FORT HALL...Murang'a

Why was Murang’a called Fort Hall and reverted back to its original name Murang’a?

“Stories of Pioneers” (edited by Arnold Curtis) and to my surprise a lot is written about Mr Francis Hall.

He comes across as a decent man arriving in Mombasa 1892 to work for “The Imperial British East Africa Company” and since it seems like all his recollection/ reminiscences comes from his constant

written correspondences to his father, that were later extracted to give us a sound insight that takes us back in time.

In 1892 saw some serious road-building required for the operations of the Imperial British East Africa Company and for the growing numbers of caravans to Uganda. Major Eric Smith had built for the company a station at Kabete in Kikuyuland. It was situated about two and a half miles north of the post at Dagoretti established by Lugard two years before, and eight miles to the west of the future Nairobi.

Francis Hall was later posted and relocated in 1893 and had orders to make a road between that place and Machakos, the station of his nearest colleague, John Ainsworth, he writes on 1st May 1893 describes the job: I think I told you that I have to make a road from here to Machakos, thence to Kibwezi. I started this about a fortnight ago, having taken a rough survey of the best line of country.

Four months later Hall took the first bullock cart over the new road. It took two days to do the 24 miles to Athi River and another day to Machakos.

Since all the caravans going up-country stopped at Fort Smith and made constant demands for supplies, trading cloth against food with the frontier Kikuyu, Hall though he had better experiment with crops to supply to station and possibly assist the local cash crops.. Francis Hall reported all that to his father in his letter to him.

Most importantly he writes quote: Stuart and Rachel Watt and their four children were among the early visitors. The family stayed at the fort while Watt set out to try and start his

mission in Murang’a … and continues…this letter dated 14th January 1894….

It is very clear that the name “Murang’a” is a location that is mentioned clearly by Francis Hall in the letter to his father therefore it is evidently clear that the name “Murang’a” and its

existence in geographical location was recorded in a letter dated 14th January 1894.

Now, the question remains if the British renamed “Murang’a” as Fort Hall and it has rightly now taken its original and authentic name back as “Muranga” from Fort Hall!

Fort Smith, Kikuyu, Kenya, ca.1901

"Gov. Fort, Kikuyu." Exterior view of a camp with a number of tents, and huts in a fenced area. This is Fort Smith, a government station a few miles from the Kikuyu mission station. The mission had moved here from Kibwezi in 1898 under the leadership of Thomas Watson. The mission was transferred into the care of the Church of Scotland, 1901, which placed Dr David C R Scott and Dr Uffman in charge.

This image is from a collection of photographs which possibly belonged to Dr Karl Uffman, son of Dr Henry Uffman of the Leprosy Asylum in Purulia, West Bengal. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and joined the Kikuyu mission from 1901 to 1905

Why was Fort Hall given that Name and who was Frank Hall ?

Hobley - 1892 - At Fort Smith we met Frank Hall, a gallant soul, who did more than any living man to establish the pax Britannica among the Kikuyu, who were then a very turbulent and treacherous tribe.

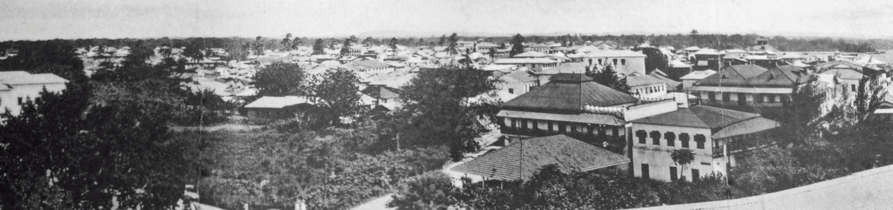

Many of you will remember Murang’a as Fort Hall, and you may have wondered at the name. When the railway reached the end of the Kapiti plains in 1899, it was half way to its final destination – Lake Victoria.

The directors decided to build a depot on the boggy flat ground they began to call Nairobi before tackling the uphill gradient to the lip of the Rift Valley and the precipitate descent down its wall. This meant that Fort Smith, a few miles uphill from Nairobi, and for many years the government station on the route to Uganda, was no longer needed as a staging post. It was decided to abandon it and establish a centre in Nairobi instead. John Ainsworth, the government representative in Machakos, managed to bag the coveted administrative post in Nairobi and this meant that Frank Hall, who had been at Fort Smith since 1892, was relegated to Machakos, much to his disgust. He felt (and he was probably right) that he understood the Kikuyu better than any other white man. He was certainly fluent in their language and in Swahili. Finally Hall managed to get back into the Kikuyu area when the government decided to establish a post at Mbirri and asked Hall to build it.

