Malindi/Lamu

Malindi, Kenya

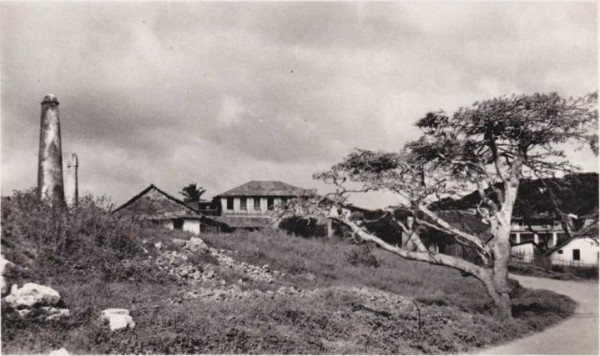

Neither Arabs or Africans consider those pillar tombs to be phallic but it's kind of hard not to. They are said to have originated in Somalia and were undoubtedly a nod to fertility rites of some sort. The Galla tribe from Somalia took over the mainland Swahili towns in the 17th century, but how these pillars came to be grafted on to Muslim tombs is still a mystery. This one is right next to Malindi's Friday Mosque.

Malindi

Location

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Galana River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa.

Views and Vistas

Malindi is served with a domestic airport and a highway between Mombasa and Lamu. The nearby Watamu resorts and the Gedi Ruins (also known as Gede) are south of Malindi. The mouth of the Sabaki River lies in northern Malindi. The Watamu and Malindi Marine National Parks form a continuous protected coastal area south of Malindi. The area shows classic examples of Swahili architecture.

Malindi is home to the Malindi Airport and Broglio Space Centre. The town began as a Swahili settlement in the 14th century. Many remnants of Malindi’s colourful past still can be seen. Malindi is a melting pot of ancient and modern culture, it is also a very popular tourist destination, with numerous resorts, restaurants, markets and a host of activities for holiday makers visiting the region.

Cont:

http://africanquest.co.ke/packages/malindi/

Images

This is extracted from a 1940 Magazine that somewhat brings back tons memories to many who may have lived there, may have been to Malindi for a holiday, school trips or sightseeing….

A Fascinating historical place that has been talked of, by so many people over the years, who have had an experience/s.

COMPARED to Europe the tempo of life in Kenyan Highlands is not exactly swift while that of the Coast is even slower. As regards the sleepy little village of Malindi this is not surprising since it lives mainly on and for the settler community, exhausted after carrying the White Man’s on farm and plantation.

Tin more lethargic atmosphere is noticed as soon as you leave Mombasa when the road immediately narrows and swift progress is arrested by having to cross two ferries, at Shimo-la Teva und

Kilifi. These ferries are first class affairs with good decking and they are efficiently worked with a “ ship ” at either end.

The method of movement in use is a long cable stretching Mill across the creeks and it is buoyed regularly: five natives nil I lie ferry across by heaving on the cable stretching right across the

creeks and it is buoyed regularly: five natives pull the ferry across by heaving on the cable: like all natives working on water they chant melodiously and progress is positively rapid. Ferries are

legion in Central Africa and many of them in the Belgian Congo, and still more in French Equatorial, are rickety affairs supported on leaking dug-out canoes; entry and exit is a hazardous and

exciting business.

If your idea of a holiday is a sort of super lotus eating one then Malindi is the place for you; for a week or two, as a change, there is a lot to be said for a rather pointless life.

The main amusement is bathing, bathing, and more bathing. Apart from this there is little to do save to drink, alcoholically or otherwise, in a house you may have rented, or at either of the two

hotels. The more energetic can of course get a lot of exercise, that passion of your true blue Englishman, by exploring the very spread out ruins of Gedi but eleven miles south on the Mombasa road:

a noticeable feature of these ruins is that the arches are pointed, not rounded as in those in Malindi.

Another amusing pastime is fish stalking or perhaps it should be called fish hunting or shooting. But for this you need a certain amount of gear. A fish “ gun ” six foot, small harpoon, a spear,

line, and under water goggles. And unless you are one of those tireless swimmers, a life- saving belt. The gun is worked either by an arrangement of elastic, or better by a strong spring.

Most East Africans are familiar with the launches at Port Sudan with their glass bottomed boxes hung over the side through which one sees gaudy coloured fish and beautiful shaped coral. Fish stalking

is the same thing with this great advantage, that you “ cruise ” where you fancy and for as long as you feel like it, instead of having the boat moved just when you have espied a particularly amusing

fish. The goggles, by means of elastic bands, fit tight over the eyes and on either side of the nose. It is advisable to wear a pair of canvas shoes for coral is painful stuff to tread on. Even if

you yourself do not actually hunt the fish, many a pleasant hour, can be spent watching someone else hunt, or in just observing the fish going about their lawful occasion.

