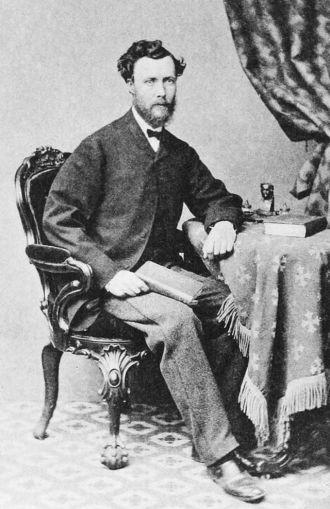

John Kirk (explorer)

John Kirk CMG KCB (19 December 1832 – 15 January 1922) was a Scottish physician, naturalist, companion to explorer David Livingstone, and British administrator in Zanzibar. He was born in Barry, Angus, near Arbroath, Scotland and is buried in St. Nicholas's churchyard in Sevenoaks, Kent, England. He earned his medical degree from the University of Edinburgh. He was a keen botanist throughout his life and was highly regarded by successive directors of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: William Hooker, Joseph Dalton Hooker and William Thistleton-Dyer.

British /Indian political influence in East Africa

Just as Indian Commerce increased so did British political influence in East Africa. In 1883 the growing momentum of the ‘scramble for Africa increased (British, Portuguese, Belgians, French, Germans, Italians etc..). Sir John Kirk was concerned that Germany paramountcy in Tanganyika would enable’ a rival nation to utilize the trading capacities of our Indian subjects to advance and develop her commerce’. Especially as Bagamoyo was the principle port in Tanganyika for the arrival and departure of the Ivory caravans with a large concentration of Indians operating from that port.

In 1883 also the ‘right of the Jurisdiction over British subjects in East Africa’ was transferred from the British Indian Government to the Imperial British Government. Consequently the Indian bourgeoisie had to channel their interests in East Africa via the markets in the Indian Ocean. That is, all their business ventures in East Africa were no longer connected with the Bombay Government as in the past.

1896…..Decision to employ Indian labour. Government of India insists that labourers who so chose should be free to remain in East Africa after completion of contracts. The general attitude of the Government of India caused consideration to be given in 1897, to the recruitment Chinese labour, but this was not pursued.

The coolies were indentured workers bound by a contract that offered them a monthly wage of 30 rupees and freedom to return to India at the expiry of their contract. Of the 32000 brought in by recruiting agents back in India, 26000 returned to India when the work was completed. Many are recorded to have been killed by the man eaters of Tsavo (2500 in total), and the rest with some clerical and technical skills were absorbed into the railway service. While the work of laying the rail was in progress others came in as small time merchants to cater for the needs of the large Indian work force and local African communities that resided along the planned rail line to Port Florence,now Kisumu.

In 1910 Sir John Kirk remarked on the work of Indian Traders in Nairobi: In fact drive away the Indians and you may as well shut up the Protectorate. It is only by means of the Indian Trader that articles of European use can be obtained at moderate prices.

Winston Churchill in “My African Journey”: It is by Indian labour that the one vital railway on which everything else depends was constructed.

Indians Trading in the Indian Ocean Regions

In most European’s minds the Indians simply did not matter. When writing of East African history in general, the role of Indians is ignored or slighted. It is the British that get the credit for ‘pluck and determination’ building the Railways even when it is admitted that Indians suffered untold horrors.

Even classifying the architectural styles in Mombasa’s Old Town, the authors of the “Conservation Plan for Old Town” deliberately called the Indian Buildings ‘Traditional Mombasa houses”. The assumption was that every Indian was a ‘coolie’ unless you were of a Goan back ground (mostly educated clerks).

Most if not all prime geographical areas were also chosen for themselves and area controlled by the British Europeans for the Europeans. The lack of information about Indians is due not only to the non-Indians’ disinterest (and often hostility). It is due also to the Indians’ own lack of Interest in writing about themselves.

There are good reasons for this. Whereas most of the Europeans who came to Kenya came primarily to have a more adventuresome life (albeit often with extremely hard work) in a lovely land, the great majority of Indians came out of desperation, to try make a living.

