Foreword and Acknowledgements

This is a book about the more hidden aspects of immigration control, a topic that has received much publicity in recent years. We tell a story that we hope our readers will find disturbing because it is a story of unnecessary human suffering. The suffering has developed - with a kind of grim inevitability - from a loss of moral courage on the part of politicians, which has resulted in political acts of a kind that lay waste the lives of ordinary men and women. We try to show that what happens to these victims has implications for all of us because principles and procedures are adopted which can be extended to all sections of society with a considerable, but not always obvious, erosion of rights.

It is distressing to need to write this book at all. We have protest movements on behalf of Soviet Jewry and political detainees in South Africa, and such movements are needed. But the public seem to know and care nothing for the fate of abused British and Commonwealth citizens.

I have carried out research and written on race relations for ten years and the book results mainly from my desire to confront the public with what many of us have known for a long time. The public’s gaze is often averted, but I hope that this book, with others now appearing, will prevent people from saying that they never knew what was happening in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s. The research on which this is largely based was carried out in the summer of 1974. I would like to thank the many people who helped me, especially Vishnu Sharma and Mary Dines of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, and Lord Avebury. The University of Aberdeen gave

me a small grant for the research, for which I am very grateful.

Tina Wallace was a student in Uganda from 1969 to 1972. During the expulsion of the Ugandan Asians she was well known for her efforts on behalf of the Asians, working with a small group of expatriates in the Co-ordinating Committee for the Welfare of Asians. In 1974 the United Kingdom Immigration Advisory Service asked her to carry out a survey in Kenya and write a report on the situation of the Asians in East Africa. Some of this material is used here. We would like to thank the UKIAS, Barrow Cadbury Fund Ltd. and the Asian communities who made financial contributions, for affording Dr Wallace the opportunity to collect the material. The National Christian Council of Kenya, the Hindu Council, Mrs Stevens and many other individuals helped her in carrying out the study.

Chapter 2 was written by Dr Wallace and I must take major responsibility for chapters 1 and 3-6. The whole work is a collaborative effort, however, and the final product results from each of us working on the whole. Our collaboration was conducted largely over the telephone and in railway stations and cafes. This mode of work generated a lot of typing and the retyping of battered drafts; for this part of the work we would like to thank Anne and Beverley.

We have been helped by many people but the book is our own work and should not be taken as representing the views of any organisation, nor the views of the individuals who helped

us.

Robert Moore Aberdeen, Christmas 1974

The Lost Indians of Kenya

The Lost Indians of Kenya, New York City

The Lost Indians of Kenya

To the Editors:

Early in 1969, Gordhandass Shah, a resident of Kenya for thirty-five years and holder of a British passport, was told by the government that under its new Immigration Act he was no longer able to continue working in Kenya, and that he should leave the country within three months. Being a British citizen, he contacted the British Embassy to make arrangements for moving to England. He discovered at the Embassy, however, that because he was not a white British citizen, there were severe restrictions on his right to enter Britain, and that in fact it would not be possible for him to go there in the foreseeable future.

When the three months the Kenya government had allowed Mr. Shah were up, he was arrested and tried in Criminal Court for being in Kenya illegally. His argument that the country of his citizenship, the only country he was eligible to go to, would not admit him was found unacceptable, and he was jailed, later to be deported to England.

By all counts, Gordhandass Shah is one of the luckier of the more than 200,000 East African Indians who hold British passports. Police escort for the journey to England notwithstanding, he was able at least to find a home and earn his livelihood. For the other thousands it is a much more painful story: they are unable to earn a living in Kenya, and they are not being deported to England, where they legally belong.

The Indian’s troubles started in the early 1960s. In the preceding seventy years, more than a quarter-million of them had been encouraged by Britain to settle in the East African colonies. Most of these Indians were traders, artisans, or lower professionals, occupying the middle position between black and white in the colonial hierarchy. They lived in their own large communities, segregated from both the Africans and the English. They were the essential instrument of British rule over the indigenous population, and had greater contact with the Africans than did the British. As such, they received more privilege than was granted the Africans, but by the same token they earned a lot more of the black resentment than the colonists did.