Hall fell prey to a rhino, later on in time, a leopard bit his knee and the poison spread throughout his body..(Old Africa)

https://oldafricamagazine.com/why-was-fort-hall-given-that-name/

Hobley - 1892 - At Fort Smith we met Frank Hall, a gallant soul, who did more than any living man to establish the pax Britannica among the Kikuyu, who were then a very turbulent and treacherous tribe. He was a nephew of the great Lord Goschen, and started life in the Bank of England, but his adventurous spirit could not tolerate dull routine, so he soon relinquished an office stool and went out to South Africa, where for many years he led a very varied life. He eventually turned up in EA, and was sent to assist Captain Eric A.E. Smith in Kikuyu, later on being given charge of the district. He was a charming personality, a mighty hunter and the prince of good fellows. He was badly mauled by a rhino and later on by a leopard, which encounters left him lame. A few years later he founded a station in Northern Kikuyu and unfortunately died there, this station being named Fort Hall in his memory. ...(Europeans in East Africa)

Murang'a

Murang'a is located between Nyeri and Thika. The town of Maragua is located 10 kilometres south of Murang'a while Sagana town is 15 kilometres northeast. It lies on a latitude of -0.7167 (0° 43’ South) and longitude of 37.1500 (37° 8’ East)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murang%27a

List Of Sub Counties In Murang’a County

This is a list of all sub-counties in Murang’a County. Murang’a is one of the 47 counties in Kenya which is located in the former Central Province and covers an area of 2,326 km².

https://victormatara.com/list-of-sub-counties-in-muranga-county/

How I Keep House in Kikuyu.

BY MRS. FRED SNOWDEN, OF RAILHEAD, KIKUYU, EAST EQUATORIAL AFRICA.

KEEP house among the “Waks.” Now, “ Waks ” is not the name of a family such as the Browns, Joneses, or Robinsons who live next door to one in England or

America, but an abbreviation for the Wa-Kikuyu, or interesting inhabitants of Kikuyu, in East Equatorial Africa, among whom I have now been living for three long years. I am sitting writing these

lines in the quaint bungalow of which I give a photograph on this page.

Not so very long ago lions used to walk round it at night, but of course the progress of the Uganda Railway is changing these interesting phases of life. But what a place for any ordinary woman to

keep house!

I seldom see a white stranger, am hundreds of miles away from shops of any kind, and, indeed, thousands from one worthy of the name. My very servants, as you will see, are reclaimed savages, and my

life is as different from that of my European sisters as could well be imagined.

How many of you, I wonder, know of Kikuyu and its locality? Not very many, perhaps, except those among you who have relatives or friends out here. Unlike the southern portion of this vast continent, it has not been boomed on account of its gold-fields or made famous by a Raid. Still, Kikuyu has a future in front of it; it is a fertile and picturesque region some 330 miles from the coast and about midway to Uganda. The Uganda Railway, by the way, starting from Mombasa, has now reached here, and will make Kikuyu its future head-quarters.

Ah ! and what a change that will mean. For one thing, the natives will then begin to know the coined rupee, whereas, until a week or two ago, our currency consisted entirely of beads, brass wire, and calico—very bulky, it is true, but still a very interesting method of barter, from a woman’s point of view.

As you may suppose, I found it ever so strange at first to buy a lot of sweet potatoes, a quantity of Indian corn, a huge bunch of bananas, and the like—all for a couple of strings of funny little beads, or a “hand’’(not quite half a yard) of common calico. Then, again, instead of going to the butcher’s shop, you run out with a blanket and bring back a sheep or a goat. And, oh ! what a space the trade goods take up. And the number of porters required to carry them, each load weighing not more than from 6o lb. to 65 Ib., for porters are careful, conservative creatures, given to grumbles and strikes.

I find my servants quite delightful now, but, of course, they were very strange to me when I began housekeeping. First in importance comes the cook, and after him the kitchen-“maid ”; then the upper and under house-“ maids.” All my civilized sisters, who are perpetually running backwards and forwards to the registry offices with fees, would be amazed if they could realize what excellent servants these tutored savages make — always provided that they have clean and honest instincts, in the first place.

