The Luo People

The Luo are several ethnically and linguistically related Nilotic ethnic groups in Africa that inhabit an area ranging from South Sudan and Ethiopia, through Northern Uganda and eastern Congo (DRC), into western Kenya, and the Mara Region of Tanzania. Their Luo languages belong to the Nilotic group and as such form part of the larger Eastern Sudanic family.

Luo groups in South Sudan include the Shilluk, Anuak, Pari, Acholi, Balanda Boor, Thuri, Maban, and Luo of Dimo, and those in Uganda include the Alur, Padhola, and Joluo.

The Joluo and their language Dholuo are also known as the "Luo proper", being eponymous of the larger group. The level of historical separation between these groups is estimated at about eight centuries. Dispersion from the Nilotic homeland in South Sudan was presumably triggered by the turmoils of the Muslim conquest of Sudan.[citation needed] The migration of individual groups over the last few centuries can to some extent be traced in the respective group's oral history.

The Luo (also Lwo) are part of the Nilotic group of people. The Nilote had separated from the other members of the East Sudanic family by about the 3rd millennium BC. Within Nilotic, Luo forms part of the Western group.

Within Luo, a Northern and a Southern group is distinguished. "Luo proper" or Dholuo is part of the Southern Luo group. Northern Luo is mostly spoken in South Sudan, while Southern Luo groups migrated south from the Bahr el Ghazal area in the early centuries of the second millennium AD (about eight hundred years ago).

A further division within the Northern Luo is recorded in a "widespread tradition" in Luo oral history: the foundational figure of the Shilluk (or Chollo) nation was a chief named Nyikango, dated to about the mid-15th century. After a quarrel with his brother, he moved northward along the Nile and established a feudal society. The Pari people descend from the group that rejected Nyikango.

The Anuak are a Luo people whose villages are scattered along the banks and rivers of the southwestern area of Ethiopia, with others living directly across the border in South Sudan. The name of this people is also spelled Anyuak, Agnwak, and Anywaa. The Anuak of South Sudan live in a grassy region that is flat and virtually treeless. During the rainy season, this area floods, so that much of it becomes swampland with various channels of deep water running through it.

The Anuak who live in the lowlands of Gambela are distinguished by the color of their skin and are considered to be black Africans. The Ethiopian peoples of the highlands are of different ethnicities, and identify by lighter skin color. The Anuak have accused the current Ethiopian government and dominant highlands people of committing genocide against them. The government's oppression has affected the Anuak's access to education, health care and other basic services, as well as limiting opportunities for development of the area.

The Acholi, another Luo people in South Sudan, occupy what is now called Magwi County in Eastern Equatorial State. They border the Uganda Acoli of Northern Uganda. The South Sudan Acholi numbered about 10,000 on the 2008 population Census.

Around 1500, a small group of Luo known as the Biito-Luo, led by Chief Labongo (his full title became Isingoma Labongo Rukidi, also known as Mpuga Rukidi), encountered Bantu-speaking peoples living in the area of Bunyoro. These Luo settled with the Bantu and established the Babiito dynasty, replacing the Bachwezi dynasty of the Empire of Kitara. According to Bunyoro legend, Labongo, the first in the line of the Babiito kings of Bunyoro-Kitara, was the twin brother of Kato Kimera, the first king of Buganda. These Luo were assimilated by the Bantu, and they lost their language and culture.

Later in the 16th century, other Luo-speaking people moved to the area that encompasses present day South Sudan, Northern Uganda and North-Eastern Congo (DRC) – forming the Alur, Jonam and Acholi. Conflicts developed when they encountered the Lango, who had been living in the area north of Lake Kyoga. The Lango also speak a Luo language. According to Driberg (1923), the Lango reached the eastern province of Uganda (Otuke Hills), having traveled southeasterly from the Shilluk area. The Lango language is similar to the Shilluk language. There is not consensus as to whether the Lango share ancestry with the Luo (with whom they share a common language), or if they have closer ethnic kinship with their easterly Ateker neighbours, with whom they share many cultural traits.

Between the middle of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century, some Luo groups proceeded eastwards. One group called Padhola (or Jopadhola - people of Adhola), led by a chief called Adhola, settled in Budama in Eastern Uganda. They settled in a thickly forested area as a defence against attacks from Bantu neighbours who had already settled there. This self-imposed isolation helped them maintain their language and culture amidst Bantu and Ateker communities.

Those who went further a field were the Joka Jok and Joka Owiny. The Jok Luo moved deeper into the Kaviirondo Gulf; their descendants are the present-day Jo Kisumo and Jo Rachuonyo amongst others. Jo Owiny occupied an area near Got Ramogi or Ramogi hill in Alego of Siaya district. The Owiny's ruins are still identifiable to this day at Bungu Owiny near Lake Kanyaboli.

The other notable Luo group is the Omolo Luo who inhabited Ugenya and Gem areas of Siaya district. The last immigrants were the Jo Kager, who are related to the Omollo Luo. Their leader Ochieng Waljak Ger used his advanced military skill to drive away the Omiya or Bantu groups, who were then living in present-day Ugenya around 1750AD.

Between about 1500 and 1800, other Luo groups crossed into present-day Kenya and eventually into present-day Tanzania. They inhabited the area on the banks of Lake Victoria. According to the Joluo, a warrior chief named Ramogi Ajwang led them into present-day Kenya about 500 years ago.

As in Uganda, some non-Luo people in Kenya have adopted Luo languages. A majority of the Bantu Suba people in Kenya speak Dholuo as a first language and have largely been assimilated.

The Luo in Kenya, who call themselves Joluo (aka Jaluo, "people of Luo"), are the third largest community in Kenya after the Kikuyu, and Luhya. In 2010 their population was estimated to be 4.1million. In Tanzania they numbered (in 2001) an estimated 980,000.

The Luo in Kenya and Tanzania call their language Dholuo, which is mutually intelligible (to varying degrees) with the languages of the Lango, Kumam and Padhola of Uganda, Acoli of Uganda and South Sudan and Alur of Uganda and Congo.

The Luo (or Joluo) are traditional fishermen and practice fishing as their main economic activity. Other cultural activities included wrestling (yii or dhao) kwath for the young boys aged 13–18 in their age sets. Their main rivals in the 18th century were luo Lango, the Highland Nilotes, who traditionally engaged them in fierce bloody battles, most of which emanated from the stealing of their livestock.

The Luo people of Kenya are nilotes and are related to the Nilotic people. The Luo people of Kenya are the fourth largest community in Kenya after the Kikuyu, Kenya, and, together with their brethren in Tanzania, comprise the second largest single ethnic group in East Africa.

This includes peoples who share Luo ancestry and/or speak a Luo language.

