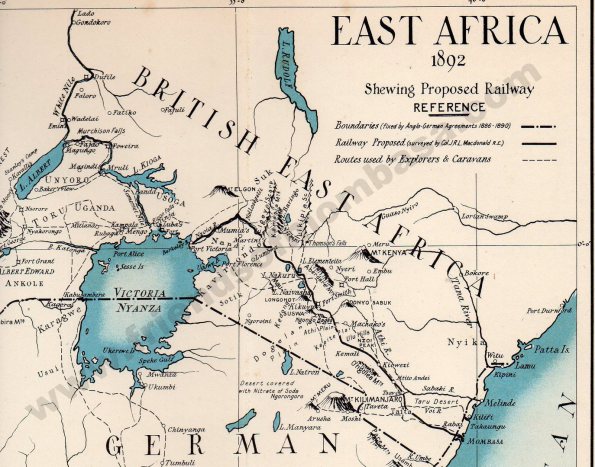

1892 Shewing Proposed Railway was produced.

1893: British East Africa ( I.B.E.A) came to be…

1893: German East Africa was formed

1893: MacDonald’s report of 657miles from Mombasa to Port Victoria …recommended 3’6” gauge.

1895 the company’s territory in Kenya was transferred to the crown as the East Africa Protectorate (after 1920, the Kenya Colony

and the Kenya Protectorate).

1895: London committee of, chaired by Percy Anderson to supervise construction of Uganda Railways was confirmed.K.A.R

(Kings African Rifles) was also formed, K.A.R Nubians in Uganda and other parts were utilised…

1895 15th Oct Secretary State for India was approached by the GB Railways committee to provide facilities for the recruitment of

labour…First it was necessary to pass an amendment to the Indian Emigration Act in order to schedule East Africa as a country to which the emigration of labourers from India, to work under agreement

for hire, could be permitted. At close of contract, if he preffered to do so, and to forfeit his right to return passage, amendment of conditions were made, to task workers or piece-work if

required.2000 coolies were selected, masons, carpentars, smiths and clerks, surveyors and draughtsmen at average 30 rupees/40 shillings per head per month.

1895 September George Whitehouse was appointed chief engineer of an ambitious plan to build a railway from the coast

of Mombasa inland to Kisumu (Fort Florence),

and embarked at Mombasa with his team in December

1895.

Jan 1896 arrival of Indian workers for the building of Uganda Railways..107 Europeans, 169 Goans and Euroasians,:5,962 Indians,

of whom 4,799 were Punjabi Muslims coolies and 300 were soldiers, 494 Bauchis, 596Arabs,14,574 Swahilis,, 2667 Slaves,, 1,500 native priso a total population 24,719..

An emphatic 1897 expedition by …. Lieut. R. Bright, Capt. Macloughlin D.S.O,. Major Austin, R.E., .Lieut Hon .A. Hanbury Tracy,

Capt Fergusou D.S.O and Col. Macdonald.

Recruitment by Alibhai Jeevanjee , Karachi, Bombay and (Marmagoa in 1902)

from Punjab and Gujurat, 7000 remained behind after their contractual works ended….1914-34,000 indians were recorded to be in Kenya/Uganda known as British East Africa.

1914-1918 World War …Great Britain and Germany were at War (Kenya and Uganda/Tanganyika)

Under the Treaty of

Versailles (signed June 1919; enacted January 1920), Britain was awarded the former German territory of Tanganyika as a League of Nations mandate.

All of these above named territories achieved political independence in the 1960s, and Zanzibar united with Tanganyika to form Tanzania in 1964.

Indentured Labour

As per reported on Indentured labour, Coolies: How Britain Reinvented Slavery tells the astonishing and controversial story of the systematic recruitment and migration of over a million Indians to all corners of the Empire. It is a chapter in colonial history that implicates figures at the very highest level of the British establishment and has defined the demographic shape of the modern world.

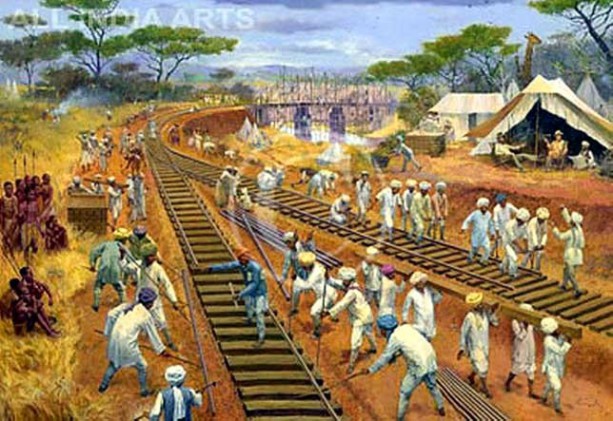

Uganda Railways was built by Indentured labourers, they were brought in from occupied Indian Sub-continent, yet we were a threat to them in every way possible in terms of out doing and out pricing them..

Winston Churchill hated the Indians, in fact he killed millions in innocent men , women and children, yet he is seen as national heroic figure to this day..

If one reads the book” A Colony in the making” by Lord Cranworth you will fully understand how racist towards the Indians and the indigenous people these pathetic colonials were and were actually openly proud of it at all times, they did not shy in expressing themselves in many different ways in putting pen to paper either.

One only has to have a look at the Nairobi town planning, that in it-self tells a lot…

They were prejudice in every way possible from the time when Kenya was taking shape, all Europeans/settlers locating into Colonial occupation were helped financially and also favoured through subsidies in the building of Kenya for settlers.

Prejudice took place through and through, in its infrastructure, Its Judicial, its institutes, its hospitals and health workers, its land offices, its farming, its allocation of prime land…etc...

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 1-10

BY LIEUTENANT R. BRIGHT, RIFLE BRIGADE.

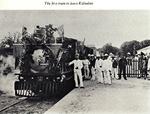

An emphatic 1897 expedition by ….The author, Lieut. R. Bright, Capt. Macloughlin D.S.O,. Major Austin, R.E. Seated…,…. .Lieut Hon .A. Hanbury Tracy, Capt Fergusou D.S.O and Col. Macdonald, with Indian made Wagons, Water Buffaloes, route that is taken from Mombasa meeting en-route with Indian Soldiers (Uganda Rifles), Expedition with the Masai, the Swahili, mixed porters of different tribes, , through Taru Desert, crossing River Tsavo, Equator camp, Lake Baringo, Mumias, towards Lake Rudolf ….etc

This is a most captivating account of the MacDonald Expedition of 1897 - 1898, where the unknown region between Lake Rudolf and the Nile was traversed. MacDonald and his men discovered the characteristics of this unknown country, measured its mountains, and interacted with the locals. For nine months however, the expedition was forced to abandon its own work in order to turn its whole strength of men and material to the assistance of the Uganda Protectorate, which was threatened with destruction by the revolt of the Sudanese troops. This comprehensive report discusses the fighting and casualties, and provides much detail on the survey expedition that followed, on the relations with various tribes, and also mentions other historical expeditions in and around the region, such as that of Emin Pasha.

A narrative of the travels of the important Government expedition under Colonel Macdonald in the very heart of the African Continent. With a complete set of snap-shot photographs, taken by the author, illustrating many phases and incidents of life en route. Practically it is to Colonel Macdonald that the British Empire owes the possession of the vast territory commonly known as Uganda.

After leaving the Uganda Railway, of which, in 1897, only seventy miles had been constructed, the Macdonald Expedition was divided into three columns. The first, consisting entirely of porters, was under the command of Colonel Macdonald himself, while the other two columns were made up of waggons drawn by bullocks, and their attendants. The road made by Captain Sclater was followed.

For the first four days there was practically no water, the road leading through the Taru Desert. All the porters, however, were provided with water-bottles, and a water-waggon accompanied the caravan for the first two marches; while, to make assurance doubly secure, as many mussocks full of water as possible were carried in the waggons.

In spite of these precautions, however, my boy came to me one night, and plaintively declared he had had no water to drink for two days; I gave him all I could spare.

It proved to be literally, a “ stirrup-cup,” for, having obtained a supply of the precious fluid, the young rascal promptly deserted and returned to Mombasa.

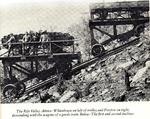

The first water we came to was the River Tsavo, which it took the expedition many hours to cross. Fortunately, the water did not come above the axles of the waggons, so that the loads did not require to- be unpacked and carried across—for which we were devoutly thankful. The photo, reproduced below shows one of our “gharris,” or Bombay country carts, crossing the river, assisted by Sikhs and Swahilis. These carts were specially brought from India for the use of the expedition, and proved eminently serviceable. They are light and can be man-handled.