And whereas the European who settled or worked in Kenya came from a culture and class where writing a diary and publishing a book reminiscences were taken for granted, many Indians who came to Kenya were illiterate and those who were literate were not from a journal-writing culture. They recounted their adventure as oral history.

The presence of Indians in East Africa is well documented in the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea or Guidebook of Red Sea by an ancient Greek author written in 60 AD. The ancient Indian

work the Puranas also mention the East African coast as well interior of Kenya as far as Lake Victoria, which was known as ’ Nil (Nile?) Sarover,’ Lake Nil, and knew the source the of ‘Nil’

Nile.

The Indian sea merchants from the Gulf of Kutch and further south on the west coast of India sailed their seagoing dhows, large wooden ships with a huge lateen sails, aided by the alternating monsoon

winds. The North East monsoon winds brought these merchant sailors across the Indian Ocean to the African east coast from December to March. After trading and bartering, they returned using the

reversed South West winds from June to September.

They sailed regularly to the Zenj Coast where they traded in cloth, metal implements, iron nails, copper wire, glassware, wheat, rice, sesame oil, raw sugar, and salt.

Early contacts between Indians and East Africa go back at least 2000 years. And when Vasco Da Gama arrived in Mozambique, Mombasa and Lindi in 1497, he was surprised at the number of Arabs and Indians he found there. Obviously, Da Gama went to East Africa to find the sea-route to India, but many of today’s businessmen are happy to inform you that it was not Da Gama who discovered that route himself, but he was guided by the Indian Navigator Kanji Malam, who showed him the way to the South Indian Coast.

“ you want to know who was the first member of our family to be in Africa and when? Well, his name is Mohammed, he was known as “Kanji Maalim”. That name means’ master of the tille’, because in the language of Gujarat, which is where we Badalas are from, the word for tiller or ruder , is ‘sukhan’. He was the pilot who showed Vasco Da Gama the way from Malindi to India.

Most present day Indian families in East Africa have at least some memories of their (grand) parents’ migration and settlement histories. By far the most frequently heard one-liner were, ‘we came in Dhows’ and most came as young boys with little or no money seeking employment in one of the shop of family members or other community members. And then, after a while, that they started their own shops making long hours and working very very hard.

These above citations are from both well-known writers in Mr. Gijsbert Oonk and Ms. Cynthia Salvadori who both separately carried out their own researches about the Asians in East Africa.

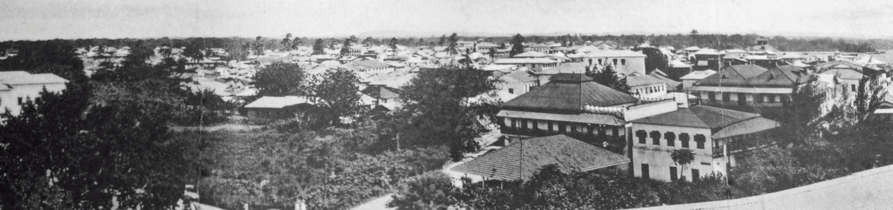

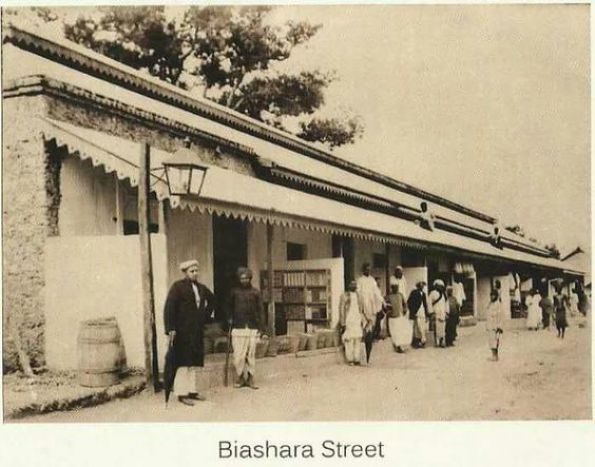

Zanzibar, East Africa

As important as the Arabs were the Indian residents in Zanzibar and the coast were perhaps more important, since almost the whole commercial and Financial Business on which the prosperity of Arab East Africa dependent, was in their hands. (professor R. Coupland In the Exploitation of East Africa, 1865-1890: The Slave Trade and the Scramble, 1939).