Acoli (Uganda and Kenya)

Acholi (South Sudan and Uganda)

Alur (Uganda and DRC)

Anuak (Ethiopia and South Sudan)

Blanda Boore (South Sudan)

Gambella (Ethiopia)

Jopadhola (Uganda)

Jonam (Uganda)

Jumjum (South Sudan)

Jurbel (South Sudan)

Kumam (Uganda)

Joluo (Kenya and Tanzania)

Luo of Dimo (South Sudan)

Pari (South Sudan)

Shilluk (South Sudan)

Thuri (South Sudan)

Maban (South Sudan)

Balanda Bwoor (South Sudan)

Cope/Paluo people (Uganda)

source: http://www.alphaigogo.com

Our ancestors never believed in the existence of man as potrayed by science or religion. They had their own myths and legends to account for their origin.

According to an account given by Chief Gor Mahia K'Ogallo of Kanyamwa to Charles Hobley the first administrator of Kavirondo,Apodho was the father of all mankind, and he appeared on earth together with the sun, the wind, and the moon.He brought with him to earth a spear, a shield and fire.

Buffaloes, and the cattle came out of the sea, probably Lake Victoria, and were hearded by mankind.But one day the buffalo broke away, and took to the forest refusing to become tame like the cattle.

Gor Mahia went on to narrate that, shortly after Apodho's arrival on earth, he ordered the moon to kill an ox, but the moon refused. He then told the sun and then the wind, but they also refused. So he killed the ox himself with a blow from his fist.

Thereafter, he offered some meat to the sun, the wind and the moon but they all refused to eat. Sensing Apodho's anger, the moon, the sun, and the wind fled back to the heavens where they have stayed ever since.

Apodho always told his children that he had left a beautiful country in heaven where people were all bright like fire, and that when they died, they would all go and meet these bright people.

According to Gor Mahia, Mbuga the eldest son of Ramogi, was the first member of Luo tribe to migrate southward into Kavirondo(Nyanza) followed by his brothers. Upon arrival they found the Kavirondo Bantus had occupied the whole land, but they gradually drove them back.

K'Ogallo also explained that the Bantus of Nyanza were descendants of a person called Mugirango while the Masai's were descendants of one young Luo man who strayed away.

The young man had been sent to herd cattle, but absconded and disappeared into the forest. One woman crept away and joined him, and together they became progenitors of the Masai. He gave this as a reason why the Masai eat herbs and drink milk to this day.

On the Nandi and the Kipsigis, he explained that they were descendants of Alang'o the son of Ramogi (Luo ancestor, who was also the grandson of Apodho). It was Ramogi, who taught the Luos the custom of mixing cow's urine with the milk, according to Gor Mahia.

All other people on earth including Europeans were descendants of Rajwogi.

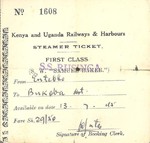

Mile 581, 19th Dec 1901 reached the shores of Ugowe Bay (Lake Victoria). That is Florence Preston's wife, the foreman plater at the railhead Roland Preston drove home the final key of the railway.

Port Florence (Kisumu) was named after Chief Engineer Mr Whitehouse's wife, but it was Ronald’s wife Florence Preston who was photographed ‘driving the last spike’ on the shore of Lake Victoria.

Port Florence had been renamed Kisumu (a name derived from the Luo word ‘sumo’ meaning the place of barter trade).

The railway line was finished in December 1901 as the sun was making its descent on the town of Kisumu. To commemorate the end of construction, Mrs. Ronald Preston, wife of the plate laying engineer, drove the final steel key into the rail.

In an interesting twist, the chief engineer’s wife Mrs. Whitehouse and Mrs. Preston had identical first names, Florence. “Port Florence was named after the Chief Engineer’s wife Florence Whitehouse, but it was Ronald’s wife Florence Preston who was photographed ‘driving the last spike’ on the shore of Lake Victoria…” Preston himself inscribed in his book, Oriental Nairobi. Because of the photo, most accounts say the town was named after Mrs. Preston.

The confusion was later resolved when the name was changed to Kisumu – Port Florence was found, somewhat inconsiderately, unworthy of the locale by Special Commissioner of Uganda, Sir Harry Johnson. In a letter, he succinctly wrote “If the native name of the place be laid aside, the European name to be chosen should be of some member of the British royal family or of some great explorer associated with the discovery of Lake Victoria, Nyanza.

” All told, it took five years to complete the railway line and it would take another three decades before it was completely extended to Kampala. And while that seems like a long time – consider that the American Transcontinental Railroad took just six years – what’s truly impressive about East Africa’s line is that it wasn’t building just a railway.

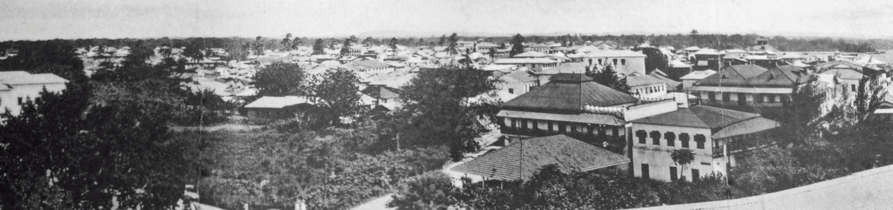

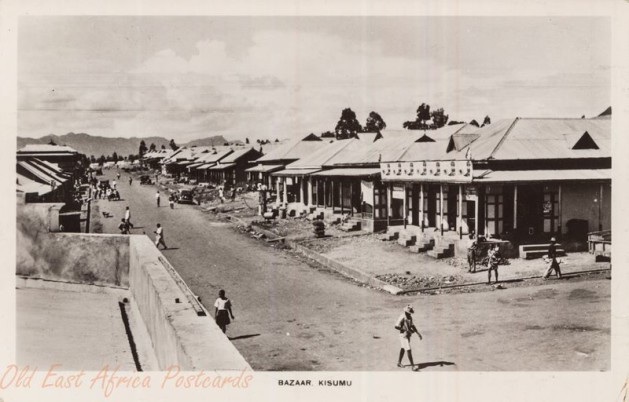

Kisumu Township 1919

Kisumu Township in 1919. The photo was taken from the direction of Mosque Rd in the CBD near the present day Kenton Square. In the background are the railway hill and the lake. Hobley wrote that Kisumu town was full of small rocks which took him time to clear.

