THIKA (Part 1)

A long walk to Karamaini

by C W

P Harries

Early in 1904 Father, my brother Cecil, Uncle Willy and a friend set out on foot to inspect the various areas in which land for settlement was being offered

by the Protectorate Government. (It was all in districts supposed not to be occupied by Africans, in so-called ‘buffer areas’ between peoples often at war). They had to carry all their requirements

and had no horses.

The first area they inspected was Limuru, Kiambu, Thika, Makuyu and Ruiru. Having done this they went to the second area, Nyeri, Nanyuki and Timau. They

walked all round and up the hills and then decided to inspect the third area, Naivasha. So from Timau they walked over Mount Kinangop and round Lake Naivasha. They caught a train to Lumbwa and walked

all round Kericho and Sotik.

They only took bare necessities, and slept on the ground in the open. None of them had raincoats and each time a storm of rain came they were drenched. They

all wore huge Indian pith helmets, and Uncle Willy objected to getting wet, so whenever rain started he stripped and put all his clothes under his helmet and marched on, starkers. When the rain

stopped he would dress and be quite dry whilst the others were shivering in their wet clothes.

On completing Kericho-Sotik they walked to Port Florence, now called Kisumu, and took the train back to Nairobi. Father decided that he liked the Chania Bridge area best. (The name Thika was adopted later.) He then came out with a Government surveyor and put in one peg, not far from the Ndarugu Heights signboard, and told the surveyor that he wanted four 5000 acre farms, two for himself and two for his son-in-law, Herbert Cowie, Mervyn Cowie’s father. The dividing line between his and his son-in-law’s farm had to be a straight line from the peg to the Aberdares. Father’s two farms were from the left of the straight line.

along the Kikuyu land unit, down the Theririka and so back to the peg.

Mother, my sister Ina, my brother Oswald and I arrived in Nairobi in July 1904. Mother brought in the first piano and the first real cooking stove to British East Africa. I was four years old and was

carried out to our farm, Karamaini, on an African's back, and have been there ever since.

There were thousands of acres of forest then and our farm was full of game. Right through it ran a deep elephant track that had to be filled up before we

could plough. Buffalo skeletons were everywhere. The forest was full of very large game pits which were used to trap buffalo, and to this day the remains of these pits can be found. Seventeen rhino

were shot on the farm, many lions, and over 50 pythons, one of them 23 feet long. Red-legged Spurfowl were so plentiful that the totos used to trap them and sell ten for one rupee. We used to cage

the birds, as they proved one of our staple foods. In 1917 1 trapped 37 leopards. I shot the one and only lion in my life at the age of 11.1 was given a 20-bore shotgun and used to make my own

cartridges, using blasting powder. One day I ran short of pellets and very foolishly used old gramophone needles. I killed a warthog with this queer cartridge but it ruined my gun. I received a good

hiding and was forbidden to do any shooting for a year.

My brothers tried rearing ostriches. They marked nests on the Tana plains and herded the chicks back to Karamaini, where they were penned. When the feathers

were ready, my brothers took them to Kisii and exchanged them for cattle - the number that could be held between thumb and forefinger bought one cow. Then the cattle were driven down to the Nairobi

area to be sold for cash. Feathers were also exported until suddenly the fashion changed and ostrich farming came to an end.

In 1910 Father planted our first coffee trees, really because Mother thought the bush so attractive with its glossy leaves, fragrant white flowers and red berries. By 1955 there were 360 acres of

coffee, about one third of it irrigated.

In 1908 no crops had been proved in this area. My father and brothers tried everything they could think of including wheat, potatoes, cattle and sheep.

Disease, thefts and lions played havoc with the cattle and sheep, there was no market for the potatoes when they were ready, and wheat just did not do at all. It was a hard struggle to make ends meet

and for several years we only managed to exist by selling portions of the original 10,000 acre farm to other would-be settlers.

Despite all the hardships Mother’s courage never failed, and soon after 1910 she managed to establish a small herd of native cows. They produced enough milk

for her to start a butter trade with the Europeans living in Parklands. The only means of transport then was a donkey wagon which went to Nairobi every two months and took two days each way.

Obviously this could not be used to take the butter, and my mother engaged a Kikuyu who carried 40 lb. of it on his head, and came back the same day bringing the household groceries. For this he was

paid 50 cents.

We lived cheaply then with plenty of birds and buck for the pot and an abundant supply of vegetables from my mother’s garden. This was down on the banks of the Ndarugu River, some two miles from the

homestead.

She worked down there alone most days, or with one of us younger children as a companion. She planted many kinds of fruit trees and some of them did extremely

well, so that in due course she was able to supply the surrounding farmers with pawpaws, mangoes, bananas, loquats, oranges and lemons. Every Friday morning there would be a queue of Africans waiting

with their kikapus and these were filled at 2/- each.