Mention of the River Tsavo reminds me of a rather comical incident. The country near the river had the reputation for affording good shooting, but so far very little game had been seen. One of our party, getting impatient, went out one morning vowing that he would not return until he had killed something. The manner in which he fulfilled his vow was decidedly curious. A poor water buffalo, after having come from India through the worst of the monsoon, and no doubt severely tried by the hard marches and scarcity of water, had wandered some distance from the camp in search of rest and quiet. Presently he lay down in a shady spot for a peaceful “ forty winks,” little dreaming that he was being stalked by our sportsman colleague. At any rate, he was rudely awakened from his slumbers by an express bullet behind the shoulder, and, on looking round to ascertain the cause of this unkind treatment, he received another ball in the neck which finished him. He never drew a cart again. Our porters, who subsequently ate him, were no doubt perfectly well satisfied, but I do not think that the sportsman was altogether proud of his “ bag.”

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 2-10

We followed the cart road for some 400 miles, through somewhat uninteresting country. The nature of this “road” may be best judged by an examination of the above photograph, which shows one of our bullock- waggons crossing one of the swamps which intersect the track. The cart was loaded with three sections of our steel boat, securely fastened in a substantial crate. This craft was a whale-boat, intended to be placed on Lake Rudolf to keep up communication between the north and south ends of the lake. It was 25ft. long, and was carried the whole way from the coast in ten separate sections. For the first 400 miles it was packed in crates on the waggons, as seen in our photo.; but beyond that point its parts were shouldered by the Swahili porters, each section being slung on bamboos and carried by two men, who generally carried the pole-ends on their heads. The boat, however, owing to the outbreak of the Soudanese mutiny, never reached its destination, but was left on Lake Victoria for the use of the Uganda Administration. At Ngara Nyuki, our next halting- place (sometimes called Equator Camp, because it is almost exactly on the line), we were joined by the Uganda Rifles, who were to form the main part of the escort. The Soudanese on joining were very discontented ; they had just come through an arduous campaign, and had an aversion to starting off on an expedition the very destination of which they did not know. And they had another very real grievance. The particular three companies to which they belonged generally had to do most of the fighting in the Protectorate, whilst the other detachments of the regiment remained in garrison in peace and plenty. How, finally, they deserted the expedition and marched to Lubwa’s is now a matter of history, as is the subsequent battle on the high ground overlooking the Victoria Nyanza. Here the pursuing Colonel Macdonald, with a small force consisting of nine Europeans, seventeen Sikhs, and 340 partially-trained Swahilis, was attacked by the mutineers. He beat them off, and drove them back in disorder to Lubwa’s Fort, which they had seized the night before. By this signal victory there can be no doubt that British prestige was saved and the Uganda Protectorate preserved to the Empire. Fighting continued round Lubwa’s until the beginning of 1898, and during the whole of this period the exploring work of the expedition was at a standstill. The indefatigable Macdonald was here, there, and everywhere — fighting, pacifying, and avenging; until at last, during his absence, the mutineers—the primary cause of all the trouble—escaped in a dhow across a bay of the Victoria Nyanza. They were, however, pursued and defeated. Mwanga, the rebellious ex-King of Uganda, having been signally smashed about the same time, the expedition was at liberty to resume its long- delayed journey towards the unknown north.

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 3-10

The caravan marched in single file, as the next snap-shot shows; and, as long as they kept well together, the men were allowed to march pretty much as they pleased. In front of the long, straggling column went the advance guard, composed of Sikhs and native soldiers, accompanied by an officer. Then came the porters, as we see them in the photo., nearly all armed with Martini-Henry rifles and sword-bayonets. Each company of porters had a drummer, and these “ instrumentalists ” marched together in the fore-front of the caravan. I was lucky enough to obtain a very characteristic snap-shot of two of these curious musicians, and it is here reproduced. The bundles on their heads are their personal belongings, usually consisting of the weirdest possible assortment of odds and ends. Their water-gourds are strapped outside, and their sleeping - mats and food are made into a roll and tied round with a piece of string. All the porter’s worldly belongings, be they ever so cumbrous and unwieldy, go into this bundle on his head. Even if he possesses a live fowl—the acme of his ambition —he ties a piece of string round its leg and fastens it to his load. These drummers have different “ beats ” for different occasions—a regular telegraph-code, in fact; so that the porters in their rear know when camp is near, or when there is a river to be crossed, or a halt for rest is about to be called.

For several days the column marched along the western shore of Lake Baringo, a snap-shot of which—probably the first ever taken—is here given. Lake Baringo is a fresh-water lake, some forty miles in extent, belonging to the great chain of Central African lakes. It is situated four hundred miles in the interior— four marches to the eastward from the Uganda road. The inhabitants of the lake shores are known as the Wa-Njemps, a peaceful and industrious tribe, who have a few canoes on the lake for fishing purposes.

As there are no crocodiles in Lake Baringo, our men indulged to the full in bathing, a luxury of which they were very fond; and a couple of more or less merry bathers may be seen disporting themselves on the right in the photo, under consideration. There were a few hippopotami in the lake, and lions abounded round the flat, marshy shores.

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 4-10

One night a sentry posted to look after the cattle was struck down from behind by a lion and seriously mauled, but the brute was driven off before any harm was done. The man, in spite of his terrible wound (he was badly scalped by the brute’s claws), recovered rapidly, and was soon able to go about his duties once more. A little while after, whilst in charge of a small- party who were carrying letters, this same man had another thrilling lion adventure. The whole party were attacked in their little camp by a troop of lions, and only succeeded in driving them off after the expenditure of some three hundred rounds of ammunition, which was proved by an examination of their pouches! The deadly aim of the men and the fierceness of the fight will at once be apparent when I add that no damage was done on either side !

But this was by no means the last of our rencontres with lions, which seem to fairly swarm round the lake. A party of five porters deserted soon after passing Lake Baringo, intending to make their way back to the coast. But Nemesis was on the track of these sinners. Whilst sleeping under a tree they were suddenly surprised by lions, and had barely time to climb up into the branches before the hungry brutes were upon them. Then, and not till then, did the unfortunate men realize that in their excitement they had left their rifles—their only means of salvation—at the foot of the tree. Apparently fully understanding the helpless condition of their victims, the lions waited patiently until, one by one—worn out with hunger and exhaustion—the poor fellows dropped down on to the ground, only to be instantly torn to pieces and devoured before the eyes of their horrified companions. Only one man survived to tell the dreadful tale, and he re-joined one of the columns of the expedition some months later.

Wherever possible, guides were procured from the natives ; and the next photo, shows a group composed of three guides and the same number of Masai warriors. These particular guides came from Njemps, a large village to the south of Lake Baringo; and before they started from their homes they led us to believe that they knew every inch of the way. This proved to be very far from the case, however; but they did succeed, notwithstanding the thick bush, in piloting us as far as the next native settlement, where fresh guides were procured. The victualling of the expedition was, of course, a vitally important matter ; and for this purpose we had to take along with us large herds of cattle, to say nothing of immense stores of flour, and sometimes water. We engaged a number of Masai to look after the cattle, and during the whole time—in spite of the manifold difficulties of the route, and the fact that sometimes they had as many as 400 head to drive— they never lost a single beast. On the way back we paid each man off at his own village, giving him two cows as a reward for his fidelity. These Masai are a warrior race, and replenish their herds of cattle by the delightfully simple, if somewhat questionable, method of raiding their weaker neighbours.

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 5-10

As a rule, we bought flour from the natives in exchange for beads, cowries, cloth, or wire. A one-pound tobacco tin was used as the standard measure, and this, piled high with flour, was a porter’s ration for two days. As is the universal custom in East Africa, the higher a man’s rank the more food he is supposed to require; there-fore the headmen received double as much food as a porter. The giving out of the rations was called “ Posho,” and the ceremony is well illustrated in the photograph reproduced above, which shows the headman filling the flour-tins.

Sometimes as much as ten days’ food is given out at a time, and this is carried by the man himself; it is for him to see that it lasts the right number of days. At first the men were inclined to eat up their ten days’ food in half the time, hoping that when it was exhausted they would be given more. This caused considerable inconvenience and suffering in the early days of the expedition. But, later on, when they got to understand the difficulty of carrying more food than was absolutely required, they did their best to make their rations last over the allotted period.