When Kenya received independence in 1963, the Indians were offered the choice of obtaining either British or Kenyan citizenship. Because the painful, post-independence experience of the Congo was still fresh then, and because many Indians felt that the growing demand for position and power from the newly educated African middle class would lead inevitably to their exclusion from the job market, only about 10 percent of the Indian population applied for Kenyan citizenship. The rest chose what later turned out to be “devalued” British passports.

The current crisis began in 1968, when Kenya passed the first of its many laws that largely bar Indians with British passports from holding gainful employment. Almost simultaneously, the Labour government in Britain, expecting an influx of its colored citizens from the East African countries, limited to 1,500 the number of Indian families with British passports who could enter England annually.

As a consequence, there are now thousands of Indians in Kenya, unable to work there and denied the right to their legal homeland. As Nasir Butt, a father of seven who lost his job as an auto mechanic in 1968, said: “If we were victims of a natural disaster or running away from a communist country, we would have aid and interest. But now no one is interested, no one cares. We are not even considered refugees.”

Most of these “refugees” are skilled in some craft or another, but now they can be seen walking the streets of Nairobi, Mombasa, and other cities; some have taken to begging, others live on charity, and many have moved in with those relatives and friends who can still make a living.

The more enterprising ones have tried by various means to publicize their cause. Small groups sometimes manage to sneak onto planes bound for England, where, of course, they are denied admission and put back on the plane to Kenya. But Kenya refuses to readmit them, because once an Indian leaves Kenya he cannot return except with a special visa. So these Indians begin a long trek, shuttled—without charge—from one world airport to another, until finally someone admits them—temporarily.

Because of the great distances these homeless groups travel, they have come to be called “migronauts,” and it is not unusual to meet these migronauts in the transit lounges of various world airports. I met one such group in Entebbe, Uganda, late last year—five teen-age boys who had only just begun their odyssey, having flown to Bombay, Entebbe, London, and back to Entebbe: “Only 15,000 miles so far,” said Virendra Desai, at nineteen the oldest of them. “We are human shuttlecocks in a long game. I wish someone would make a mistake.”

Those Indians still left in East Africa are gradually beginning to feel a rising hostility among the African masses. Fortunately there have been no incidents of overt violence so far, but unwanted and unclaimed, the Indians rather easily become the targets of witch hunts. Those Indians still trading are frequently singled out as the exploiters of the native population; the Indian community earlier this year was widely blamed—without presentation of any evidence—for a leakage of the national high-school examination in Uganda and Kenya; and last month Tanzania announced the nationalization of all property valued at over $15,000—but the New York Times correspondent there has reported that only property belonging to Indians has been expropriated.

The Indian community in East Africa is subdued and uncomfortable, and sometimes even fearful. The constant topic of conversation among the community is how best one can wrangle one of the 1,500 vouchers issued for entry into Britain each year, and large hordes will eagerly gather at the homes of those fortunate enough to win one of these vouchers to learn how the lucky ones presented their cases to the British Embassy. Every once in a while there are rumors in the community that Britain has decided to finally let all of its Indian citizens come “home,” while those more maliciously inclined circulate false news of massacres of Indians at the hands of Africans.

Two such rumors recently turned out to be true. A little over a year ago, an Indian family of four was ritually hacked to death in Nairobi. And last month the British government announced that it had doubled to 3,000 the number of Indian families who could enter Britain from East Africa each year. At that rate, it will take about twelve years for the unwanted and unemployed British East African Indians to make it “home.”

Salim Lone

New York City

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1971/oct/07/the-lost-indians-of-kenya/

Indians also VOLUNTEERED and fought alongside the British in WW1 and WW2, what status did they establish for themselves? In fact, if one goes back in history, we the East African Asians “the citizens of the Imperial British Government” have brought about a totally new meaning to this word “Immigration” and in doing so it has also showed up and underlined Colonialism and what it stood for, for its fellow citizens, on the base of one’s colour. We were British and not Kenyan citizens; we obtained our British rights through proper channels and wanted to exercise our right/s.