Winston Churchill, 1908: It is the Indian banker who supplied the larger part of the capital available for business and to whom even the white settlers have not hesitated to go for financial aid. The Indian was here before the British Officials.

Indian traders had a major share in marketing 60% of the copra and of the clove crop produced in Zanzibar, Indian Banks financed the caravans into the interior of Africa, offering credit. The flow of trade to and from India was an Indian Ship, two thirds of which went to Europe and America.

Frere remarked to Granville: Europeans, Americans and Swahili trade and make profit but the one link in this chain is the Indian.

Clove growers associations of Zanzibar was first nail in the coffin for the Indians who were in total control of the Economics and the Clove growing Industry in Zanzibar. The Colonial Government seen and sensed that the well-established powerful Indian Economic growing threat in different sectors of the region along the Coast of East Africa and Zanzibar would be devastating to their Colonial Rule and had to do something, they introducing “The Clove Growers Association (C.G.A) Decree.

The president of the Indian Association, Zanzibar, Mr Tayabali Esmailjee Jivanji said” The Clove Industry is a hundred years old…. Binder (Mr B.H Binder was appointed by the Secretary State for the Colonies to Conduct an Inquiry into its Operation) had not considered the past history of the clove Industry, had he done so he would have realized that it was the Indian Merchants who had brought the Industry to its present position of commanding world markets and being the major suppliers and consumers…….

|

East African Protectorate: 1895-1920 |

|||

|

The early years of the protectorate include several developments of significance in Kenya's subsequent history. One is the decision to

encourage settlement in Kenya's temperate highlands by farmers of European origin (this prosperous region subsequently becomes known as the White Highlands). The intention is to provide revenue for

the railway driven northwest from Mombasa to reach Kisumu on Lake Victoria in 1901. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The resentment of the indigenous population against the settlers is accentuated from 1904, when a policy is introduced of settling Africans on reserves. Meanwhile a third racial group complicates the protectorate's racial unease. Cont: http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ad21#ixzz37AjJdzoQ

The British in EA

The scramble for Africa in the late 1800’s through… In 1883 also the ‘right of the Jurisdiction over British subjects in East Africa’ was transferred from the British Indian Government to the Imperial British Government. Kenya was established a British protectorate in 1895 giving Britain complete control and protection over the state of Kenya. France and Britain, after a brief risk of armed confrontation, agree in 1888 on a demarcation line between their relatively minor shares of the coast. British East Africa (BEA) is a British territory which sits astride the equator of the Dark Continent. In 1889, BEA comprises the land which later becomes Kenya and the western part of what will later become Somaliland. Within a few years, the area which now is called Uganda is added to BEA (though it is still considered to be a separate country within it). During the “Imperialist” era of the nineteenth century Great Britain authorized the creation of four chartered companies and endowed them with extensive political as well as commercial privileges, Sir William Mackinnon’s company “The Imperial British East Africa Company”, chartered in 1888 was one of them.

British Empire Article http://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/kenyacolonialservice.htm

Indian Army during World War I The Indian Army during World War I contributed a number of divisions and independent brigades to the European, Mediterranean and the Middle East theatres of war in World War I. One million Indian troops would serve overseas, of whom 62,000 died and another 67,000 were wounded. In total 74,187 Indian soldiers died during the war.

