Mackenzie Maritime traces its origins to one of the pioneer British companies in East Africa; the Smith Mackenzie & Company.

Mackenzie Maritime traces its origins to one of the pioneer British companies in East Africa; the Smith Mackenzie & Company.

A private ledger, with first entries dating from March 1850, records that the senior partner, Robert Mackenzie, had invested Rs 32,505 (nearly £2500), William Mackinnon Rs 20,530 (nearly £1500) and James Hall, who also joined the company in its early days, Rs 19,082 (or just over £1000). The net profit for 1850 was calculated as Rs 16,171 and for 1851, Rs 68,604, equivalent to nearly £5000, which was distributed among the partners according to their initial investment. Thus, after approximately four years of trading (dating from 1847) the partners had received dividends in excess of the value of their original investment.

The most significant early entrepreneur in our sample, in terms of his role in the formation of partnerships which were subsequently to join the Inchcape Group,

was William Mackinnon. Originally employed by a Portuguese East India merchant in Glasgow, in 1847 he ventured out to Calcutta, at first working at a sugar refinery in nearby Cossipore. It is not

known whether or not he paid his own passage out. Shortly afterwards, he joined a fellow Campbeltown man who already managed a general mercantile business, dealing in importing British piece goods

and exporting local tea, sugar, hides, saltpetre, indigo, shellac and rice.

Lloyds provided another valuable agency,new offers came from all quarters.

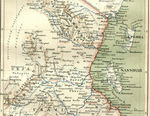

During 1887 Sir William Mackinnon was offered by the Sultan of Zanzibar a concession on the mainland. The imperial British East Africa Company was formed. Sir

William was the chairman of the B.I.S.N. Co. and the close connection between Smith Mackenzies and the I. B.E. A. proved a godsend. It was obvious that an office had to be opened in

Mombasa.

At the time there were no Europeans resident on Mombasa island although there were European missionaries at Freretown. Mr. W.J.W. Nichol was sent to Mombasa

to open the first mainland office. During 1877 Mr. E.N. Mackenzie died of malaria.

During the life of the I.B.E.A., Smith Mackenzie acted as financial and general agents for the organisation. In the mid-90‘s the I.B.E.A. surrendered their

rights over Uganda and East Africa and the British Government decided to build the Uganda Railway. A great burden of traffic fell upon the shoulders of Smith Mackenzie. B.l. Ships were employed in

bringing railway material to Kilindini while from Indian ports came coolies and foodstuffs.

At the same time the company was dispatching trading caravans to Uganda and fitting out caravans for other enterprises. In 1896 a branch was established at Kampala. An agency was procured for

petroleum products and £50,000 spent on tanks and equipment; later the company was given the concession for cutting mangrove bark at Lamu and an agency was set up on the island.

The first war strained the company’s resources to the limit, and it was during this period that branches were set up in Nairobi. Kisumu and Kampala; later

branches were opened in Dar es Salaam, Tanga and Lindi.

It would be impossible to catalogue in this small compass the interests of Smith Mackenzie and Co. Ltd., but the company has had a finger in every phase of

life in East Africa for the past century.

During the days of sea travel B.I. was the first choice and indeed its is remembered when seven B.I. ships were at the same time alongside the berths at Kilindini, busy with imports exports and passenger traffic, At one time associated companies were the main stevedoring and godown operators on the coast.

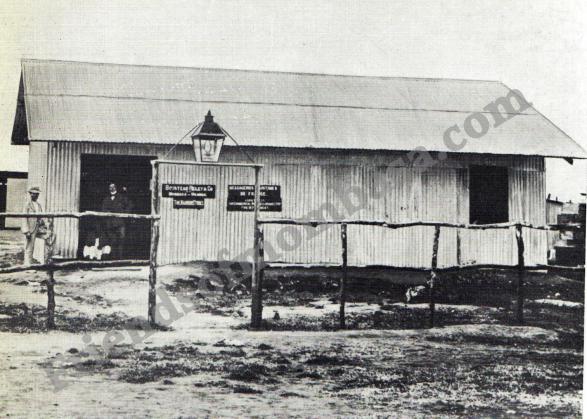

Smith Mackenzie Mombasa office in what was Vasco da Gama street at the beginning of the century later expanded to Kilindini Area,

Shimanzi..etc.