My mother was the true founder of the pineapple industry. In 1905 her son-in- law, Herbert Cowie, went to live in Nairobi where he had a large garden. He

imported many kinds of fruit from South Africa, pineapple suckers among them. Probably these originated in Florida. They didn’t seem to thrive, so Herbert Cowrie uprooted them and threw them over his

garden fence.

My mother had shown interest from the start in these pineapples, and was horrified to hear that they had been thrown away. She saddled her donkey, inspanned

the wagon, went to Nairobi and collected the cast-away suckers. Today, apart from some grown by Libby, McNeal and Libby, it is thought that those original 200 suckers imported, thrown out and

rescued, are the parents of every smooth-skinned pineapple in Kenya.

Under her care the cast-offs thrived, we increased our acreage, and when coffee prices slumped so disastrously, they provided our only income. Without them we

could never have held on to the farm. They paid for our first tractor, and in 192 7 for Mother’s first real holiday.

Our usual mode of transport to Nairobi was by donkey cart. We used to leave in a small wagon pulled by about ten donkeys. It was customary to spend the night

in the forest just beyond the Kamiti River, and reach Nairobi by mid-morning. This trip was usually biannual. After an enterprising business opened at Ruiru, people were able to buy dry goods at the

Scots Town Stores.

The opening of a branch line to Thika in 1912, called the Thika Tramway, was a great event. A passenger could board the train at any spot between Nairobi and

Thika by standing on the rail and holding up his hand. Similarly a passenger could inform the driver at Nairobi Station at what mileage and telegraph post he wanted to alight and the train would stop

for him.

Twice a week, Monday and Friday, a farmers’ train was run from Thika to Nairobi and back. Many farmers used to give Mr Good, the permanent guard of the train,

their cheques, and when the train returned in the evening Mr Good used to hand out bags of money all along the line. Everything went into the carriages. Lizzie Barnes of the Scots Town Stores always

had bags of flour, potatoes, onions, etc., in the carriage, her goods stacked in one, whilst she travelled in another compartment. One passenger carried a 20-foot length of four- inch piping tied to

the running board of the carriage.

Mother died in 1941 - before the opening of the canning factory at Thika (1950) which now takes thousands of tons of pines, grown mainly by Africans, from within a radius of 50 miles. I believe it is the second largest in Africa.

RICH HISTORY: The first descendents of Asian origin to settle in Thika.

At the beginning of the last century, the first people of Asian descent started migrating from India to Kenya in dhows. By then, Thika was a main centre after embarking at Mombasa.

The earliest to settle in Thika – Shah Meghji Ladha and Meghji Kanji – coming to the area in 1910.

Later some more Indians settled in Thika, near the present day Blind School, with others settling in Makindi which was about 7 kilometres away.

They lived in wooden and iron sheet houses and used water for their domestic use from the nearby Chania River. There was no electricity until 1924 and Thika Water Works also started thereafter.

They had a passion for business in their blood and soon started small scale businesses after the First World War. In the old clock tower still planted at the roundabout (Githaa-ini) on Kwame Nkrumah Road, stood provisional and agricultural stores.

|

Mepa Punja Shah during the opening ceremony of their new construction in 1957. |

Kenya's Golden Harvest- a Thika Industry

KENYA’S GOLDEN HARVEST — a Thika Industry Part 11

In East Africa as elsewhere, the growing of fruit and vegetables is subject to the vagaries of the weather. To avoid the evils occasioned by extreme fluctuations in supply and thus ensure a stable market, canning must be resorted to in order to satisfy the requirements of both local consumers and exporters. Canning has another advantage, in that it can absorb the products of peasant agriculture in addition to those produced under dose supervision of the factory. For this reason it is an industry indispensable to the newly emergent African countries.

Kenya Canners Ltd. was formed in 1949. It was not however until 1950 that production was started, when less than 100 tons of pineapple was processed.

The next 4 or 5 years showed a steady increase, but they were very largely years of experiment, not only in regard to manufacturing techniques, but also in connection with the growing of pineapples and vegetables for the cannery.

The progress of the industry can best be illustrated by the following figures, showing the value of sales since

1956.

Pineapple Vegetable Total

£ £ £

1956 526,995 56,150 583,145

1957 433,927 56,959 490,886

1958 418,929 55,446 474,375

1959 273,446 68,306 341,752

I960 316,178 91,706 392,586

1961 284,971 105,128 390,099

1962 (8 months) 441,920 73,266 515,186

It is interesting to note that total sales during Lhe first 8 months of 1962 were more than 30% higher chan for the whole of 1961. It is confidently expected that total sales in 1962 will be

at least £750,000. Of :nis approximately £150,000 will be in the East African territories, and £600,000 or 80% of the total, will -e exported, in order of importance, to the following markets.