Of course, they require training, these excellent fellows. Not one of the group a short time ago knew the right end of a fork or the use of a dish. Now, however, they pride them-self enormously on their work, and if one of their number makes a blunder of any kind he is promptly called a “goi-goi,” or know-nothing, by his fellows, and generally treated with a magnificent contempt. It is comical, too, the way they look down upon their naked compatriots, who are, of course, immeasurably inferior to them now—mere low niggers. They are not “Waks,” by the way, for these four servants of mine came from the remote and mysterious district of Kilima-Njaro.

The Wa-Kikuyu, I regret to say, are almost impossible as servants, so attached are they to their alarmingly scanty “costume ” of red earth and grease. I don’t want to dwell upon this, but it is obvious that a great change must take place in the attire of the average Wak before he can graduate as a decent and respectable house-boy.

My servants are kept pretty busy, for—strange as it may seem — we have quite a number of visitors and callers, who require

refreshments, of sorts. Do not be alarmed if I present to you three of our most interesting and typical visitors in my next snap - shot, which was taken on my own veranda. The tallest man of the

three, looking at himself in the hand-glass to see if his dress is both elegant and becoming and agreeable to the white lady, is a local chief of considerable importance.

His great weakness, I am sorry to say, is a mirror, and the very first thing he asks for when he comes to see me is my favourite hand-glass, with which he inspects himself complacently, as we see him

doing in my snap-shot.

The sons of big chiefs, too, occasionally drop in, for they appear to spend their time trotting about with a spear and visiting their friends, mainly black friends. Round their necks they wear numerous strings of coloured beads, whilst their bodies are smeared with red earth and grease in a rather alarming and warlike manner. The ear-rings of these gentlemen are also peculiar. The lobe of the ear is cut at an early stage of the dandy’s life, and a huge block of wood wedged in.

Please don’t think I am exaggerating when I tell you that I have seen an empty jam-pot carried in the lobe of the ear, the ear itself having grown right-round the impossible “ decoration ” ! The wearer of this last was considered an enormous swell. Then again, through the top of the ear are stuck several spikes of wood. Armlets and bracelets of wire twisted round to a depth of 4inch or 5inch complete an all-too-scanty visiting dress.

Of course one is called upon to entertain these visitors, and equally of course this entertaining takes the form of astonishing the native with the wonders of the white man. My next two snap-shots show how this is done in our far- away homestead. In the above photo, you will see a Swahili headman, all in white, bending over a good-sized musical-box, whilst on his left is an old chief with an expression of benignant resignation. He was formerly the greatest scoundrel for hundreds of miles round a perfect terror, in fact, defying even the white man’s power. He is positively covered with scars, obtained in fights with his neighbours far and near. However, he is on visiting terms with me now, and he likes to squat down near my musical-box and listen to the quaint thing playing white man’s music all on its own account.

An even greater wonder than the musical- box is the telephone, which I sometimes rig up in our garden, in order to introduce its marvels to the chiefs who drop in from time to time. Talking about our garden, I may mention that I found it absolutely necessary to in-close it with railings in order to protect it against our black neighbours’ sheep and goats, which contracted a disgusting habit of grazing upon our English vegetables. So you see we are troubled with neighbours even in this remote locality. In this garden we have English vegetables of all sorts— peas, beans, lettuces, beetroot, cabbages, tomatoes, etc. Naturally, then, on sitting down to a dinner of roast duck, shot "in the swamp close by, it is easy to forget that we are in the heart of Darkest Africa, particularly when that same duck is garnished with green peas and apple sauce—the latter tinned, unfortunately. All other provisions — tea, coffee, sugar, flour, salt, and other household commodities—have to be brought up-country from Mombasa. Formerly this was a long and tedious business, but now every day it becomes easier through the rapid progress made by the railway. Our letters, too, which a couple of years ago took a month to reach us from the coast, now arrive in three days.

Our house is comfortable enough, but of course it has its drawbacks, and it suffers, as everything does in this country, from the ravages of the all-devouring white ants. Houses of any kind only last a few years in this part of the world owing to these destructive insects. A typical native house is shown in the next photograph, and in front of it you will see some native ladies taking afternoon tea quite in the best European style. It may not really be tea they are drinking, mind you, but still the idea is the same, and it shows you that other civilizing institutions are progressing in Kikuyu beside the Uganda Railway.