Going back to its history, it was against this background that the British Postmaster General opened discussions in 1871, which

led, in 1872, to the Bl’s contract for a service ‘to convey mails between Aden and Zanzibar once (each way) every four weeks’.

This linked the East African coast to the growing network of BI services, which already included the Indian coasting trade and the Persian Gulf. A new merchant partnership was formed to manage this

service and represent British commercial interests in Zanzibar and on the East African coast.

Smith, Mackenzie had already acted as the agents and supplier of local transport and labour to the African Lake Corporation of Nyasaland and Rhodesia, the East African Mission, the Equatorial African Mission and the Congo Association.

Yet, why was the British Government, notoriously cautious and hesitant in the question of making financial commitments overseas, prepared to grant a mail subsidy to aid the opening-up of an area which was out of the mainstream of European shipping traffic? Why was Sir William Mackinnon so keen to take up the challenge of providing this service? What was the impact of the BI steamers and the activities of their agents?

British mercantile interest in East Africa, as in many areas, began with (he trading activities of East India Company ships, which

developed when Zanzibar became linked to the Gulf State of Oman. Attempts to establish Omani control over the east coast of Africa culminated in the transfer of the Sultan of Oman’s court from Muscat

to Zanzibar in 1840.

This encouraged considerable international interest in this island trading post: an American consulate had been established in 1837, followed by the French in 1844. The East India Company revived

their agency at Muscat, which had been allowed to lapse until the appointment of Atkins Hamerton as political agent in 1840. The British already enjoyed a treaty relationship with Oman, so when the

Sultan changed his official residence to Zanzibar, Hamerton became the local East India Company representative and HM Consul there. The initial opening-up of Zanzibar in international trade brought

with it a large influx of Indian merchants and settlers - another reason for British interest.

The origins of the mail contract of the 1870s may be seen in the official correspondence, which declared that it was designed ‘not

merely for postal purposes, but also, and to a greater extent, with a view to facilitating communication with HM Naval and Consular establishments on the East coast of Africa for the abolition of the

slave trade’.

Britain’s commitment to the eradication of this infamous traffic had grown considerably during the course of the nineteenth century, but this was not the only reasons for the grant of a £10,000

annual subsidy. Another argument was the need for the improvement in communications (there was no cable link between Aden and Zanzibar until 1877) but this was not necessarily the deciding

factor.

In taking a financial interest in the Aden to Zanzibar route, the British Government was strongly influenced by the success of its

grant of a subsidy from Bombay and Karachi to the ports of the Persian Gulf ten years earlier.

This service had greatly benefited from the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, a development which may have played a part in the timing of the African contract, as it shortened the route from

Britain to Zanzibar by over 2000 miles.

One of the aims of the Gulf subsidy had been to combat Arab piracy in the area, but it soon became clear that a strengthened British commercial presence was also required for the extension of

British-Indian and British political authority in the area, against the threat of Russian ambitions. In the mime way, the Zanzibar subsidy, seen officially as a weapon in the fight against slavery,

was also aimed to encourage

British commercial interests and thereby political prepresentation - in a strategically important trading outpost in which the Americans and other European had shown considerable interests at that

time the export of clove was thriving too, Sir William Mackinnon saw this as an opportunity to inaugurate his mail services, this further meant the African extension to his existing route for BI

services.

Revolution in the carrying trade of Zanzibar that connected the island not only with Aden, but with Bombay, the Comoro Islands,

Madagascar, Natal and the Cape with the exception of a few small vessels in the coasting trade: concludes the whole of the commerce of Zanzibar is now conveyed by English tonnage.