£

1. United Kingdom 150,000

2. Germany 100,000

3. France/Belgium 80,000

4. Arabia 70,000

5. Scandinavia 40,000

6. U. S. A./ Canada 20,000

7. New Zealand 15,000

8. Italy 15,000

9. Somalia 15,000

10. Rhodesia/Nyasaland 15,000

11. Other countries, including

Finland, Holland, Spain,

Lebanon, India, Ethiopia, etc. 80,000

--------------------

£ 600,000

----------------------

Of the total expected sales of £750,000 in 1962, approximately £600,000 will be Pineapple products, ind £150,000 Vegetable products.

The following figures show the very important contribution made by African growers in the supply of Pineapples to the cannery.

Received

Received Total Pineapple

from

from received

and

European African processed by

Growers Growers Kenya canners

(tons) (tons) (tons)

1956 7,060 4,711 11,771

1957 4,672 3,378 8,050

1958 5,317 4,850 10,167

1959 5,041 2,229 7,270

1960 5,194 2,920 8,114

1961 4,960 3,325 8,285

1961 (Estim.) 9,000 7,000 16,000

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

41,244 28,413

69,657

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1963, it is expected that the cannery will receive about 20,000 tons, of which about 50% will be supplied by African growers.

To emphasise further the importance of Kenya Canners Ltd. to the African economy of Kenya, the following figures may be of interest:

1. Paid to African employees—

(a) during the whole of 1961 £36,300

(b) during the first 8 months of 1962 £41,200

2. Paid to African Pineapple and Vegetable growers—

(a) during the whole of 1961 £41,600

(b) during the first 8 months of 1962 £54,400

Total for the past 18 months or an average of £9,640 per month £173,500 The present average number of African emplo¬yees is 600.

Now that the African growers are showing increased interest in the growing of Pineapple and Vegetables for the cannery, there is every possibility that in 1963, total sales may reach the one million pounds sterling mark. Kenya Canners can therefore look forward to a bright future, provided production costs can be kept within reasonable limits, and world prices do not drop appreciably below the present rather low levels.

East African Railways and Harbours

Nairobi to Nanyuk

http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/eastafricanrailways/NairobiNanyuki.htm

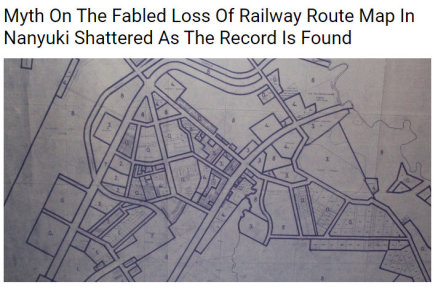

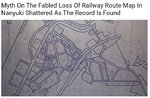

Myth On The Fabled Loss Of Railway Route Map In Nanyuki Shattered As The Record Is Found

A myth is told of how the map guiding engineers constructing the Nairobi-Nanyuki metre gauge railway in 1930 got lost as they made merry in Nanyuki town, thus

effectively cutting short the progression of the railway to Northern Kenya.

However, the myth has been shattered by lands officials in Laikipia after they produced what they claim is the original map that clearly indicates there had been an intention to extend the railway

line beyond the Nanyuki terminus towards Meru and Isiolo.

Heritage Trust Kenya

We aim to help Kenya preserve her heritage for the benefit of future generations

Our Nanyuki Town Plan is dedicated to the preservation of these green spaces. But we will only succeed with the engagement of our citizens

County Government of Laikipia·

https://www.facebook.com/County-Government-of-Laikipia-173537876066137/

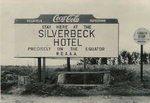

The Hook Brothers and the Silverbeck Hotel

Logan Hook, tall and handsome, a submarine commander in the First World War, went to Kenya in 1921. He took his family to Nanyuki where for 15 years they lived in a grass house which cost them £15.00 to build. As they knew nothing about farming, they established the Silverbeck Hotel exactly on the Equator. It was built by two Sikhs in exchange for Logan’s motorbike and sidecar. The line of the Equator ran straight through its bar, enabling customers to quaff half their drinks in the northern hemisphere and half in the southern. Twelve bandas, each with their own bathroom and outside loo were built for the guests, in a semicircle. Bath water was carried in debes because there was no running water or indeed electric light. In the middle of the semicircle was the main building, a grass-roofed bungalow with a wide veranda occupied by check-covered armchairs. Logan and his brother Raymond took safaris to collect rainbow and brown trout spawn to stock the rivers Burguret, Nanyuki, Ontelele and Sirimon.

https://oldafricamagazine.com/the-hook-brothers-and-the-silverbeck-hotel/