Trench diggers at Mama Ngina unearth 13th Century mosque

The discovery, the Star exclusively learnt, has unearthed rich historical materials, signifying a major breakthrough to scientists and researchers. The artefacts include pottery, bones, metals, beads and stone tools.

Two large areas at Mama Nginahave been cordoned off.

President Uhuru Kenyatta last month commissioned the project and directed that the land be reclaimed and all grabbed parcels be repossessed.

The NMK says part of the discovery will be aligned to the timelines set by the President of having the park operational in five months.

On Monday, the Star witnessed the excavation of items that could turn around to the beautification project.

The mosque, a few metres from the Likoni ferry crossing, will make Mama Ngina not only a cultural, military and aesthetic front, but a spiritual one as well.

Coastal region NMK keeper of heritage Athman Hussein said the place will become a unique recreation centre in Africa as it will combine leisure, culture and interaction of the original ruins of the 13th Century.

The NMK will team up with Prof George Abungu, from Abungu Heritage Consultancy, who was called to assess the area and the discovery. Abungu is an archeologist.

In the near future it is expected that Mama Ngina will be among the most popular sites in Kenya. It is projected to attract more than two million visitors annually.

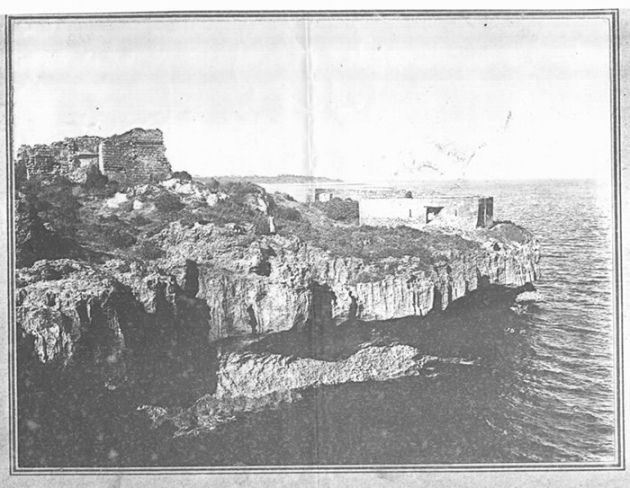

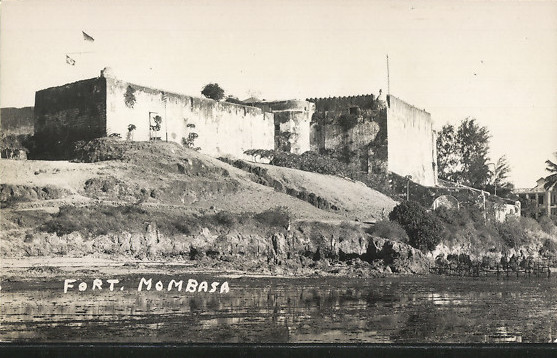

Old Fort St Joseph

Who built the original Fort St. Joseph ? The Arabs, it is thought so, It is probably the oldest fortress on the island. Remnants of the wall still stand near the Lighthouse. Older than Fort Jesus, it stood when Vasco Da Gama first came to Mombasa 1498.

Located on the Golf Course near Mama Ngina Drive (04 04' 18,1" S 39 40' 56.1" E); Fort St Joseph is a horseshoe-like fortification in good condition. At about 100 metres distance to St. Joseph it was the Portuguese chapel "Nossa Senhora das Merces" (Pos: 04 04' 21,2" S 39 40' 50,7" E). In 1999, the National Museums of Kenya succeeded in halting unauthorized work at the 17th-century Portuguese fort, one of the first sites gazetted in 1929. Developers had acquired the land through a questionable title reallocation and started work on a hotel, posting spear-wielding Maasai guards who refused entry even to the judge hearing the Museums’ case.