Somehow a fish in its own element in infinitely more effective and more attractive than one out of the water, there is grace in every turn and flash of many hued sides, in the curl of a tail or bend

of a fin. The colours are unbelievable, reds, greens, blues, zebra, marked little fellows, rainbow coloured” middles,” and the hieous large headed rock.

Another amusing fish is the parrot fish so named on account of its resemblance to this spry and twinkling eyed gentleman. His face is remarkably parrot like while his body is striped gold and blue

with great depth to it.

The technique is moderately simple. You float or swim and paddle gently along peering into dark caverns, past little coral atolls, over sandy stretches and alongside cliff lets. Having spotted your

fish you submerge, work within range, and “ fire ” at your quarry. It is as well to remember that he is always sure to be further away than you imagine.

Under water even a five pound fish will put up a good struggle before you can force the spear into him and take him to the surface. An eight pound fish seems like a monster and of course the line becomes entangled in lumps of coral, and you have to free it, which is not as easy as it may sound. Fish up to twenty-five pounds have been “ boated.” A minor excitement is beaching an octopus, revolting to look at though those sinister looking tentacles make excellent eating. A curious fact about this fish hunting is that one keep one’s face under water, at least the important parts such as nose and mouth, far longer than one would believe likely, due no doubt to one being interested in watching the fascinating life below one. As soon as any fish is removed from the water part of its beauty disappears and it loses its glossy and delightful sheen at once as does an Impala once it is shot.

The weird shapes of coral, some like fairy temples, seemed to me a never ending pleasure with the octopus like tentacles of varied seaweed swaying, twisting, and turning in the current. The best place to indulge in this sport is just off a coral reef which is exposed at low tide near Vasco da Gama’s pillar. A two hundred pound rock cod which could swallow a man with ease cannot be too pleasant to meet but they, like most big game, merely desire to “live and let live.” It is pleasant cruising about in this fashion with huge breakers out to sea, which appear at times to tower above you, and you to be downhill of them, but as they are in reality breaking on a reef further out they are not really alarming. Some people can stay hunting for three hours on end; the water varies considerably in temperature according to whether you float over deep or shallow water, and through your area flows a considerable current. At this game man appears a clumsy and poor beast beside the elegant fish.

There is also the more orthodox type of fishing with hand lines or rod. Rock cod are excellent eating but parrot fish are indifferent; one needs to stay still in those crazy looking dug-out

canoes in spite of outriggers; the canoes are hewn from a single mangoe tree.

The natives use hand lines, nets, and traps, and the fishing is in the hands of the Swahili.

Another feature of Malindi are the Mongooses which can often be bought from natives. They are entertaining little creatures about six inches long although a trifle rat like appearance. They are neat little beasts with remarkably close set ears and when they lie sunning themselves they look not unlike a seal on a miniature scale. For the size of head the jaw* are enormous with a row of baby saw like teeth; the mouth in fact actually resembles that of a shark. The eyes and tips of. the nose have a red tinge to them. They are affectionate beasts who will purr after the manner of a cat; they have a habit of getting into the most unlikely places such as the cylinder block of an engine; they are full of pluck. Being so small they do not require much food and a little meat or fish keeps them fit and happy. And of course they adore eggs. Their method of drilling with them is swift and amusing; they squat over the egg, roll it just under them and then lifting both hind legs simultaneously, they hurl it with speed and violence against handy wall. Annoyance is registered if you tease them by giving them a hard- boiled egg. Sometimes they mistake turnip or potatoes for eggs and are pained when after much hard work objects remain inviolate. Their speed of movement is amazing. Another favourite sport, and also a change of diet, is obtained by hermit crabs, a species of land crab. It too is hurled against a wall until it either cracks, or gives up the struggle, when it is delicately devoured.

Other beasties are the millipedes of which there are millions; they are black in colour with brilliant red legs which move in batches like the tracks of tractors or a moving stair- case; they are quite harmless yet distressing to find in bed; many are squashed daily by cars and the ubiquitous cycle.

Living is good and cheap at Malindi where the main diet is fish and fruit; your more definitely carnivorous animal can satisfy his wants by getting meat from Mombasa on a daily lorry; vegetables also come out daily. The few stores are run by Arabs and are very poorly stocked. There is a daily mail, telephone, and telegraph service, and an airfield, so one is far from cut off.

The local natives are the Giriama who tire mainly agricultural although they have considerable herds of goats but a few cattle on account of “fly.” There are also a number of Arabs and some of the population in mixed to a degree. The Giriama smell strongly of castor oil with which they love to anoint themselves. As servants they seem little worse than many of the other tribes and better than some. The women wear kilted skirts made of yards and yards of Americani pleated into two inch pleats; some are dyed red, others black, while some are white till they turn a dirty grey from age; there is no significance attached to any colour.