The importance of these steamers is seen in entrances at the port. In 1874, British Steam vessels, totalling over 30,000 aggregate tons, called at Zanzibar. Their only rivals in the period were the

Germans. Who sent Steamers of a total of nearly 4000 tons to the port.

Otherwise sailing ships, of between 250 and 500 tons, (about 1500 tons in all) continued in the trade, registered in England, America, Germany, France, Norway, Portugal, Holland and Denmark and over

200 Arab Dhows continued to operate in East African Waters.

J. W. Buchanan, a Smith Mackenzie employee who had previously worked for another British firm at the port, Boustead, Ridley & Co., took over the responsibility for dealing with a new

account opened that same year - the Special African Mission. The results of the survey work undertaken by this mission led in May 1887 to a formal concession to the British East Africa Association

(which became IBEA) to explore and administer the area. A lease of the customs administration of Zanzibar had first been offered to Mackinnon by the Sultan as early as 1877. The BI presence at this

port had always been especially favoured. Just before he died, E. N. Mackenzie accepted the concession on behalf of the Association, and accompanied General Sir Lloyd Matthews, with the British

military forces, on a tour of the hinterland of Mombasa to make treaties with the native chiefs.

IBEA took over the running of the new Bl service direct from London at Mombasa, but the extra business that Smith Mackenzie gained from the IBEA agency well made up for this. For example, four vouchers certifying the handling of supplies for IBEA by Smith Mackenzie in 1888-9 have survived, concerning a piece goods shipment, a Masai interpreter for the projected Uganda railway survey, local porters, and two Snider rifles with ammunition.

From the early 1880s, Smith Mackenzie had been responsible for the import of a large quantity of guns, rifles, percussion caps and cartridges, the landing of which required the consul’s

permission. In 1881 alone, the firm imported over 5000 guns, over 9000 rifles, over 2 million percussion caps and nearly half a million cartridges. These were primarily for the use of naval personnel

and for the Sultan, but by the late 1880s and early 1890s, they were imported for arming the caravans of porters into the interior which IBEA organised. Smith Mackenzie also supplied IBEA with

dynamite mid detonators for their mining ventures, bullocks for transport, and copper, rice and other consumer goods, mainly from Bombay.

They also imported the Lake steamer Sir William Mackinnon, in sections, for local assembly. The firm also carried locally-grown exports, the production of which IBEA helped develop, such as tobacco

grown at Mombasa: 1,705 lb. were shipped to Bombay on board the Purnlia in 1890. Alhough inferior tobacco, its low price produced a steady demand.

Smith Mackenzie also acted as the official agent for the East Africa Protectorate on its formation in 1895, and

played an important part in the winding-up and liquidation of its predecessor, IBEA. Its Mombasa branch was promptly reopened in 1895, taking over IBEA’s lighters, Marine equipment and other assets.

It was to play an important part in the building of the Uganda Railway, importing supplies and foodstuffs for the Indian labour force as well as many of the necessary raw materials.

Started at Mombasa in 1895, the railway line reached Nairobi in 1899 and was completed, terminating at Port Florence on Lake Victoria, at the end of 1901. It cost the British tax payer at least

£5-5m.

Smith Mackenezie’s prominent position in the maritime trade of Zanzibar was formally recognised when it was appointed Lloyd’s Agents in May 1884 for the region covering nearly the entire East African coast. From Delagoa Bay to Cape Guardafui.

In its work in organising caravans, Smith Mackenzie came under considerable criticisms in correspondence between British military personal and the Consul: it apparently made no attempt to improve the practically impassable road between Kibwezi and Kikuyu; Pordage and Martin, the local Smith Mackenzie employees, had little experience of mud transport problems; and no alternative had been found to the constantly diminishing supply of local porters. However, it would have cost at least £600 to metal the road surface - a cost which the Protectorate was not prepared to undertake - and Smith Mackenzie did try to provide local assistance by appointing an agent there. Boustead Ridley, who also covered the area, was also subject to complaints.