Elephants were very numerous in some parts of the country, and in the next illustration we see a native carrying a large piece of elephant meat. Swahilis, although as a rule not very delicate feeders, will rather starve than eat either elephant or donkey meat. The natives, however, did not share this aversion, and whenever an elephant was shot they would assemble rapidly and attack the carcass with their spears .and small knives, cutting off pieces and eating them raw in fearsome style. Some would get right inside the huge carcass, carving out quite a little cave for them-selves.

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 6-10

Curiously enough, elephants seem to have a great animosity towards donkeys, as is shown by the two following incidents which came under my own observation: A number of loaded donkeys were being driven along, when suddenly a small herd of elephants came out of the bush. Without the slightest provocation a large bull elephant made straight for one of the poor donkeys and tossed him bodily into the air, afterwards carefully destroying the bales of food with which he was laden. The poor donkey died the same evening—probably from internal injuries received in the tossing process.

On another occasion one of my brother officers was stalking an elephant, his riding-'donkey being led behind him. Suddenly, in the exasperating way that donkeys have, the brute began to bray, and the elephant, hearing this, charged down upon poor Neddy. The man leading the donkey promptly dropped his rifle and fled, while the donkey also made tracks, faster than ever he had done before in his life, hotly pursued by the elephant. By a clever double, the donkey eluded the big tusker, which then retraced its steps and came across the discarded rifle. This the elephant picked up, and, waving it in triumph, disappeared in the bush. Neither elephant nor rifle was ever seen again.

The next photograph reproduced has a pathetic interest. When one of the columns of the expedition reached the north shore of Lake Rudolf, the natives who live on the banks of the River Omo were found to be in great distress. They had been raided a few months before by bands of Abyssinian horsemen, who, coming down both sides of the river, had destroyed all their crops, burnt their granaries, and driven away their flocks and herds. Dead bodies were lying unheeded in the almost deserted villages. These people, some representatives of whom are shown in our illustration, were in a starving condition, and were, besides, suffering from smallpox. When asked what they had to eat, the poor creatures pointed first to their stomachs, round which thongs of leather were tightly bound to stave off the pangs of hunger, and then to the river—signifying thereby that they subsisted on what fish they could catch. On the left of this famine-stricken group is our guide. This man was rather a character in his way. He was very fond of snuff, and even pinches of Cayenne pepper, surreptitiously administered, did not appear to upset his equanimity. His nasal organ was indeed quite useful to him, for even when given a little tobacco he preferred to smoke with the mouthpiece of the pipe up his nose!

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 7-10

Providentially only one case of smallpox occurred in the caravan; so we were spared the awful suffering and wholesale decimation which would inevitably have occurred had this dread disease once taken hold on our men.

There being no food to be had in this part of the country, the expedition had now to beat a hasty retreat. We managed to get a small supply from the inhabitants of the north-west shore of the lake, and this was just sufficient to enable the caravan to continue on the return journey for some thirty days. On the very day when the last of the food had been consumed, and things were beginning to look desperate, we fell in with Lieutenant Hanbury Tracy’s column, much to our delight. Major Austin had, fortunately, foreseen the difficulty of obtaining food for the return journey, and a column had been sent back to Mount Elgon some two or three months previously, to bring up fresh supplies for the Rudolf column.

News was here heard of Colonel Macdonald, who had had an adventurous journey into the Nile Basin. He had reached Tarrangole, the capital of the Sultanate of Latuka, where he had been cordially received by the natives. The Sultan of Latuka was an eminently diplomatic gentleman, who aspired to be on good terms with everybody. He possessed an old Egyptian flag, but when “ political considerations ” required it, he exhibited a Dervish standard, and clothed his minions in the patched “ jibbas ” of Mahdism. The next white man who visits this accommodating monarch will find that his collection of international emblems has been increased by the addition of a brand-new Union Jack, which will doubtless be displayed in the stranger’s honour.

There are a large number of caves in the lower slopes of Mount Elgon, and these are inhabited by the natives, who drive in their cattle every night for safety, the entrances being strongly stockaded. Several of these natural fortresses had to be stormed in order to punish the inhabitants for outrages committed on members of the expedition. On the alarm being given, by means of horns, the flocks would be driven into the caves and a heavy discharge of arrows kept up from the darkness of the interior. Several of our men were wounded whilst engaged in cutting down the defensive stockade, and a Soudanese corporal, who was struck in the neck, died shortly afterwards from the effects of the poisoned shaft.

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 8-10

The natives of Ketosh inhabit the country to the south-west of Mount Elgon. They are a warlike race, and caused considerable trouble to bring into subjection.

Some years ago a small party of men belonging to the Government station at Mumia’s were murdered by these people, and a punitive expedition was sent against them. On the storming party entering the village, the huts were found to be separated from each other by fences of brushwood.

Our next photograph shows a Ketosh village forge, where spear-heads, hoes, and pipe-stems are manufactured. The apparatus is wonderfully simple and withal efficient. Two mud-pipes, converging into one close to the furnace, serve to conduct the draught, and these are covered with goat-skin, into which a stick is fixed. A native sits at the end, and moves each skin backwards and forwards alternately, thus making a very good, if primitive, bellows. The forge is roofed with grass to protect the workers from the sun.

I have said elsewhere that, wherever possible, we bought our flour from the villagers, and the above photo, shows a supply of this precious commodity all ready to be carried away. A string of white beads, large enough to go over the head, was taken in exchange for about a pound of ground millet. The people here go almost entirely nude.

On the occasion of a marriage great rejoicing takes place among the villagers, the men and women, in separate parties, dancing round the village wall. Here we see the men clapping their hands, beating their feet on the ground, and chanting a monotonous song. They wear a goat-skin round their waist. Men in pairs leave the throng and dance forward, lifting their knees high up, throwing their heads back, and keeping their elbows well into their sides. Presently they dance back again, their places being taken by fresh warriors. Sometimes these men wear on their heads a pair of goat’s horns, fastened tightly into the hair. These horns, which appear to be sprouting out of the men’s heads, give them a decidedly diabolical appearance.

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 9-10

The natives from the surrounding villages used to come in with supplies to the town, where we had established our market ; and after selling their wares and emptying their baskets of flour, they would sit down under the trees for a friendly chat with their neighbours. I noticed on some of these people ivory armlets that had grown into the flesh, having been put on when the wearers were very young. Most of the flour bought here was made from bananas. The fruit is gathered while still green, peeled, and then split down the middle. The slices are placed in the sun, and, when thoroughly dry, are pounded into flour with a smooth stone on a rock. Banana flour has rather a bitter taste, and is very unpalatable to Europeans. It was eaten by the officers in small round baked cakes as an indifferent substitute for bread.

We spent Christmas Day at Mumia’s. In the fort it was, of course, observed as a holiday, and many of the native women came in and danced. They were dressed in pretty coloured pieces of cloth, which are here bartered by the Government for food.

The dance lasted many hours, and was not exhilarating. The leader of the dance carried an umbrella, and the ceremony was conducted on “follow-my-leader ” lines. The dance continued many hours, and as the fair ladies became hot they cooled themselves by the simple expedient of removing a garment or two. On the journey back to the coast a halt of several days was made on the shores of Lake Naivasha. This lake is of volcanic origin, and contains an island in the shape of a crescent moon, which is undoubtedly an old crater. A few prisoners are seen in the photo, engaged in cleaning up the camp at this remote spot.

Another snap-shot shows a magnificent pair of tusks bagged by Captain Ferguson. They weigh 108ib. and 110ib respectively. It speaks highly for the honesty of the natives that, several days after Ferguson had mortally wounded the elephant; they found it and immediately sent, messengers to tell him where the grand beast had died. Four men carried each tusk slung on a pole. On the right of the photo, we see Colonel Macdonald himself; and on the left is Captain Ferguson, who shot the elephant. The man in the centre is a Somali headman named Ali. He was with Count Teleki’s expe--dition which discovered Lakes Rudolf and Stephanie. He was never tired of talking of the hardships of that expedition, when for nine days the men were without food.

They managed, however, to subsist on nuts and the roots of trees. The above photo, shows some of the “ incorrigibles ” of the expedition—men who were repeatedly convicted of stealing food from their comrades. As a punishment, they were fastened together in the way shown in the photo. An iron collar is worn round the neck, and through a loop in this a chain is passed, fastened at the end by a padlock. The prisoners are compelled to carry a load in the usual way, but are guarded by a few soldiers. If this were not done they might seize their opportunity and smash the padlock. So salutary an effect, however, does this punishment have, that escaped prisoners have been known to bring their irons back and deposit them by stealth in the camp, lest at some future time they should be recaptured and accused of having stolen their fetters!