Kisumu in 100 Years: An incredible journey in pictures

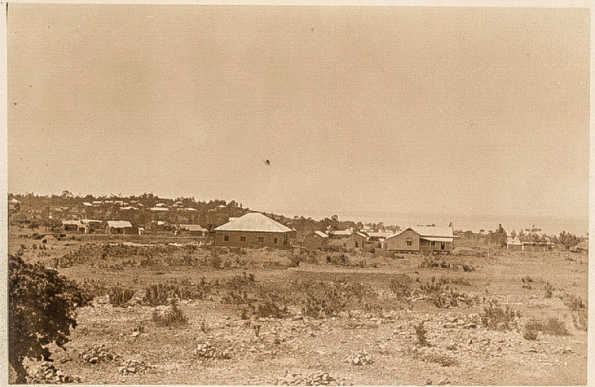

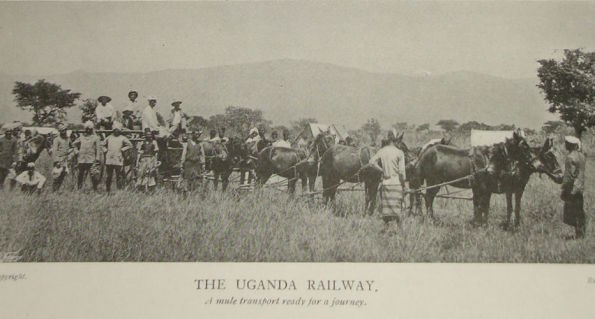

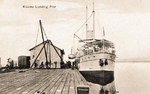

The Transportation of Uganda

The line of railway running between Mombasa and the Victoria Nyanza, many changes may be expected to be made in the conditions of life hitherto prevailing in British East Africa and Uganda. Until the engineering work had so far progressed that the locomotive could run to the lake, mule transport had to be employed; but now that the shriek of a locomotive is heard on the shores of the Nyanza. this has been superseded by steam. One of the pictures we publish today shows a number of these mule teams, which have been sold as remounts, and they are now on their way to South Africa, if they have not already arrived there.

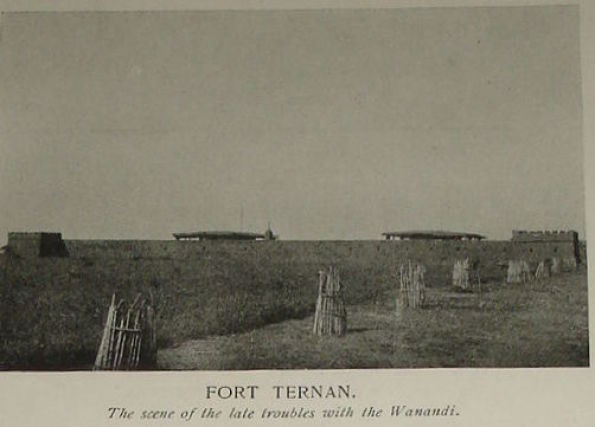

Sir Harry Johnstone has spoken of the Uganda Railway as a wedge of India driven into Africa. Indian labour has been well to the fore in the construction of the line, for the natives in many cases have proved too lazy to work. Round some of the railway centres, and in Uganda itself, the Indian trader has firmly established himself. The other illustration is a snap-shot of Fort Ternan, called after Colonel Ternan, formerly Commandant and Acting Commissioner in the Uganda Protectorate, but who has since done distinguished service in South Africa. In the vicinity of this fort, with its memories of rights with the Nandi people, is now a railway station. This point is reached. 540 miles from the coast, shortly after crossing the Mau escarpment at an altitude of between 5.000-ft. and 6.000-ft. Fifty miles further in the interior is the lake shore, where the line drops to 3,700-ft.

It will probably be some little while before the Uganda Railway is formally opened, for thoughts trains run regularly in each direction, there still remains much heavy engineering work to be done. T e m p o r a r y structures have to be replaced, and temporary deviations turned into the permanent way. It is estimated that quite a year will elapse before the construction of bridges, etc., is completed.

A consular report just issued states that two fair-sized

steamers are now under construction for working the traffic from the centre of Uganda across Lake Victoria to Port Florence, the terminus of the railway. The journey across the lake takes two days, and the steamer runs so as to connect with the train. On reaching the eastern shore of the lake passengers land from the steamer in boats and lighters, and make their way to the station, which is some two miles distant. In most cases the train is waiting, and passengers can sleep in the carriages. At present passengers have to provide their own tents, etc, but a bungalow is in course of construction, which will serve to accommodate all waiting passengers till the train arrives. The journey to Mombasa usually occupies three days, and the arrangements for refreshments are at present somewhat primitive.

LAKE REGION CONTINUED

The first Railway to Uganda

Churchill’s trip to Kenya /Uganda 1907

Two days after I had arrived at Entebbe the Governor took me over to Kampala. The distance between the ancient and the administrative capital is about twenty-four miles. The road, although un-metalled, runs over such firm, smooth sandstone, almost polished by the rains, that, except in a few places, it would carry a motor-car well, and a bicycle is an excellent means of progression. The Uganda Government motor-cars, which are now running well and regularly, had not then, however, arrived, and the usual method was to travel by rickshaw. Mounted in this light bicycle-wheeled carriage, drawn by one man between the shafts and pushed by three more from behind, we were able to make rather more than six miles an hour in very comfortable style. Continued.........

Click Below

The photo of Kisumu Post Office in

1909.

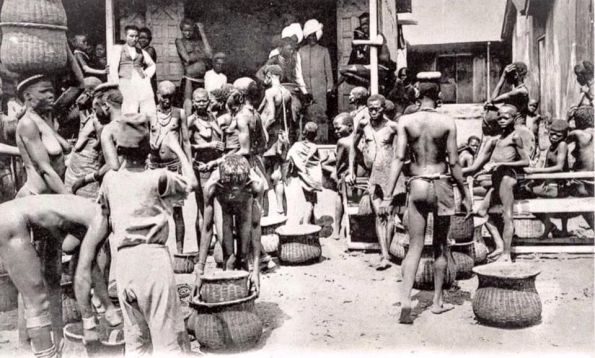

Before Retired US president Theodore Roosevelt visited the town in Dec 1909, he was requested to visit Kisumu native market during his tour,since he would find it interesting to watch" hundreds of

naked men and women engaged in barter trade."

"The foodstuffs at the market are not always of the best and at times the odors are almost unbearable," he was advised .

He was ,however, warned of Kisumu's two curses "the sleeping sickness and the bubonic plague."

The Town of Kisumu ...Life Ashore 1914-1945..L.G "Bill" Dennis "The Lake Steamers of East Africa"

From the first steps described in an earlier chapter the town of Kisumu emerged. One of the many subjects touched on in the Hammond Report was the 'temporary' nature of the buildings throughout the system: "Wood and iron buildings were, no doubt, used in the original construction to keep the capital cost as low as possible, but no provision has been made to finance their replacement.. .The life of a wood and iron building in East Africa may be fairly put at twenty years ... it is false economy to keep patching them up."

