Mackinnon Road Station/Mosque

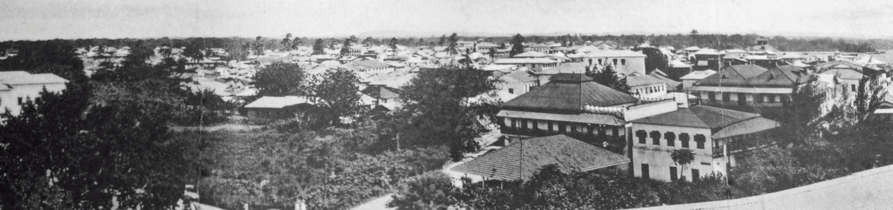

Mackinnon Road is a town in Coast Province, Kenya, with a population of around 8000 in 1999, located between

Mombasa and Voi.

It has a station on the railway between Mombasa and Nairobi and was probably named because it was a junction of the Uganda Railway and the Mackinnon ox cart road 90km/60 miles outside Mombasa. Construction of the road was started in 1890 by

the British East Africa Company and the railway in 1896 by the British colonial administration. The road fell into disuse as the railway overtook it.

There is a mosque which houses the tomb of Seyyid Baghali, a Punjabi foreman at the time of the

building of the railway who was renowned for his strength. Originally there was a simple grave at the site, but after travellers attributed their safe journeys to visiting the grave, a mosque was

built.

At nearly all the stations there have been Englishmen. On the line at Stony Athy was a jackal that lopped off the line as

we approached, and another near Athy River. All along the line were animals and beautiful birds.

Our train is filled with coolies, who carry their beds, as they walk, on their heads. Two trucks are filled with these beds. I intend bringing two home with me; they are made of temon wood, and have

criss-crossed hemp to lie on. They are the same as the beds in the Bible—•“ Take up thy bed and walk."

Mackinnon Road Town : The Legend of Sayeed Bagh Ali Shah

Why Trains SLOW DOWN At Mackinnon Road (We came in Dhows) By Cynthia Salvadori

From interviews with late Ikram Hassan, Mombasa

Yes, it is true. Many people stop at the mosque at Mackinnon Road, and even the through trains and

buses slow down, or at least they used to. It is because a holy man known as Seyyid Baghali is buried there. But that was not his real name. A lot of strange things have been related and written

about him. I will tell you the true story. It was told to me by the father of M. Akbar Shah (whose letter, with a slightly different version, I enclose) and was later confirmed to me by the man’s

sister.

My family, like his, comes from one of the group of three villages near Lahorethat are composed mostly of Seyyids. We are all descended from descendants of the

Prophet who came through Iraq and Persia to teach Islam. When Genghis Khan devastated Persia my ancestors packed up and left and came down to Multan, then moved on to the Punjab and Central India. My

family is from the village of Moin-ud-deen-pur, someone and a half miles from Gujrat. The other two Seyyid villages are very close by. There are about 30-40,000 people in the three villages and we

all know of each other. I am in fact distantly related to ‘Seyyid Baghali’, for my father's sister was married into his family.

As Punjabis were known as good fighters and tough people, the British first recruited Punjabis into their army in India, and then they set up recruitment station to get more Punjabis to build the

railway in Kenya. Our people were happy to volunteer since they got double pay plus transport and rations. Two of my maternal uncles, Sardar Shah and Hakim Shah, came to work on the railway in the

early 1890s. They returned home with money and good reports, saying that despite the dangerous animals they had lived well and ate well. So my father decided to come, in 1906 [see “A Real

Aristocrat”]. And so had the man known as ‘Seyyid Baghali’.

Seyyid Baghali’s real name was Seyyid Fateh Shah. He came from my village, one of three sons of a family of farmers. He was a very strong and hefty young man and so strong that he would carry great

weights lifted over his head, not resting on his head. He was married and had a small child. One evening Fateh Shah came in from the fields very tired and, in front of his wife, his father-in-law

[more likely his father, I think] rebuked him for something.

The next morning Fateh Shah went into town. He saw the recruiting station with a crowd around. His friends encouraged him to sign up. He went home and hardly ate. Next day he disappeared. Word got

back that he had joined the railway, but nothing more was heard of him. When my father came in 1906, he was asked by Fateh Shah’s family to try to locate him. My father could not trace anyone of that

name. It was later that the truth become clear.

In the meantime a legend had grown up about someone called Seyyid Baghali a Punjabi Muslim who was

tremendously strong. It was often said that he was seen walking with his laden karai floating over-not resting upon-his head. Because he was a Seyyid as being very strong was a Seyyid and he been

made a foreman. He died on the railway, along with two other people when trolley they were riding on got out of control. Seyyid Baghali was buried there where he was killed. The grave was made by a

European in charge, who had great respect for Baghali. Every year a cloth was put on the grave

In 1941 I was stationed in the Taru, at Mackinnon Road, where I was cutting timber. I was there for 3years with 500 under me. One of the local guides his old father, named Magado told us stories

about a very strong Indian. He said he had seen it with his own eyes ( the locals used to hide in the woods and watched the Indians work-they themselves did not work because for Africans carrying

loads was for women, not men.) Magado recalled seeing a chap carrying a laden karai, holding it over, not resting it upon, his head. This was the man called Seyyid Baghali, he was obviously the

missing Fateh Shah. He obviously had signed up under a false name, fearing that the news would get to his family before he was able to leave.

In the 1940s when I went there the grave was still a simple one surrounded by bush. Some people would stop there, for they knew it was the grave of a Seyyid and thus of a ‘holy man’. They — not only Muslims but Hindus and especially Sikhs would stop at the grave and ask boons there. People would say when they arrived safely at their destination that it was because they had stopped at the Seyyid’s grave. And so his reputation grew, and the legend started.