Our Adventures in Unknown Uganda. Part 10-10

The accompanying group of officers was taken by Mr. Stanley Tomkins, on the ss. Canara, during the voyage from Mombasa to Aden. Ten officers started with the expedition in 1897. A great loss was suffered in the death of Lieutenant N. A. Macdonald, 14th Sikhs, who was killed in one of the fights against the mutineers at Lubwa’s. His company of only partially trained Swahilis was suddenly attacked in thick grass, and while gallantly rallying his men, he was shot dead. Captain R. Kirkpatrick, D.S.O., Leinster Regiment, had seen much of the fighting in Uganda; he afterwards fell a victim to the treachery of a native tribe. With an escort of nine men, he had left his camp to climb a hill a few miles distant, as he was anxious to get a good view of the surrounding country. The natives appeared to be very friendly, and were walking with the small party. Suddenly they attacked Captain Kirkpatrick and his men with spears, and only two of the party succeeded in escaping and reaching camp. The loss of these two comrades, who were both deservedly popular, was most keenly felt.

Major Woodward, who was suffering from a sunstroke, had been invalided home a year before, and Lieutenant. Osborne had been severely wounded in the knee at the Battle of Kabagambi, and had also returned to England. He was much missed by the remainder of the officers. Captain Pereira, Coldstream Guards, who belonged to the Uganda Rifles, remained at Mumia’s.

Late 1800’s and the Lunatic line

Click below

Joseph Thomson and the Exploration of Africa

THROUGH KAVIRONDO TO VICTORIA NYANZA.

ON the 13th of December, 1882, having completed all necessary preliminary arrangements, I embarked on the B.I.S.N. Company’s steamer Navarino bound for the East, in which, by the generosity of that enterprising company, I received a free passage. Leaving the steamer at Suez, I enjoyed a run to Cairo, where I had the pleasure of associating with the members of the Geographical Society on the occasion of a farewell dinner to General Stone, who at that time was returning to his native country. Lieut. Weissman, on his way home after his brilliant march across the continent from west to east, was also at Cairo, recruiting his health in the balmy climate of Egypt, before facing the rigours of a German. winter. I had the further satisfaction of meeting with his celebrated countryman, Schweinfurth, from whom I received much kindly attention.

Continuing my way after a most agreeable trip, we touched as usual at that most impressive and picturesque of eastern ports, Aden, and then, after one of the quickest and most enjoyable passages on record, we neared, on the 26th of January, 1883, the now familiar island of Zanzibar.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_one.htm

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_two.htm

A FORTNIGHT IN A FOREST FASTNESS.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_three.htm

THROUGH THE DOOR OF THE MASAI.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_four.htm

PREPARATION FOR A NEW ATTEMPT.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_five.htm

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_six.htm

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_seven.htm

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_eight.htm

TO LAKE BARINGO Viâ MOUNT KENIA.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_nine.htm

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_ten.htm

THROUGH KAVIRONDO TO VICTORIA NYANZA.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_eleven.htm

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_twelve.htm

SPORT AT BARINGO AND JOURNEY COASTWARD.

http://www.geocities.ws/olmorijo/thomson_chapter_thirteen.htm

Joseph Thomson and the Exploration of Africa

“He who goes gently goes safely; he who goes safely goes far.”

Joseph Thomson led six expeditions into uncharted areas of Africa. He opened up new routes to Lake Nyasa and Victoria Nyanza, was the first white man to enter the Rift Valley, mapped huge expanses of what are now Kenya, Morocco and Nigeria, made important scientific discoveries about Lake Tanganyika, Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya and discovered Thomson’s Falls (named after his father) as well as new species of plants and animals, including Thomson’s Gazelle.

http://www.penpontheritage.co.uk/joseph-thomson/the-exploration-of-africa

Uganda Railways

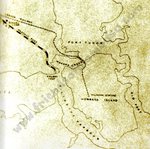

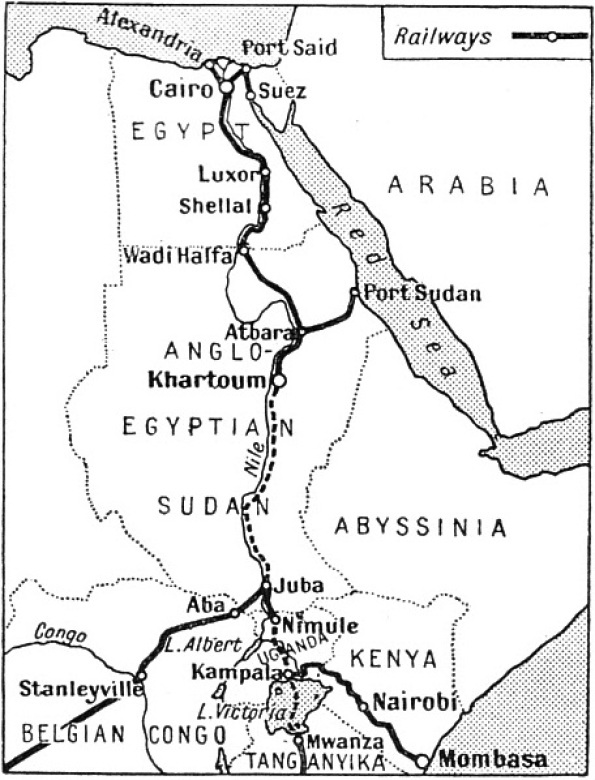

Above, an interesting historic map of 1892 that has several major historic points that are discussed to this day.

Schneppen’s assertion is based primarily on the terms of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty of 1 July 1890. In the Treaty, Germany and Great Britain agreed on several territorial interests.

Germany gave up its claim of Zanzibar Sultanate-which then stretched to what is today the Kenyan coast-in exchange for Heligoland and the coast of Dar es Salaam.

While the Heligoland treaty does not include any mention of a mountain, the demarcation lines do not seem to have changed around that part of the borderline. It seems more plausible that in giving

away its claim on Zanzibar and its entire Sultanate, which then included what is now the Kenyan Coast, the Germans acquired Kilimanjaro.

Heligoland is a small German archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were at one time Danish and later British possessions. The islands are located in the Heligoland Bight in the south eastern corner of the North Sea, and had a population of 1,127 at the end of 2016.Wikipedia

This map further illustrates the initial proposed rail route in 1891… Line of first Reconnaissance proposed by Sir Guilford Molesworth running parallel to Athi River from around Tsavo, also a typical straight line from Mombasa to Ugowe Bay (Lake Victoria) is also drawn.

“The route recommended for the projected railway as illustrated in (Permanent Way by M.F Hill) is practically that which Sir Guildfield Molesworth, in his report on the proposed railway, dated May 1st 1891, states’ present the only probable chance of obtaining an inexpensive railway’ . The main point of difference being that the valley of the Nzoia River is flowing down to the Lake Victoria instead of the Nyando River. Obligatory points on the proposed route Taru, Salt River, Kedong valley, Lake Victoria, the Guaso Ngishu Plateau and the Nzoia River Valley”.

Looking closer later on of that area during the surveying perspective, from Ugowe Bay, the surveyors marched in a north-west direction through South Kavirondo and entered Mumias on May

18th 1892, a dwelling-place named after a chief.

The survey team split in two, their primary object of finding a suitable harbour on the North shore of Victoria Nyanza brought them here in bringing the maps-to- date and second party remained in

Mumia’s.

It is also thought the fighting in Uganda was over and safe for caravans to cross the Nile. Earlier tensions had continued to flare throughout most of 1891 between the Catholics and the Protestants. Although the factions had agreed not to attack each other, a murder in Mengo sparked off a war that would change the balance of power.

The parties for Uganda and the lake left on May 21st and crossed into the Nzoia River below Mumias by means of the Berthon boats.

Since, Sir Guildfield Molesworth in his initial findings mentions and possibly esteemed this proposal as per, his quote “The main point of difference being that the valley of the Nzoia River is flowing down to the Lake Victoria instead of the Nyando River”. After detailed surveying was carried out ,It was now established that Ugowe Bay (Port Florence) now called Kisumu would take precedents over the initial proposal.

Kenya Uganda Railways

Since the British were already established in India and had been there for over a century or so, they already had many Indian artisans available in many capacities working under the British and to add further, also looking closely at many influential factors in the big decision making also came the Suez Canal and the big question in the Nile’s Source was a factor in sourcing 1860-3 (Speke and Grant) and building up on that. Most of the Imperialistic influents in many positions were already involved in many aspects of trade and many other Colonial administrations thus the need for Suez Canal for an essential shorter route through from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and into the Indian Ocean was most important. Most if not all influential Colonial Military personal and ranked of the British Army came from British India during the late 1800, early 1900’s and this was the case also during the WW1 campaigns in Eastern and Northern Africa. The Muslim Punjabi and Sikh soldiers were stationed along the East Coast in the late 1800’s.