The sketched impression of Kisumu is from memory and assistance from June McGregor. The curved roads, perhaps following the contours, represent the early paths through Railway land and the

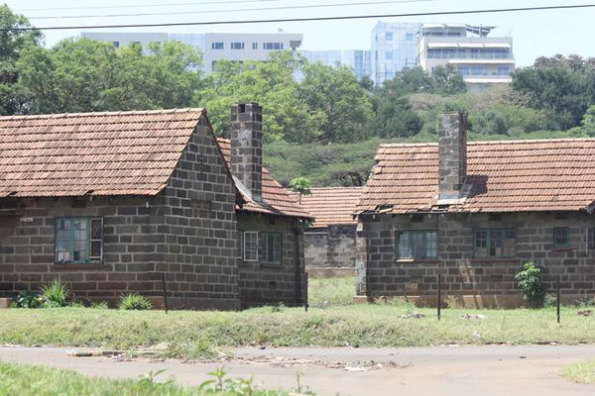

blank blocks indicate the early houses. Those on the higher ground along what became Church Road were also of early construction.

The photograph below (page 127) is of the largest house on Church Road, built in those early years and traditionally the home of the Senior or Superintendent Marine Engineer, the most senior Marine, and Railway, officer based in this town. It housed an unbroken line of S.M.E.s until vacated by T. C. (Tommy) Tippin. Your author was the first 'deck man' to occupy it and the Vauxhall Velox at the door will date the photograph around 1960. Ian McGregor was the incumbent until 1970 - so the wood and iron structure had been patched up for something over fifty years.

With polished wood floors, a wide and airy verandah enclosed in mosquito proof mesh, it had to be a very furious thunderstorm that forced the closure of the inside windows. In the early days there was no electricity and lighting was by paraffin lamps, the Tilley pressure type giving a stronger and wider illumination. Without refrigerators, food was stored in wire meshed meat safes, the legs of which stood in cans of water, with a film of paraffin to discourage the ants. The servants' quarters and kitchen, with wood-burning stove, were at the rear and reached by a covered walkway. Also, to the rear were fruit trees producing Avocados, Paw-Paws and Mangoes: in the case of the latter the fruit always disappeared as it became ripe!

Those houses built along the contoured roads all had numbers under twenty, while those on Church Road could have been in the thirties.

The house depicted overleaf was also on Church Road and marginally younger than the previous one, the photograph was taken in the late 'fifties. The lop-sided box beneath the left hand tree held the water cock indicating that mains water was 'on tap'.

Within a short time electricity for lighting became available for limited hours of darkness from a very limited supply. Some people, wishing, perhaps to do their own cooking, purchased paraffin burning stoves, but the African 'M'pichi' was more at home with the wood-burning Dover stove - particularly if a Shamba Boy was at hand to maintain a supply of 'Kuni' (firewood). Besides, the wood-burner ensured a good supply of hot water for the bath - no showers in those days.

A commercial and shopping area for Europeans slowly took shape on a road at the top end of the contoured area; now called Oginga Odinga Road, it runs northward from the site of the hotel shown on the sketch map. Further down and facing the Railway track, the Asian Bazaar and early Asian dwellings took root.

Early occupants of the main street were the provision stores, Londiani Stores and Morgan & Wood. The latter was taken over by Indian proprietors after some years but was still trading under that name in 1991. Jan Mohamed set up his tailoring business, and at the time of the nearby Kakamega 'gold-rush' in the early 'thirties John Riddoch and others sought to supply the prospectors with their requirements. The Post Office was established close to the site of the present Central Square, while the Nyanza Printing Works, Gailey and Roberts and Eric Hall's Chemist shop were later additions. 'Jimmy' Maxwell built the Hotel where Nick Slobin was the manager for countless years.

Very soon after the first war, a touch of romance was brought to the town, fittingly the hero of our early story, Richard Grant, was one of the two main players, and the following has been contributed by Ian Grant, one of my mentors in the production of this record:

Kell/Grant Family Connections.

Captain Philip Kell was appointed master of the S.S.

Clement Hill on commissioning of that vessel for the

Uganda Railway Marine in March 1907.

BACKGROUND OF KISUMU CITY

https://kisumucitycouncil.wordpress.com/2012/10/25/background-of-kisumu-city/

MEMORIES OF KISUMU

By W. ROBERT FORAN “A little one-eyed, blinking sort o' place."

Thos. Hardy : Tess of the D'Urbervilles.

KISUMU, then known as Port Florence, was born

at the turn of this century. Like Nairobi, it was a child of the Uganda Railway. The railhead reached it on the shore of Usoga Bay in the Kavirondo Gulf of Lake Victoria on December 20, 1901. But

even before then there had been established shipbuilding yards and the launch Mackinnon, after its various component parts had been carried by porters from the

coast, was rebuilt and launched from those shipbuilding yards. This was a Homeric performance, indeed!

The Clement Hill, Winifred, Sybil and Nyanza—their parts conveyed on the new railway from Mombasa to Kisumu—were re-constructed

and launched there not long afterwards.

Vastly different

The place was destined to become the headquarters of the Kisumu (now Nyanza) Province. Until April 1, 1902, what are now the

Nyanza and Rift Valley Provinces were part of the Uganda Protectorate, and had been so from 1893 when the Foreign Office proclaimed a Protectorate over Uganda and British East Africa. The

headquarters of the Assistant Commissioner were at Eldama Ravine. The headquarters of the Nyanza Province were sited at Kisumu and that of the Naivasha Province at Naivasha on April 1, 1902, each

being under its own Provincial Commissioner.

The Uganda Railway Police became amalgamated with the newly formed B.E.A. Police in the middle of 1904, and for some years to follow there ceased to be an individual Railway Police Force. Having joined the new B.E.A. Police on May 15, 1904, and posted in charge of the Nairobi police station, I was transferred to Kisumu on October 15 of that year. Thus, my memories of the early stages of Kisumu go back for nearly 55 years.

The Town is a vastly different place to what it appeared between 1904 and 1929; and when there last in 1953 it was almost

impossible to credit the evidence of my eyes. From a small, crude and pioneer town “out in the blue” it had been immensely developed, improved and enlarged until its citizens can proudly echo the

words of Rudyard Kipling’s The Seven Seas: “Of no mean city am I”! Indeed, the passage of the years has made Kisumu a large, important and prosperous centre in Kenya

Colony.

In October, 1904, when I first arrived there it was no more than a shanty village of mushroom growth; and Hardy’s lines aptly

describe how it struck me at first sight. The years that followed did little enough to cause a revision of my first impressions. No hotel existed: only the Railway’s Dak bungalow on the shore of the

lake behind the railway station.

The railway station was of corrugated iron with a single platform, unroofed and open to the powerful sun’s glare, and sited close

to the shore of the lake not far from the Indian bazaar and pier for the lake steamers to berth alongside. It has since been replaced by a much better building and roofed platform. The Dak bangalow

still existed in 1929, but later was demolished as it had become redundant after the Kisumu Hotel was built to accommodate casual visitors or those arriving and departing by the lake

steamers.