The town itself is uninteresting and rather drab with few buildings worthy of the name. It fronts on to the bay of Malindi and is inevitably palm fringed; like all palms these look far more effective in reality, as well as in photographs, when silhouetted against the sky and backed by moon or sun. The houses are roofed with palm leaves and they all have hip roofs under the long side; this allows for a further current of air to circulate. The sides are of Mud or coral. If one dug anywhere near Malindi one would find ruins of a sort, but mainly alike. There is an old ruined mosque in the middle of Malindi and a wall near the front which shows the thickness of the walls built in olden days.

The bathing can be classed as good for those who like a sandy beach and have a passion for surfing. Good fun can be had with three ply surf boards once you have learned the knack of

heaving yourself on to the board at the right fraction of a second, but anyone who likes diving is badly undone. Some enterprising individual might fit up a raft some way out and erect on it a

plethora of diving boards.

Land crabs abound to intrigue or scare children and the lobster pot enthusiast can have fun with pots after the wily crayfish. On a moonlight night and lowish tide the sand is positively alive with

scuttling land crabs looking ghostly in the moonlight.

Just by the modern lighthouse is one of Vasco da Gama’s pillars, a white obelisk surmounted by a cross and to-day but stressed up with concrete pillars to prevent the tide undermining its foundations. In that vicinity are some quaint coral formations; there is a perfect bridge, and masses of knife edged cruel looking ridges. In one place the wash of ages has formed a series of potholes in a tableland of coral; at high tide the sea is forced through them causing of foaming a pleasing cascade of foaming water.

In brief, to the jaded and nerve wracked farmer Malindi offers peace and quiet, unless one goes with a large party determined to make whoopee, when of course you can lead a riotous life.

During the popular months of July and August the South West Monsoon blows a gale at night and part of the day, bringing with it sudden downpours. This “ popular ” season is doubtless governed by school holidays but in many ways January and February with the lighter North East Monsoon are really nicer. At all times dhows from Mombasa, Lamu or Arabia swoop in looking like giant swans. The force of the South West Monsoon is shown by a number of baobab trees on an exposed promontory where the branches grow mainly on the North side of the trees. The dawns and sunrises in the summer season ” are disappointing but this loss is made up for by some superb moonlight effects. A week or two of Malindi, apart from being a change, must do those who live at a high altitude a lot of good, even if they have to submit to a beach-combing sort of existence.

GEDI

The thirteenth century was one of turmoil. The crusades were in full swing, the Mongol empire under Ghengis Khan swept forever westwards while

Marco Polo turned his own eyes towards the east.

Meanwhile in Kenya, East Africa, a group of enterprising people began to build a settlement which would endure for over three hundred years. Gedi, a sophisticated coral-brick built town belies the

perception many have about this part of Africa - and its architecture - before the arrival of Europeans. Take a look at Kenya's hidden history revealed.

http://www.kuriositas.com/2011/12/gedi-kenyas-hidden-history-revealed.html

Gedi the Lost City

Gedi is one of Kenya's great unknown treasures, a wonderful lost city lying in the depths of the great Arabuko Sokoke forest. It is also a place of great mystery, an archaeological puzzle that continues to engender debate among historians.

To this day, despite extensive research and exploration, nobody is really sure what happened to the town of Gedi and its peoples. This once great civilization was a powerful and complex Swahili settlement with a population of over 2500, built during the 13th century. The ruins of Gedi include many houses, mansions, mosques and elaborate tombs and cemeteries.

Despite the size and complexity of this large (at least 45 acre) settlement, it is never mentioned in any historic writings or local recorded history.

Cont:

http://www.magicalkenya.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=224&Itemid=262

IS GEDI PERSIAN?

One day, someone is going to take a pickaxe and go to Gedi. He’ll probably dig down a couple of feet or so, and find a pot, or a coin. And with the find will go all our vague imaginings and romantic conjecture. It will be a pity, in a way, for the place is still spoken of in whispers and the tales of spooks and silent tombs send shivers along folks’ spines. We tell and listen to the stories with the same thrill as we listened to ghost stories when we were young.

We think that the bits and pieces to be found will be of Persian origin. For there are many signs of Persian influence in East Africa. The Swahili are supposed to be descendants of the race. There are old unusual names which are or may be Persian. On a little island near Mafia is the old place of Kua. It looks much like Gedi. And at Kua have been found Persian coins and bits of Iranian porcelain. There is another place on Pemba with the same characteristics.

