The Lighthouse of Mombasa

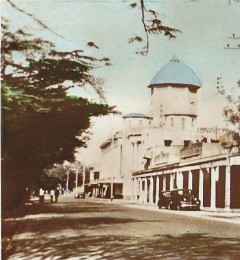

Mombasa 1952

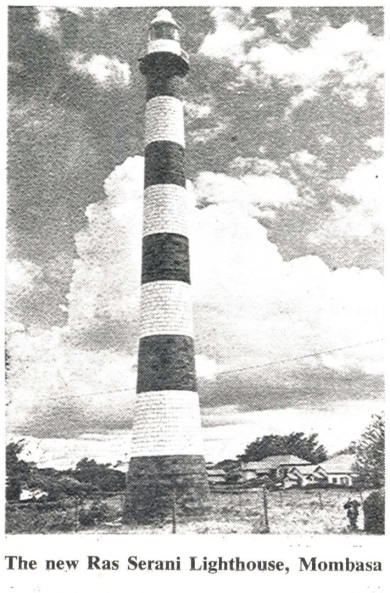

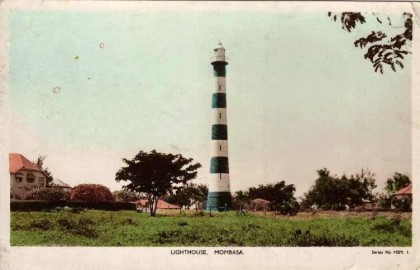

Much local interest was evinced in the Ras Serani high light, the only major lighthouse on the British East African coast, which cast its 21-mile beam across the Indian Ocean for the first time on 24th July. At the top of its 108-ft. high tower a one-second flash every five seconds provides the latest navigational aid to ships, helping them to keep on course in the variable currents of the waters off Mombasa. The tower, which was built by the Administration, is of pre-cast concrete blocks.

Click on Photo

Lighthouses of Kenya

|

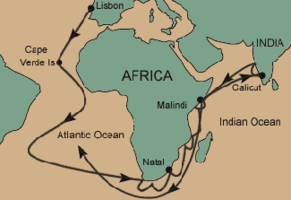

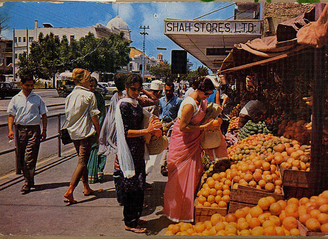

Kenya is a nation on the equatorial east coast of Africa. Although the Portuguese were the first European colonists in Kenya, the country became a British colony from 1890 and remained under British control until it became independent in 1963. Of the East African nations, it has the shortest coastline and is in general the least maritime. However, the coastal city of Mombasa is a major seaport. |

The Kilifi Light

The Kilifi light is a metal tower on a concrete plinth and is comparatively easy to service. But, some years ago, this light and a similar one at Malindi were frequently being extinguished. The reason was that bees were nesting in the metal spinnings which form the hood, or lid, of the lanterns. A minor modification to the hood cured the trouble and the lights have given unbroken service ever since.

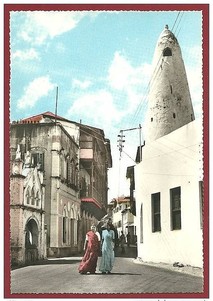

The Malkia sailed on to Malindi and came to anchor in the Bay. The lighthouse there is situated on the hill behind the Vasco da Gama pillar and roughly in the position where it is thought the Portuguese maintained a beacon during their occupation during the 17th and 18th centuries, a time when there was a continual coming and going of men o’ war and merchant vessels. The Malindi light is mounted on a 44 - foot metal tower, the cylinder housing being at ground level, the whole surrounded by a strong iron fence.

Mr. Dev Raj, charge hand of navigational lights, climbed the beacon, checked the mechanism, supervised the extraction of the old cylinders and fitting of replacements. For fifteen years Mr. Dev Raj has worked with the coastal lights; he knows the idio- syncracies of each of them. It is his job to keep them flashing year in and out; to see they maintain a correct gas pressure in order that the dissolved acetylene in each cylinder be released at the correct rate to keep the light at work for the prescribed time.

The Pillar Reef Beacon at Malindi is situated in the reef swell where the water is rarely calm. The cylinders were taken off Malkia in a dinghy equipped with an outboard; taken to the lee side of the beacon and then raised by hoist to the cylinder chamber some twenty feet above sea level. This beacon marks the edge of the reef guarding Malindi Bay and shows a red sector over the reef itself, giving a danger signal to approaching vessels, in common with most other lights this one is fitted with a sunvalve that switches on the light at dusk and extinguishes it at dawn.

THE NORTHERN LIGHTS . . .

being the story of the East African Railways and Harbours Administration's lightship staff on a servicing cruise north of Mombasa, aboard the pilot launch MALKIA, as related by Capt. H.T.V. Church Harbour Master, Mombasa to Edward Rodwell.

WHEN, down at Kilindini Harbour, men talk of The Northern Lights; they are not referring to the Aurora Borealis, but to the navigational lights maintained by the Railways and Harbours Administration on the Coast, north of Mombasa. There are six of these lights, of which five are unattended stations fitted with the Aga system of lighting using dissolved acetylene gas, while the sixth, at Kipini, is an oil burning light needing daily attention.