Single street

The Indian bazaar had a single street lined by iron shanties on either side, where the Indian traders carried on business. I

doubt if there were more than 20 dukas then; but in 1956 the Asian population totalled between 10,000 and 10,500. Trade was mostly with the Kavirondo (now Luo) people. They—men, women and children—

were nudists and still so when I passed through in 1929.

Close to the Indian bazaar, but beyond the police station and beside the open-air market-place, was the wood-and-iron home and

trading-store of P. H. Clarke, the only European business at Kisumu. His partner was A. K. Milliken. This partnership was dissolved shortly afterwards; and then Clarke was joined by a nephew, F. H.

Clarke, who was later with the Game Department and is now farming near Nakuru- Still later P. H. Clarke acquired the flourishing business of Boustead Brothers, owners of the Mombasa Club, at Mombasa

and changed the name of the firm to Boustead and Clarke.

Clarke and Milliken were energetic, popular with everyone, and richly deserved the degree of success in business attained by

them. From about 1902 to 1907 Clarke officiated as the Town Clerk of Kisumu, when succeeded by H. Hartley (later the famous author Talbot Munday in America) but he remained for a few months before

going off to India. Hartley was succeeded in 1907 by Francis Hayes-Corbet, who had served under me at Nairobi as a sergeant of the newly-formed European Mounted Police. P. H. Clarke died at Mombasa

in 1935. His name will always be remembered at Kisumu, for he did much to foster its early development.

In 1908, when all were present in Kisumu, the total European population never exceeded 20; and until 1905 all were bachelors, so no white woman was to be found there. The first was Mrs. Bruce, the bride of Chief Officer Bruce of the Winifred; and she was followed in 1907 by Mrs. Dolly Stedman, wife of J. H. H. Stedman, the Public Works Executive Engineer.

The then (1905) Provincial Commissioner, Stephen Salisbury Bagge, had decreed that Kisumu was far too unhealthy for married

officers, and women would only upset the small community’s peaceful life. The arrival of Mrs. Bruce aroused his ire. He stormily threatened to have them both transferred elsewhere, but I pointed out

that a sailor serving on a lake steamer must remain with his ship and could not be moved to a land job. He then accepted the situation with good grace.

The only sources of social gaiety and recreation available were the tennis courts and Nyanza Club—the latter built by the Uganda Railway for use of its officers. The Railway Institute, on the lake shore near the shipbuilding yards, had a sports ground where cricket was sometimes played, but the surface being like iron was not conducive to high scores. On such hard ground games of rugby, soccer or hockey were ruled out. Concerts and dances were always staged at the more spacious Railway Institute, but they were few and far between.

Cheerful spot

The Nyanza Club was a small, ungainly, corrugated-iron building containing but three rooms—a small library and reading-room, the

central portion a billiard room, and the other a card room. No other facilities existed. It was always a cheerful spot after sundown, the more so when one of the lake steamers happened to be in port.

The ships’ officers brought new life to the jaded nerves of residents and considerably enlivened things.

The Club had no bar. Each member kept his own supply of drinks in a locker, the keys being held by the Goanese steward. Soda water could be obtained on chits from the steward and accounts settled monthly by cheque, there being a great difficulty in procuring currency as no bank existed in Kisumu.

The engineer in charge of the shipbuilding yards was Richard Grant. He was a nephew of Captain J. A. Grant, the companion of

John Hanning Speke on his journeys to discover the source of the Nile in 1862. For a number of years he lived at Kisumu, built and launched ships, and carried out all repair or renovation work for

the Marine Service. The Resident Engineer of the Railway at Kisumu was Mr. Sydney Couper when I arrived in 1904; and he was still there when I was transferred to Mombasa a year

later.

Bubonic plague periodically occurred at Kisumu, and there was a severe outbreak of this disease in 1905 which caused many deaths among the Asian and African communities. Only by the most strenuous efforts was the outbreak conquered. The Medical Officer, Dr. J. A. Haran, imposed the strictest possible quarantine and the Police enforced this without fear or favour.

To inspect works

The daily average of deaths amounted to 30 Asians or Africans. All the dead were cremated or buried in rear of the prison on the Hill, and this site is now occupied by a large Asian residential estate. It was six weeks before the quarantine restrictions were eased.

The Manager of the Railway, Mr. H. A.

Currie, arrived by train from Nairobi to inspect some new works at the port and the African constable on duty at the pier gates

refused to let him pass through them in accordance with the quarantine regulations. Currie insisted. I was called and refused to permit it, warning him that if he went on the pier it would not be

possible to come out again until the quarantine period ended. In spite of this, he insisted on going through the gates to carry out his inspections.

I refused to let him pass through the gates to rejoin his train to Nairobi, and threatened to arrest him if he infringed

the quarantine rules. Dr. Haran kept him there for five days, while he was forced to live on a steamer alongside the pier until a blood test showed him to be free of

infection.

Although there is now a flourishing Yacht Club, in my time the only yacht was owned and sailed by Captain J. A. Gray, the

commander of the Sybil. If in 1908 the total European population was no more than 20, in 1956 it was estimated that it consisted of from 600 to 650; and it has steadily increased since

then.

Another scare at Kisumu in 1907 was an outbreak of smallpox on a lake steamer. Only one man of the crew had been stricken with the disease, but it was decided to quarantine Commander C. B. Blencowe, Chief Officer A. R. Vereker, and all members of the crew on an uninhabited island in the Kavirondo Gulf some miles from Kisumu.

Up to his neck

They were landed on the island with camping outfits, stores and ample provisions; also a stock of cattle, sheep, goats, fowls,

and a few cows in milk. They were supplied with a helio to communicate from this barren island with Kisumu. Crocodiles played havoc with the livestock. Then a careless African sailor ignited the

grass and all the grazing was destroyed.

Blencowe, wandering over the island, discovered a bees nest and fired his rifle into it to drive away the bees so that he could

harvest the honey. The angry bees pursued him to the water’s edge. He had to stand in the water up to his neck to escape their enraged attacks and risk being devoured by a crocodile. He was kept

there until sunset.

Next day he heliographed to Kisumu a report of their predicament, but the reply was a court order to remain on the island until

the quarantine period ended. For some months afterwards it was rash to mention bees or smallpox in the hearing of Blencowe or Vereker.

In mid-July, 1908, I went on long leave and did not return to East Africa until early April, 1909. I was then no longer an

officer of the B.E.A. Police but special correspondent of The Associated Press of America with ex-President Theodore Roosevelt’s African safari (1909-10). Three times in that year I passed through

Kisumu on my way to or from Uganda, and found the place but little changed for the better.

Of all the many stations in Kenya at which I was posted for duty from 1904 to 1908, I liked best the two years spent at Kisumu 1904-05 and 1907-08).