Cont: http://indicatorloops.com/mombasa_forts.htm

FORT ST. JOSEPH

Who built the original Fort St. Joseph? The Arabs, the Arabs I should think. It is probably the oldest fortress on the Island. Remnants of the walls still stand near the Lighthouse. Older than Fort Jesus, it stood when Vas-da- Gama first came to Mombasa in 1498. He recorded that ‘Mombasa is a large city seated on an eminence' facing the sea .... at its entrance stands a pillar by the sea a low lying fortress.’ This old place was probably razed when Mombasa was sacked by the Portuguese in 1500. 1550 Ali Bey, a Turkish corsair, arrived at the island and was hailed by the local Arabs as their deliverer. He drove the Portuguese from the coast line, plundered them of £600,000 worth of their possessions and sailed for home.

When he returned he found that the remarkable tribe known then as the Zimba had overrun East Africa from the Zambezi to Mombasa. Ali Bey built another fort at Ras Serani and prepared to defend himself and his Turks. Later that year the Portuguese arrived in force, and Ali Bey combined with the Zimba in order to beat off the new enemy. He was defeated, however, taken prisoner. The Portuguese enlarged Ali Bey’s fort, gave it the name of Fort St. Joseph and built a chapel within the walls of the chapel of Nossa Signora das Merces. A few yards from the main ruin is the entrance to the underground passage which, legend has it runs to the central courtyard of Fort Jesus. The outlet, however, if it ever existed, has never been found. At the beginning of the war engineers made a further attempt to find it, but without success. Well, there’s little enough left of this famous old Fort St. Joseph. I sincerely hope that this little will be preserved. Edward Rodwell

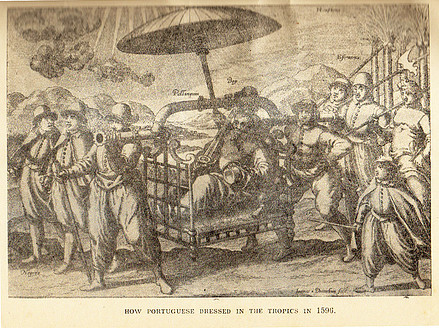

How the Portuguese dressed in the tropics of 1596

I bet people must be wondering how the Portuguese dressed during the occupation of the Island around year 1600? The ancient engravings above showing how the soldiers and merchants dressed, and they clothed their native and Arab servants.

They were not as half as romantic-looking as the mind’s eye visualises. The soldiers , bold-looking bearded men wore hats that look like beefeaters’ hats, a small frill at the neck, a leather jerkin, with long sleeves, and voluminous pantaloons that reached down to the ankles.

Their feet were shod in golosh-like shoes. Further, to protect them from the sun, they wore either a long or a short cloak. The sword belt was very narrow and fitted over the jerkin. The sword seemed very long, for foot soldier to use they’d have to be in this country. Visiting St Joseph or over at Makupa, they’d have their brolly –bearers along. These tall fine looking natives or Arabs walked behind the large umbrellas keeping the sun from their masters’ topsides.

There was not much difference in the dress of the merchants. Their frills were a little more gaudy, and they wore flat pancake hats. Merchants’ swords were short. The brolly-bearers were dressed in jerkins and pantaloons reaching the knees.

They were barefoot as warranted their station. Some wore turbans and one look as though he is wearing a Custom fez which has lost its stiffening. Coming, home Makupa or Fort St. Joseph all would no doubt look a little different.

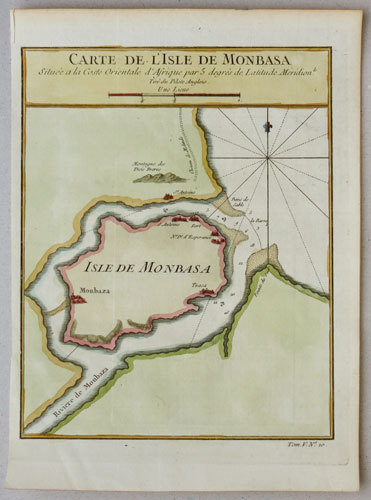

One of the few early maps of Mombasa

Jacques Nicolas Bellin.