These villages are usually built in thickly-wooded spots, and the houses are made of planks of cedar 4ft. high and 2ft. broad, placed lengthwise so as to form a circular, beehive shaped dwelling whose entrance is simply a hole formed by the omission of a couple of planks.

Of course, the women do most of the work in these villages, and the accompanying snapshot shows a woman of Kikuyu grinding native seed. She is not a prepossessing person, but still she looks robust enough for the work. The system is something like this: a hole is dug to form a basin or mortar in the trunk of a fallen tree, and then the seed is beaten with a long, heavy pole.

There can be no doubt that the natives of these parts are beginning to “know things”. There passed my door the other day a young Wa - Ki -kuyu, dressed up in the war attire of a Masai brave. As he passed I called out to him and asked him to wait a moment while I “ snapped ” him with my camera “ Yes, if you’ll pay me,” was his indignant reply; and I was obliged to retire within discomfited, marvelling exceedingly at the advance of civilization in these parts.

By way of recompense I dressed up one of our own servants—who looks obviously ill at ease with that spear— and painted nice greetings and things on his shield. I thought in this guise he might carry some pretty little message from these wilds out into the “ Wide World.”

My Housekeeping Troubles in East Africa.

BY MRS. FRED SNOWDEN, RAILHEAD, KIKUYU, BRITISH EAST AFRICA.

In this paper Mrs. Snowden tells us all about her domestic affairs in the wilds of Kikuyu.

How she beautified her mud-hut ; the mysterious tragedy of the bottles of port ; training Sa*ages as servants; famine experiences; queer pets, etc. With photos, by herself.

The lady here seen seated between two large tusks of ivory is Mrs. Fred. Snowden, of Railhead (Uganda Railway), Kikuyu, East Equatorial Africa. This lady wrote

a most interesting article entitled “ How I Keep House in Kikuyu,” On the right of the snap-shot is seen the old M’Kikuyu chief, whom we saw in the article listening to Mrs. Snowden’s musical-box,

outside the bungalow.

He has given an enormous amount of trouble to the Government. Standing up on the left is one of Mrs. Snowden’s house boys, and at his feet a little M’Kikuyu girl, employed to take care of the fowls.

Mrs. Snowden’s experiences of housekeeping are exceedingly interesting, including shopping by barter; untamed and un-clothed sa*ages for servants; and lions and warrior chiefs as afternoon visitors.

And yet this brave and bright English lady contrives not only to keep up her spirits in this remote region of Central Africa, but to “astonish the natives” with musical-boxes, telephones, and other

wonders of the white man.

The house is the most important item of our belongings in Kikuyu, for till quite lately so few of us had one. Still, so far as I am concerned personally, I

like living under canvas. It is one long picnic in a tent, or rather two tents, one for feeding and another for sleeping, with sundry grass huts around for the boys, goats, and chickens.

This, of course, providing it is a nice grass camp. On the other hand, a hut is preferable in a bushy district with no grass I am giving you an interior view of one side of our hut.

Its walls are of mud and the roof of grass. To make its appearance less “ muddy ” I sewed lengths of white calico to form a sort of hanging wall “paper” and suspended the stuff from the top, leaving

a space of about 3.5ft. below, thus forming a “ dado ” as it were. The utility of my calico hanging can be seen, since I was able to pin pictures around the room. The large coloured picture of the

Queen, or “ Bibi mkubwa ” (Great Lady), as the natives call her, was of great interest to them. For the first few weeks after I pinned it up I had daily visitors from all parts to see it.

It was amusing to watch a party gazing in admiration, and asking me questions as to what she did, how many villages she possessed, and if her chief had any other wives besides herself. Their idea of

greatness is the number of villages, wives, and cattle a person possesses. What appealed to them most was the fact that she wore a necklace and bracelets like them; they were highly delighted at

this.

To the right of the picture can be seen a dark spot; this represents a bunch of keys hung on a nail to lock our boxes and the storehouse. I had well tested the honesty of our house-boys, but never

found them tripping in the smallest way, not even with regard to sugar salt, or butter—commodities that the best-intentioned bla*k cannot resist.

So the keys were kept there to be always handy. One day, however, I had a shock; I required some wine from the store, and went to a box which had been opened two days previously when we took

out one bottle. Going to the case I picked up an empty bottle-straw, and another, and another, till they numbered nine, all empty! I thought the things must be bewitched. I called the two house-boys

and asked them for the full case of wine, and they said, “You are unpacking it now.” When I showed them the empty straws they were equally sur-prised. The mystery had to be cleared up, of course, and

all the camp was called to “ fall in.”