Smith Mackenzie at least tried to improve the lot of the porters it recruited, by providing medical facilities, disciplining cruel and over-zealous headmen, and by building shelters at suitable points along the caravan routes provided with blankets and clothes for the porters. The importance of the firm in the development of the East Africa mainland was to grow considerably in the first half of the twentieth century.

Smith Mackenzie’s activities in this region also included acting as the agents for Reuters, various insurance

companies, petroleum firms and for the producers of number of consumer items in Britain and Europe.

The expansion and consolidation of Smith Mackenzie’s activities before 1914 enabled the firm to survive and prosper between the wars

In 1914-18 its work in supplying coal for the British navy took on a new significance: the marine side of the firm’s business became virtually a annex of the Royal Navy.

The company found its resources severely stretched with the combination of the increased workload for its lightermen, stevedores and wharfingers through the movement of troops, armaments and provisions, and the depletion of its workforce with a large number of employees joining the armed services. The need for more capital to finance the company’s expanding operations was partly fulfilled by hiving off its shipping activities into a separate concern, the African Wharfage Company.

Its capital of £100 000 was divided into ‘A’ and ‘B’ shares, of which only the ‘A’ shares carried voting

rights. Smith Mackenzie’s shipping operations then lost much of its independence as, although it became the general manager of the new company, it held only non-voting ‘B’ shares. The BI and Union

Castle remained a controlling interest through holding the ‘A’ shares, by which it aimed to ensure greater financial security for its East African agencies, but it is significant that it still wished

to retain the management expertise of Smith Mackenzie.

The high wartime prices for local produce aided the economic development of Kenya and Uganda, and of the former German colony of Tanganyika, which became a British mandated territory after the First

World War.

Smith Mackenzie had managed to continue its trading and agency activities, and opened several new branches. Between 1916 and 1923,

new offices were opened in Nairobi, Kisumu, Kampala, Dar-es-Salaam, Tanga and Lindi.

A glimpse of life at the Lindi branch just before the second World War has been given by an ex-African Wharfage Company employee, John Hall.

He recalled that there were only twenty- seven Europeans in the town, and a further fifty in the district, that there was no

electricity, and only one water closet in the whole settlement until he installed another in his flat over the office.

Local water and meat were highly suspect, so the former was brought from the other side of the harbour in old petrol tins and the latter purchased from passing ships. Despite isolation and the lack

of luxuries, Hall and his wife (married at the port in a ceremony attended by every European inhabitant except one), regarded life as very enjoyable. His pay was low - only £45 a month,

but chickens were only 1/- each, and a local fisherman would deliver fish every day for a month for only 6/-. Hall managed the Lloyd’s

Agency at the port and supervised the deployment of his company’s craft, nearly all of which were built at Grimsby and shipped out in parts.

A relic of the First World War, an old wood-burning stern-wheeler, the Tomondo, was still in service, carrying produce and passengers up local rivers. The African Wharfage Co. soon established its own subsidiaries, including a branch in Tanganyika and the African Marine and General Engineering Co. in Mombasa.

Meanwhile, Smith Mackenzie’s general produce trade declined, influenced by the demonetisation of British gold sovereigns and the

increase in import duty to 10 per cent. Its agency business remained successful, but it soon became clear that new capital resources, and a stronger link with London rather than Calcutta, was

essential to its firm became Smith Mackenzie and company ltd, registered in Nairobi, with a share capital of £280,000 which had increased to £580,000 by 1937.

The original partners of the firm were all long established Smith Mackanzie men: W.J.W Nicol; J.W. Buchanan; W.A.M. Sim; W.F. Jenkins; W.G.D.H Nicol; H.H Robinson; S.H.Sayer; W.M.Buchanan and N.J. Robinson.

Boustead and Ridley...click below