Sir William Mackinnon who had very strong influential connections with British India through his large shipping business, also owned one of four chartered company “The Imperial British East Africa company” chartered in 1888 (first East African British currency is also dated 1888), the only private initiative authorized by Great Britain to work in East Africa. The building of Uganda Railways needed some mixture of labour force and also skilled personal; the initial thoughts was to get the Chinese workers involved, but the British later opted for Indians mainly from the Punjab and Goa.

The total recruitment campaign of Gujarati’s and Punjabis was handed over to a Mr Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee who had set up recruitment spots along the West Coast and Punjab (remembering there was no Pakistan). Supposedly this would also make communication amongst each other easier as East Africa for the Colonial British Empire was in its infancy. The British were also under a lot of pressure too, they had to rush to get to the source of the Nile before any other European Nations did and inevitably the British feared France the most as they had already occupied Obock in Somalia land (acquiring 1862) and not because of Germany as many would have initially thought, all this came about and was a challenging movement for the Europeans called “The scramble for Africa”.

Over 2,500 workers died while laying the Kenyan- Uganda railways that is approximately four workers per mile of track, high number of those killed were from mostly the Indian sub-continent who had left their country and come to work on foreign land on contract basis. It is about time they got some deserving recognition, here is the legacy they left behind:

In 1910 Sir John Kirk remarked on the work of Indian Traders in Nairobi:

In fact drive away the Indians and you may as well shut up the Protectorate. It is only by means of the Indian Trader that articles of European use can be obtained at moderate prices.

Winston Churchill in “My African Journey”: It is by Indian labour that the one vital railway on which everything else depends was constructed.

Nearly all the workers involved on the construction of the Uganda railway line came from British India. An agent was appointed in Karachi responsible for recruiting the workers, artisans and subordinate officers and a branch office was located in Lahore, the principal recruiting centre. Workers were sourced from villages in the Punjab and sent to Karachi on specially chartered steamers belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Shortly after recruitment began, a plague broke out in India, seriously delaying the advancement of the railway. The Government of India only permitted recruitment and emigration to resume on the creation of a quarantine camp at Budapore, financed by the Uganda Railway, and where recruits were required to spend fourteen days in quarantine before departure.

A total of 35,729 labourers and artisans were recruited along with 1,082 subordinate officers, totalling 36,811 persons. Each worker signed a contract for three years at twelve rupees per month with free rations and return passage to their place of enlistment. They received half-pay when in hospital and free medical attendance.

Recruitment continued between December 1895 and March 1901, and the first coolies began to return to India after their contracts ended in 1899. 2,493 workers died during the construction of the railway between 1895 and 1903 at a rate of 357 annually. While most of the surviving Indians returned home, 6,724 decided to remain after the line's completion, creating a community of Indians in East Africa

The Planning and the Construction of Ugandan Railways

http://www.pubs-newcomen.com/tfiles/74ap045s.pdf

The Lunatic Express – A photo essay on the Uganda railway.

http://www.tesocollegealoet.sc.ug/dev3/the-lunatic-express/

The main reason why most of the railway workers came from India was that no other country would provide so vast and competent a group of engineers, artisans and

labourers who were already well accustomed to the tropical conditions.

Recruitment continued between December 1895 and March 1901, a total of 35,729 including labourers, artisans and others were recruited along with 1,082 subordinate

officers, totalling 36,811 persons.

Shortly after recruitment began, a plague broke out in India, seriously delaying the advancement of the railway.

The Government of India only permitted recruitment and emigration to resume on the creation of a quarantine camp at Budapore, financed by the Uganda Railway, and

where recruits were required to spend fourteen days in quarantine before departure.

It is thought that Dhows that were the norm form of transportation in crossing the Oceans during that time/period, were now used, they held safer smaller numbers,

which would help during this drip feed recruitment process, thus easing the large influx of number of people that were urgently required to cross the Indian Ocean.

They came in ships and dhows, having been coaxed here to build one of the continent’s great railways.

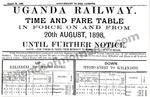

Uganda Railways 2oth Aug 1898 (Time and Fare Table)

Uganda Railways

2oth Aug 1898 (Time and Fare Table)

Although the Uganda Railways never reached Uganda as such in today’s term, why was it that it was called “Uganda Railways”,well, that is for some other day!

Below is fascinating details to the initial commissioning of the Uganda Railways, as it was called “Up and Down” “Up” meant Kilindini to Mtoto-Andei and “Down” meant Mtoto-Andei to Kilindini, in a

step forward that in fact entailed, change of land scape, transport method, new places springing up, postal services coming into its fruition, the by-laws, transporting of live stock….etc

PASSENGER’S LUGGAGE:—Passenger’s luggage will be weighed and the following quantities allowed free of charge viz.—First Class, 56 ‘pounds, 2nd Class, 28 pounds, and 3rd Class, 14

pounds, and half these quantities for each child’s half ticket.

Luggage in excess of the above quantities will be charged per cwt. as follows, riz :—One to 25 miles, Rs. 1-8 ; 25to 50 miles, Rs 3; 50 to 100 miles, Rs.6 ; subject to a minimum of eight

annas.

The following is the basis of calculation of freight on luggage in excess of free allowance, viz.—1 to 14 lbs.; 15 to 28 lbs., as 28 lb ; 29 to 42 lb., as 32 lbs.; 43 to 56 lbs., 57 to 70

lbs. as 70 lbs., 71 to 84, lbs ; as 84 lbs., and 85 to 98 as 98 lbs.; and 98 to 112. as 112lbs.

Only small packages which can be placed under the seats, will be allowed to be taken into the carriage, as over- crowding a carriage with luggage is likely to put other passengers to

inconvenience.

The free allowance can be claimed only when luggage is booked before the journey is commenced. If luggage is not booked before commencement of the journey it will be charged at destination

or en- route on the full weight carried and no free allowance will be made. All luggage must be legibly marked and addressed in English.

Any luggage not plainly addressed or properly secured will be carried at owner’s risk. The Railway will not be responsible for any loss or damage that may occur to luggage taken free of

charge whether carried in carriages or Brake Vans.

As a convenience to the public, Luggage and Goods may be booked through by Goods Train to and from Kibwezi mile 193, but arrangements must be made to take delivery immediately on arrival

of each consignment at Kibwezi and the Railway will not be responsible for undelivered Goods at Rail-head Station. The Goods and Luggage rates for stations beyond Mtoto Andei may be ascertained from

the Station Masters.

LIVE STOCK Live Stock will be carried on Mixed Trains provided only there is room on the train, and in all cases at owner’s risk ; the loading and unloading must be arranged for by the

owner.

Dogs are to be carried in dog boxes of Mixed Train’s only and must not be taken in to the carriage.

PUNCT ITAIJITTY OF TRAINS:—The times shown in this Time Table are those at which the trains are intended to arrive at and depart from the several stations. The Railway does not guarantee

punctuality, but every endeavour will be mode to ensure it.

TELEGRAMS -“Urgent” and “Ordinary” Private Telegrams will be accepted at any of the above Stations, and also at the following offices up to and beyond Rail-head, viz:—Darajani mile 173,

Masongaleni, mile 182, Kibwezi mile 193, Kiboko mile 217, Mnani mile 242, Kiu, mile 258, Leucania mile 283, and Nyrobie, mile 307.

ombasa Post Office is also connected with the Railway wire, and telegrams interchanged with this Office and Railway offices arc charged six annas extra. The charges are for “Urgent” telegrams, Rs. 2,

for the first eight words or groups of five figures, and annas four for each additional word or group of five figures; for “Ordinary” telegrams half the above rates.

BYE-LAWS Tho Uganda Railway Bye-laws are posted at all stations.

By Order of the Chief Engineer,

TRAFFIC MANAGER’S OFFICE: A. E. CRUICKSHANK,

Traffic Manager

Traffic Manager’s office :

Kilindini, 15th August, 1898.

The railway was opened to Voi for goods on 15

December 1897 and to passengers on 1 February 1898. The first telegram to be received at Voi by Uganda Railway Telegraphs arrived on 18 November 1897, so the telegraph and probably Railhead were this

far at that date. But most of the rolling stock was already commandeered for use of the forces proceeding via Railhead at Ndii to Uganda to quell the Sudanese mutiny, and any regular service was

subject to the demands of the military.