The White Paper of 1923http://www.microform.co.uk/guides/R96995.pdfhttp://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/315078/Kenya/38091/The-Uganda-railway-and-European-settlement#toc38093

India in World War IIThe Indian Army began the war, in 1939, numbering just under 200,000 men.[1] By the end of the war it had become the largest volunteer army in history, rising to over 2.5 million men in August 1945.[1][2] Serving in divisions of infantry, armour and a fledgling airborne force, they fought on three continents in Africa, Europe and Asia.[1]

After the war, the British government hoped to advance farming in Kenya and encouraged migration there, offering former soldiers land in Kenya on easy terms. White migration to Kenya rose along with the growth in number and size of European-owned farms. And immigration from India had also been rising, with the Indians resenting the way in which Britain's colonial government in Kenya gave in to the demands of European settlers by imposing restrictions on Indian activities, preventing Indians from acquiring lands in certain areas and limiting Indian representation in legislative councils.

By 1920, the number of Europeans in Kenya was nearing 10,000, up from 400 at the turn of the century – against something like 2,500,000 blacks and maybe 23,000 Asians and 24,000 people of Arab origin. Many of Britain's recent migrants to Kenya failed at farming, but in general European agriculture recovered from its decline during the war years. The colonial governing council, consisting of European immigrants, stabilized the currency in Kenya.

The governing council passed a law forbidding whites to work as labourers on farms, and the governing council encouraged the development of a pool of full-time black agricultural labour to fill the need for labour on the more successful of the white-owned farms. The governing council passed laws to discourage growth of a rising black labour movement. And it passed a law against blacks growing coffee, responding to the fear of competition by white coffee growers and fear that black farmers would force up the price of black labour. |

|||

Eight Points of the

Atlantic Charter

South Africa gained its independence from Great Britain in 1934, though the African National Congress, which was formed 22 years

prior to South Africa gaining its independence, did not gain power until 1994. The "Wind of Change" speech was a historically significant address made by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan to

the Parliament of South Africa, on 3 February 1960 in Cape Town. The Republic of South Africa became independent in 1961, making the country 55 years old as of 2016, this surely must have had a

significant clout and rise to the Colonial establishment within to have started the ball rolling in terms of thinking and giving Independence to many African countries that were under British

Colonial rule. Since the independence question to the Colonies was first raised in 1941 some 20 years before the speech, it was high time, was it not?

Remember, the Atlantic Charter (August 14, 1941) was an agreement between the United States of America and Great Britain that established the vision of Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill for a

post-World War II world.

Mahatma Gandhi spent 21 years in South Africa fighting for the rights of the South African Indians in many ways, indentured labour was his priority. He was in South Africa from 1893 until 1914 the

beginning of WW1, later Mahatma Gandhi focused in getting India its Independence.

But it was Roosevelt, the US president, told Britain to extend the benefit of common principles of the Charter including that of self- determination to its colonies (India and Africa were British

colonies), apart from war torn European countries. Churchill was said to have rubbished talks of Indian Independence based on the Charter. Let us get that fact in order!

Taking the points of the Charter which elaborated on the post war aims of Britain and US, Mahatma Gandhi wrote to Roosevelt,

Mahtma Ghandhi wrote.. “I venture to think that the allied declaration (the Charter), that

the Allies are fighting to make the world safe for freedom of the individual and for democracy sounds hollow, so long as India and, for that matter, Africa are exploited by Britain, and America has

the Negro problem in her own home. But in order to avoid all complications, in my proposal I have confined myself only to India. If India becomes free, the rest must follow...

” Just six years after the declaration of the charter, India became Independent on August 15, 1947. The principles of the Charter also became the

foundation stone of the United Nations which was set up in Oct 1945.

http://americanhistory.about.com/od/worldwarii/a/atlantic_charte.htm

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Colonials never ever paid for any land, it is a known fact what the British government had in mind, naturally the Railway Committee at Home were intensely annoyed and made a great fuss in the matter, with the result that Sir George was given carte blanche to build the Railway- over any land, whether occupied or otherwise, and further, that, all the land thus taken over was to be the absolute property and under the complete control, of the Railway and that is a fact!

Only an oppressor or an illegal occupier could exploit in that manner and did exactly that, look into the land ordinance in the late 1800’s and early 1900's, it went on for years...