Thousands of British overseas citizens left stateless after decolonisation in the 1960s are to be given the right to live in Britain.

Rights of entry for former British nationals who were not born in the UK nor had a parent or grandparent born in the UK were removed in 1968. Mostly of Asian descent and living in East Africa, they were re-classified as British Overseas Citizens in 1981.

However, the countries in which they lived, such as Kenya and Uganda, also refused to recognise as nationals those who did not register at independence. This left thousands without any nationality or rights of abode.

1968: More Kenyan Asians flee to Britain

http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/4/newsid_2738000/2738629.stm

British nationality claims: The Case of the East African Asians

There is a large population of South Asians in East Africa. Their presence there dates back to the time of the British Empire when large numbers of South Asian workers were brought to East Africa by the British. Today, Kenyan Asians number 100,000. Tanzania and Uganda are reported to have Asian populations of 90,000 each.

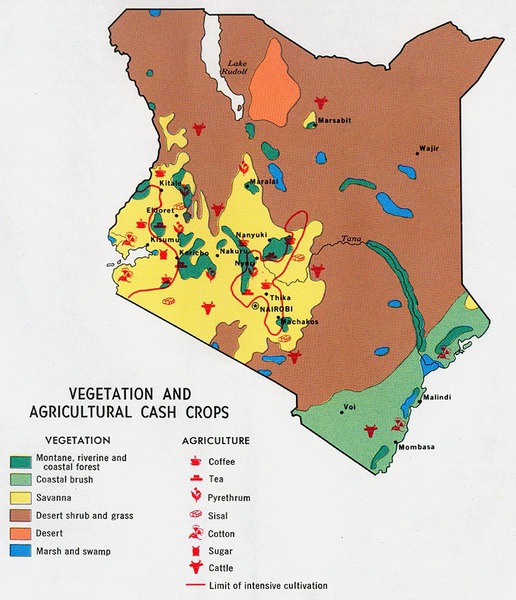

British East Africa Protectorate

The above maps show us the prime land allocation to Europeans as they were the only one's allowed to own. This was probably after 1904 when twenty- two Europeans met to elect a committee to encourage white settlement. The subject of their letter to Sir Charles Eliot, now Governor of Kenya was, ‘Seeking Government support for white settlers in Kenya and opposition to land and labour to Indians and also oppose Indian Immigration described as ‘detrimental to the European settlers in particular and the indigenous people in general'

Early 1880s

The Berlin conference of 1884-85 was held in Germany in order for European powers to agree on the regions in Africa each power had the right to ‘pursue’ legal ownership

of land. This conference marked the official start of the Scramble for Africa by European powers: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom (Britain).

http://www.enzimuseum.org/after-the-stone-age/british-east-africa-protectorate

1968: More Kenyan Asians flee to Britain

http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/4/newsid_2738000/2738629.stm

East African Asians: Escape to a New Life in Britain

Many East African Asians with British passports made the decision to settle in the UK. We explore their life-long journey in a new country.

The study investigated the emergence of a wage labour force in response to the ... of the Uganda Railway in 1895 to1901 marked yet another chapter in Kenya's….

http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_2_No_23_December_2012/32.pdf