The earliest complete timetable that seems to

have survived relates to the opening of the passenger service to Mtito Andei on 20 August 1898, when Railhead moved up to Makindu. There is no mention of mail- carrying, but an interesting foot-note

adds "Telegraph offices exist right up to and beyond Nyrobie.” We know that on 8th December 1898 Railhead was at 242 mile, when a special train took H.H. the Sultan of Zanzibar to

inspect the transport camp.

In May 1899 Railhead was moved forward to a

swampy area called after a stream (in various spellings) Nairobi. The railway station was opened for goods on 17 July, on which day the head-quarters staff arrived from Kilindini; Railhead had been

told by telegram to advance a further 9 miles to make room.

The station opened to passengers on 15 August, Hall notes on that very day that it lay ”8 m. away by trolley” from Fort Smith. It is confirmed by Scottish Mission Records (Kikuyu) that by 18 July

Railhead was situated "a mile from Kikuyu” and that the P.O. had closed at Fort Smith. From the same source we know that by 16 September the Missionaries were having to collect their mail "from

Nairobi”, though according to the usually well researched Hardy, Railhead did not move to Escarpment till 2nd October.

On 17 October 1899 Hall states that the railway

station is Im. from Fort Smith, Kikuyu and was opened to goods traffic on 1 October. He adds he was "up at Rail-head about 15m. from here” (only half-way to Escarpment?). Hall was "ousted” from

Kikuyu, and Fort Smith to be evacuated by 26 November when Hall was already at Machakos, "23m. from the railway”. Ainsworth had moved his provincial H.Q. from Machakos into Nairobi, but on what exact

date is not certain.

Trains now ran through the night, speeding a

service to Nairobi. Indeed the G.P.O. Mombasa was able to announce simultaneously the fortnightly mail service to the limit of EA Protectorate responsibility at Eldoma Ravine took 10 days in 1896,

had taken it took 20 days. In actual fact there were few trains in February, March or April,as the line was washed away by floods.

On 21st May 1900, T.E.C. Remington is reported in the Gazette as leaving Mombasa to open post offices up-country and his return is chronicled for 9 June.

The railway extension from Kilindini into Mombasa was opened for traffic on 20 June. Trains (Tuesday and Friday from Mombasa) would leave at 11.15 to fit into the existing timetable. Above the announcement in the E.A. Gazette was a postal notice, "a list of all Post Offices established along the Uganda Rly", which reads:

Kilindini Makindu

Voi Nairobi

Kibwezi Railhead (Escarpment)

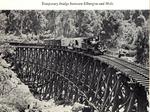

The Escarpment cable inclines started to work

in May 1900 (having been greatly delayed by the effect of the South African war on the availability of steel) and Railhead was taken to the floor of the Kedong Valley soon

after.

The railway was opened to goods traffic, using the rope inclines as far as Naivasha on 15 August 1900 with intermediate stations at Kedong (mile 364), i.e. Escarpment (the Mombasa extension accounts for the extra two miles) and Longonot (mile 374).

A rail camp seems to have remained on the

Kedong River at the foot of the Escarpment, since it was a major problem to replace the rope inclines, which were in use for 20 months by the permanent line to Rift bottom, rather than track-laying

forward over flat ground.

On 15 September 1900 a Postal Notice printed in

the Gazette reports: 'A temporary post office has been opened at Kiu, and the Kedong post office has been removed to the Escarpment". A more permanent P.O. was opened at Kedong (Escarpment) station

on top of the Rift, moving up from the Kedong river. Railhead Camp moved on to Gilgil in July, to Eburru in August and is recorded as being at Nakuru on 15 October 1900.

The Escarpment rope inclines were eventually

superseded on 4 November 1901 by a permanent line down the slope, Kedong station was then closed and a station opened at Kijabe on the permanent line ( a post office was not placed at Kijabe until

1903).

But this is to anticipate. No passenger

extensions were made beyond Escarpment in 1900, but a change was made in the timings of the trains w.e.f. 1 November 1900. The new timetable printed in brief, reduces the "Down" time from Nairobi to

Mombasa to under 24 hours.

UP TRAINS DOWN TRAINS

Mombasa dep.11.40 Escarpment dep 15.20

Kilindini arr. 11.48 Nairobi arr. 17.50

dep. 12.00 dep.10.00

Voi arr. 18.40 Makindu arr.18.15

dep. 19.40 dep.19.00

Makindu arr. 4.30 Voi arr. 2.00

dep. 5.30 dep. 2.30

Nairobi arr. 15.30 Kilindini arr. 9.30

dep. 9.00 dep. 9.40

Escarpment arr. 13.30 Mombasa arr. 9.08

NOTE: The "UP" trains will leave Mombasa on Tuesdays and Fridays and "Down" trains will leave Nairobi on Sundays and Thursdays only. Between Nairobi and Escarpment the Mixed train will run each way on Wednesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays.

In 1907 Winston Churchill noted that problems arising from the impact of European and African involved also a third race, the Asiatic. The industry, thrift and sharp business acumen of the Indian} combined with his ability to live on a few shillings a month, would give him economic superiority if unchecked. After discussion of the problem Churchill put the case of the British Indian.

Churchill.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [67.1 KB]

Kenya – Uganda Railway: A short history

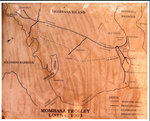

The first operational railway in East Africa was a two foot gauge trolley line in the port of Mombasa operated by hand propelled wagons, the original route being supplemented with track recovered from the abortive Central African Railway which had reached a mere 11 kms inland from Mombasa Island.

By 1896 all was ready for a second attempt to build a railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria and the inaugural platelaying ceremony was performed on 30th May, 1896. However the German East African railway had already commenced construction of the line from Tanga in May 1893, but after taking two years to build 40kms of line, the Usumbara Bahn was declared bankrupt and construction had to be taken over by the German Government. The line eventually reaching Moshi in 1912.

http://www.greywall.demon.co.uk/rail/Kenya/nrm.html

1896 - 1926: Uganda Railways

The Railway in East Africa began as Uganda Railways, dating back to as early as 1896 when the first railway line was laid down in Mombasa. Undertaken by the British Colonial government, the intention

was to get the railway line to landlocked Uganda, one of its protectorates. The main reason behind the project was to exploit its resources and protect the source of the river Nile a life line of

Egypt, a British sphere of Influence. The construction of the railway line started in 1896 and was completed in 1926.

Pay day on the Railway. The minimum wage was set at 15 rupees, approx. $US 50.50 per month, regardless of productivity.

Construction of the Kenya-Uganda Railway

http://www.enzimuseum.org/archives/275

Disassembled ferries were shipped from Scotland by sea to Mombasa and then by rail to Kisumu where they were reassembled and provided a service to Port Bell and, later, other ports on Lake Victoria (see section below). A 7 miles (11 km) rail line between Port Bell and Kampala was the final link in the chain providing efficient transport between the Ugandan capital and the open sea at Mombasa, more than 900 miles (1,400 km) away.

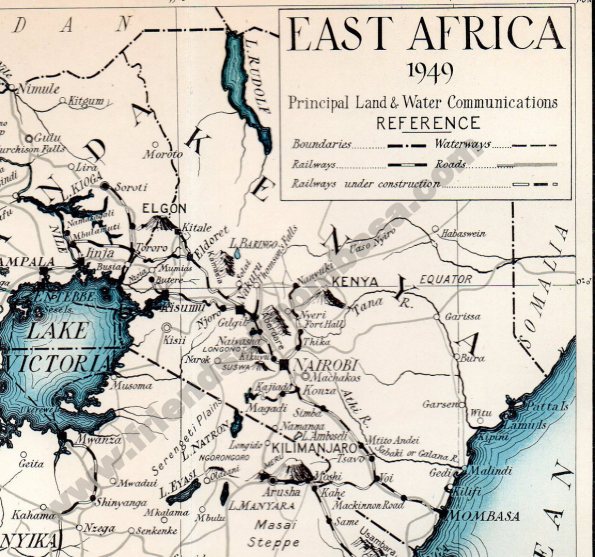

Branch lines were built to Thika in 1913, Lake Magadi in 1915, Kitale in 1926, Naro Moro in 1927 and from Tororo to Soroti in 1929. In 1929 the Uganda Railway became Kenya and Uganda Railways and Harbours (KURH), which in 1931 completed a branch line to Mount Kenya and extended the main line from Nakuru to Kampala in Uganda. In 1948 KURH became part of the East African Railways Corporation, which added the line from Kampala to Kasese in western Uganda in 1956.[19] and extended to it to Arua near the border with Zaire in 1964.