On the island of Pate there are a few families who are said to have come from Persia. The Wagunia, who speak a Swahili dialect are said to be Persians from Kangoni, near Shiraz. And then there’s, the mitepe (the sailing boat made completely from wood). The mitepe carries three pennants on its prow. One of these pennants is in honour of a Persian sultan who lived long ago in Shanganya (where Kismayu now stands). With all these facts, and many more, it’s not a wild surmise to say that Gedi might have been built by Persians. It’s worth working on the assumption for a while, anyhow.

As for Wikipedia, it is widely accessible to ordinary individuals who are not renowned historians nor established prominent figure/s with any kind of affluence in the subject available at hand.

Lamu

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamu

Images:

https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=lamu&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=-N-ZU9vWDZGS7AbXjYCgBA&ved=0CDQQsAQ&biw=1252&bih=602

Shela

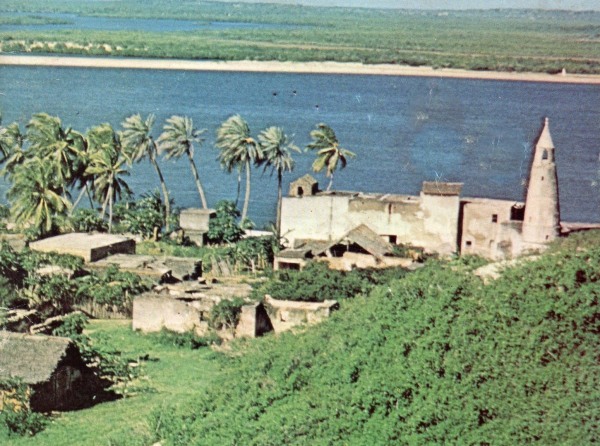

Shela (Near Lamu) 1973

Shela, two miles from Lamu town, is an attractive small village in spite of having lost its prosperity. The origins of the town are obscure, but according to traditional history, when the town of Kitau on nearby Manda was sacked by the Sultan Omar of Pate in the middle of the 14th century, many of the inhabitants fled to Lamu. They remained there for about 200 years, living socially apart from the Lamu people. Eventually, the Kitau refugees asked permission from the Sheikh of Lamu to build their own town. The Sheikh agreed, provided that no tall stone buildings nor a wall around the town be erected which might in the future lead to Shela becoming a rival to Lamu town and thus a security risk. In the latter part of the 16th century, the building of the town of Shela began.

Shela reached her apogee during the nineteenth century, especially from 1829 to 1857, during which period five of the town’s six mosques were constructed. Most of the inhabitants then were Arabs who held large plantations on Manda island, Mkunumbi, Pangani, and Kipini. Shela was much larger than today, and her stone buildings were spread almost to the present Lamu Ginners. When the slaves began to leave the Lamu area around 1890, the Arabs’ plantations rapidly declined since there was no one to work on them. Many of the Arabs themselves left the town of Shela to take up business or employment in Mombasa.

Today Shela has fewer than 250 people, most of whom are Bajun fishermen and farmers who cultivate small plots behind the village. There are few men between the ages of 20 and 50 because most have gone down to Mombasa to get jobs; many of them can be seen selling vegetables and fruits at the Mackinnon Road market in central Mombasa. Of the 100 stone buildings still standing in Shela in 1969, over 40 were unoccupied. Some of the inhabitants have used the walls of them to support new mud-and-wattle houses, but sometimes there is not even enough money to purchase a new makuti roof. But these impoverished people still have a feeling for the architecture that they can no longer reproduce: they support their simple houses against the most ornately plastered walls. Shela has a further difficulty in that sand dunes during the past 80 years have been encroaching and are gradually covering many of the fine old buildings.

Aesthetically, Shela is one of the most attractive villages in Kenya. The decorative plaster work found in the old houses is some of the finest seen on the coast; unfortunately, nobody does this kind of work anymore and so what remains has become invaluable. The Friday mosque is the highlight of any visit to Shela. It was built in 1829, and unlike most mosques on the coast it boasts a minaret. Henry Burnier, who was a longtime resident of Shela living in part of what is now Peponi Hotel, supervised and paid for the restoration of the Friday mosque in 1948. The best place from which to view the mosque is on top of the sand dunes where one can get a magnificent sight of Manda island and the Lamu coast in the background with perhaps a glimpse of a dhow sailing gracefully past Shela.

One curious piece of information told by an old man in Shela is that when he was a young boy the people of Shela always removed their sandals before going into Lamu town to show their respect for the people of the older town. Although this is no longer done, the Lamuans still believe that the inhabitants of Shela are “upstarts.”

Opposite Shela on Manda island at a place called Kitau is a block house where several cannons rest undisturbed in the surrounding sand. These cannons were made in Scotland in 1813. The block house was probably built at the same time as the Lamu fort to protect the entrance to Lamu harbour.