It was Mohammed Fazel, a Kashmiri from Jhelum, who was a cattle trader under my father, who started building up the tomb. Then a Luhar from Mombasa, one Hashem| (whom I knew), used to go up to Mackinnon Road and look after the grave. The grave now run by a barber from Navsari called Ahmed Shah who is posing as a Seyyid, he makes much money.

After Ikram had told me what he knew of Fateh Shah, he said he would write to a friend in Pakistan to get more information. The following is the letter he got in response.

Letter Concerning The Pir Of Mackinnon Road

My dear Ikram — Asslamu Ilaqum

[Thank your for] Your kind letter dated 18/6 to hand. I am enclosing here my information about Uncle Fateh Shah along with our Shagra [family tree] which will show you his relationship with us all.

My father Syed Ali Mohammed Shah was the real cousin of Syed Fateh Shah. Fateh Shah and his two real brothers Syed Ishaqu Shah and Syed Said Mian Shah were the sons of

Syed Alam Shah. (He was the grandson of Syed Akbar Shah Sahib, a well-known Saint of Gujrat District who had performed Seven Haj on foot [as was done] in those days and whose grave is in the

village ‘Malkah’ in Gujrat District.)

Syed Alam Shah was also a virtuous man. He was basically a farmer and his eldest

son Fateh Shah was a source of great help to him. From his very birth Fateh Shah, as per his family traditions, was courageous and strictly followed Islamic orders and never deviated from them from

his very childhood. He married and had a son Rasul Shah (who died about ten years back). He was very strong and also a fast runner. He was so fast that he could easily catch a peacock or a vulture

before they were able to fly away.

Once he caught a running cat that had devoured his cockerel. Alam Shah went into litigation with some people in the city of Gujrat over a piece of land. The case went on for about 12 years and it

shattered the financial position of Alam Shah. Fateh Shah, seeing his father in trouble, made up his mind to recruit himself in the Railway department for its project in Africa. In early 1890 he

signed up, together with Sardar Shah and Hakim Shah [maternal uncles of Ikram Hassan], Mohammed Din Awan and others of the village of Moinduddinpur. His parents, brothers and an elder sister Nur

Begum tried their level best to stop him but he was firm in his decision and he left for Africa.

He was, as I said, very strong, for he could easily run fast carrying three maunds over [over, not on] his head. People looking at him with such a load many times

imagined that the load carried by him was actually flying some two or three feet above his head. This phenomenon was also witnessed by his fellow workers in Africa when Fateh Shah used to carry heavy

stones for the Railway tracks.

Even English people, his officers, had noted this feature many times and this [increased his reputation] for spiritual values and piety. He never told a lie, and never touched ‘haram’ food. He was

generous, always helpful to needy and weak people, and he never failed in the observance of the tenets of Islam.

May God bless his Soul.

Affectionately, M. Akbar Shah

(Moinuddinpur, Gujrat)

Sayyed Pir Baghali Shah

The building of the Kenya-Uganda railway brought many Indians to East Africa to work as labourers, clerks and artisans. Many stories are told about the early Indian settlements and about their long journeys on stormy seas before they reached the East African coast.

Many stories are also told about the initial efforts of pioneer Indian individuals and families as they established themselves, worked on building the railway and started new trade links.

Among these stories is a widely popular tale of an Indian labourer named Pir Baghali. He was a wise old man with spiritual powers. People say that while Pir Baghali worked, the kerai or vessel for carrying concrete and sand always remained a few inches above his turbaned head. He was also known to speak and understand the language of animals.

On one occasion, when the working party was aiound the area of Mackinnon, where the labourers had camped and were clearing the bush, a huge python appeared. It had stretched its fangs and was ready to strike at anyone who dared to approach it. Some of the labourers were ready with their lathis or sticks, while one of the Englishmen raised his gun to shoot.

Pir Baghali begged them not to harm the animal. Instead, he asked them to step aside while he knelt down and prayed. He then faced the snake and pleaded, requesting it to leave in peace. The snake stood for a while, poised to attack, but after a while, it gradually backed down and slithered away. Pir Baghali’s power of prayer, it is said, also kept the lions away and the labourers in his camp remained safe. When he died, he was buried next to the railway line in Mackinnon in Kenya, and a monument has been built there in his memory.

Today, many travellers on the Mombasa-Nairobi road visit the monument to pay their respects to Pir Baghali, and they say that the train normally slows down and whistles as it passes near Pir Baghali’s monument.

From the Book: Oral Literature of the Asians in East Africa by Mubina Hassanali and Sanaullah Kirmani Kurtz on Kirmani and Kirmani, 'Oral Literature of the Asians in East Africa'

Oral Literature of the Asians in East Africa (Oral Literature Titles)

http://www.amazon.com/Oral-Literature-Asians-Africa-Titles/dp/9966250859

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/9966250859

Placing Punjabi Muslims on the

frontier of Kenyan

http://www.the-star.co.ke/news/article-74650/placing-punjabi-muslims-frontier-kenyan-history

The Mystic of Mackinnon Road

By Sonya Kassam

Pleasant Surprise At Makindu Gurudwara

KENYA: Many will be aware that there is a large Sikh population in Kenya for many decades. However, very few would have fortunate enough to visit the beautiful Gurudwara in Makindu. This Sikh temple is situated about 100 miles from the Kenyan capital Nairobi, and is known as the main resting point along the isolated long road from Nairobi to Mombasa.

http://www.sikh247.com/world/video-pleasant-surprise-at-makindu-gurudwara/