Amsterdam, 1747. The island of Mombasa with its city, from Prévost's 'Histoire des Voyages'. An important port, Mombasa was fought over by the Portuguese and the Arabs (particularly the

Omanis) for centuries. However at the time of publication Mombasa had just declared itself independent of both, under the first recorded sultan, 'Ali ibn Uthman al-Mazru'i. The title 'Monbasa' is

closer to the Arabic name 'Manbasa'.

BELL0183

A relief force from Mozambique of some 150 Portuguese and 300 Indians fought its way into the besieged Fort, but despite this help the Fort was entered by the Arabs on 12th December, 1698, and the Red Flag of Muscat was hoisted, for the first time, over Fort Jesus.

PORTUGUESE influence over Mombasa, which dated from Vasco da Gama’s voyage to East Africa in 1498, may be said to have begun to decline from 12th December, 1698, when after a siege lasting 33 months the Arabs from Oman captured Fort Jesus. They had forced an entry into Kilindini Harbour in 1696 and, having captured Fort St. Joseph, they isolated the garrison of some 50 Portuguese and 2,500 natives in Fort Jesus. The end of the Portuguese resistance was hastened by an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Fort.

In August, 1697, the Commandant, Antonio Molo de Mello, died of plague, and the Prince of Faza assumed command. A relief force from Mozambique of some 150 Portuguese and 300 Indians fought its way into the besieged Fort, but despite this help the Fort was entered by the Arabs on 12th December, 1698, and the Red Flag of Muscat was hoisted, for the first time, over Fort Jesus.

Nazir bin Abdulla, a member of the Mazrui Clan, was appointed Liwali of Mombasa. The Porluguese made several desperate efforts to regain Mombasa—in 1699, 1703 and again in 1710—but it was not until 1728, when the Mazrui and Omani fell out, that the Portuguese had any measure of success and regained Fort St. Joseph and then recaptured Fort Jesus. Their success, however, was short-lived as the Mazrui and Omani combined again and finally drove out the Portuguese in 1730.

The Mazrui Clan again dominated Mombasa and when the Sultan of Oman withdrew his men and ships from Mombasa to help fight the Persians who were attacking Muscat, the Mombasa Mazrui Liwali Mohamed bin Athman renounced his allegiance to Oman. Thus began in 1730 the Mazrui interregnum which was to continue until 1828.

In 1739 the Yo-Rabi dynasty ended in Oman and throne was occupied by the Al- Busaid dynasty which, to this day, reigns in Zanzibar. In 1804 the most remarkable personality of this dynasty, Seyyid Said bin Sultan succeeded while still a minor to the throne. During his minority his maternal uncle acted as Regent, but the real power rested with the young

Sultan’s aunt, Bibi Mauza who intrigued against the Regent, and caused him to be stabbed to death by the young Said. During the first decade of Said’s reign he was fully occupied in subjugating the Wahabi who molested Muscat. In 1822, however, he turned his attentions again to East Africa. He was invited by the Sultan of Pate to deliver them from the Mazrui, which he did. He then seized Pemba and, as this constituted an immediate threat to Mombasa, the Mazrui sent messengers to the Government of Bombay to solicit British help against the Oman.

In 1823 Said was besieging Mombasa. It so happened that during the early months of this year, two British ships—H.M.S. Leven (Capt. Owen) and H.M. Brig. Barracuta (Capt. Vidal) were carrying out a hydrographic survey of the East African coast, and were in the vicinity of Mombasa. The Mazrui Sheikh Sule- man, after many pleadings, induced Captain Owen to declare Mombasa a British Protectorate, and hoist the British Flag over Fort Jesus.

Owen concluded a treaty which recognized the Mazrui as the hereditary rulers of Mombasa, Pemba and other parts of the East Coast. The Customs revenue was to be divided with the British, and a British Political Agent was to reside in the town. Trade with the interior was to be permitted to British subjects, and the slave trade was to be abolished.