East African Asians

1. General

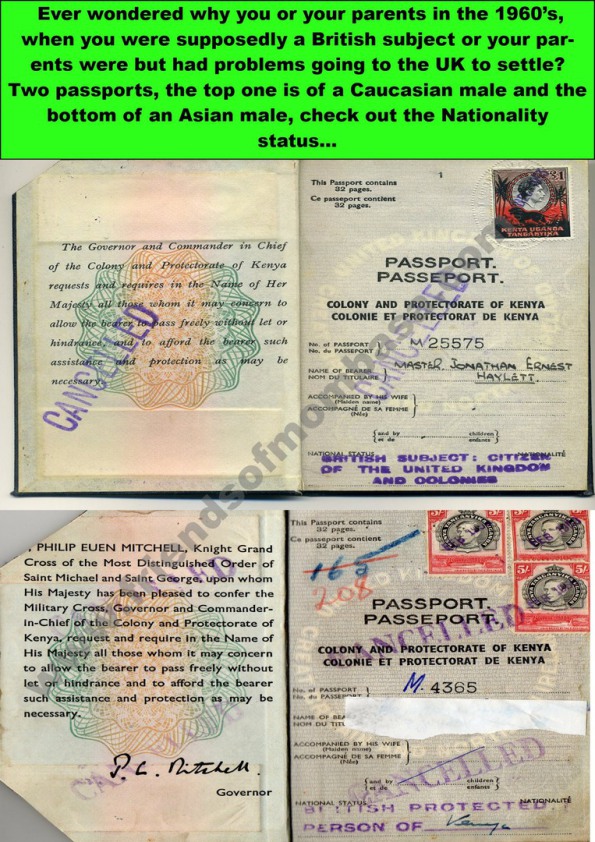

1.1 CUKCs of Asian descent residing in East African dependencies when those

colonies and protectorates became independent mostly retained their citizenship of

the UK and Colonies. As UK passport holders, they were thus (deliberately) excluded

from the scope of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962.

What are registrations of British nationality?

From 1949, people in the British Commonwealth could register their British citizenship to remain British citizens – whether or not they actually moved to the UK. Up until 1949 citizens of any colony or dominion in the British Empire were automatically considered British subjects but this changed with the British Nationality Act 1948.

People born in Ireland before 1949 were, likewise, considered British subjects and after the 1948 Act could also register British nationality; however, anyone born in the Republic of Ireland after 1948, seeking British citizenship, would need to apply to naturalise.

Registrations ended in 1981 and from then on all foreign nationals, whether from the Commonwealth, former British colonies or any other country in the world, have had to apply for naturalisation to become British citizens.

In 1883 also the ‘right of the Jurisdiction over British subjects in East Africa’ was transferred from the British Indian Government to the Imperial British Government. Consequently the Indian bourgeoisie had to channel their interests in East Africa via the markets in the Indian Ocean.

It was "Colony and Protectorate of Kenya"...National Status: British Protected Person of Kenya.....

Later on it was ...still Colony and Protectorate of Kenya...National Status: British Subject: Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies..

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.. National Status: British Subject: Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies.

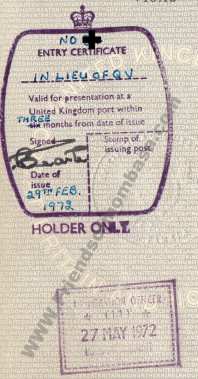

Below Voucher that had to be applied for..

The Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962

In 1960, the Home Secretary, Richard ‘Rab’ Butler, pressed for legislation, and the Cabinet appointed a committee. Butler oversaw the production of the Bill that became the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962. This controlled the immigration of all Commonwealth passport holders (except those who held UK passports). Prospective immigrants now needed to apply for a work voucher, graded according to the applicant's employment prospects.

The Labour Government won the elections in late 1964 with a tiny majority and was vulnerable to populist pressures exerted by a handful of right-wing Midlanders. One sign of the atmosphere of bitterness was the election of the Conservative Peter Griffiths in Smethwick. Griffiths had run a campaign under the slogan: 'if you want a nigger for a neighbour vote Labour' and on his entry to the House of Commons he was denounced by Prime Minister Harold Wilson as a 'Parliamentary leper'.

The prominent Conservative MP for Wolverhampton South West, Enoch Powell, began a populist anti-immigration campaign and the Labour Government introduced a new Act early in 1968. This new Act withdrew the right of entry of remaining Kenyan Asian passport holders and, for the first time, distinguished between citizens who were 'patrials' - those who possessed identifiable ancestors in the British Isles - and those who were not.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/in_depth/uk/2002/race/short_history_of_immigration.stm#1950

http://www.migrationwatchuk.com/Briefingpaper/document/48