Serviced Once a Year

The unattended lights are serviced once a year, although a safety margin is allowed which would keep the lighthouses going for a further two or three months. There is one light at the mouth of the Mtwapa river ten miles north of Mombasa. This is serviced by lorry. The remaining four lights are reached by sea, and usually the operation occurs during November between the change of monsoons. At this time, weather is propitious and usually seas are calm. These conditions are necessary, for in rough weather the work could be dangerous. It is no fun transferring a 250 lb. gas cylinder by small boat to the reef beacon at Malindi, or landing cylinders on Shelia Beach, through pounding seas.

This year the task was unavoidably delayed until the first week in March. But the northeast monsoon, the kaskasi, was kind. When the pilot launch Malkia sailed from Mombasa with a crew from the Administration’s lightship staff, and with cylinders and other necessary gear, the sky was almost cloudless. There was only the usual fair-weather swell on the Indian Ocean. It looked as though the five-day job would be just routine.

The first stop was Kilifi, where the lighthouse stands on a bluff, a mile to the north..

of the harbour entrance. The light, established on the present site in 1930, is purely a coastal light. It was not designed to mark the entrance to Kilifi river, which is approached on leading marks from the southeast. The harbour is rarely used nowadays, except by coasters and dhows and occasionally by H.M.S. Rosalind of the Royal East African Navy.

The Kilifi Light

The Kilifi light is a metal tower on a concrete plinth and is comparatively easy to service. But, some years ago, this light and a similar one at Malindi were frequently being extinguished. The reason was that bees were nesting in the metal spinnings which form the hood, or lid, of the lanterns. A minor modification to the hood cured the trouble and the lights have given unbroken service ever since.

The Malkia sailed on to Malindi and came to anchor in the Bay. The lighthouse there is situated on the hill behind the Vasco da Gama pillar and roughly in the position where it is thought the Portuguese maintained a beacon during their occupation during the 17th and 18th centuries, a time when there was a continual coming and going of men o’ war and merchant vessels. The Malindi light is mounted on a 44 - foot metal tower, the cylinder housing being at ground level, the whole surrounded by a strong iron fence.

Mr. Dev Raj, charge hand of navigational lights, climbed the beacon, checked the mechanism, supervised the extraction of the old cylinders and fitting of replacements. For fifteen years Mr. Dev Raj has worked with the coastal lights; he knows the idio- syncracies of each of them. It is his job to keep them flashing year in and out; to see they maintain a correct gas pressure in order that the dissolved acetylene in each cylinder be released at the correct rate to keep the light at work for the prescribed time.

The Pillar Reef Beacon at Malindi is situated in the reef swell where the water is rarely calm. The cylinders were taken off Malkia in a dinghy equipped with an out¬board; taken to the lee side of the beacon and then raised by hoist to the cylinder chamber some twenty feet above sea level. This beacon marks the edge of the reef guarding Malindi Bay and shows a red sector over the reef itself, giving a danger signal to approach¬ing vessels, in common with most other lights this one is fitted with a sunvalve that switches on the light at dusk and extinguishes it at dawn.

The Malkia points Northwards

That job done, Malkia pointed northwards again, crossing Formosa Bay and passing

the light at Kipini at the mouth of the Tana River where the harbourage caters almost exclusively for dhow and fishing traffic. This light provides a problem. Every few years the Tana River changes course and a new lighthouse has to be built. The present one—the third in twelve years—is oil burning, and looked after by the boma staff. It is a simple beacon, constructed of locally made mud bricks and plaster and built in the full knowledge that in a few years’ time it will be in the wrong place.

Sand is a major Problem

The next stop was at the Sheila Light at Lamu. The beacon is at the top of a 170 foot hill. The beach upon which the cylinders are landed, was the scene of a historic battle between Manda and Patta islanders, and even today the wind will so shift the sand as to uncover or cover up again the bones of those slain in the battle or who were drowned whilst trying to escape. The fine sand has itself caused a major problem in the matter of maintaining the full visibility of the Shelia Light, since the sand-laden wind swirls round the lighthouse. At one time it was found that after a few years the outer glazing of the lantern was very efficiently sand-blasted and opaque. Experiments conducted by the the staff of the Navigational light-shop at Mombasa produced a form of steel deflector which was fitted immediately below the lantern, a modification that has proved completely successful, for the light has since maintained its full power.

The cylinders for Shelia Point light, before being rowed ashore in the dinghy, were fitted into fibre bags which serve as a protection as they are dragged over the beach and up the slopes to the light.

When the new cylinders were fitted and the expended ones rolled down to the beach, the charge hand checked the sun valve, and the task was over. For another year the Northern Lights were equipped to send their beams to sea, warning and helping the navigators of deep sea ships and coastal craft as they passed in the night. Down below Malkia rode at anchor. Mr. Dev Raj and his crew were soon aboard; the launch turned her bows southwards . . . Always the Interesting and Unexpected

There is always something interesting and unexpected to be encountered in the maintenance of unwatched lighthouses, be it the recovery of a few pounds of wild honey and beeswax from the hood of a lantern; the finding of a six-foot snake, happily dead, in another hood, or simply the depredations of baboons or the risk of an encounter with leopard or even lion, at Chale Point.

Captain H. T. V. Church, Harbour Master, Kilindini, is proud of his Northern Lights and the light-shop staff. With five years of Trinity House experience on the Coast of Great Britain, he is imbued with the unwritten motto of the lighthouse service; come what may ‘the light must not fail.’ On the East Coast of Africa as on the shores of the British Isles, the lights always serve.

State of the Coast Report

Towards Integrated Management of Coastal and Marine Resources in Kenya

http://www.dlist-asclme.org/sites/default/files/doclib/State%20of%20the%20Coast%20Report-NEMA.pdf