In declaring a Protectorate over Mombasa, however, Capt. Owen had taken upon himself an immense responsibility. He counted on powerful allies in London, he was well connected—his brother, Sir Edward Owen, being the Commander-in-Chief of the West Indies—- to support him. In his despatch to the Lords of the Admiralty he made as much as he could of the “Strategic and Naval possibilities of Mombasa”, and warned their Lordships that France might seize the coast if Britain neglected this opportunity.

Owen, in his book, “Narrative of a Voyage of Discovery to Africa and Arabia”, performed in His Majesty’s ships Leven and Barracula from 1821 to 1826 under the command of Capt. W. F. W. Owen, R.N., says: “I sketch lo myself a perfect harbour in Mombasa. It affords good riding ground at the entrance. With respect to its situation as a mercantile port—English manufactures brought out in large ships could be retailed from Mombasa lo the whole coast line.

Occupied by the English it would serve as an excellent half-way house, as a retreat from an enemy and—in case of danger—as a port of refit. As a military port it would, by its resources, tend greatly to check the slave trade”. (Owen’s prophetic words came true when, after the fall of Singapore, in 1942, the British Eastern Fleet fell back on Kilindini which then became a naval base and repair depot and a convoy port of assembly.)

Owen was eager to ratify his treaty with the Mazrui and sailed for Mauritius with Mombarruk, the nephew of the Sheikh of Mombasa, to interview and win over the support of Sir Lowry Cole, Governor of Mauritius. In his absence he left behind Lieut. Reitz, R.N., as Governor of the Fort, who unfortunately died of malaria some three months later, his name being perpetuated in Port Reitz. The Governor of Mauritius was won over to the idea of a British Protectorate over Mombasa subject, of course, to the approval of His Majesty’s Government in London.

Owen returned to Mombasa and started lo frame laws of government and then tried to induce Mogadishu, Brava and Lamu to join in with Mombasa. The Government of Bombay had, however, in 1822 entered into a firm agreement with Imam Seyyid Said of Oman which became known as the “Moresby Treaty”. This treaty recognized the “Imam’s overlordship” over the East African coast in exchange for which the Imam agreed to prohibit the sale of slaves to Christians, and to authorize the British Navy to seize any ship carrying slaves. Owen was fully aware of the existence of the Moresby Treaty when he sailed for Mauritius, but he depended on his influence at home to support him.

The British Government, however, upheld the terms of the Moresby Treaty and gave full recognition to the claims of the Imam over the East African coast, stating:—“It was His Majesty’s pleasure that no further measure should be taken upon the subject”. Thus in 1824 ended the “One Year Protectorate over Mombasa, and the British flag was hauled down from Fort Jesus, but not before the Mazrui Sheikh had addressed a petition in vain to His Majesty King George IV.

Seyyid Said, however, did not capture Mombasa until 1828, and then only after severe fighting. Said had then to return to Muscat to quell a rebellion there and left a garrison of 300 Baluchis in Fort Jesus. The Mazrui again seized power and, it was not until the Imam returned with a large fleet in 1837 that the indomitable town and the Mazrui finally lost their independence. Mombasa was then incorporated into the dominions of the Imam Seyyid Said, who, in 1832 had transferred his Court from Muscat to Zanzibar. Mombasa remained his sovereignty until the Treaty of Brussels in 1890, when a British Protectorate came into being by the “Foreign Jurisdiction Act” of August, 1890.

Capt. Owen and his officers, Lieuts. W. Mudge and Boteler assisted by Lieut. Nash and Midshipmen Barette and Tudor, charted Mombasa Island, its adjacent sea and creeks and published their chart in 1824. This chart is amazingly accurate. The latitude of Fort Jesus was given as 4° 04' S. and its longitude 39° 38'. While the latitude is correct to the nearest minute, the longitude is, however, 2.5 minutes out. Considering that in 1824 there were no means of checking the error of the chono- meter, other than by “Lunar Transets” this longitude is very accurate indeed.