The focusing effect of railway junctions and depots created many of the interior's modern towns and ports, such as:

- Eldoret, originally called "64" after its distance, in miles, from the railhead at the time

- Jinja, a city and port close to the outlet of Lake Victoria, the source of the River Nile

- Kisumu, a city and port on Lake Victoria allowing ferry transport between Kenya, Tanganyika (modern Tanzania) and Uganda

- Kitale, a small farming community in the foothills of Mount Elgon

- Nairobi, started as a rail depot, becoming the capital of Kenya.

- Nakuru, where the main line splits, one branch going to Kisumu and the other to Uganda

- Port Bell, a rail-linked port, near to Kampala, on Lake Victoria allowing ferry transport between Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uganda_Railway

1927 – 1948: Kenya-Uganda Railways & Harbours

In 1927 the name changed from Uganda Railways to Kenya-Uganda Railways. In the same year, "harbours" was added after the administration of the harbours was combined with that of the railways and the

name became Kenya-Uganda Railways & Harbours. The railway system in Kenya & Uganda operated together until 1948.

1948 – 1966 East African Railways & Harbours

In 1948, the name changed to East African Railways & Harbours. This was because Kenya, Uganda & Tanzania were now under the same British Colonial Administration. Following the terms of the

Versailles Treaty in 1919 Germany lost all her colonies worldwide. The colonies became the mandate territories of the League of Nations (currently United Nations). Victorious nations surrounding the

mandate territories were allowed to administer them on behalf of the League of Nations.

1966 – 1969 – East African Railways Corporation

Following independence, the three East African Presidents Jomo Kenyatta, Julius Nyerere and Milton Obote met in Arusha and came up with the Arusha declaration in 1966. In the declaration, it was

resolved that efficiency in parastatals needed to be improved. One of the parastatals identified for reform was East African Railways & Harbours. It was decided in this meeting that harbours be

divorced from the railways administration. This was done purely for the purpose of efficiency. In 1969, the name changed to East African Railways Corporation.

1969 – 1978 – Kenya Railways Corporation

By 1978, the distrust between the three East African leaders Nyerere, Kenyatta and Idi Amin had reached fever pitch. This was partly due to the different political ideologies that the three leaders

practiced. Additionally, Nyerere and Amin believed that Kenya was benefiting more from the East African Community than Tanzania and Uganda. Personal differences between the three leaders culminated

in the break-up of the East African Community in 1977. The break up led to the birth of Kenya Railways, Uganda Railways & Tanzania Railways as separate entities.

2006 – To-date – Rift Valley Railways

Rift Valley Railways (RVR) took over the operations of the Kenya and Uganda Railways on 1st November, 2006. RVR was established on October 14, 2005, when the Government of Kenya and the Government of

Uganda jointly tendered through a bidding process, a 25 year concession for the rehabilitation, operation and maintenance of the railways then run by Kenya Railways Corporation (KRC) and Uganda

Railways Corporation (URC) respectively.

More: http://www.riftvalleyrail.com/content-layouts

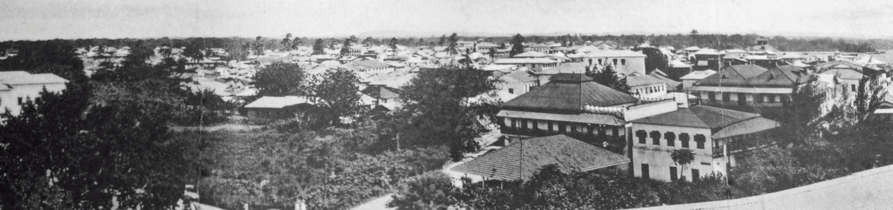

The Kenya – Uganda Railway was built by the Imperial British East Africa company back in the 1890s. Construction of the line began at the Kilindini Harbour in Mombasa in 1895. Around 1900, the line arrived at the present site of the city of Nairobi. Indeed, Nairobi owes its existence to railway engineers who drained a vast swamp, thus enabing the construction of permanent buildings. Indian labourers began commercial activities to cater for railway crews and colonial administrators. The railway arrived at Port Florence (Kisumu) around 1901.

Eventually, the British Government took over the territories of Kenya and Uganda from the Imperial British East Africa Company. In 1920, Kenya became a colony of the Crown under direct administration of the Colonial Office in London.

The railway was expanded from Eldoret to Kampala, bypassing the use of ships on Lake Victoria from Kisumu. Additional branch lines were built from Nakuru to Nyahururu, from Nakuru to Rongai and from Konza to Magadi. The invasion of Ethiopia by Italy during World War 2 forced the British to build a railway from Nairobi to Nanyuki in order to supply its forces. British troops forced the Italians out of Ethiopia and restored Emperor Haile Selassie to his throne.

After independence in the early 1960s, railway and port operations in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania were administered by a single body: the East African Railways and Harbours. The break up of the East African Community in 1977 marked the beginning of the end for the region’s railway system. Each of the three East African countries took up running its own system. In Kenya, railway and port operations were split between two state-owned corporations: Kenya Railways and Kenya Ports Authority. The railway became starved of funds.

In Uganda, civil war between 1979 and 1986 paralyzed railway transport which is yet to recover to this day.

More on Kenya-Uganda Railways: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uganda_Railway

Sikh Heritage: http://www.sikh-heritage.co.uk/heritage/sikhhert%20EAfrica/sikhsEAfrica.htm

http://www.greywall.demon.co.uk/rail/Kenya/nrm.html

http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/eastafricanrailways/indexEAR.htm

Nairobi-Mombasa train with Kenya Railways, Nairobi airport transfers to railway station Rift Valley Railways.Train safari journeys from nairobi to mombasa to Nairobi african great train travel and tours. Book your Train travel in Kenya from Nairobi - Mombasa, operated by Rift Valley Railways

http://www.eastafricashuttles.com/train.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenya_Railways_Corporation

The Lunatic Line

http://theeye.co.ug/lunatic-express-potted-history-uganda-railway/

Weston Langford Railway Photography

Documenting railways and related infrastructure since 1960

http://www.westonlangford.com/images/photo/page/644/

The Indian migrants who built Kenya's 'lunatic line'

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/12/11/world/africa/kenya-railways-india/

How many people did the man-eating lions of Tsavo actually eat?

http://www.siteadvisor.com/restricted.html?domain=http:

Mike’s Railway History

http://mikes.railhistory.railfan.net/r061.html

Mile 581, 19th Dec 1901 reached the shores of Ugowe Bay (Lake Victoria). That is Florence Preston's wife, the foreman plater at the railhead Roland Preston drove home the final

key of the railway.

Port Florence (Kisumu) was named after Chief Engineer Mr Whitehouse's wife, but it was Ronald’s wife Florence Preston who was photographed ‘driving the last spike’ on the shore of Lake

Victoria.

Port Florence had been renamed Kisumu (a name derived from the Luo word ‘sumo’ meaning the place of barter trade).

The railway line was finished in December 1901 as the sun was making its descent on the town of Kisumu. To commemorate the end of construction, Mrs. Ronald Preston, wife of the plate laying engineer, drove the final steel key into the rail.

In an interesting twist, the chief engineer’s wife Mrs. Whitehouse and Mrs. Preston had identical first names, Florence. “Port Florence was named after the Chief Engineer’s wife Florence Whitehouse, but it was Ronald’s wife Florence Preston who was photographed ‘driving the last spike’ on the shore of Lake Victoria…” Preston himself inscribed in his book, Oriental Nairobi. Because of the photo, most accounts say the town was named after Mrs. Preston.

The confusion was later resolved when the name was changed to Kisumu – Port Florence was found, somewhat inconsiderately, unworthy of the locale by Special Commissioner of Uganda, Sir Harry Johnson. In a letter, he succinctly wrote “If the native name of the place be laid aside, the European name to be chosen should be of some member of the British royal family or of some great explorer associated with the discovery of Lake Victoria, Nyanza.

” All told, it took five years to complete the railway line and it would take another three decades before it was completely extended to Kampala. And while that seems like a long time – consider that the American Transcontinental Railroad took just six years – what’s truly impressive about East Africa’s line is that it wasn’t building just a railway.

Uganda Railways

Although called Uganda Railways, there was no railway line as such from Kenya to Uganda,1896-to Dec-1901 Mombasa-Kisumu (Fort Florence) 581 miles covered nearly 2800 mainly Indians died/killed. Disassembled ferries were shipped from Scotland by sea to Mombasa and then by rail to Kisumu where they were reassembled and provided a service to Port Bell and, later, other ports (Entebbe) on Lake Victoria. A 7 miles (11 km) rail line between Port Bell and Kampala was the final link in the chain providing efficient transport between the Ugandan capital and the open sea at Mombasa, more than 900 miles (1,400 km) away. Cont.......