No one knew anything about it. The only step nearer was that the cook (note, the cook) went into the bushes and brought back empty wine, brandy, and other bottles. I then thought it was time to take

stock and find what else was missing. The result was that everything spirituous was short. How long this pilfering had been going on it was impossible to know—the only thing proven was that nine

bottles of port had gone in less than four days. This, too, had been ordered from England specially, as a “ medical comfort for me.

The solution of the mystery became more difficult as inquiries were made. The cook vowed he had seen the two boys drinking at night in their huts. They asserted their innocence, however, in such a

manner that it was hard to dis-believe them. At last, all our retinue being in disgrace, and things being, generally uncomfortable,, with a threat, that everyone: would be fined a month’s pay unless

matters were cleared up, the cooked confessed and gave up his modus operandi.

Early in the morning, about four o’clock, he used to get in by a wooden shutter, not very securely fastened, take the keys from the nail, and open the store,

in conjunction with the corporal of the guard, who used to keep the road clear when he changed the sentry. And I bad been flattering myself on having such a good early-riser ; the bread always baked

before breakfast, and chickens and other things cleaned and ready for use !

Men were deceivers ever! I could hardly believe him, even when he said he had done it, as he had been so honest in his work. Cooking materials lasted him ever so long; whereas the general complaint

of others was that sugar, salt, sauces, butter, etc., went too quickly.

I asked him how it was he had so religiously avoided taking any of these commodities, and yet had been so dreadful in other, respects. He said he knew if he

stole things under his care it could be traced to him, but since he had no right to come into the sitting-room nor go to the store, he thought the house-boys, who had charge of both, would be blamed

and punished, not with-standing how much they might assert their innocence.

This does not say much for his opinion of the white man’s justice! After a fair trial by the district officer this “handy-man” was sentenced to three months’ hard labour. For a bottle of port may be the price of a life in the East African interior.

During the trial it came out that he and his friend drank port wine and brandy in tumbler-full, or, rather, in condensed milk tins, half a tin of port

wine being filled up with brandy. I was sorry to be obliged to part with him in such an ignominious manner. He was so good at his work, and yet when I selected him as cook he did not know the use of

a saucepan-lid, but was most anxious to be taught—he proved a very apt pupil.

Cooks of all sorts—good, bad, and indifferent —are to be had in the country. We first started up-country with a man having an excellent testimonial, and asking

40 rupees per month. On the way we wanted a cup of tea, which he made by boiling the tea-leaves; and when I asked if he had made some bread, the boys said, “He has made a ‘risasi ’” (a cannon-ball),

which it indeed proved to be. On looking round and finding he had burnt all the enamel off the saucepans cooking his rice I thought it was time he should return to the coast.

Experienced Indian cooks are to be had, but I preferred to take a raw recruit and train him in the (cooking) way he should go. Several things seemed very funny

to him, such as a meat pie —which he called “meat- under - bread ”— and roly-poly jam pudding, “ long pudding in gumpti” (calico). Brussels sprouts, of which we grew fine specimens in our garden, he

called “cabbages that have little children ”—(cabbage-y wa watoto) in contradistinction to a big cabbage.

These bla*ks are certainly very quick in finding a name for anything that is foreign to them. For instance, the patent “ spark-lets ” apparatus for making

one’s own mineral waters amused them very much, and they called it “chupa bunduki,” or the gun-bottle. Champagne is “dawa bunduki”—medicine like a gun; “ dawa,” as it was only in evidence at times of

sickness. A traction engine is a “ tinka-tinka,” from the “tink-tink” noise it makes when in motion. Others again call it “ kata-miti,” a cutter down of trees, as it clears everything in front of it.

A traction engine surprised them more than the railway, as it came upon them unawares- no way cleared, no cuttings made, nor rails laid down for it to run along.

They were made aware of the train by seeing the preparations and having the thing explained to them, but not so with the “ tinka- tinka.” One old chief

followed it to a swamp where it was to be watered, and he sat for two hours in mute astonishment, and then remarked, “ What a big stomach it must have, to drink such a lot.” Speaking of the “

cabbages that have little children ” reminds me of my chickens and garden, and that takes me on to speak of the famine in Kikuyu.