The so called coolies were indentured labourers, this was a form of slave trade, bound by a contract that made no sense at all, but covered the legality of the slave trade, yes, Slave trade was legal and so was indentured labour, a form of Slave trade.

As for farming Industry, read into it and you will find that the indigenous or and Indian was prohibited to own any prime land at all, restricted from growing certain agricultural products, deal in, sell them…etc.

All land belonged to Her Majesty the Queen, it was Crown land, in fact the ancestral homes /whole communities of the Indigenous were uprooted and relocated, and some were threatened and put under surveillance.

For the European or Caucasian or soldier, it was either free land or at a very low rate in paying through instalments.

As for WW1 and WW2, people of Africa as well as people of the Indian Sub-Continent had nothing what so ever to gain from it nor was it their war, but sadly a lot of foot soldiers and others died for the Queen and country…

White Paper of 1923

East Africa was, and is one of the most important areas for the overseas Indian communities, which, in turn, played a pivotal role in the formation of modern East

African societies. The role and status of the East African Indians, the Asians as they were called there, was not one and the same in every part of East Africa, that is, present Kenya, Uganda and

Tanzania. Putting aside Tanzania which was under German rule until the end of the World War I, the Asians' situation in Kenya and Uganda, both being British protectorates, was also different from

each other. On the one hand, in Uganda, from where the Asians would be expelled by President Idi Amin in 1972, the Asians and the African natives kept by and large good social relations and the

antagonism between them and the colonial government was not so severe yet during the colonial period. In Kenya, on the other, where even at present about 80 thousand Asians are holding an important

economic position, they had been faced with a serious political problem, the so-called 'Indian Question', in connection with which they had to fight a bitter fighting against the white colonist

community and the British colonial administration since the first decade of the 20th century.

The main subject of this paper is the 'Indian Question' in Kenya during the 1920s when the confrontation between the Asians and the colonists came near to explosion. It is generally pointed out that

the East African societies under the British domination, including Kenya, were composed of the three distinctively different racial or ethnic communities, that is, the white colonists backed up by

the colonial government, the Asians and the native Africans. And these three groups were said to have occupied a distinct political, economic and social status, i.e., high, intermediate and low

respectively. In addition to this state of affairs, mixed involvement of the British government, self-governing Dominions, the Government of India and Indian nationalists in the post-World War I

period gave the 'Indian Question' much more complicated aspects. The paper tries to describe the history of the Asian community in colonial Kenya and the process and development of the 'Indian

Question'. V.S. Srinivas Sastri, a moderate Indian statesman, who was delegated from India for political negotiations with colonial and British governments, said "Kenya lost everything lost" when in

1923 the Brirish Secretary of State for Colonies published a memorandum entitled Indians in Kenya which did not satisfy the Asian interests. This was one of the typical reactions of Indians who

showed a deep interest in the fate of their brethren in East Africa. But at the same time we must take into consideration the African point of view. B.A. Ogot, a famous Kenyan historian, writes in

his study on Kenya under the British rule;

It was the European-Indian struggle for the possession of Kenya that constituted the so-called 'Indian Question'. To solve it, a special conference was called in London by the then Colonial

Secretary, the Duke of Devonshire, in 1923. Both Europeans and Indians were represented, and each tried to win sympathy by invoking the principle of safeguarding the interests of the only group that

was not represented. The resulting White Paper satisfied neither of the protagonists. ... In trying to solve one form of racial conflict, the White Paper in effect created a more serious form in

proclaiming the policy of the 'paramountcy of native interests'.

COVER STORY: Filling gaps in history: Indians in East Africa

http://www.dawn.com/news/1075485

East African Asians in 1960’s

East African Asians include Gujaratis and Punjabis who had migrated from the Indian subcontinent to Africa and then from Africa to the UK. They include Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Some are Ismaili Muslims, a Shi'a denomination, whose spiritual leader is the Aga Khan.

http://www.minorityrights.org/5415/united-kingdom/east-african-asians.html

More Coverage by CNN

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/12/11/world/africa/kenya-railways-india/index.html