Kisumu..Kavirondo

Early in the 1820s David Napier conceived the grand notion of the Firth of Clyde 'Watering-places' which, for more than a century, were to occupy a special affection in the hearts of Scots in general

and Clydesiders in particular, and the nostalgia of the trips 'doon the watter' lingers on. At this time Napier was the acknowledged genius of the steamship constructors but was frustrated by the

reluctance of sailing ship owners and operators to change, and by the temerity of potential passengers. He had already resorted to ownership of vessels which he had equipped with his steam engines

and set up a steam packet service between the Clyde and Ulster.

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/nyanzawateringplace.htm

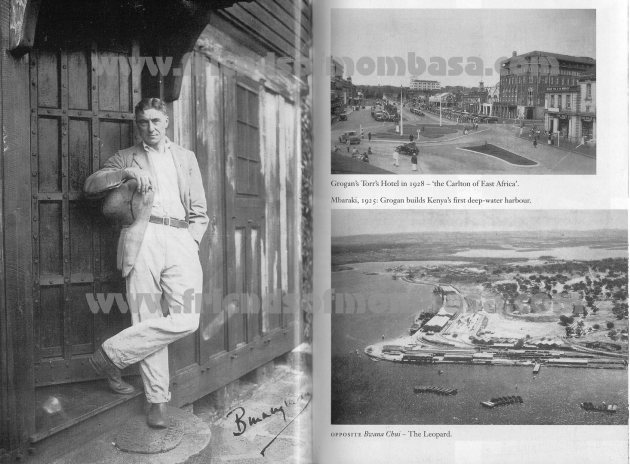

Colonel Ewart S. Grogan

Steam to Mombasa - English • Great Railways

East African Railways and Harbours Corporation

East African Railways and Harbours

Kampala to Nairobi

The Mail Train ran three times a week between Nairobi and Kampala and conveyed first and second class accommodation only. Many parents living in Uganda in the 1950s and early 60s sent their children to school in Kenya and School Trains ran between Kampala and Nairobi/Eldoret at the start and end of each 12 week term. There were separate trains for secondary school boys and girls, but boys and girls attending primary school were conveyed on the same train. Sometimes a secondary girls' train would have coaches attached for primary school pupils travelling to the Hill School in

Eldoret where the train arrived from Kampala in the dark at 0530. The journey from Kampala to Eldoret took about twelve hours and that to Nairobi took about twenty four after the completion of the Busembatia to Jinja direct line in 1961. This line cut two hours off the journey and trains no longer called at Mbulamuti (for Namasagali) after which primary kids used to be sent to bed under the eagle eye of the lady escorts.

Please note: As far as possible the photographs appear in sequence Kampala to Nairobi, but the trains may be travelling in either direction.

More: http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/eastafricanrailways/KampalaNairobi.htm

http://mccrow.org.uk/EastAfrica/EastAfricanRailways/KURandH.htm

Images:

Images of old East African Railways and Harbours

http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/EastAfricanRailways/EARIainMulligan/IainMulliganEAR.htm

EASTAFRICANRAILWAYS & HARBOURSSTAFFMAGAZINES

AND SPEAR

June 1952 to December 1969

(all in PDF format)

“It is not uncommon for a country to create a railway, but it is uncommon for a railway to create a country.”

—Sir Charles Eliot, Commissioner of British East Africa in 1900-1904

http://www.energeticproductions.com/EARandH/index.htm

The Project Gutenberg eBook, In Africa, by John T. McCutcheon

Indian Punjabis recruited for the building of Railways

The story of Mr.Shams ud Deen

On 24th January 1896, the first group of 360 Indian workers arrived in Mombasa to begin the construction of the Uganda railway. Mr Shams ud Deen was one of them and this is his story written by his grandson Mr.Khalid Malik.

SAVETHE RAILWAY

TROLLEY

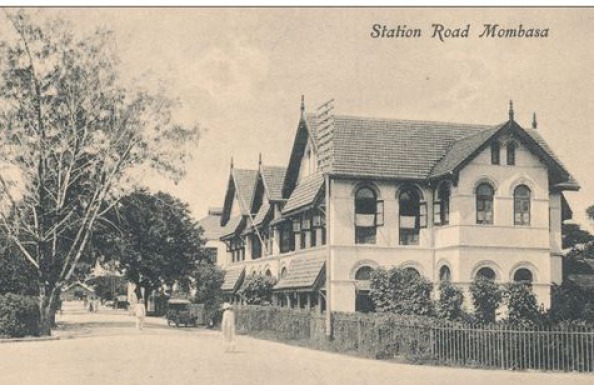

The photo above, to many that is captioned “Station Road” just does not register where this location was, but those who have lived in beautiful Mombasa will also know that in reality, this building is no-where near todays so called “Station road”, but in fact it is sited near Treasury Square (Old town area) and presume it refers to the old trolley rail.

The trolley track, ran on from Mbarak Hinawy Road (Vasco da Gama street) to Government Square (Customs area, Leven House) and on to Nkrumah Road (Mcdonald Terraces) past the Old Law Court on to Kilindini. Once famous and important building called “the Jubilee Hall” put up to commemorate the English Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897 and also used as a meeting place for Old Town elders until 1950’s and the track also veered to the right went to the famous Mombasa Club which was built in 1897 by the trader named Rex Boustead.

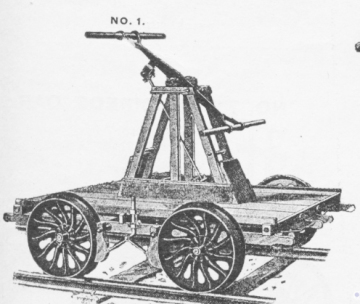

TROLLEYS

Between 1890 and the early 1920s, Mombasa island was served by an unusual transport system. A light two-foot gauge railway line was laid across the island from Government Square (in the old port) to Kilindini docks, and on it were pushed by hand small trolleys which could carry goods or passengers. By 1903 a branch had been laid to the station (then in Treasury Square), the hospital, the sub-commissioner’s house, the lighthouse at Ras Serani, the sports club and to the cemetery.

In 1900 it cost 4 annas to travel from Government Square to Kilindini, or

2 annas as far as the station. If two trolleys met on a single line, the lower ranking officer or civilian had to have his trolley lifted from the rails to allow his senior to pass.

Trolleys were withdrawn in about 1923, after which people had the choice of walking, hiring a rickshaw or taking a motor car. The first car arrived in Kenya in about 1900. A horse and carriage was a rare phenomenon, horses being very susceptible to local diseases, but can be seen in one or two early photographs.

Today, a replica trolley stands in the courtyard of Fort Jesus, on some reconstructed original line.

Mombasa, Kenya – A very early tramway?

https://rogerfarnworth.com/2018/05/21/mombasa-kenya-a-very-early-tramway/

Central African Railway , Mombasa

Although the usual method of travel was by hand-propelled trolleys, the Company anticipated heavier traffic and imported a 2ft gauge 0-4-2 locomotive built by Falcons of Loughborough and supplied by Ker and Stewart, named “Mombasa”. There were also some wagons, but details of rolling stocks are unknown, apparently the only reference to a train being a jocular note by Sir Fredrick Jackson in 1893.

https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Falcon_Engine_and_Car_Works

So what is the connection and so significance between a trolley line on Mombasa Island, running from the Old Port, where the Arab dhows anchored, to various Government buildings and Kilindini Harbour & CAR (Central African Railway)?

Sir William Mackinnon, the ship owner in charge of the IBEA, lost no time in writing to Lord Salisbury, six months after the signing of the Brussels Treaty,

suggesting Government assistance for the construction of a 60-mile (96.5 kms) railway inland from Mombasa. He also sought aid for opening up roads and forming "stations" along the route to Lake

Victoria.

As a result of this successful appeal, the Director of the IBEA in London was able to send out sufficient materials and rolling stock for building a narrow

gauge light railway to cost £50,000. The following year construction got under-way, starting from a point on the mainland opposite Mombasa Island, at the head of what has now become Kilindini

Harbour.

It was given the very ambitious title of the "CENTRAL AFRICA RAILWAY”, and as a symbol of the good intentions of the IBEA to open up the hinterland, sounded

very impressive. However the venture got no further than seven miles (11.2 kms) before work stopped. Although it covered no more than a tiny fraction of the distance to Lake Victoria and the source

of the Nile, the "Central Africa Railway" did secure a place for itself in history as one of the FIRST RAILWAY to be built in East Africa, albeit no wider than two feet (61 cms) gauge.