I had a large number of chickens, and these soon cultivated a taste for English vegetables. The question soon was: “ Chickens and no garden, or garden and no chickens ? ” I am not greedy, still I

wanted both; so to get out of the difficulty I selected a starveling girl from amongst the hundreds of human beings who came daily to be fed, and told her that if she remained- in the garden to

“shish ” the chickens from early morning till sunset she should be well fed. In the photo, with the house-boy and the tusks the little one shows what she was like after being with us a

fortnight.

One day I had a narrow escape from being trampled on to one of my own cooking fires. The crowd went en- masse for the cauldron before I had given the word and

cleared out of the way, those behind pushing those in front. It was only by great exertion, and by calling to the sentry on guard, that the crowd was divided and I was extricated. After this I

arranged all the babies—mere skeletons—in circles of ten ; then the older children ; and, lastly, the women and men.

Then I doled the hot food out to them, a huge heap for each circle. It was pitiable to see their eagerness. I never wish to undertake the distribution of famine relief food

again.

One morning the headman, a Swahili, and a more came than usually intelligent black, speaking several languages and able to read and write English without a

fault, came to me and said I must not go into the crowd, as a poor starving youth had come covered with small-pox, and must be got away first. You see the headman in the photo, with three wives and

two children. His domestic establishment, by the way, was not one of peace, and the ladies often came to me with their grievances—it was a sort of divorce-court hearing, on a small scale.

The one sitting behind him eventually left him, saying she “ would have no more of it.” We all know of the jigger; in Kikuyu it is ubiquitous. Many of the Wa-Kikuyu have lost their toes through

neglecting the attacks of this noxious little insect My animal pets took some time to feed and attend to. Besides my faithful old dog “Pig ” there were pigeons, a parrot, a large cat, and several

monkeys. But the year 1900 did not seem a lucky one for me. In the early weeks of it all my pets came to grief.

My cat was carried off by a leopard; the parrot was torn to pieces by a wild cat; the monkeys died, and my chicken-house had nightly visits from either leopard or mongoose. In one week I lost eleven

beautiful hens The next photograph shows a tame lion cub we had about eighteen months ago. It was caught near the Athi River, not far from Machakos, some 260 miles from Mombasa.

It was kept for some time by the district officer of Kitui, and he, thinking it was getting too big to be a safe pet, sent it down to us, asking my husband if he would see to its safe transport to

the coast, as we were soon going on leave. It was never chained up, but allowed to roam was to see the cook (the man in the picture) prepare its food, with the cub lying between his legs during the

operation, and never attempting to touch the carcass, whereas the dogs and fowls were busily engaged scavenging around him.

At this time Mtoto, to which name the cub about the house and grounds like an ordinary cat. Our other pets then were a tame wild cat, an ape, an English

fox-terrier, and a black-and-tan with four puppies. The lion cub romped and played with these at will. Its food consisted of a goat, properly killed, cleaned, and boiled, daily. A novel sight

answered, was about five months old.

We took him to Mombasa, the first part of the journey by bullock-cart, and the latter by train. This same Mtoto can be seen in the Victoria Gardens at Zanzibar. He was presented to the Sultan, who

had a huge cage for him on the quay near his palace. But one day the cub was extra frolicsome, jumping up as the Sultan’s carriage was coming out of the gates, frightening the horses. He was then

moved to the gardens.

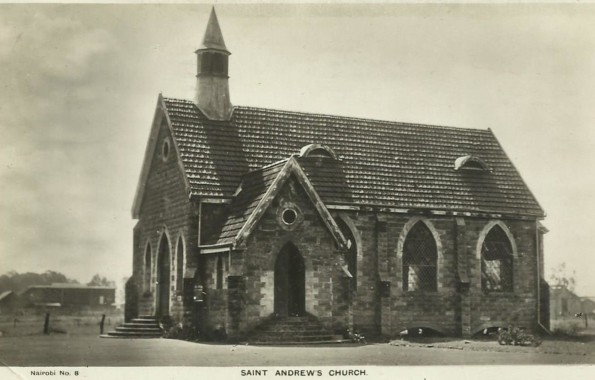

Click below for St Andrew's Church, Nairobi

![THE HOUSE-BOY WITH A PAIR OF TUSKS AND (ON THE LEFT)] THE POOR LITTLE CHICKEN “SHISH ”-ER WHOM MRS. SNOWDEN RESCUED From a Photo.] FROM STARVATION. [by the Authoress.](http://www.friendsofmombasa.com/s/cc_images/thumb_80733499.jpg)