A Global History of Asian’s Presence In Kisumu District of Kenya’s Nyanza Province

Introduction

The idea of globalization and global history is not a recent phenomenon. As early as the first century, East African Coast had already started witnessing the emergence of traders from Asia especially the Chinese who brought porcelain and other trade items along the coast of East Africa. Towards the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, globalization took a new dimension due to imperialism and colonialism. These two processes opened up the world and more so East Africa to the rest of the world. The Africans were thus exposed to new forms of religion and their economy was opened up to the international market system and economy. These activities as well as slave trade laid the foundation upon which global history was to be written. In Kenya for instance, the colonial administration’s “encouragement” of trade was undertaken within a broad economic policy framework which assigned the different races in Kenya and fractions of merchant capital specific roles. Occupying the highest rank on the commercial ladder were European importers and exporters. Asians occupied a middle position while Africans formed the lowest chain in the marketing system. The colonial government also employed indirect and direct compulsion to “encourage” trade. For instance, in addition to raising revenue, the imposition of the hut tax early in 1902, was also intended to induce Africans to grow and sell surplus produce if they were to be able to meet the tax obligation.1 In such situations, Africans were compelled to engage in exchange of goods in Kisumu, Ndere, Yala and Kendu Bay with the Asians so as to raise money to pay for their tax.

https://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/329

From Punjab to the shores of Lake Victoria: The Kalasinga of Kisumu

Mascarenhas, the Abagusii named her "Omongina" when she arrived in Kenya in 1912

Even though her name was Mascarenhas, the Abagusii named her "Omongina" when she arrived in Kenya in 1912 and settled in the village of Riana where her

husband Thomas Joseph also from Goa india, operated a duka he had established in 1902.

Unfortunately , Omongina's joy of settling down with her new husband was short lived, for he died 10 years later (1922) at Riana after contracting Blackwater

fever,a complication of Malaria that killed many people around Lake Victoria. . They had just gotten a baby.

Widowed at the age of 29 in a remote part of Africa , with one year old baby, life wasn't rosy for Omongina the young Goan girl. Capt Richard Gethin (Snr),

who met her at Riana wrote:

" I was passing, a Goan woman came out of one of the shops and was very interested to know where I was going. She struck me as being very poor, as she was barefooted and badly dressed, but she very kindly asked me to come in and have a cup of tea, which I did. " However despite her situation, Omongina was still determined to continue with what her husband had started in the village of Riana.

While at Riana she discovered an opportunity that she wanted to capitalise on. Many people were starting to embrace Western style of dressing , and she

thought dressmaking would be a lucrative venture. However she didn't have enough capital to start the business.

Consequently she sold her four gold bangles to an Indian trader at Kisii , raised enough money and bought a ticket to India. While in India she sold her

assets, obtained the proceeds of her husband's insurance policy then made her way back to Riana Gusiiland via Mombasa.

"I bought and carried with me plenty of India cloth. With the help of my 'Singer' hand-sewing machine (bought for my wedding in 1910), I started dress making

for the Kisii and Luo women," she wrote. "Until then, they did not wear any Western clothing. Men wore loin cloth or goatskin flaps in

front and rear. Kisii women wore goat skins from the hip downwards.Luo women wore a sort of skirt made of papyrus or other reeds grown along the lakeshore. The Catholic Mission at Asumbi and

Nyabururu helped me tremendously by sending all the women to have them "dressed" by me"

As news of her dress making spread, so did the business boom. she expanded the business by selling the most sought after items like sugar, salt, soap,

kerosene oil, beads, cigarettes, matches and hoes.

She sold some of her wares at Homa Bay and Kisumu where she travelled by boat. It must have been tough for her to travel around with her baby.

In 1924, she bought a plot at Homa Bay and erected a rental structure at a cost of 4000/-.She rented it for 80/- a month. A year later, she bought another

plot, this time at Sare-Sakwa-Awendo for the same price, and again rented it out at 80/- per month.

Wanting to give her son Alex the best of education, she moved to Kisumu in 1927 and got Alex admitted at Indian Primary school which later became Government India School , and today, Kisumu Boys High School .

Initially she rented a house but later on bought a plot on De Boer Street in the Kisumu CBD, where she put up permanent buildings consisting of two shops and

four living rooms. She and Alex moved into the two rooms and rented the remaining two.

She later bought another plot for Shs. 5,500 on Station Road, in the present Kisumu CBD.

The most remarkable venture of this young widowed lady was the purchase of a 160 acre farm at Kibigori, which she bought from a soldier-settler.

" I sold a lot of wood fuel, extra cattle, some coffee and maize. Within two years, I recovered the purchase price I had paid for the farm. However, with the

depression at its height, and the prices of produce at rock bottom (a 200 lbs bag of maize for Shs 2/25), I started losing money; what I had gained in the first four years, I lost in the subsequent

five years, and eventually sold the farm in 1940 at a profit."

At the time of her death at Victoria Hospital Kisumu in 1963 at the age of 69, Omongina was the richest woman in Nyanza, a total contrast of the young widowed

lady struggling in Kisii.This could be attributed to a good business head, a forward vision of events and her shrewdness.

#The British Empire Chronicles

Credit and thanks to Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

East African Railways and Harbours, Marine Services

http://www.mccrow.org.uk/eastafrica/eastafricanrailways/marinedivision/earlakes.htm

A market scene at Port Florence (Kisumu) in the early 1900s

Kisumu city is believed to be one of the oldest settlements in Kenya. Historical records indicate that Kisumu has been dominated by diverse communities at different times long before Europeans arrived. The people from the Nandi, Kalenjin, Kisii, Maasai, Luo and Luhya communities converged at the tip of Lake Victoria and called the place "sumo" which literally means a place of barter trade. Each community called it different names, for instance:

The Luo called it "Kisumo" meaning "a place to look for food" such that the Luo would say "I am going Kisuma" to mean "I am going to look for food".

The Abaluhya called it "Abhasuma" which means "a place to borrow food" such that the luhya would say "I am going Khusuma" to mean "I am going to borrow food".

The Abagusii called it "egesumu" meaning "a structure for keeping/rearing chicken". It is believed the Abagusii were in Kisumu but found Kisumu was not good for crop husbandry and agriculture.

The Nandi called it "Kisumett" which means a place where food was found during times of scarcity and exchange, which cannot be attacked by Nandi and Terik irrespective of any issue.

Industries are centered on processing agricultural products, brewing, and textile manufacturing. Asians once constituted more than one-fourth of the population, but that segment declined after independence in 1963.

