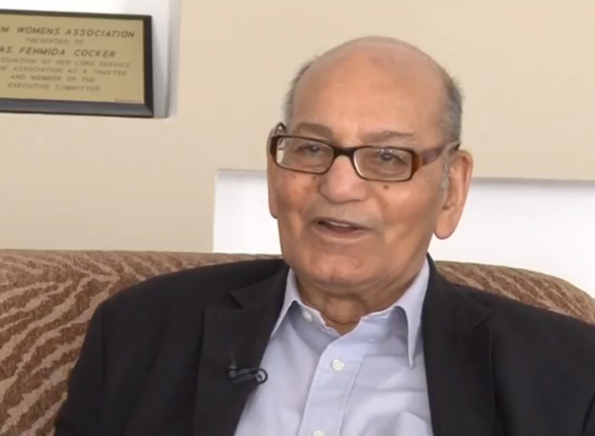

RTD. CJ MAJID COCKER’S MEMOIRS

By Winnie Kamau

As Kenya is about to celebrate its 52nd birthday since its formation in 1963 one man who rose from a teacher to being a Chief Justice in Kenya has served in and out of the Judiciary for 50 years. An accomplished sportsman retired Justice Majid Cocker is one who has not only seen Uhuru but also has experienced the pains and the joys of Uhuru. Coker who has been both an outsider and insider of the Judiciary has captured all the moments in his Memoirs Doings Non-doings and Misdoings of Kenyan Chief Justices since 1963 through to his retirement in 1998. We had a chance to visit and get an in depth of his life.

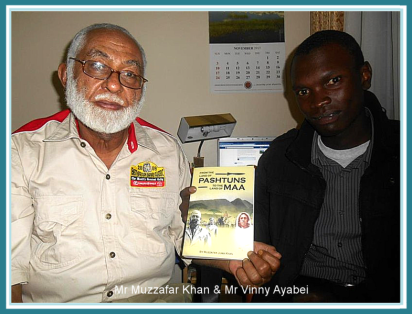

From the Land of the Pashtuns to the land of Maa by Mr Muzzafar Khan

By Mr Muzzafar Khan with his most committed helper Mr Vinny Ayabei.

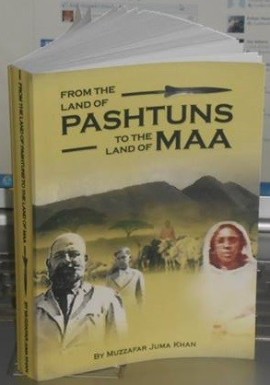

From the Land of the Pashtuns to the land of Maa

BOOK REVIEW by Prof. Fayaz Khan, Capital University of Economics and Business

In the book “From the Land of the Pashtuns to the land of Maa” we find an engaging and consummate narrator in Muzzafar Khan, a natural storyteller not encumbered with the conventional modes of storytelling. This book is his story and he has set about to tell it in a manner that can best be described as being in the style of a rousing fireside chat.

The book encompasses over eighty five years of the author’s family history in Kenya, and is told in a mostly linear, albeit sometimes frenetic manner; constantly weaving in and out of different eras and locales, at times rushing through a listing of names, places, events, and eccentric figures at a breakneck pace, while at other times slowing down and pausing to reflect and pay attention to interestingly quaint and attentive observations such as the precise registration plate numbers of the cars that passed hands within the family, or when the author takes liberty to go off on a tangent to fully flesh out a character and ends up giving the reader an insight into the antiquated hunting laws in place in those times.

In the opening chapters of the book a brief history of the early colonial settlement community in Kenya is laid out together with interesting yet relevant segues into the histories of India and Pakistan at the turn of the 20th century. This sets the scene for the arrival of Juma Khan, the patriarch of the family, whose singular ambition to find a better life for himself and his family establishes the early theme of the book.

What the writer understands and is able to clearly convey is that the story of his father, Juma Khan, is not just the story of one man, but rather it’s the archetypical story of the early Asian immigrant experience in Kenya.

Not content with recounting his memoirs in a by-the-numbers fashion, the author seems to have roped in a cast of thousands in telling his story, a remarkable testament in itself to the author’s sense of recall and memory.

Personalities abound on each page, some seemingly only transitory to the story’s progression and are mentioned in passing only for the author to double back on in later chapters and provide a second act for them, revealing an ever deepening extent of the interactions and influences they would have upon his life. It would seemthat, in a way, everyone in the early Kenyan Asian community was inevitably connected to everyone else.

Each of the people we encounter has a story behind them. The author has not neglected to tell us where they originally came from, how and why they got here, and in what manner was their contribution to the early history of Kenya. While it is generally assumed that most of the early Asian immigrants were laborers with peasant backgrounds who came to build the railway; the author, whose research displayed in the book is impressively exhaustive, often presents us with several peculiar origin stories that makes the early Punjabi community of migrants appear even more colorful than what has previously been assumed.

For instance when chronicling the person of Noor Dad Khan we learn that (allegedly) “… Ajibullah Khan had murdered a member of Noor Dad’s clan in India…a council of elders had then selected Noor Dad Khan to look for him in Africa and carry out the [revenge] sentence.”