Kisumu was identified by the British explorers in early 1898 as an alternative railway terminus and port for the Uganda railway, then under construction. It was to replace Port Victoria, then an important centre on the caravan trade route, near the delta of Nzoia River. Kisumu was ideally located on the shores of Lake Victoria at the cusp of the Winam Gulf, at the end of the caravan trail from Pemba, Mombasa, Malindi and had the potential for connection to the whole of the Lake region by steamers. In July 1899, the first skeleton plan for Kisumu was prepared. This included landing places and wharves along the northern lake shore, near the present-day Airport Road. Demarcations for Government buildings and retail shops were also included in the plan.

Going, going, gone: The gradual death of Kisumu Railway Estate

The estates were built by the colonial government during the construction of the railway line to Nakuru. According to inscriptions on some of the walls, most of the houses date back to 1901, with the newest being built in 1910.

Sandwiched between two of the town’s biggest shopping malls, the estate has weathered the storms for over 50 years.

Photos below courtesy of Rajni Shah and others

ROYAL AIR FORCE KISUMU WITH ITS SERIES OF CRASHES

ROYAL AIR FORCE KISUMU WITH ITS SERIES OF CRASHES .....By Odhiambo Levin Opiyo Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

______________________________________

Royal Air force Kisumu was formed in Nov 1942 and was operationally and administratively controlled by Air Headquaters East Africa which was a command of the British Royal Airforce.

The first officer to assume the command of the new station was S/Ldr(squadron Leader) W.A Daust who was posted at the station on the 8th Dec 1942.

The station played a critical role during world war ll ,acting as a staging camp where British soldiers and equipments were prepared before military activities ,as a flying boat Repair station where flying boats of No 206 Royal Airforce carrying out maritime patrol in the Indian ocean were repaired and also as a military personnel transit centre.

However weeks after its formation the station was faced with a series of crashes partly because of the Royal Air Force pilots infamiliarity with flying in the area and also the strong winds from the Lake,

Although the locals also believed the crashes were being caused by the gods of the Lake who were not happy with the new facility.

The first crash was on the 23rd Nov 1942 just two weeks after the station had been formed ,when a Blenheim Z7679 from the fleet of No 70 C.T.C crashed 5 miles from Kisumu Killing a crew of four,.

They were: Sergeant Sinclair R.A pilot,Pilot officer D.E Button Observer,Sergeant Everet.H.J ,Fligh Sergeant Thomas L.Senior Observer..All the crew were buried in Kisumu Cemetry with service honours.

Three weeks later on the 19th of Dec 1942 a Lockheed .K248 took off from the station at 05.05 hours and crashed in Lake Victoria approximately 05.10hrs , killing a total of 12 which included the crew and senior Military officers among them Major General D. Pienaar a South African World war ll commander.

Despite the crash site being Just metres from the station it took Royal Air Force six hours to locate it .

The first Aircraft to carry out the search was a Baltimore AB 18c which took off at 06.45 hours but returned three hours later without a trace of the wreckage ,A Leopard Moth took off at 10.00hrs to conduct another search this it managed to locate the wreckage on bearing 215 degrees south from the hanger.

It is interesting how the British were so concerned with Salvaging the secret documents which were in possession of the dead officers from the Lake than the recovery of bodies.

While the documents were salvaged on the same day it took another two days to recover the bodies.The first 10 bodies were recovered on the 21st of Dec 1942 and the last two bodies on the 22nd Dec 1942.

All the bodies were flown in two lockheed aircrafts to South Africa from Kisumu on the 23rd of Dec 1942 ,with the third Aircraft carrying the salvaged documents also departing on the same day in the evening .A memorial service for the victims of the Lockheed was held in Kisumu church at 17:00 after the bodies had departed.

The last recorded crash was on 4th January 1943 when a Baltimore crashes South West of Kisumu ,although this wasn’t as fatal as the other two ,all the screw escaped uninjured except for Sgt Hoyle .M who broke his leg.

Royal Air Force Kisumu was closed after world war ll and the facility opened to civilian use.

Oginga Odinga Road, Nyanza Cinema was along that street, belonged to an Ismaili family called the Bhanji's, Gullu and Hassanali Bhanji two brothers who were so friendly and so warm. Kenview Cinema also belonged to the Bhanji family and was also situated in this white building in earlier periods (Bookshop/Chapel), this row of shops is opposite the Main Post Office.

Odhiambo Levin Opiyo...

Kisumu Market (Jubilee Market) It was established around the time King George V celebrated his silver Jubilee. How Kisumu

Municipal Market has evolved over the years.

Most Luos still call it with its original name "chiro mbero".

"Chiro" is Market and "Mbero" a small stool.

Kisumu- Kisuma - Okhusuma (luhya for to trade) Its close to Luhya, also luo for 'why don't you trade me this and that'.

By Odhiambo Levin Opiyo

Victoria Nyanza Sugar Company later, Miwani sugar company, was the largest sugar mill in East Africa in terms of production and also the oldest in Kenya.

It was established by the Hindochas in 1922.

In 1942 the company had over 9000 acres of land under cane on its two estates at Miwani and Chemelil.

The trucks carrying the cut cane to the factory were drawn by oxen over temporary railway lines in the fields, before they were loaded onto diesel trains operating on permanent railway lines.

Its milling plant had four sets of 4 by 6 mills preceded by a pre-crusher and had a capacity of 35 tons per hour.

The sugarcane juice was passed through different processes of purification and crystallization before it reached the drying machine and then to the bagging station.

The finished product which was ready for export contained 99.5% pure sugar .

By 1960 the total number of Africans working at the factory stood at 4000 ,many of them were Luos from the surrounding Central Nyanza reserve ,and about 1500 other Africans from further afield who were employed on contracts .

To cater for educational needs of children of its Asian staff, it set up Miwani Estate Asian primary school which had around 200 Asian children.

After independence the company was acquired by the government as part of the Africanization programme. It collapsed and closed down its operations in late 1990s.

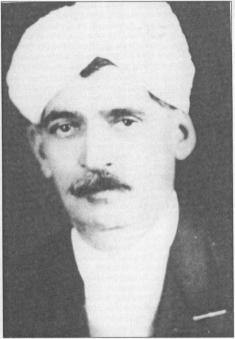

Fakir Chand Mayor 1878 - 1941

I am sure there are a lot of us who would love to visit a hereditary place or places where by one grew up or child hood place/places that somewhat grew simultaneously as part of one within one’s soul. It can be very enthralling experience if one ever gets an opportunity to experience it, I am afraid there is no guarantee but sometimes it is not always exciting when visiting, as it can send one into a different dimension that can have prolonged etched memories of a different kind that rekindles all sorts/types of emotions..

This is such a story that I would like to share with you all; it is well versed and

written and certainly is different to many stories that I have read.

Fakir Chand Mayor 1878 - 1941

Decades after his death, people still remember him fondly. In 1998, Manmohan Singh Shukla, a lawyer from Dar es Salaam, had a chance meeting with Dyal Singh a retired Sikh, in a village in

Punjab. The old timer began to reminisce about his days in East Africa and fondly remembered Fakir Chand as ‘ a kind and helpful man and a torch bearer for the Indian community’ narrated by Shukla,

Manmohan Singh. through personal communication.