Muzzafar Khan, being a man of abundant personality and an inquisitive mind takes on interesting detours and diversions in telling his story. This is evidenced by the inimitable blending in of the major themes of the bookwith his own personal passions. Recollections of living amongst the Maa people, growing up in a large polygamous and mixed heritage household is effortlessly interwoven with the writers interest in religious discourse, his fascination with aviation, his love for motorsports, or his need to properly address the issue of an Afro Kenyan social Identity. It is not strange at all to find a passage in which one moment the reader is being informed of the remarkable similarities between the Maasai and Punjabi term for elderly brother (Apaiya / Paiyya), and a few moments later to encounter an interesting tidbit about the Qaddriya Sufi sect in Islam.

The accounts and exploits of the early Asian communities in the stories relayed in the book prove to be anything but dull. There are stories of hardships encountered, family feuds, tragedies borne with tough stoicism, business ventures into unknown territories, social relations with both the local and white settler communities, and even the occasional arguments that escalate into gun wielding and knife baring challenges. The stories are brought even more to life by the inclusion of several aged, and black and white photographs of some of the characters that are included in the book. There are pictures here of swarthy mustachioed men with stern features, traditionally attired chador cladded women, family portraits with children in the double digits, and in one or two interesting cases a loin clothed Asian individual completely at ease in his rustic rural Kenyan homestead.

The later parts of the book acquires a more somber tone as the writer delves into the intriguing saga of the history, evolution and eventually the demise of the Kenya Farmers Association (KFA). This was an organization at which the author spent twenty six years of his life as an employee. Muzaffar Khan’s rise from a simple clerk to Managing Director is a remarkable tale in and of itself, however he is not content with consigning the downfall of the KFA to a mere footnote. With an insider’s knowledge of the events that led to the organizations downfall, his rendering of the events makes for captivating reading that is at once both illuminating and incendiary.

The sense of loss and disappointment at the ruin of this once illustrious institution is palpable and clearly conveyed by the writer. It is not just dismay at the financial collapse of the institution that irks the writer but the callous unconcern for the institution’s place in Kenya’s history, as is highlighted in an incidence involving the portrait of an early-era chairman. This theme of decay and disregard for the past is not confined to just the KFA. The writer mentions how he undertook to revisit many of the places where he grew up, when writing this book. The picture painted is often not cheery as many of these places have deteriorated and fallen into ruins.

One wonders, could this be the reason why the earlier part of his book is so replete with the countless names and biographies of other early generation Punjabi settlers? Not much has been recorded about these brave young men and women by the way of their personal stories in the past and he knows only too well from experience the ease with which their histories too could sink into impotent obscurity just as the KFA did.

This is not so much a book about the re-telling of history or an expose into the failings of a government institution. It is about the preservation of memory and an attempt to pin down all those memories into a tangible understanding of the author’s own history and identity. In the end what has emerged is the story of a life fully lived and it has been told in a candid, personal and dignified manner in this sprawling and moving memoir.

Interview with Muzzafar Khan of Daman village (Hazro),

PLEASE SHARE THIS LINK WITH YOUR FRIENDS AND FAMILY, THANK YOU

Basheer Mauladad: A life of service

Please click below

https://nation.africa/kenya/news/basheer-mauladad-a-life-of-service-990288

Basheer Mauladad (1931- February 13, 2014) was a prominent Kenyan social worker, sportsman, leader, philanthropist and successful businessman.

He was born in Nairobi in a family well known Kenyan

Asian family.

His father, Salim Mauladad, was a successful civil engineer in East Africa and Basheer took over the family business while his older and more colourful

brother, Iqbal, became the famous hunter, "Bali".

Basheer was punctual to a fault, and though wealthy, led a very regulated and modest life.

Simple, modest, gracious and courteous to all.

Basheer Mauladad won the hearts of all he served and became a model of excellence.

He was influential in breaking down the colour bar in Kenya and negotiating independence.

The Muslim Association conferred on him the Award of Excellence in 2012 for his services to the Muslim community and Kenyans at large.

Basheer was an encyclopaedia on the history of pioneers of the Punjabi Muslim Community and ultimately led to the publication of “Settling in a Strange Land” written by Cynthia Salvadori

which records the history of the families that came to Kenya between 1850 and 1940.

He was survived by his wife Nusrat Mauladad, daughter Shaila Mauladad Fisher.

(Credits: Coast Week & WIKIPEDIA)

Click on Photo

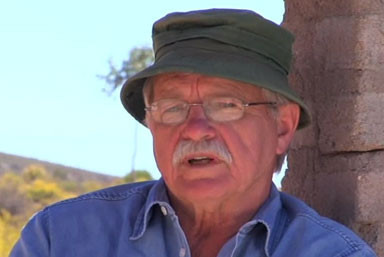

In Memoriam: Piet Hendrikse, 1944 – 2013

Tragically, Piet Hendrikse, the inventor of the Q Drum passed away on 30 March 2013.

Piet's legacy will live on through the Q Drum and the Directors of the Company will ensure its continued manufacture and supply.

Our thoughts are with his family, friends and colleagues during this difficult time.

Ameer Janmohamed

Click on Photo

Condolences: announcing the death of Mr Ameer Janmohamed. (formerly of Badrudin Sports House), and author of the Regal Romance, in London.Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un (إِنَّا لِلّهِ وَإِنَّـا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعونَ)

Mr Ameer Janmohamed.

My heart goes out to you and your family during this difficult loss. Respect to the people that are no longer with us but they continue to live amongst. We all have a journey and leaving memories is an honour to his loved ones..

Death leaves a heartache no one can heal, love leaves a memory no one can steal. The greatest compliment to someone who has passed on is to breath and live your life and keep their memory alive.

I went to school with Mr Janmohamed junior and was a good friend and a classmate, sadly we never met after 1967.

God Bless

26/01/2014