A day after his death, an unknown engine driver stopped his train at night at the bridge near Fakir Chand’s farm. When all was quiet, a long melancholic whistle reverberated through the still air

from the Mau Hills to the lake, and from the Nandi escarpment to the Kano plains - a sounding of Last Post from one railway man to honour another.

MIWANI REVISITED

When an opportunity to visit this playground of my childhood presented itself in 1978, I jumped at the chance. The motor car had now become the king of passenger transport in Kenya so we approached the area along the new road at the foot of the Nandi Hills at the opposite end to the familiar railway station. A warm glow began to engulf my body at the very thought of meeting some old friends and the prospect of showing the community to my wife, Kusum.

We stopped the car at the very first farm that once belonged to my father, Durga Dass Dhupa. He had bought this farm as an investment and to keep my mother happy for she had a vision of

retiring there, just as her father had done. I doubt that my father had any intention, however, of ever soiling his hands. The farm was of course there, but little else. We pushed forward through a

thicket and came upon a heap of mud which looked like an anthill but for a few blocks of unbaked clay with specks of whitewash struggling to hold their shape against the ravages of time. These were

the only clues that these were the remains of a once fashionable farm bungalow. The rest of the buildings had vanished without trace.

The only deep well in the village which gave the farm its name, Khu walla Shamba, had long been filled in and ploughed over. Gone were the majestic mango trees and the jaman that stood

next to the bungalow. Gone too, was our ‘bird tree’, a giant Gum Arabic tree with hundreds of elaborate, and intricately woven nests of weaver birds dangling precariously from delicate branches.

Where once one could hear the chirruping of the hungry fledglings a hundred yards away, there was now nothing but stony silence.

As I cast my eyes over the rest of the farms, the feeling of nausea was only heightened at the realisation that all the farmyards had fallen prey to some devastating act of vandalism. It was as if a

tornado had swept through the entire area selectively sucking up all signs of human habitation into its sinister funnel. Only one shanty of wood and corrugated iron was still visible down the road so

we drove up to it and knocked on the cracked, ill-fitting door. We knocked again and again and eventually our persistence produced a belated response. The door creaked open and slowly a small, bent

and dishevelled figure emerged, squinting at the midday sun like some creature of the night unhappy at the sudden exposure to daylight. The man was emaciated with bloodshot eyes and his thinning

blotchy reddish hair badly in need of a cut and fresh henna. It took me some time to recognise that this was my old pal Inayat who had once shared my desk at school and taken part in our childhood

escapades. He could climb a tree faster than a monkey and bring down the choicest of ripe guavas. The isolation and pombe (liquor) had taken their toll and reduced him to a sad, bumbling idiot unable

to recognise his buddies. I tried to jog his memory but it was an exercise in futility. The time was short so we wished him well and pressed on.

We left, anxious to see our grandpa’s farm. The once elevated road, the backbone of our village, was now no more than two parallel grass covered ruts and eventually even these gave way to prairie. We

soon realised we had gone past the farm and reached the spot where the school once stood. We pushed through tall grass and clumps of cane and there, in front of us, was our alma mater, or at least

what was left of it. All we could see was the rusting but largely intact roof, for the rest of the structure was buried under a sea of sand due to repeated Hoods. An ignoble end to a fine

institution. The topography had changed so much that the small brook that ran in front of all the farms was nowhere to be seen and the railway main line that lay on a high embankment seem to be in

danger of being buried too.

We did not linger and back tracked a couple of hundred yards. The ancestral farm had suffered an even worse fate. The cannibalisation was so complete that not an iota of the farmhouse and the

surrounding buildings was left, all having fallen under the plough. All we could do was to stand and stare in disbelief.

Suddenly, my eyes came to rest on a tall, rather forlorn palm standing head and shoulders above the surrounding sugar cane, and it brought back a flood of memories and a vision of the whole farmyard.

Surely, this was none other than our old friend the ‘khajoor’. Years ago, a tiny strange looking sapling had mysteriously taken root under the plinth of the south bedroom. It had only avoided the

chop of a panga because grandma thought it was a date palm and everyone began to hope that one day it would be replete with succulent dates. Its uniqueness was perhaps its redemption for it had

somehow survived all adversaries that had laid everything else to waste. It had grown tall and proud and witnessed all the changes. It had the answers to all of our questions - alas, if only it could

speak.

1 could not resist the urge to go up to it and run my hand over its rough, dry trunk - a symbolic handshake, I suppose. As we were about to leave I noticed a half-withered stump and soon worked out

that this was the remains of our mulberry tree. This was the only tree of its kind in the whole area and it had been lovingly brought over by grandma from Punjab and nurtured with mulch and tumblers

of water until it was strong and tall. It had not only rewarded her by producing long, sweet purplish she toots but also doubled as a post to which the cows were tied at milking time. Here we kids

would stroke their wet muzzles and feed them supplements of salt, jaggery and leftover dough while the toto tied their hind legs and milked them. Occasionally, we would crouch beside him and he would

direct the milk straight from the teat to the mouth. Delicious!

Our visit was now over. We drove away with a heavy heart and a moist eye. On reaching high ground 1 felt compelled to slop and take one last look. My spirits were rekindled as I surveyed the

valley awash with the green and gold of hundreds of acres of sugar cane that had once grown in Punjab, swaying in the warm, gentle breeze. The houses and sheds were gone, but this, a living memorial

to the brown men and women from a faraway land who had changed this virgin weald to a land of milk and honey, would go on forever.

Now those men and women had gone too. Some had departed to meet their maker; others had gone to the land from whence they came. All, however, had left one thing behind - their

SPIRIT.

Chale aye nn reh guzaron se JALIB (1 have come away from those directions, Oh Jalib But I have left behind my spirit and my heart)Magar Hum wahan kalb o jan chor aye...

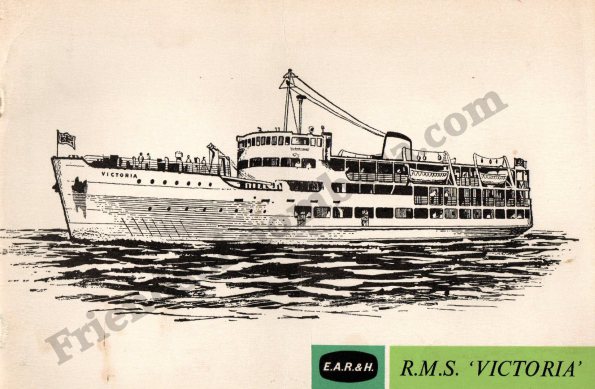

Lake Victoria Marine Services

Lake Victoria

Click below....